List of marches by John Philip Sousa: Difference between revisions

ChrisTheDude (talk | contribs) |

→List of marches: Added "!scope=col|" to column headers and caption to table. |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

[[File:Sousa1930RoyalWelshFusiliersPremiere.ogv|thumb|Sousa conducting the band at [[White House]] in 1930|alt=Sousa conducting the band at White House in 1930]] |

[[File:Sousa1930RoyalWelshFusiliersPremiere.ogv|thumb|Sousa conducting the band at [[White House]] in 1930|alt=Sousa conducting the band at White House in 1930]] |

||

{| class="wikitable sortable plainrowheaders" |

{| class="wikitable sortable plainrowheaders" |

||

|+ {{sronly|List of marches}} |

|||

|+ |

|||

!Title |

!scope=col | Title |

||

!Composition year |

!scope=col | Composition year |

||

! class="unsortable" |Notes |

!scope=col class="unsortable" |Notes |

||

! class="unsortable" |Audio |

!scope=col class="unsortable" |Audio |

||

! class="unsortable" | {{abbr|Ref.|References}} |

!scope=col class="unsortable" | {{abbr|Ref.|References}} |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!scope=row |{{sort|Review|"Review"}} |

!scope=row |{{sort|Review|"Review"}} |

||

Revision as of 03:19, 18 June 2021

- For a complete list of compositions by John Philip Sousa, see List of compositions by John Philip Sousa

John Philip Sousa was an American composer and conductor of the late Romantic era known primarily for American military marches.[1] He composed 136 marches,[a] from 1873 until his death in 1932.[2] A few of his marches are derived from his other musical compositions such as melodies and operettas. Some of his most famous marches include "The Stars and Stripes Forever", "Semper Fidelis", "The Washington Post", "The Liberty Bell", and "Hands Across the Sea".[3] A British band journalist named Sousa "The March King", in comparison to "The Waltz King" — Johann Strauss II.[4] However, not all of Sousa's marches had the same public appeal.[2] Some of his early marches are lesser known and rarely performed.[2]

He composed marches for several American universities, including the University of Minnesota,[5] University of Illinois,[6] University of Nebraska,[7] Kansas State University,[8] Marquette University,[9] Pennsylvania Military College (now known as Widener University), and the University of Michigan. He served as leader of the Marine Band from 1880 to 1892, and performed at the inaugural balls of President James A. Garfield and Benjamin Harrison.[10]

"The Stars and Stripes Forever" is the national march of the United States, and "U.S. Field Artillery" is the official march of the U.S. Army. After leaving the Marine Band, he formed a civilian band and made many tours and performances in the subsequent 39 years.[11] He died on March 6, 1932, at the age of 77 leaving his last march, "Library of Congress", unfinished.[12]

List of marches

| Contents |

|---|

| 1873-80 · 1881-90 · 1891-1900 · 1901-10 · 1911-20 · 1921-30 · 1931-32 |

| Title | Composition year | Notes | Audio | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Review" | 1873 | Sousa's Op. 5, "Review" was his first published march and was dedicated to Colonel William G. Moore.[13] | [14] | |

| "Salutation" | 1873 | "Salutation" was composed while Sousa was a musician in the Marine Band; he dedicated it to the new leader Louis Schneider.[15] | [16] | |

| "The Phoenix" | 1875 | This march was dedicated to Milton Nobles. Parts of this march were later used in Sousa's "Manhattan Beach".[17] | [18] | |

| "Revival" | 1876 | This march was composed upon the suggestion of fellow composer Simon Hassle. The hymn "In the Sweet By-and-By" was incorporated into the march.[13] | [19] | |

| "The Honored Dead" | 1876 | The occasion of this march's composition is unknown, but it was arranged upon the death of President Ulysses S. Grant in 1885.[20] | [21] | |

| "Across the Danube" | 1877 | Sousa credits the inspiration for this march to the victory of Christendom over the Turks in 1877.[22] | [23] | |

| "Esprit-de-corps" | 1878 | Esprit de corps is a french term meaning "the spirit of the body". It was published one year after Sousa resigned from the Marine Corps.[24] | [25] | |

| "On the Tramp" | 1879 | This march was based on the song "Out of Work" by Septimus Winner. The title of the march was a slang expression in the 1880's, meaning "on the lookout for employment".[17] | [26] | |

| "Resumption" | 1879 | The title of this march was derived from the resumption of the use of gold and silver coins in the U.S.[13] | [27] | |

| "Globe and Eagle" | 1879 | This march borrows its title from the emblem of the Marine Corps. It was one of several military-related titles chosen by Sousa while he was an orchestra conductor.[28] | [29] | |

| "Our Flirtation" | 1880 | "Our Flirtation" was from a musical comedy produced in 1880. It was dedicated to Henry L. West of The Washington Post.[17] | [30] | |

