Johnny Appleseed: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Crazytales (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 72.89.167.231 to last version by Khalidkhoso |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses4|the historical figure|the film|Johnny Appleseed (film)}} |

|||

yo dude i had a wicked day on wikipedia and got all this sick info!!! ya!!! hannah montana rocks my freakin' socks!!! g2g eatin rasberry with brown sugar and some big daddy sttrawberrys!!! did you know that my momma mad me those snackies and i have to go number 3 on the toilet!!! bi |

|||

[[Image:JohnnyAppleseedHowe.gif|right|frame|Image from Howe's Historical Collection]] |

|||

hope thats not too much info for you!!! |

|||

GO WIKIPEDIA!!!! |

|||

'''Johnny Appleseed''', born '''John Chapman''' ([[September 26]], [[1774]]–[[March 18]], [[1847]]), was an [[United States|American]] pioneer nurseryman, and [[missionary]] for the [[Swedenborgianism|Church of the New Jerusalem]], founded by [[Emanuel Swedenborg]].<ref name=swedhist>''Swedenborgian history.'' '''Retreived September 9, 2006 from [http://swedenborg.org/jappleseed/history.html http://swedenborg.org/jappleseed/history.html]''' </ref> |

|||

GO NY GIANTS!!! |

|||

He introduced the [[apple]] to large parts of [[Ohio]], [[Indiana]], and [[Illinois]] by planting small nurseries. He became an American [[legend]] while still alive, portrayed in works of [[art]] and [[literature]], largely because of his kind and generous ways, and his leadership in [[Conservation movement|conservation]]. |

|||

==Chapman's family== |

==Chapman's family== |

||

Revision as of 22:37, 5 February 2007

Johnny Appleseed, born John Chapman (September 26, 1774–March 18, 1847), was an American pioneer nurseryman, and missionary for the Church of the New Jerusalem, founded by Emanuel Swedenborg.[1]

He introduced the apple to large parts of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois by planting small nurseries. He became an American legend while still alive, portrayed in works of art and literature, largely because of his kind and generous ways, and his leadership in conservation.

Chapman's family

John Chapman orJo hnny Appleseed was the second child of Nathaniel Chapman and his wife, the former Elizabeth Simonds (m. February 8, 1770) of [ [Leominster, Massachusetts]].[1] Nath niel was a farmer of little means, although tradition holds that h l st two good farms during the American Revolution.[1] His father started John Chapman upon a career as an orchardist by apprenticing him to a Mr. Crawford, who had apple orchards.[2]

A third child, Nathaniel Jr., was born on June 26, 1776, while Nathaniel was an officer leading a company of carpenters attached to General George Washington in New York City. Elizabeth, however, was suffering from tuberculosis, and both mother and child died in July, leaving John and his older sister, also named Elizabeth, to be raised by relatives. After being honorably discharged in 1780, Nathaniel remarried with Lucy Cooley. With ten half-siblings for John and Elizabeth the result. Later around 1803 Elizabeth, John's sister married Nathaniel Rudd.[1]

Heading for the frontier

In 1792, an 18-year-old Chapman went west, taking 11-year-old half-brother Nathaniel, with him. Their destination was the headwaters of the Susquehanna. There are stories of him practicing his nurseryman craft in the Wilkes-Barre area, and of picking seeds from the pomace at Potomac cider mills in the late 1790s.[1]

Land records show that John Chapman was in today's Licking County, Ohio, in 1800. Congress had passed resolutions in 1798 to give land there, ranging from 160 acres to 2240 acres, to Revolutionary War veterans, but it took until 1802 before the soldiers actually received letters of patent to their grants. By the time they arrived, his nurseries, located on the Isaac Stadden farm, had trees big enough to transplant.

Nathaniel Chapman arrived, family in tow, in 1805, although John's sister Elizabeth had married and remained in the east. At that point, the younger Nathaniel Chapman rejoined the elder, and Johnny Appleseed spent the rest of his life alone.

By 1806, when he arrived in Jefferson County, Ohio, canoeing down the Ohio River with a load of seeds, he was known as Johnny Appleseed. He had used a pack horse to bring seeds to Licking Creek in 1800, so it seems likely that the nickname appeared at the same time as his religious conversion. Johnny Appleseed's beliefs made him care deeply about animals.

