Free Dacians: Difference between revisions

edit some parts-see talk page Tag: references removed |

Reverted good faith edits by 79.116.211.230 (talk); Bad spelling, broken links, blanking not a good mixture make. Reverting.. (TW) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The term is usually associated with the traditional historical paradigm explaining the origin of the Romanian nation. |

The term is usually associated with the traditional historical paradigm explaining the origin of the Romanian nation. |

||

A substantial population of ethnic-Dacians probably existed on the fringes of the Roman province, especially in the eastern [[Carpathian]] mountains, at least until ca. AD 340. They were probably responsible for a series of incursions into Roman Dacia in the period 120-272, and into the Roman empire South of the river [[Danube]] after Dacia was abandoned by the Romans in 275. However, |

A substantial population of ethnic-Dacians probably existed on the fringes of the Roman province, especially in the eastern [[Carpathian]] mountains, at least until ca. AD 340. They were probably responsible for a series of incursions into Roman Dacia in the period 120-272, and into the Roman empire South of the river [[Danube]] after Dacia was abandoned by the Romans in 275. However, it is unlikely that the [[Costoboci]] and the [[Carpi (people)|Carpi]], two tribes attested as inhabiting E. [[Moldavia]], were ethnic-Dacian. |

||

The Free Dacians disappear from extant recorded history after the 4th century. |

|||

== Traditional paradigm == |

== Traditional paradigm == |

||

| Line 18: | Line 20: | ||

There is substantial evidence that large numbers of ethnic-Dacians continued to exist on the fringes of the Roman province: |

There is substantial evidence that large numbers of ethnic-Dacians continued to exist on the fringes of the Roman province: |

||

(1) During Trajan's Dacian Wars, |

(1) During Trajan's Dacian Wars, enormous numbers of Dacians were killed or led away into slavery. But it also appears that many indigenous Dacians were expelled from the occupied zone, or emigrated of their own accord. Two panels of [[Trajan's Column]] depict lines of Dacian peasants leaving with their families and animals, at the end of each war (102 and 106).<ref name="Trajan's Column">Trajan's Column panels LXXVI and CLV</ref> |

||

(2) In addition, it appears that the Romans did not permanently occupy the whole of Decebal's kingdom. The latter's borders, many scholars believe, are described in Ptolemy's ''Geographia'': the rivers Siret in the East, [[Danube]] in the South, ''Thibiscum'' ([[Timiş]]) in the West and the northern Carpathian mountains in the North.<ref>Ptolemy III.8.1</ref> But the eastern border of the Roman province was by AD 120 set at the ''[[Limes Transalutanus]]'' ("Trans-Olt Frontier"), a line somewhat to the East of the river ''Aluta'' ([[Olt River|Olt]]), thus excluding the Wallachian plain between the ''limes'' and the river Siret |

(2) In addition, it appears that the Romans did not permanently occupy the whole of Decebal's kingdom. The latter's borders, many scholars believe, are described in Ptolemy's ''Geographia'': the rivers Siret in the East, [[Danube]] in the South, ''Thibiscum'' ([[Timiş]]) in the West and the northern Carpathian mountains in the North.<ref>Ptolemy III.8.1</ref> But the eastern border of the Roman province was by AD 120 set at the ''[[Limes Transalutanus]]'' ("Trans-Olt Frontier"), a line somewhat to the East of the river ''Aluta'' ([[Olt River|Olt]]), thus excluding the Wallachian plain between the ''limes'' and the river Siret. In Transylvania, the line of Roman border-forts seems to indicate that the eastern and northern Carpathian Mountains were outside the Roman province, at least partially.<ref name="Barrington Map 22">Barrington Map 22</ref> |

||

Not all the unoccupied areas were necessarily inhabited predominantly by ethnic-Dacians: according to Ptolemy, the northernmost slice of the kingdom (N. Carpathians/[[Bukovina]]) was largely occupied |