| "Recognition March" | 1880 | This march was presented by Sousa's heirs to the Library of Congress in 1970. It is considered to be a revised version of Sousa's "Salutation" march.[31] | [32] | |

| "Guide Right" | 1881 | Sousa composed this march for use in parade, dedicating it to R. S. Collum, captain of the Marine Corps.[33] | [34] | |

| "President Garfield's Inauguration" | 1881 | This was one of the two marches Sousa dedicated to U.S. presidents. It was composed for the inauguration of James A. Garfield, and was first performed on March 4, 1881.[35] | [36] | |

| "In Memoriam" | 1881 | This march was composed and dedicated to President James A. Garfield, upon his death. The dirge was played by the Marine Band as the president's body was received in Washington D.C. [20] | [37] | |

| "Right Forward" | 1881 | This march is considered the second version of "Guide Right". It was also dedicated to R. S. Collum.[38] | [39] | |

| "The Wolverine" | 1881 | Sousa composed and dedicated this march to David H. Jerome, Governor of Michigan. It was premiered in March 1881.[40] | [41] | |

| "Yorktown Centennial" | 1881 | Sousa composed this march to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the British surrender at Yorktown, one of the last important battles in the Revolutionary War.[42] | [43] | |

| "Congress Hall" | 1882 | This march was composed after the Marine Band's first visit to the Congress Hall Inn in Cape May, New Jersey. He dedicated it to the proprietors of the inn, H. J. Crump and J. R. Crump.[44] | [45] | |

| "Bonnie Annie Laurie" | 1883 | Sousa composed this march by taking inspiration from an old Scottish ballad "Annie Laurie", which he considered the most beautiful folk song.[46] | [47] | |

| "Mother Goose" | 1883 | This march was composed using various nursery tunes like "Our Dear Doctor", "There Is a Man in Our Town", etc.[48] | [49] | |

| "Pet of the Petticoats" | 1883 | The occasion and reason for this march's composition are unknown.[50] | [51] | |

| "Right-Left" | 1883 | Sousa composed this march in 1883; it is famous for its trio part, which calls for shouts of "Right! Left!" at regular intervals.[38] | [52] | |

| "Transit of Venus" | 1883 | This march was composed for the unveiling of a statue of Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and was premiered in April 1883.[53] | [54] | |

| "The White Plum" | 1884 | Sousa composed this march by transforming a previous piece of which he composed with Edward M. Taber. He rearranged the piece and added new sections.[55] | [56] | |

| "The Mikado" | 1885 | This march was based on themes from the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta of the same name.[57] | [58] | |

| "Mother Hubbard" | 1885 | This march is considered to be a version of "Mother Goose" as it is also based on a nursery rhyme theme.[48] | [59] | |

| "Sound Off" | 1885 | This march was composed and dedicated to Major George Porter Houston. The title of the march is a military command.[60] | [61] | |

| "Triumph of Time" | 1885 | The occasion and reason for this march's composition are unknown.[62] | [63] | |

| "The Gladiator" | 1886 | The inspiration for this march is not confirmed, but it is widely believed that Sousa might have been inspired by a literary account of some particular gladiator. It was initially composed for a music publisher in Pennsylvania, but after they rejected the march, it was sold to Harry Coleman, who sold over a million copies of it.[28] | [64] | |

| "The Rifle Regiment" | 1886 | The occasion for the composition of this march is unknown, but it was dedicated to the officers of the 3rd U.S. Infantry.[13] | [65] | |

| "The Occidental" | 1887 | The occasion of this march's composition is unknown, but it was published four years after its composition.[66] | [67] | |

| "Ben Bolt" | 1888 | Sousa composed this march by incorporating a melody of a song with the same name.[68] | [69] | |

| "The Crusader" | 1888 | This march was composed by Sousa after being "knighted" by Columbia Commandery No. 2, a local division of the Knights Templar of the Masonic York Rite. It is believed that Sousa used fragments of Masonic music in the march.[70] | [71] | |

| "National Fencibles" | 1888 | The titular National Fencibles were a Washington, D.C.-based drill team.[48] | [72] | |

| "Semper Fidelis" | 1888 | During a conversation with Sousa, President Chester A. Arthur expressed his displeasure for "Hail to the Chief", the personal anthem of the president, and requested that Sousa compose a more appropriate piece.[73] "Semper Fidelis" was composed two years after Arthur's death, which takes its title from the motto of the U.S. Marine Corps, which means "always faithful".[74] | [75] | |

| "The Picador" | 1889 | This march was composed in 1889, and was soon sold to publisher Harry Coleman, for $35. A bullfight was depicted on the front page of its sheet music.[50] | [76] | |

