Cool (aesthetic): Difference between revisions

Futurebird (talk | contribs) →Aristocratic and artistic cool in Europe: we still need sources that say that these are examples of "sprezzatura" |

→African Cool: balancing |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

<blockquote>"Africa and Europe share notions of self-control and imperturbability, expressed under a metaphysical rubric of coolness, viz, notions of sang-froid and coolheadedness"<ref>African Art in Motion, 1979, New York, p. 43</ref></blockquote> |

<blockquote>"Africa and Europe share notions of self-control and imperturbability, expressed under a metaphysical rubric of coolness, viz, notions of sang-froid and coolheadedness"<ref>African Art in Motion, 1979, New York, p. 43</ref></blockquote> |

||

=== |

===Sub-Saharan Cool=== |

||

Author [[Robert Farris Thompson]] has described African American cool as having corollaries in several African cultural traditions, citing the [[Yoruba people|Yoruba]] concept of "Itutu". He cites a definition of cool from the Gola people of [[Liberia]], who define it as the ability to be mentally calm or detached, in an other-wordly fashion, from one's circumstances, to be nonchalant in situations where emotionalism or eagerness would be natural and expected.<ref>Thompson, Robert Farris. "An Aesthetic of the Cool." ''African Arts'', Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1973).</ref> Joseph M. Murphy writes that "cool" is also closely associated with the deity Òsun of the Yoruba religion. <ref>Murphy, Joseph, M. and Sanford, Mei-Mei. ''Òsun Across the Waters: A Yoruba Goddess in Africa and the Americas'', p. 2.</ref> |

Author [[Robert Farris Thompson]] has described African American cool as having corollaries in several African cultural traditions, citing the [[Yoruba people|Yoruba]] concept of "Itutu". He cites a definition of cool from the Gola people of [[Liberia]], who define it as the ability to be mentally calm or detached, in an other-wordly fashion, from one's circumstances, to be nonchalant in situations where emotionalism or eagerness would be natural and expected.<ref>Thompson, Robert Farris. "An Aesthetic of the Cool." ''African Arts'', Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1973).</ref> Joseph M. Murphy writes that "cool" is also closely associated with the deity Òsun of the Yoruba religion. <ref>Murphy, Joseph, M. and Sanford, Mei-Mei. ''Òsun Across the Waters: A Yoruba Goddess in Africa and the Americas'', p. 2.</ref> |

||

Thompson finds the cultural value of cool in Africa and the [[African diaspora]] different from that held by Europeans, who use the term primarily as the ability to remain calm under stress. According to Thompson, there is significant weight, meaning and spirituality attached to cool in traditional African cultures |

Thompson finds the cultural value of cool in Africa and the [[African diaspora]] different from that held by Europeans, who use the term primarily as the ability to remain calm under stress. According to Thompson, there is significant weight, meaning and spirituality attached to cool in traditional African cultures. |

||

"Control, stability, and composure under the African rubric of the cool seem to constitute elements of an all-embracing aesthetic attitude." African cool, writes Thompson, is "more complicated and more variously expressed than Western notions of ''sang-froid'' (literally, "cold blood"), cooling off, or even icy determination." |

"Control, stability, and composure under the African rubric of the cool seem to constitute elements of an all-embracing aesthetic attitude." African cool, writes Thompson, is "more complicated and more variously expressed than Western notions of ''sang-froid'' (literally, "cold blood"), cooling off, or even icy determination."<ref>Thompson, Robert Farris. ''African Arts''.</ref> |

||

<blockquote>The telling point is that the "mask" of coolness is worn not only in time of stress, but also of pleasure, in fields of expressive performance and the dance. Struck by the re-occurrence of this vital notion elsewhere in tropical Africa and in the Black Americas, I have come to term the attitude "an aesthetic of the cool" in the sense of a deeply and completely motivated, consciously artistic, interweaving of elements serious and pleasurable, of responsibility and play.<ref>Thompson, Robert Farris. ''African Arts''.</ref></blockquote> |

|||

===The African American experience=== |

===The African American experience=== |

||

Revision as of 02:33, 5 March 2007

- For other uses of cool, see Cool (disambiguation).

Cool, in popular culture, is an aesthetic of attitude, behavior, comportment, appearance and style. Because of the varied and changing connotations of cool, as well its subjective nature, the word has no one meaning. It has associations of composure and self-control (cf. the OED definition) and is often used as an expression of admiration or approval.