Not all the unoccupied areas were necessarily inhabited predominantly by ethnic-Dacians: according to Ptolemy, the northernmost slice of the kingdom (N. Carpathians/[[Bukovina]]) was largely occupied by non-Dacian tribes: the [[Anartes]] and the [[Taurisci]] (probably Celtic) and the Costoboci (probably Sarmatian).<ref>Ptolemy III.8.3</ref> The eastern Wallachian plain was dominated by the [[Roxolani]] Sarmatian tribe.<ref name="Barrington Map 22"/> The area was also shared by a wide diversity of peoples, including the Celto-Germanic [[Bastarnae]] and the Carpi.<ref>Batty (2008)</ref> This does not preclude a continued presence of indigenous [[Geto-Dacians]], possibly subject to [[Roxolani]] overlords. In the same way that in the [[Hungarian Plain]], the Roxolani's Sarmatian cousins, the [[Iazyges]], are recorded by Ammianus as ruling over a serf-population called the [[Limigantes]], who were probably an indigenous [[Dacian]] people (see the name of their ruler, [[Ziais]], a [[Dacian]] name){{Citation needed|date=December 2010}} and who revolted against them forcing the [[Sarmatians]] to seek refugee in Roman empire.<ref>Ammianus</ref> |

||

But there is a lack of data on the inhabitants of the remaining unoccupied region of [[Decebal]]'s kingdom, that between the Transylvanian border of the Roman province and the Siret, i.e. the eastern [[Carpathians]], and it is therefore in these mountain valleys and foothills that the truly "Free" Dacians (in the sense of politically independent) were most likely concentrated, and presumably where most of the refugees from the Roman conquest went.{{Citation needed|date=December 2010}} |

But there is a lack of data on the inhabitants of the remaining unoccupied region of [[Decebal]]'s kingdom, that between the Transylvanian border of the Roman province and the Siret, i.e. the eastern [[Carpathians]], and it is therefore in these mountain valleys and foothills that the truly "Free" Dacians (in the sense of politically independent) were most likely concentrated, and presumably where most of the refugees from the Roman conquest went.{{Citation needed|date=December 2010}} |

||

| Line 32: | Line 34: | ||

Thus, the traditional paradigm's claim of the existence of a substantial Free Dacian population during the Roman era is supported by substantial evidence. |

Thus, the traditional paradigm's claim of the existence of a substantial Free Dacian population during the Roman era is supported by substantial evidence. |

||

However, the identification of the Costoboci and Carpi as ethnic-Dacian is far from secure.<ref name="Batty 2008 378">Batty (2008) 378</ref><ref>cf. Bichir (1976) 146</ref> Unlike the Dacians proper, neither group is attested in Moldavia before Ptolemy (i.e. before ca. 140).<ref>Smith's ''Carpi''</ref> The Costoboci are classified as a [[Sarmatian]] tribe by [[Pliny the Elder]], who locates them as residing around the river ''[[Tanais]]'' (southern river Don) in ca. AD 60, in the Sarmatian heartland of the southern Russia region, far to the East of Moldavia.<ref>Pliny VI.7</ref> [[Ammianus Marcellinus]], writing in ca. 390, also lists the ''gentes Costobocae'' ("Costobocan tribes") among other Sarmatian groups ([[Alans]], etc.) also in central Sarmatia.<ref>Ammianus XXII.8.42</ref> The ethno-linguistic affiliation of the Carpi is uncertain.<ref name="Batty 2008 378"/> In addition to Dacian, it has been variously suggested that they were a Sarmatian, [[Germanic peoples|Germanic]] or even [[Proto-Slavic]] group.<ref>cf. Bichir 146</ref> The contemporaneous existence, alongside ''Dacicus Maximus'', of the victory-title ''Carpicus Maximus'' - claimed by the emperors [[Philip the Arab]] (247),<ref>Sear 2581</ref> Aurelian (273),<ref name="CIL XIII.8973"/> [[Diocletian]] (297)<ref>AE (1973) 526</ref> and Constantine I (317/8)<ref>CIL VIII.8412</ref> - suggests that the Carpi may have been considered ethnically distinct from the Free Dacians by the Romans. |

|||

However, the identification of the Costoboci and Carpi as ethnic-Dacian is debated by some.<ref name="Batty 2008 378">Batty (2008) 378</ref><ref>cf. Bichir (1976) 146</ref> |