| "The Quilting Party March" | 1889 | This march was composed from a famous song named "Aunt Dinah's Quilting Party".[31] | [77] | |

| "The Thunderer" | 1889 | This march was composed on the occasion of the twenty-fourth triennial Conclave of the Grand Encampment of the Knights Templar, and was dedicated to Columbia Commandery No. 2.[78] | [79] | |

| "The Washington Post" | 1889 | This march was composed for the award ceremony of an essay contest organized by The Washington Post. With President Benjamin Harrison in attendance, the march was premiered in June 1889.[80] | [81] | |

| "Corcoran Cadets" | 1890 | Sousa composed this march at the request of the Corcoran Cadets drill team.[44] | [82] | |

| "High School Cadets" | 1890 | This march was composed upon the request of the students of the only high school in Washington, D.C. Sousa was requested to compose a march superior to his "National Fencibles". It was published in February 1890.[83] | [84] | |

| "The Loyal Legion" | 1890 | This march was composed to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Loyal Legion. It was first played in April 1890.[85] | [86] | |

| "Homeward Bound" | 1891-92 | "Homeward Bound" was an unpublished march whose existence was first hinted at in Sousa's autobiography Marching Along. It was not discovered until 1965, 23 years after Sousa's death. It is believed to have been composed in 1891 or 1892.[20] | [87] | |

| "The Belle of Chicago" | 1892 | Sousa composed this march to salute the ladies of Chicago, an action for which he was criticized. The march is more popular overseas than in the United States.[68] | [88] | |

| "March of the Royal Trumpets" | 1892 | This march was never published in its original form. Egyptian trumpets were used in its composition.[89] | [90] | |

| "On Parade" | 1892 | This march was published after being orchestrated into two different Sousa compositions. It was also known as "The Lion Tamer".[91] | [92] | |

| "The Triton" | 1892 | Originally composed by a composer named J. Molloy, this march was formed by transforming Molloy's simple arrangement into a march.[53] | [93] | |

| "The Beau Ideal" | 1893 | An inscription on the original sheet music indicated that "Beau Ideal" was a newly formed organization called The National League of Musicians of United States.[68] | [94] | |

| "The Liberty Bell" | 1893 | Sousa initially composed this march as an operetta at the request of Francis Wilson, but he later transformed it into a march. The unveiling of a painting of theLiberty Bell in Chicago and his son's march in a Philadelphia parade in the bell's honor inspired Sousa to name the march "The Liberty Bell".[95] | [96] | |

| "Manhattan Beach" | 1893 | This march had been derived from an earlier composition, probably "The Phoenix March". It was dedicated to Austin Corbin.[97] | [98] | |

| "The Directorate" | 1894 | This march was composed in appreciation of a honor bestowed upon Sousa by the Board of Directors of the 1893 St. Louis Exposition.[24] | [99] | |

| "King Cotton" | 1895 | This march was composed for the Cotton States and International Exposition of 1895. It was named the official march of the exposition.[100] | [101] | |

| "El Capitan" | 1896 | This march was extracted from Sousa's operetta, El Capitan. It was played at Admiral Dewey's victory parade in New York in 1899.[102] | [103] | |

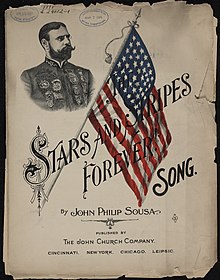

| "The Stars and Stripes Forever" | 1896 | "The Stars and Stripes Forever" is Sousa's most famous composition.[104] He composed the march at sea on Christmas Day in 1896 and committed the notes to paper on his arrival to the United States.[105] It was first performed at Willow Grove Park, just outside Philadelphia, on May 14, 1897, and was immediately greeted with enthusiasm.[106] In 1987, it was made the national march of the United States by an act of Congress.[107] | [108] | |

| "The Bride Elect" | 1897 | This march was extracted from an operetta named The Bride Elect. Frank Simon, a cornetist in Sousa's band, said that it was one of Sousa's favorite marches.[102] | [109] | |

| "The Charlatan" | 1898 | This march is extracted from Acts II and III of Sousa's same-named operetta.[110] | [111] | |

| "Hands Across the Sea" | 1899 | It is believed that Sousa took inspiration for this march from an incident in the Spanish-American War. He did not address it to any particular nation, but to all of America's friends abroad. It was first played at the Philadelphia Academy of Music in April 1899.[112] | [113] | |

| "The Man Behind the Gun" | 1900 | Sousa considered this march to be an echo of the Spanish-American war, and it first appeared as an operetta in 1899.[97] | [114] | |

| "Hail to the Spirit of Liberty" | 1900 | Sousa composed "Hail to the Spirit of Liberty" for his band's first overseas tour of Paris. It was first played when Lafayette's monument was unveiled there on July 4.[33] | [115] | |