Uses

Cool has been used to describe a general state of well-being, a transcendant, internal peace and serenity. (Thompson, African Arts.) It also can refer to an absence of conflict, a state of harmony and balance as in, "The land is cool," or as in a "cool [spiritual] heart." Such meanings, according to Thompson, are African in origin. Cool is related in this sense to both social control and transcendental balence.[1]

While slang terms are usually comprised of short-lived coinages and figures of speech, cool is an especially ubiquitous slang word, especially among young people. As well as being understood throughout the English-speaking world, the word has even entered the vocabulary of several languages other than English.

Cool can be used to describe composure and absence of excitement in a person, especially in times of stress, and can refer to something that is aesthetically appealing. It is also used to express agreement or assent.

Cool is often used as a general positive epithet or interjection which has a range of related adjectival meanings. Among other things, it can ean calm, stoic, impressive, intriguing, or superlative.

Cool around the world

Nick Southgate writes that, although aesthetic cool has its roots in the Afican-American experience, it is not confined to one particular ethnic group or gender. Sought by product marketing firms, idealized by teenagers, a shield against racial oppression and source of constant cultural innovation, cool has become a global phenomenon that has spread to every corner of the world.[2] According to Dick Pountain and David Robins the slang, use of the word cool has existed for centuries in several cultures.[3] Robert Farris Thompson acknowledges similarities between African and European cool:

"Africa and Europe share notions of self-control and imperturbability, expressed under a metaphysical rubric of coolness, viz, notions of sang-froid and coolheadedness"[4]

Sub-Saharan Cool

Author Robert Farris Thompson has described African American cool as having corollaries in several African cultural traditions, citing the Yoruba concept of "Itutu". He cites a definition of cool from the Gola people of Liberia, who define it as the ability to be mentally calm or detached, in an other-wordly fashion, from one's circumstances, to be nonchalant in situations where emotionalism or eagerness would be natural and expected.[5] Joseph M. Murphy writes that "cool" is also closely associated with the deity Òsun of the Yoruba religion. [6]

Thompson finds the cultural value of cool in Africa and the African diaspora different from that held by Europeans, who use the term primarily as the ability to remain calm under stress. According to Thompson, there is significant weight, meaning and spirituality attached to cool in traditional African cultures.

"Control, stability, and composure under the African rubric of the cool seem to constitute elements of an all-embracing aesthetic attitude." African cool, writes Thompson, is "more complicated and more variously expressed than Western notions of sang-froid (literally, "cold blood"), cooling off, or even icy determination."[7]

The African American experience

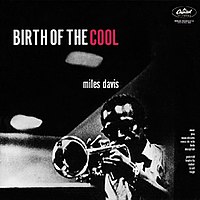

Ronald Perry writes that many words and expressions have passed from African American Vernacular English into Standard English slang including the contemporary meaning of the word "cool."[8] The black jazz scene in the U.S. and among expatriate musicians in Paris, helped popularize notions of cool in the U.S. in the 1940s, giving birth to "Bohemian", or beatnik culture.[2] Shortly thereafter, a style of jazz called cool jazz appeared on the music scene in reaction to bebop, emphasizing a restrained, laid-back solo style.[9]

Marlene Kim Connor connects cool and the post-war African-American experience in her book What is Cool?: Understanding Black Manhood in America. Connor writes that cool is the silent and knowing rejection of racist oppression, a self-dignified expression of masculinity developed by black men denied mainstream expressions of manhood. She writes that mainstream perception of cool is narrow and distorted, with cool often perceived merely as style or arrogance, rather than a way to achieve respect.[10] Similarly, Majors and Billson address what they term “cool pose” in their study and argue that it helps Black men counter stress caused by social oppression, rejection and racism. They also contend that it furnishes the black male with a sense of control, strength, confidence and stability and helps him deal with the closed doors and negative messages of the “generalized other.” They also believe that attaining black manhood is filled with pitfalls of discrimination, negative self-image, guilt, shame and fear. [11]

Designer Christian Lacroix has said that "...the history of cool in America is the history of African-American culture".[12]

In the broader African diaspora

American pop-culture cool

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Aristocratic and artistic cool in Europe

"Aristocratic cool", known as sprezzatura, has existed in Europe for centuries [13]. Raphael’s "Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione" and Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa" are classic examples of sprezzatura[14]. The sprezzatura of the Mona Lisa is seen in both her smile and the positioning of her hands. Both the smile and hands are intended to convey her grandeur, self-confidence and societal position [15]. Sprezzatura involves showing disdain for the mundane work needed to create the air of appearing graceful and courteous.