|||

The traditional paradigm is also open to challenge in other respects. There is no evidence that the peoples outside the province were "Romanised" to any greater extent than their non-Dacian neighbours, since the archaeological remains of their putative zone of occupation show no greater Roman influence than do other [[Chernyakhov]] culture sites elsewhere in the northern Pontic region; nor that the Free Dacians gave up their native tongue and became Latin-speakers.<ref>Niculescu online paper</ref> In AD 271-5, when the Roman emperor [[Aurelian]] decided to evacuate [[Dacia (Roman province)|the province of Dacia]], its Roman residents, both urban and rural, are reported by ancient sources to have been deported ''en masse'' to Roman territory South of the Danube (i.e. to the province of [[Moesia Inferior]]).<ref>Eutropius IX.15</ref><ref>Victor</ref> However, these reports have been challenged by modern scholars who argue that many rural |

The traditional paradigm is also open to challenge in other respects. There is no evidence that the peoples outside the province were "Romanised" to any greater extent than their non-Dacian neighbours, since the archaeological remains of their putative zone of occupation show no greater Roman influence than do other [[Chernyakhov]] culture sites elsewhere in the northern Pontic region; nor that the Free Dacians gave up their native tongue and became Latin-speakers.<ref>Niculescu online paper</ref> In AD 271-5, when the Roman emperor [[Aurelian]] decided to evacuate [[Dacia (Roman province)|the province of Dacia]], its Roman residents, both urban and rural, are reported by ancient sources to have been deported ''en masse'' to Roman territory South of the Danube (i.e. to the province of [[Moesia Inferior]]).<ref>Eutropius IX.15</ref><ref>Victor</ref> However, these reports have been challenged by some modern scholars who argue that many rural inhabitants of the Roman province, with few links to the Roman administration or army, probably remained behind.<ref>http://books.google.ro/books?id=xxAm3LYT6XsC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Ioana+oltean+dacian+landscape&source=bl&ots=n--kU2Dzs7&sig=MmuesyAR4ac3CHfth22WMz6kLoE&hl=ro&ei=4dToTN_oK4r2sgb_rryOCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=Ioana%20oltean%20dacian%20landscape&f=false</ref>{{Full}} Even if this was the case, the remaining Latin-speakers cannot have exceeded about half of the province's estimated 700,000 inhabitants in 275, since all the troops and their dependents, most of the townspeople and all slaves are certain to have been evacuated.{{Citation needed|date=December 2010}} This would have left few to form a viable nucleus for Daco-Roman continuity, given the number and scale of barbarian invasions in succeeding centuries. |

||

== Ultimate fate == |

== Ultimate fate == |

||

Revision as of 09:17, 26 December 2010

The so-called "Free Dacians" (Romanian: Dacii liberi) is the name given by Romanian historians (but not by ancient sources) to those ethnic-Dacians who putatively remained outside (or emigrated from) the part of the ancient region of Dacia annexed by the Roman empire after the emperor Trajan's Dacian wars of AD 101-6. Contemporary Roman sources refer to "neighbouring Dacians" (Dakai limitrophai) who resided outside Dacia nostra ("Our Dacia") i.e the Roman province of Dacia

The term is usually associated with the traditional historical paradigm explaining the origin of the Romanian nation.

A substantial population of ethnic-Dacians probably existed on the fringes of the Roman province, especially in the eastern Carpathian mountains, at least until ca. AD 340. They were probably responsible for a series of incursions into Roman Dacia in the period 120-272, and into the Roman empire South of the river Danube after Dacia was abandoned by the Romans in 275. However, it is unlikely that the Costoboci and the Carpi, two tribes attested as inhabiting E. Moldavia, were ethnic-Dacian.

The Free Dacians disappear from extant recorded history after the 4th century.