| "The Invincible Eagle" | 1901 | This march was dedicated to the Pan-American Exposition, held in Buffalo in 1901.[116] | [117] | |

| "The Pride of Pittsburgh" | 1901 | This march was composed for the dedication of a music hall in Pennsylvania. The title of the march was selected through a contest arranged by a newspaper.[35] | [118] | |

| "Imperial Edward" | 1902 | This march was composed for and dedicated to Edward VII. The trio of this march consists of fragments of "God save the King" [20] | [119] | |

| "Jack Tar" | 1903 | This march was originally titled "British Tar", and it contains traces of "The Sailor's Hornpipe", a traditional melody associated with the British Royal Navy. Premiered at London's Albert Hall in 1903, it differs from other Sousa marches in its unusual structure.[116] | [120] | |

| "The Diplomat" | 1904 | After being impressed by the diplomatic skills of Secretary of State John Hay, Sousa composed this march and dedicated it to him.[121] | [122] | |

| "The Free Lance" | 1906 | This march was extracted from Sousa's operetta of the same name. The trio of the march is based on "On to Victory" from the operetta.[123] | [124] | |

| "Powhatan's Daughter" | 1907 | This march was composed for the 1907 Jamestown exposition, and was a salute to Chief Powhatan's daughter Pocahontas.[35] | [125] | |

| "The Fairest of the Fair" | 1908 | On being invited with his band to play at Boston food fair, Sousa composed this march for the fair. It was first played in September 1908.[126] | [127] | |

| "The Glory of the Yankee Navy" | 1909 | The march was composed for the musical comedy "The Yankee Girl"; Sousa dedicated it to Blanche Ring, the star of the show.[128] | [129] | |

| "The Federal" | 1910 | Sousa composed this march just before embarking on his world tour, honoring the people of Australia and New Zealand. It was originally titled "The Land of the Golden Fleece", but that was changed to "The Federal" upon the suggestion of George Reid, the High Commissioner for Australia.[130] | [131] | |

| "From Maine to Oregon" | 1913 | Sousa's operetta "All American" had been transformed to this march, with many passages, which were repetitive were removed.[123] | [132] | |

| "Columbia's Pride" | 1914 | "Columbia's Pride" was based on a Sousa's 1890 song "Nail the flag to the mast". Sousa made some modifications in the song and composed this march for piano, which he apparently never arranged on a band or orchestra.[133] | [134] | |

| "The Lamb's March" | 1914 | "The Lamb's March" was composed and dedicated to Lams Club of New York. Fragments of this march were later transformed into Sousa's 1882 operetta "The Smugglers".[100] | [135] | |

| "The New York Hippodrome" | 1915 | "The New York Hippodrome" was composed in commemoration of his band's tour as his band was featured in extravaganza at the New York Hippodrome.[136] | [137] | |

| "March of the Pan Americans" | 1915 | "March of the Pan-Americans" is Sousa's longest march, lasting approximately fifteen minutes. The march incorporated national anthems of various nations.[89] | ||

| "The Pathfinder of Panama" | 1915 | "The Pathfinder of Panama" was composed upon the request from Walter Anthony, a San Francisco Call's reporter. It was dedicated to Panama Canal and Panama Pacific exposition held in 1915.[17] | [138] | |

| "America First" | 1916 | President Woodrow Wilson's speech at the twenty-fifth anniversary convention of the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1915 inspired Sousa to compose "America First". It was premiered on February 22, 1916 (George Washington's birthday).[139] | [140] | |

| "Boy Scouts of America" | 1916 | Sousa composed "Boy Scouts of America" upon request of Charles D. Hart, President of Philadelphia scout organization. It was dedicated to the boy scouts of America.[46] | [141] | |

| "Liberty Loan" | 1917 | "Liberty Loan" was composed for Fourth Liberty Loan campaign of World War I, upon joint request from Secretary of Treasury William McAdoo and Liberty Loan Director Charles Schweppe.[85] | [142] | |

| "The Naval Reserve" | 1917 | "The Naval Reserve" was dedicated to officers of the naval reserve. Other titles for this march were "Boys in the navy blue" and "Great lakes".[143] | [144] | |

| U.S. Field Artillery" | 1917 | On being requested by Army Lieutenant George Friedlander of the 306th Field Artillery, Sousa composed "U.S. Field Artillery". It is built around an existing song named The Caisson Song and is the official march of U.S. Army.[145] | [146] | |

| "The White Rose" | 1917 | Sousa composed "The White Rose" upon request of Pennsylvania civic committee. It was played at a public concert by combined bands in 1917.[55] | [147] | |