Sprezzatura can also be applied to the poets of the time, who wanted to make their poetry seem to be the result of careful and meticulous work instead of the product of effortless and spontaneous action and the cultivated ability to "display artful artlessness" [16] French aristocrats have also been described as cool.[17][original research?]

English poet and playwright William Shakespeare used cool in several of his works to describe composure and absence of excitement [18]. In A Midsummer Night's Dream, written sometime in the late-1500s, he contrasts the shaping fantasies of lovers and madmen with "cool reason"[19], in Hamlet he wrote "O gentle son, upon the heat and flame of thy distemper, sprinkle cool patience" [20], and Othello's antagonist Lago is musing about "reason to cool our raging motions, our carnal stings, our unbitted lusts". [21].[original research?]

Asian warrior castes

Template:Sectionstub The ethic of the Samurai caste in Japan, warrior castes in India and East Asia all resemble "cool".Template:Ref harvard. Samurai have been presented as "cool" in modern American movies such as Ghost Dog.[22]

In The Art of War, a Chinese military treatise written during the 6th century BC, Sun Tzu wrote in Chapter XII:

Profiting by their panic, we shall exterminate them completely; this will cool the King's courage and cover us with glory, besides ensuring the success of our mission.

Hispanic machismo

Template:Sectionstub The "machismo" of Hispanic cultures is similar to the modern "cool".Template:Ref harvard

Jewish cool

The status quo of Jewish cool has been the "Jewish funnyman," writes David Marchese in Salon:

- For now, we're mostly stuck with the status quo: Jewish funnymen. A role they've been playing since vaudeville...[23]

Marchese writes on the decline of Jewish cool,

- We've gone from badasses Lou Reed and James Caan to jackasses Adam Sandler and Ben Stiller. Where are the hip male Jews?[24]

The marketing of the "Jewcy" Jew

The interplay between American pop-culture and American Jewish culture may have produced what Hal Niedzviecki calls "Jewish Cool".

I am not only profiling the Jewcy Jew, but also, in many ways, an entire generation of middle-class suburban Jews (such as myself) who spent far more time in the world of pop culture than we did in shul, Hebrew school, and listening to bubby talk about the old days combined.[25]

Niedzviecki criticizes Jewish cool as a creation of diaspora Jewry that is not authentically Jewish in its development, and part of a larger narrative of excessive assimilation by Jews into American popular culture.

"Jewish cool" rejects cosmetic appearence changes such as nose jobs[26] and encourages people to celebrate their ethnic identity rather than feel ashamed of it.[27]

In Turkey

Template:Sectionstub The cool "Anatolian smile" of Turkey is used to mask emotions. A similar "mask" of coolness is worn in both times of stress and pleasure in American and African communities.Template:Ref harvard

Proletariat cool

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Theories of cool

Cool as social distinction

Template:Sectionstub According to this theory, cool is a zero sum game, in which cool exists only in comparison with things considered less cool. Illustrated in the book The Rebel Sell, cool is created out of a need for status and distinction. This creates a situation analogous to an arms race, in which cool is perpetuated by a collective action problem in society.[28]

Cool as an elusive essence

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

According to this theory, cool is a real, but unknowable property. Cool, like "good", is a property that exists, but can only be sought after. [2] In the New Yorker article, "The coolhunt"[3], cool is given 3 characteristics:

- "The act of discovering what's cool is what causes cool to move on"

- "Cool cannot be manufactured, only observed"

- "[Cool] can only be observed by those who are themselves cool".

Cool as a marketing device

[Cool is] a heavily manipulative corporate ethos.

Over the past decade, young black men in American inner cities have been the market most aggressively mined by brandmasters as a source of borrowed "meaning" and identity...The truth is that the "got to be cool" rhetoric of the global brands is, more often than not, an indirect way of saying "got to be black."

— Designer Christian Lacroix[29]

According to this theory, cool can be exploited as a manufactured and empty idea impossed on the culture at large through a top-down process by the "Merchants of Cool"[30]. An artificial cycle of "cooling" and "uncooling" creates false needs in consumers, and stimulates the economy. "Cool has become the central ideology of consumer capitalism".[28] Supporters of this theory avoid the pursuit of cool.