Traditional paradigm

According to the traditional Romanian national-historical paradigm, the "Free Dacians" included both refugees from the Roman conquest who left the Roman-occupied zone and also a number of Dacian-speaking tribes resident outside that zone, notably the Costoboci and the Carpi in Moldavia/Bessarabia. These peoples supposedly absorbed the refugees and constituted the Free Dacians.[1][2]

Through proximity with the Roman province of Dacia, the Free Dacians supposedly became Romanised, adopting the Latin language and Roman culture. Despite this acculturation, the Free Dacians were supposedly irredentists, repeatedly invading the Roman province in an attempt to recover the refugees' ancestral land. They were unsuccessful until the Roman province was abandoned by the emperor Aurelian in AD 275. After this, the Free Dacians "liberated" the Roman province, and joined the Romano-Dacians left behind to form a Latin-speaking Daco-Roman ethnos that was the forebear of the modern Romanian nation.[1]

Validity of paradigm

There is substantial evidence that large numbers of ethnic-Dacians continued to exist on the fringes of the Roman province:

(1) During Trajan's Dacian Wars, enormous numbers of Dacians were killed or led away into slavery. But it also appears that many indigenous Dacians were expelled from the occupied zone, or emigrated of their own accord. Two panels of Trajan's Column depict lines of Dacian peasants leaving with their families and animals, at the end of each war (102 and 106).[3]

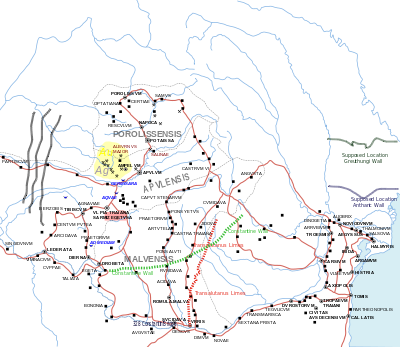

(2) In addition, it appears that the Romans did not permanently occupy the whole of Decebal's kingdom. The latter's borders, many scholars believe, are described in Ptolemy's Geographia: the rivers Siret in the East, Danube in the South, Thibiscum (Timiş) in the West and the northern Carpathian mountains in the North.[4] But the eastern border of the Roman province was by AD 120 set at the Limes Transalutanus ("Trans-Olt Frontier"), a line somewhat to the East of the river Aluta (Olt), thus excluding the Wallachian plain between the limes and the river Siret. In Transylvania, the line of Roman border-forts seems to indicate that the eastern and northern Carpathian Mountains were outside the Roman province, at least partially.[5]

Not all the unoccupied areas were necessarily inhabited predominantly by ethnic-Dacians: according to Ptolemy, the northernmost slice of the kingdom (N. Carpathians/Bukovina) was largely occupied by non-Dacian tribes: the Anartes and the Taurisci (probably Celtic) and the Costoboci (probably Sarmatian).[6] The eastern Wallachian plain was dominated by the Roxolani Sarmatian tribe.[5] The area was also shared by a wide diversity of peoples, including the Celto-Germanic Bastarnae and the Carpi.[7] This does not preclude a continued presence of indigenous Geto-Dacians, possibly subject to Roxolani overlords. In the same way that in the Hungarian Plain, the Roxolani's Sarmatian cousins, the Iazyges, are recorded by Ammianus as ruling over a serf-population called the Limigantes, who were probably an indigenous Dacian people (see the name of their ruler, Ziais, a Dacian name)[citation needed] and who revolted against them forcing the Sarmatians to seek refugee in Roman empire.[8]

But there is a lack of data on the inhabitants of the remaining unoccupied region of Decebal's kingdom, that between the Transylvanian border of the Roman province and the Siret, i.e. the eastern Carpathians, and it is therefore in these mountain valleys and foothills that the truly "Free" Dacians (in the sense of politically independent) were most likely concentrated, and presumably where most of the refugees from the Roman conquest went.[citation needed]