| "Wisconsin Forward Forward" | 1917 | The occasion and purpose of "Wisconsin Forward Forward" is unknown, although it is speculated that Sousa composed it to salute Wisconsin's contribution into war efforts.[40] It was originally titled "Solid men to front", but that title was crossed out on the march's music manuscript, with the present title written.[40] | [148] | |

| "Anchor and Star" | 1918 | Sousa composed "Anchor and Star" while leading the Navy Battalion Band during World War I. He dedicated it to the U.S. Navy and it was named after the U.S. Navy's emblem.[139] | [149] | |

| "Bullets and Bayonets" | 1918 | Composed during World War I, "Bullets and Bayonets" was dedicated to the officers and men of U.S. infantry [102] | [150] | |

| "The Chantyman's March" | 1918 | Sousa composed "The Chantyman's March" from an article he wrote, entitled "Songs of the sea". It incorporates eight chanteys.[110] | [151] | |

| "Flags of Freedom" | 1918 | "Flags of Freedom" was composed upon the request of Joseph Gannon, chairman of Fourth liberty loan drive in World War I. Belgium, Italy, France, Great Britain and America were represented in this march.[b][130] | [152] | |

| "Sabre and Spurs" | 1918 | "Sabre and Spurs" was dedicated to officers of 311th cavalry and was also known as "March of the American Cavalry".[15] | [153] | |

| "Solid Man to the Front" | 1918 | "Solid Man to the Front" was composed during World War I. The title was initially used in music sheet of "Wisconsin Forward" march, but was later used for this march.[60] | [154] | |

| "USAAC" | 1918 | "USAAC" march was composed for members of the United States Army Ambulance Corps. It contained melodies from a musical called "Good-Bye Bill".[155] | [156] | |

| "The Volunteers" | 1918 | "The Volunteers" was composed upon request of Robert D. Heinl, chief of Defense Department of Patriotic services. It was premiered in March 1918.[157] | [158] | |

| "Wedding March" | 1918 | Sousa composed "Wedding March" upon request from representatives of American relief Legion during World War I.[55] | [159] | |

| "The Victory Chest" | 1918 | "The Victory Chest" was composed in May 1918. The occasion and reason for composition of this march are unknown.[157] | [160] | |

| "The Golden Star" | 1919 | "The Golden Star" was composed in memory of Theodore Roosevelt's son, who was killed in France. The composition was heartily, but seriously received immediately after World War I.[161] | [162] | |

| "Comrades of the Legion" | 1920 | Sousa composed "Comrades of the Legion" shortly after World War I for the newly formed American Legion. It was titled "Comrades of the Legion", but it was changed to "The American Legion March". However, original title was used in the published version.[133] | [163] | |

| "On the Campus" | 1920 | Sousa composed "On the Campus" on request of the publisher and dedicated it to "collegians, past, present, and future".[17] | [164] | |

| "Who's Who In Navy Blue" | 1920 | "Who's Who In Navy Blue" was composed upon request of student body from U.S. Naval Academy. T. R. Wirth suggested title "Ex Scienta Tridens", but Sousa rejected the title and named it "Who's Who in Navy Blue".[55] | [165] | |

| "Keeping in Step With the Union" | 1921 | The inspiration for "Keeping in Step With the Union" came from 1855 speech by Congressman Rufus Choate. The march is dedicated to First lady Florence Harding.[100] | [166] | |

| "The Gallant Seventh" | 1923 | "The Gallant Seventh's" title had been taken from a regiment on New York National Guard. Sousa composed this march upon request from Colonel Wade H. Hayes.[123] | [167] | |

| "The Dauntless Battalion" | 1922 | Upon receiving honorary doctorate from Pennsylvania Military College in Chester, Sousa composed "The Dauntless Battalion" to honor the cadets. It was originally titled "Pennsylvania Military College March", but upon its publication, title was changed to "The Dauntless Battalion"[121] | [168] | |

| "March of the Mitten Men" | 1923 | "March of the Mitten Men" was composed and dedicate to Thomas E. Mitten. For its second edition, the title was changed to "Power and Glory".[89] | [169] | |

| "Nobles of the Mystic Shrine" | 1923 | "Nobles of the Mystic Shrine" was composed on request of Sousa's nephew, and was dedicated to Almas Temple and Imperial council.[136] | [170] | |

| "Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company" | 1924 | Sousa composed "Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company" upon request of Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company. It was formally presented to the company at Symphony hall in Boston, Massachusetts in September, 1924.[139] | [171] | |

| "The Black Horse Troop" | 1924 | Sousa dedicated "The Black Horse Troop" to the mounted troops of a Cleveland National Guard Unit. His admiration of horses is reflected by this march as he considered black horses used in Guard Unit to be his inspiration.[68] | [172] | |

| "Marquette University March" | 1924 | Upon receiving honorary doctorate from Marquette University, "Marquette University March" was composed as an expression of appreciation to the university.[57] | [173] | |