His concern extended even to insects. Henry Howe, who visited all 88 counties in Ohio in the early 1800s, collected these stories in the 1830s, when Johnny Appleseed was still alive:[3]

One cool autumnal night, while lying by his camp-fire in the woods, he observed that the mosquitoes flew in the blaze and were burnt. Johnny, who wore on his head a tin utensil which answered both as a cap and a mush pot, filled it with water and quenched the fire, and afterwards remarked, “God forbid that I should build a fire for my comfort, that should be the means of destroying any of His creatures.” Another time he made his camp-fire at the end of a hollow log in which he intended to pass the night, but finding it occupied by a bear and cubs, he removed his fire to the other end, and slept on the snow in the open air, rather than disturb the bear.

When Johnny Appleseed was asked why he did not marry, his answer was always that two female spirits would be his wives in the after-life if he stayed single on earth.[4] However, Henry Howe reported that Appleseed had been a frequent visitor to Perrysville, Ohio, where Appleseed is remembered as being a constant snuff customer, with beautiful teeth. He was to propose to Miss Nancy Tannehill there - only to find that he was a day late, and she had accepted a prior proposal:[5]

On one occasion Miss PRICE’s mother asked Johnny if he would not be a happier man, if he were settled in a home of his own, and had a family to love him. He opened his eyes very wide–they were remarkably keen, penetrating grey eyes, almost black–and replied that all women were not what they professed to be; that some of them were deceivers; and a man might not marry the amiable woman that he thought he was getting, after all.

Now we had always heard that Johnny had loved once upon a time, and that his lady love had proven false to him. Then he said one time he saw a poor, friendless little girl, who had no one to care for her, and sent her to school, and meant to bring her up to suit himself, and when she was old enough he intended to marry her. He clothed her and watched over her; but when she was fifteen years old, he called to see her once unexpectedly, and found her sitting beside a young man, with her hand in his, listening to his silly twaddle.

I peeped over at Johnny while he was telling this, and, young as I was, I saw his eyes grow dark as violets, and the pupils enlarge, and his voice rise up in denunciation, while his nostrils dilated and his thin lips worked with emotion. How angry he grew! He thought the girl was basely ungrateful. After that time she was no protegé of his.

Chapman's apples

It is impossible to produce named-variety apples by planting seeds; every tree produces a new variety, often misshapen and sour.[6] To produce apples such as are sold in supermarkets, scions from a named variety must be grafted onto the scrub apple. Chapman did not do that; he considered grafting to be "absolute wickedness".[7] Still, there was not much available in the way of sweets on the frontier, especially during the winter. Whole apples can be stored in a root cellar for months,[8] and snitz (dried apple sections) keep for a year before losing quality.[9]

What's more, apples could be juiced for apple butter or to produce hard cider (which could be further processed to make applejack).[10] Although Cecil Adams's staff claims Chapman drank,[11] Swedenborgian theology required vegetarianism and abstention from alcohol,[12] and it is known that on the night before he died, it was milk he drank with his bread.[13]

On the frontier, water supplies were often of questionable quality, and alcoholic beverages could be the healthful alternative. This was especially true in or near the Black Swamp, where ague and malaria claimed many lives.[14] The Worth farm, where Johnny Appleseed died,[15] and his Milan Township nursery were both in Allen County, Indiana, on the west edge of the Black Swamp. Chapman had introduced "mayweed" (now called dog fennel) into Ohio, giving housewives fresh herbs along with stories for the whole family.[1] He believed dog fennel had antimalarial properties.[16] Farmers called it johnny weed;[17] many states now classify dog fennel as a noxious weed.[18]

Johnny's business plan

The popular image of Johnny Appleseed had him spreading apple seeds randomly, everywhere he went. In fact, he planted nurseries rather than orchards, built fences around them to protect them from livestock, left the nurseries in the care of a neighbor who sold trees on shares, and returned every year or two to tend the nursery.[19]