(3) Free Dacians are reported to have invaded and ravaged the province in 214 and 218.[9][10] Several emperors after Trajan, to as late as AD 336, assumed the victory title of Dacicus Maximus ("Totally Victorious over the Dacians"): Antoninus Pius (157),[11] Maximinus I (238),[12] Decius (250)[13] Gallienus (257),[14] Aurelian (272)[15] and Constantine I the Great (336).[16] Since such victory-titles always indicated peoples defeated, not geographical regions, the repeated use of Dacicus Maximus implies the existence of ethnic-Dacians outside the Roman province in sufficient numbers to warrant major military operations into the early 4th century.[17] A grave threat to Roman Dacia through out its history (106-275) is also implied by the permanent deployment of a massive Roman military garrison, of (normally) 2 legions and over 40 auxiliary regiments (ca. 40,000 troops, or 10% of the imperial army's total regular effectives).[18] There is substantial archaeological evidence of major and devastating incursions into Roman Dacia: clusters of coin-hoards and evidence of destruction and abandonment of Roman forts.[19][full citation needed] Since these episodes coincide with occasions when emperors assumed the title Dacicus Maximus, it is reasonable to suppose that the Free Dacians were primarily responsible for these raids.

(4) In 180, the emperor Commodus (r. 180-92) is recorded as having admitted for settlement in the Roman province 12,000 "neighbouring" Daci who had been driven out of their own territory by hostile tribes.[20]

Thus, the traditional paradigm's claim of the existence of a substantial Free Dacian population during the Roman era is supported by substantial evidence.

However, the identification of the Costoboci and Carpi as ethnic-Dacian is far from secure.[21][22] Unlike the Dacians proper, neither group is attested in Moldavia before Ptolemy (i.e. before ca. 140).[23] The Costoboci are classified as a Sarmatian tribe by Pliny the Elder, who locates them as residing around the river Tanais (southern river Don) in ca. AD 60, in the Sarmatian heartland of the southern Russia region, far to the East of Moldavia.[24] Ammianus Marcellinus, writing in ca. 390, also lists the gentes Costobocae ("Costobocan tribes") among other Sarmatian groups (Alans, etc.) also in central Sarmatia.[25] The ethno-linguistic affiliation of the Carpi is uncertain.[21] In addition to Dacian, it has been variously suggested that they were a Sarmatian, Germanic or even Proto-Slavic group.[26] The contemporaneous existence, alongside Dacicus Maximus, of the victory-title Carpicus Maximus - claimed by the emperors Philip the Arab (247),[27] Aurelian (273),[15] Diocletian (297)[28] and Constantine I (317/8)[29] - suggests that the Carpi may have been considered ethnically distinct from the Free Dacians by the Romans.

The traditional paradigm is also open to challenge in other respects. There is no evidence that the peoples outside the province were "Romanised" to any greater extent than their non-Dacian neighbours, since the archaeological remains of their putative zone of occupation show no greater Roman influence than do other Chernyakhov culture sites elsewhere in the northern Pontic region; nor that the Free Dacians gave up their native tongue and became Latin-speakers.[30] In AD 271-5, when the Roman emperor Aurelian decided to evacuate the province of Dacia, its Roman residents, both urban and rural, are reported by ancient sources to have been deported en masse to Roman territory South of the Danube (i.e. to the province of Moesia Inferior).[31][32] However, these reports have been challenged by some modern scholars who argue that many rural inhabitants of the Roman province, with few links to the Roman administration or army, probably remained behind.[33][full citation needed] Even if this was the case, the remaining Latin-speakers cannot have exceeded about half of the province's estimated 700,000 inhabitants in 275, since all the troops and their dependents, most of the townspeople and all slaves are certain to have been evacuated.[citation needed] This would have left few to form a viable nucleus for Daco-Roman continuity, given the number and scale of barbarian invasions in succeeding centuries.

Ultimate fate

The latest secure mention of the Free Dacians in the ancient sources is Constantine I's acclamation as Dacicus Maximus in 336. For the year 381, the Byzantine chronicler Zosimus, records an invasion over the Danube by a barbarian coalition of Huns, Scirii and what he terms Karpodakai ("Carpo-Dacians").[34] There is much controversy about the meaning of this term and whether it refers to the Carpi. However, it certainly refers to the Dacians and, most likely, means the "Dacians of the Carpathians".[35] But it is doubtful whether this term constitutes reliable evidence that the Dacians were still a significant force at this time. Zosimus is widely regarded as a highly untrustworthy chronicler and has been criticised by one scholar as having "an unsurpassable claim to be regarded as the worst of all the extant Greek historians of the Roman Empire...it would be tedious to catalogue all the instances where this historian has falsely transcribed names, not to mention his confusion of events...".[36] On this record, it is quite possible that Karpodakai is either a corruption of a different name or a complete fabrication by Zosimus.