| "The National Game" | 1925 | "The National Game" was composed on request of Kenesaw Landis, baseball's high commissioner, on occasion of National League's fiftieth anniversary.[143] | [174] | |

| "The Gridiron Club" | 1925-26 | Another version of this march composed for piano is also called "Universal Peace", which was discovered among his papers in 1965. Other titles for "The Gridiron Club" are "The Wildcat" and "The Untitled March".[161] | [175] | |

| "The Universal Peace" | 1925-26 | The occasion and reason for "The Universal Peace" composition are unknown. Manuscript of this march was found with Sousa's documents in 1965.[62] | [62] | |

| "Old Ironsides" | 1926 | "Old Ironsides" was composed for a rally held in Madison Square Garden, regarding deterioration of historic old Ironsides. The march was never published.[66] | [176] | |

| "The Pride Of The Wolverines" | 1926 | Sousa composed "The Pride Of The Wolverines" upon request by Detroit's Mayor John W. Smith. It was later declared official march of Detroit.[31] | [177] | |

| "Sesqui-Centennial Exposition March" | 1926 | "Sesqui-Centennial Exposition March" was composed on request of Sesquicentennial Exposition officials, for one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of American independence.[74] | [178] | |

| "The Atlantic City Pageant" | 1927 | Sousa wrote "The Atlantic City Pageant" on suggestion of Atlantic City's mayor Anthony M. Ruffu. It was played to celebrate the second annual engagement of Sousa's band in Atlantic City.[179] | [180] | |

| "Magna Carta" | 1927 | Sousa composed "Magna Carta" as a tribute on International Magna Carta day Association.[97] | [181] | |

| "Minnesota March" | 1927 | "Minnesota March" was composed upon request of University of Minnesota football team. Sousa used Indian themes in this march, and later added field drum and bugle parts.[57] | [182] | |

| "Riders for the Flag" | 1927 | "Riders for the Flag" was composed by the request of Colonel Osmun Latrobe, and was dedicated to him.[13] | [183] | |

| "Golden Jubilee" | 1928 | Sousa composed "Golden Jubilee" to commemorate his fiftieth year as a conductor. Initially he was hesitant to compose anything for his own gratification, but reasoned that his public might expect something.[128] | [184] | |

| "New Mexico" | 1928 | "New Mexico" march was composed upon request of J. F. Zimmerman, President of University of New Mexico. It was original titled "The Queen of the Plateau".[143] | [185] | |

| "Prince Charming" | 1928 | Student band from Elementary school in Los Angeles inspired Sousa to compose "Prince Charming". It was dedicated to band's organizer Jennie L. Jones.[31] | [186] | |

| "University of Nebraska" | 1928 | osed "University Of Nebraska" for University of Nebraska upon its Director's request. He initially considered naming the march "The Corn-huskers", but ended up naming it "University of Nebraska", dedicating it to the faculty and students of the University.[62] | [187] | |

| "University of Illinois" | 1929 | Sousa composed this march for University of Illinois, as he considered its band to be the finest college band. It was premiered in July 1929.[62] | [188] | |

| "La Flor De Sevilla" | 1929 | "La Flor De Sevilla" was inspired from an old Spanish proverb "Quien no ha visto Sevilla no ha visto maravilla" meaning "He, who has not seen Sevilla has not seen beauty". The march was composed at the request of the directors of Ibero-American-exposition held at Sevilla, Spain.[130] | [189] | |

| "Daughter of Texas" | 1929 | "Daughter of Texas" was composed upon submission of a petition signed by 1300 students of Texas college. Two different sets of marched were composed, but one march from the set has been lost.[70] | [190] | |

| "Foshay Tower Washington Memorial" | 1929 | "Foshay Tower Washington Memorial" was composed from parts of "Daughter of Texas", another of Sousa's marches. It was re-premiered in August 1976, when Sousa's name was added to the hall of fame for Great Americans.[123] | [191] | |

| "The Royal Welch Fusiliers" | 1929 | "The Royal Welch Fusiliers" were two marches composed to commemorate the association of U.S. Marines with Battalion of Royal Welch in Britain. It is the only march written by Sousa for a British Army regiment.[192] The two versions have the same title, and are referred as Number 1 and 2.[38] | [193] | |

| 1930 | ||||

| "George Washington Bicentennial March" | 1930 | Sousa was requested to compose a march to commemorate two hundredth anniversary of George Washington. Sousa participated and arranged "George Washington Bicentennial March" in the final ceremony, conducting combined bands of Navy, Army and Marine Corps.[194] | [195] | |

| "Harmonica Wizard" | 1930 | Sousa had composed "Harmonica Wizard" when he was leading the "hoxie's boys" harmonica band. It was first performed in November 1930.[83] | [196] | |