Appleseed's managers were asked to sell trees on credit, if at all possible, but he would accept corn meal, cash or used clothing in barter. The notes did not specify an exact maturity date - that date might not be convenient - and if it did not get paid on time, or even get paid at all, Johnny Appleseed did not press for payment. Setting down roots in the community - both literally and figuratively - settlers knew that paying their debts was imperative. Appleseed was hardly alone in this pattern of doing business. What was unique was the fact that he remained an itinerant his entire life.[1]

He obtained the apple seed for free; cider mills wanted more apple trees planted, as it would eventually bring them more business. Johnny Appleseed dressed in the worst of the used clothing he received, giving away the better clothing he received in barter. He wore no shoes, even in the snowy winter. There was always someone in need he could help out, for he did not have a house to maintain. When he heard a horse was to be put down, he had to buy the horse, buy a few grassy acres nearby, and turn the horse out to recover. If it did, he would give the horse to someone needy, exacting a promise to treat the horse humanely.[20]

Towards the end of his career, he was present when an itinerant missionary was exhorting to an open-air congregation in Mansfield, Ohio. The sermon was long and quite severe on the topic of extravagance, as the pioneers were now starting to buy such indulgences as calico, and store-bought tea. "Where now is there a man who, like the primitive Christians, is traveling to heaven bare-footed and clad in coarse raiment?" the preacher repeatedly asked, until Johnny Appleseed, his endurance worn out, walked up to the preacher, put his bare foot on the stump which had served as a lectern, and said, "Here's your primitive Christian!" The flummoxed sermonizer dismissed the congregation.[13]

He was generous with the Swedenborgian church as well. He swapped 160 acres of land near Wooster, Ohio in 1821 in exchange for Swedenborgian tracts that he could distribute.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). He would tear a few pages from one of Swedenborg's books and leave them with his hosts.

He made several trips back east, both to visit his sister, and to replenish his supply of Swedenborgian literature. He typically would visit his orchards every year or two, and collect his earnings.

Health

It has been suggested that Johnny may have had Marfan syndrome, a rare genetic disorder.[21] One of the primary characteristics of Marfan Syndrome is extra-long and slim limbs. All sources seem to agree that Johnny Appleseed was slim, but while other accounts suggest that he was tall, Harper's describes him as "small and wiry".

Those who propose the Marfan theory suggest that his compromised health may have made him feel the cold less intensely. His long life, however, suggests he did not have Marfan's, and while Marfan's is closely associated with death from cardiovascular complications, Johnny Appleseed died in his sleep, from winter plague - presumably pneumonia.

Grave site

There is some vagueness concerning the date of his death and his burial. Harper's New Monthly Magazine of November, 1871 (which is taken by many as the primary source of information about John Chapman) says he died in the summer of 1847.[13] The Fort Wayne Sentinel, however, printed his obituary on March 22, 1845, saying that he died on March 18:[22]

On the same day in this neighborhood, at an advanced age, Mr. John Chapman (better known as Johnny Appleseed).

The deceased was well known through this region by his eccentricity, and the strange garb he usually wore. He followed the occupation of a nurseryman, and has been a regular visitor here upwards of 10 years. He was a native of Pennsylvania we understand but his home—if home he had—for some years past was in the neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio, where he has relatives living. He is supposed to have considerable property, yet denied himself almost the common necessities of life—not so much perhaps for avarice as from his peculiar notions on religious subjects. He was a follower of Swedenborg and devoutly believed that the more he endured in this world the less he would have to suffer and the greater would be his happiness hereafter—he submitted to every privation with cheerfulness and content, believing that in so doing he was securing snug quarters hereafter.

In the most inclement weather he might be seen barefooted and almost naked except when he chanced to pick up articles of old clothing. Notwithstanding the privations and exposure he endured he lived to an extreme old age, not less than 80 years at the time of his death — though no person would have judged from his appearance that he was 60. "He always carried with him some work on the doctrines of Swedenborg with which he was perfectly familiar, and would readily converse and argue on his tenets, using much shrewdness and penetration.

His death was quite sudden. He was seen on our streets a day or two previous.”