Even if it is accepted that Zosimus' quote proves the continued existence in 381 of "the Dacians" as a distinct ethnic group, it is the last surviving such mention in the ancient sources. The traditional paradigm claims that a Latin-speaking community of Daco-Romans existed throughout the period 400-1200, after which it emerges as the modern Romanian nation in the medieval principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. But it is doubtful whether this view represents the objective historical reality. It is possible that the Dacians simply disappeared as a distinct group, as they mingled with the Germanic and later Slavic migrants that established their hegemony over the Dacian region during the Byzantine period.

Citations

- ^ a b Millar (1970) 279ff.

- ^ Bichir (1976) 172

- ^ Trajan's Column panels LXXVI and CLV

- ^ Ptolemy III.8.1

- ^ a b Barrington Map 22

- ^ Ptolemy III.8.3

- ^ Batty (2008)

- ^ Ammianus

- ^ Hist Aug Caracalla V.4

- ^ Dio LXXIX.24.5

- ^ CIL VIII.20424

- ^ AE (1905) 179

- ^ CIL II.6345

- ^ CIL II.2200

- ^ a b CIL XIII.8973

- ^ CIL VI.40776

- ^ CAH XII 140 (notes 1 and 2)

- ^ Holder (2003) 145

- ^ Bichir (1976)

- ^ Dio LXXIII.3

- ^ a b Batty (2008) 378

- ^ cf. Bichir (1976) 146

- ^ Smith's Carpi

- ^ Pliny VI.7

- ^ Ammianus XXII.8.42

- ^ cf. Bichir 146

- ^ Sear 2581

- ^ AE (1973) 526

- ^ CIL VIII.8412

- ^ Niculescu online paper

- ^ Eutropius IX.15

- ^ Victor

- ^ http://books.google.ro/books?id=xxAm3LYT6XsC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Ioana+oltean+dacian+landscape&source=bl&ots=n--kU2Dzs7&sig=MmuesyAR4ac3CHfth22WMz6kLoE&hl=ro&ei=4dToTN_oK4r2sgb_rryOCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=Ioana%20oltean%20dacian%20landscape&f=false

- ^ Zosimus IV (114)

- ^ Cf. Bichir (1976) 146-8

- ^ Thompson (1982) 446

See also

References

Ancient

- Ammianus Marcellinus Res Gestae (ca. 395)

- Dio Cassius Roman History (ca. AD 230)

- Eusebius of Caesarea Historia Ecclesiae (ca. 320)

- Eutropius Historiae Romanae Breviarium (ca. 360)

- Anonymous Historia Augusta (ca. 400)

- Jordanes Getica (ca. 550)

- Pliny the Elder Naturalis Historia (ca. AD 70)

- Ptolemy Geographia (ca. 140)

- Sextus Aurelius Victor De Caesaribus (361)

- Tacitus Germania (ca. 100)

- Zosimus Historia Nova (ca. 500)

Modern

- AE: Année Epigraphique ("Epigraphic Year" - academic journal)

- Barrington (2000): Atlas of the Greek & Roman World

- Batty, Roger (2008): Rome and the Nomads: the Pontic-Danubian region in Antiquity

- Bichir, Gh. (1976): History and Archaeology of the Carpi from the 2nd to the 4th centuries AD

- Cambridge Ancient History 1st Ed. Vol. XII (1939): The Imperial Crisis and Recovery

- CIL: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum ("Corpus of Latin Inscriptions")

- Holder (Paul) (2003): Auxiliary Deployment in the Reign of Hadrian

- Millar, Fergus (1970): The Roman Empire and its Neighbours

- Niculescu, G-A. : Nationalism and the Representation of Society in Romanian Archaeology (online paper)

- Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1878)

- Thompson, E.A. (1982): Zosimus 6.10.2 and the Letters of Honorius in Classical Quarterly 33 (ii)

External links

is reliable