| "The Legionnaires" | 1930 | "The Legionnaires" was composed on request of French government for the 1931 International Colonial and Overseas Exposition in Paris.[95] | [197] | |

| "The Salvation Army" | 1930 | "The Salvation Army" was composed on request of Commander Evangeline Booth of Salvation Army. It was premiered in New York on fiftieth anniversary of Salvation Army.[15] | [198] | |

| "The Wildcats" | 1930/31 | Parts of "The Wildcats" was composed in early 1926. It was originally composed for Kansas State College, but the college was provided completely different march.[40] | [40] | |

| "The Aviators" | 1931 | Sousa dedicated "The Aviators" to one of his close friends and Chief of Navy's bureau of Aeronautics, William A. Moffett.[179] | [199] | |

| "A Century of Progress" | 1931 | Sousa was requested to compose a march on the hundredth anniversary of Chicago's incorporation as a town in 1933. He composed "A Century of Progress", but passed away few months before the anniversary.[102] | [200] | |

| "The Northern Pines" | 1931 | Inspired by the band at Interlochen, Sousa composed "The Northern Pines" immediately prior to his second visit at the National Music Camp in Interlochen [66] | [201] | |

| "Kansas Wildcats" | 1931 | Sousa was requested to compose a march for Kansas State College. "Kansas Wildcats" was subsequently dedicated to the college.[116] | [202] | |

| "The Circumnavigators Club" | 1931 | "The Circumnavigators Club" was composed and played for the Circumnavigators Club in December 1931. This was Sousa's last composition.[133] | [203] | |

| "Library of Congress" (unfinished) | 1932 | "Library of Congress " was Sousa's last march, which he began composing in 1931. He died leaving the march unfinished. It was later finished by Stephen Bulla.[133] | [12] |

See also

Notes and references

Notes

Sources

- ^ "John Philip Sousa Biography, Marches, & Semper Fidelis". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 37.

- ^ 15 Greatest Marches - John Philip Sousa Songs, Reviews, Credits AllMusic, archived from the original on 11 June 2021, retrieved 11 June 2021

- ^ "John Philip Sousa". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Minnesota March". University of Minnesota Marching Band. University of Minnesota School of Music. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ Frank, Brendan. "The Legacy of Illinois Bands". Illinois Bands. College of Fine and Applied Arts – University of Illinois. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Sousa writes special march for Nebraska". The Daily Nebraskan. Lincoln, Nebraska. 22 February 1928. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "History – Kansas State Bands". Kansas State Bands. Kansas State University Bands. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Student Organizations – Band". Marquette University. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ "Image 10 of Inaugural Ball Program, March 4, 1881". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "John Philip Sousa". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Library of Congress march". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Bierley 1984, p. 80.

- ^ "Review (1876)". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 82.

- ^ Lovrien, David. "Salutation". John Philip Sousa. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Bierley 1984, p. 76.

- ^ Lovrien, David. "The Phoenix March". John Philip Sousa. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Revival (1876)". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bierley 1984, p. 62.

- ^ "The Honored Dead March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, p. 39.

- ^ "Across the Danube (1877)". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 50.

- ^ "Esprit de Corps March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "On the Tramp March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Resumption March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 56.

- ^ "Globe and Eagle March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Our Flirtation March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bierley 1984, p. 79.

- ^ "Recognition March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 59.

- ^ "Guide Right March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 78.

- ^ "President Garfield's Inauguration March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "In Memoriam (President Garfield's Funeral March)". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 81.

- ^ "Right Forward March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Bierley 1984, p. 97.

- ^ "The Wolverine March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, p. 98.

- ^ "Yorktown Centennial March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 47.

- ^ "Congress Hall March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 43.

- ^ "Bonnie Annie Laurie March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 72.

- ^ "Mother Goose March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 77.

- ^ "Pet of the Petticoats March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Right–Left March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 90.

- ^ "Transit of Venus March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bierley 1984, p. 96.

- ^ "The White Plume March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 71.

- ^ "Mikado March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Mother Hubbard March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 84.

- ^ "Sound Off March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Bierley 1984, p. 91.

- ^ "Triumph of Time March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Gladiator March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Rifle Regiment March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 75.

- ^ "The Occidental March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bierley 1984, p. 42.

- ^ "Ben Bolt March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 48.

- ^ "The Crusader March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "National Fencibles March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Semper Fidelis (John Philip Sousa)". LA Phil. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 83.

- ^ "Semper Fidelis March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Picador March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Quilting Party March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, p. 89.

- ^ "The Thunderer March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, p. 95.

- ^ "The Washington Post March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Corcoran Cadets March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 61.

- ^ "The High School Cadets March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 68.