The concept of cool was used in this way to market menthol cigarettes to African Americans in the 1960s. In 2004 over 70% of African American smokers preferred menthol cigarettes, compared with 30% of white smokers. This unique social phenomenon was principally occasioned by the tobacco industry's manipulation of the burgeoning black, urban, segregated, consumer market in cities at that time.[31] According to Fast Company some large companies have started 'outsourcing cool.' They paying other "smaller, more-limber, closer-to-the-ground outsider" companies to help them keep up with customers' rapidly changing tastes and demands.[32]

Cool as an opinion

Quite often, cool is in the eye of the beholder. One person, usually a member of a certain social demographic could consider something to be cool whereas a member of a separate social demographic could consider completely the opposite to be worthy of the label. Trends are usually considered cool when only a small minority are involved in them. More people becoming interested in this trend pushes it towards the mainstream, therefore classifying it as uncool. Something else will then emerge as a new trend, and the cycle will repeat indefinitely.[citation needed]

Cool defined

- "Cool is a knowledge, a way of life."[33] -- Lewis Macadams

- "Cool is an age-specific phenomenon, defined as the central behavioural trait of teenagerhood."[34]

- "Coolness is the proper way you represent yourself to a human being."[35] -- Robert Farris Thompson

See also

References

- ^ An Aesthetic of the Cool Robert Farris Thompson African Arts, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1973), pp. 40-43+64-67+89-91

- ^ a b Coolhunting With Aristotle Welcome to the hunt. by Nick Southgate, Cogent Cite error: The named reference "coolhunt" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Dick Pountain and David Robins, Anatomy of an Attitude, Reaktion Books Ltd., 2000.

- ^ African Art in Motion, 1979, New York, p. 43

- ^ Thompson, Robert Farris. "An Aesthetic of the Cool." African Arts, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1973).

- ^ Murphy, Joseph, M. and Sanford, Mei-Mei. Òsun Across the Waters: A Yoruba Goddess in Africa and the Americas, p. 2.

- ^ Thompson, Robert Farris. African Arts.

- ^ African-American English

- ^ Music of the African Diaspora in the Americas

- ^ Conner, Marlene Kim (1995). What Is Cool? Understanding Black Manhood in America. New York: Crown Publishers. Book profile, Education Resources Information Center [1]. Retrieved on 03-01-2007.

- ^ Boddie, Jacquelyn Lynette. "Exploring the turn-around Phenomenon Experienced by African American Urban Male Adolescents in High School." Retrieved on 02-26-2007.

- ^ Klein (2000) pg. 73-4. The Christian Lacroix quote is from “Off the Street...”, Vogue, April 1994, 337.

- ^ Dick Pountain and David Robins, Cool Rules: Anatomy of an Attitude, Reaktion Books Ltd., 2000.|Pountain and Robins, 2000

- ^ http://www.high.org/uploadedFiles/overview/newsroom/LouvreAtlantaReleaseFINAL(2).pdf

- ^ http://www.loc.gov/catdir/samples/har051/2001024956.html

- ^ http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/castigli.htm

- ^ "The Marshal de Brogho was appointed to command all the troops within the isle of France, a high flying aristocrat, cool and capable of everything." http://www.cooperativeindividualism.org/jefferson_f_05.html

- ^ Dick Pountain and David Robins, Cool Rules: Anatomy of an Attitude, Reaktion Books Ltd., 2000.|Pountain and Robins, 2000

- ^ William Shakespeare: A Midsummer Night's Dream, ACT V, 1. SCENE

- ^ William Shakespeare, The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark, The Harvard Classics, 1909–14. Act III Scene IV

- ^ William Shakespeare: Othello, Act 1

- ^ Way cool way of the samurai, Bruce Kirkland, http://jam.canoe.ca/Movies/Reviews/G/Ghost_Dog/2000/03/10/752999.html

- ^ Cool Jews

- ^ Cool Jews

- ^ From Jew to Jewcy: Has a pop culture phenomenon replaced the need for community?

- ^ Young, Jewish and . . . Cool washingtonpost.com

- ^ FOCUS: Navigating Antisemitic Encounters

- ^ a b Heath, Joseph and Potter, Andrew. The Rebel Sell. Harper Perennial, 2004.

- ^ Klein (2000) pg. 73-4. The Christian Lacroix quote is from “Off the Street...”, Vogue, April 1994, 337.

- ^ "Merchants of Cool"

- ^ The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States Phillip S. Gardiner Dr.P.H

- ^ A Craving For Cool July/August 2006

- ^ "Interview with the Author of Birth of the Cool, Lewis Macadams." SimonSays.com, Simon & Schuster. Retrieved on 02-27-2007.

- ^ Marcel Dansei, Cool: The Signs and Meanings of Adolescence, p. 1

- ^ Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit. New York: Vintage Books, 1983, p. 13.