- ^ "The Loyal Legion March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Homeward Bound March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Belle of Chicago March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 70.

- ^ "March of the Royal Trumpets March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, pp. 74–75.

- ^ "On Parade March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Triton March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Beau Ideal March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 67.

- ^ "The Liberty Bell March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 69.

- ^ "Manhattan Beach March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Directorate March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 66.

- ^ "King Cotton March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bierley 1984, p. 44.

- ^ "El Capitan March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "John Philip Sousa A Capitol Fourth PBS". A Capitol Fourth. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Story of 'Stars and Stripes Forever'". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ Van Outryve, Karen. "Appreciating An Old Favorite: Sousa's All-Time Hit." Music Educators Journal 92.3 (2006): 15. Academic Search Complete. Web. April 19, 2012.

- ^ "36 U.S. Code § 304 - National march". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Stars and Stripes Forever March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Bride Elect March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 45.

- ^ "The Charlatan March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, p. 60.

- ^ "Hands Across the Sea March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Man Behind the Gun March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Hail to the Spirit of Liberty March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 64.

- ^ "The Invincible Eagle March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Pride of Pittsburgh March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Imperial Edward March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Jack Tar March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 49.

- ^ "The Diplomat March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bierley 1984, p. 54.

- ^ "The Free Lance March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Powhatan's Daughter March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, p. 51.

- ^ "The Fairest of the Fair March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 57.

- ^ "The Glory of the Yankee Navy March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 52.

- ^ "The Federal March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "From Maine to Oregon March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bierley 1984, p. 46.

- ^ "Columbia's Pride March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Lambs' March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 74.

- ^ "The New York Hippodrome March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Pathfinder of Panama March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 40.

- ^ "March "America First" (1916)". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Boy Scouts of America March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Liberty Loan March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Bierley 1984, p. 73.

- ^ "The Naval Reserve March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, p. 93.

- ^ "US Field Artillery March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The White Rose March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Wisconsin Forward Forever March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "March "Anchor and Star" (1918)". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Bullets and Bayonets March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Chantyman's March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Flags of Freedom March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Sabre and Spurs March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Solid Men to the Front March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, p. 92.

- ^ "USAAC March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 94.

- ^ "The Volunteers March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Wedding March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "John Philip Sousa Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 58.

- ^ "The Golden Star March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Comrades of the Legion March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "On the Campus March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Who's Who in the Navy Blue March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Keeping Step with the Union March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Gallant Seventh March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Dauntless Battalion". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "March of the Mitten Men". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Nobles of the Mystic Shrine". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company (1924)". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "The Black Horse Troop". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Marquette University March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The National Game". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Gridiron Club". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Old Ironsides". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Pride of the Woverines". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Sesquicentennial Exposition March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Bierley 1984, p. 41.

- ^ "The Atlantic City Pageant". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Magna Charta". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Minnesota March". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Riders for the Flag". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Golden Jubilee". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "New Mexico". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Prince Charming". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "University of Nebraska". United States Marine Band. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ schwrtzs (8 January 2018). "John Philip Sousa's "University of Illinois March" December Podcast". Sousa Archives and Center for American Music. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "La Flor de Sevilla (arr Schissel)". Wind Repertory Project. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Daughters of Texas". Wind Repertory Project. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Foshay Tower Washington Memorial March by John Philip Sousa". Wind Band Literature. 7 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Glover, Michael (2007). That Astonishing Infantry': The History of The Royal Welch Fusiliers 1689–2006. Pen and Sword. p. 288. ISBN 978-1473818903. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Lovrien, David. "The Royal Welch Fusiliers". John Philip Sousa. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Bierley 1984, p. 55.

- ^ "George Washington Bicentennial March". Wind Repertory Project. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Lovrien, David. "Harmonica Wizard". John Philip Sousa. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Sousa J. P.: Music for Wind Band, Vol. 15 (Marine Band of the Royal Netherlands Navy, Brion)". www.naxos.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Sousa leads bands of Salvation Army; March Dedicated to Miss Booth Played at Music Festival of Jubilee Congress. City greets delegates, 3,000 March Up Broadway in a Shower of Ticker Tape--Founding Here Recalled. Music Prizes Awarded. Cheered in Broadway Parade. Deegan Welcomes Marchers". The New York Times. 18 May 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Lovrien, David. "The Aviators". John Philip Sousa. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Lovrien, David. "A Century of Progress". John Philip Sousa. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Lovrien, David. "The Northern Pines". John Philip Sousa. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Lovrien, David. "Kansas Wildcats". John Philip Sousa. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Lovrien, David. "The Circumnavigators Club". John Philip Sousa. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

Work cited

Bierley, Paul E (1984). The Works of John Philip Sousa. Columbus, Ohio: Integrity Press. ISBN 9780918048042. LCCN 84080665.