The actual site of his grave is disputed as well. Developers of Fort Wayne, Indiana's Canterbury Green apartment complex and golf course claim his grave is there, marked by a rock. That is where the Worth cabin in which he died sat.[23]

However, Steven Fortriede, director of the Allen County Public Library (ACPL) and author of the 1978 "Johnny Appleseed", believes another putative gravesite, one designated as a national historic landmark and located in Johnny Appleseed Park in Fort Wayne,[24] is the correct site.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). According to an 1858 interview with Richard Worth Jr., Chapman was buried "respectably" in the Archer cemetery, and Fortriede believes use of the term "respectably" indicates Chapman was buried in the hallowed ground of Archer cemetery instead of near the cabin where he died.[23]

John H. Archer, grandson of David Archer, wrote in a letter[25] dated

The historical account of his death and burial by the Worths and their neighbors, the Pettits, Goinges, Porters, Notestems, Parkers, Beckets, Whitesides, Pechons, Hatfields, Parrants, Ballards, Randsells, and the Archers in David Archer's private burial grounds is substantially correct. The grave, more especially the common head-boards used in those days, have long since decayed and become entirely obliterated, and at this time I do not think that any person could with any degree of certainty come within fifty feet of pointing out the location of his grave. Suffice it to say that he has been gathered in with his neighbors and friends, as I have enumerated, for the majority of them lie in David Archer's graveyard with him

The Johnny Appleseed Commission to the Common Council of the City of Fort Wayne reported, "as a part of the celebration of Indiana's 100th birthday in 1916 an iron fence was placed in the Archer graveyard by the Horticulture Society of Indiana setting off the grave of Johnny Appleseed. At that time, there were men living who had attended the funeral of Johnny Appleseed. Direct and accurate evidence was available then. There was little or no reason for them to make a mistake about the location of this grave. They located the grave in the Archer burying ground."[26]

Legacy

Despite his best efforts to give his wealth to the needy, Johnny Appleseed left an estate of over 1200 acres of valuable nurseries to his sister, worth millions even then, and far more now.[11] He could have left more if he had been diligent in his bookkeeping. He bought the southwest quarter (160 acres) of section 26, Mohican Township, Ashland County, Ohio, but never got around to recording the deed, and lost the property.[16]

The financial panic of 1837 took a toll on his estate.[27] Trees only brought two or three cents each,[27] as opposed to the "fip-penny bit" that he usually got.[28] Some of his land was sold for taxes following his death, and litigation ate much of the rest.[27]

A memorial, in Fort Wayne's Swinney Park, purports to honor him, but not to mark his grave. At the time of his death, he owned four plots in Allen County, Indiana including a nursery in Milan Township, Allen County, Indiana with 15,000 trees.[23]

Since 1975, a Johnny Appleseed Festival has been held in mid-September in Johnny Appleseed Park. Musicians, demonstrators, and vendors dress in early 19th century dress, and offer food and beverages which would have been available then.[29] An outdoor drama is also an annual event in Mansfield, Ohio.[30]

March 11 or September 26 are sometimes celebrated as Johnny Appleseed Day. The September date is Appleseed's ackowledged birthdate, but the March date is sometimes preferred because it is during planting season, even though it is disputed as the day of his death.

Marketing the story

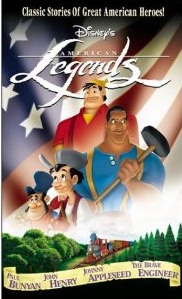

Thousands of books and many films have been based on the life of Johnny Appleseed.[31]

One of the more successful films was Melody Time, the animated 1948 film from Walt Disney Studios featuring Dennis Day. A 19-minute segment tells the story of an apple farmer who sees others going west, wistfully wishing he was not tied down by his orchard, until an angel appears, singing an apple song, setting Johnny on a mission. When he treats a skunk kindly, all animals everywhere thereafter trust him. The cartoon features lively tunes, and a childlike simplicity of message, offering a bright, well-groomed park environment instead of a dark and rugged malarial swamp, friendly, pet-like creatures instead of dangerous animals and a complete lack of hunger, loneliness, disease, and extremes of temperature.[32]

Supposedly, the only surviving tree planted by Johnny Appleseed is on the farm of Richard and Phyllis Algeo of Nova, Ohio[33] Some marketers claim it is a Rambo,[34] although the Rambo was introduced to America in the 1640s by Peter Gunnarsson Rambo,[35] more than a century before John Chapman was the apple of his mother's eye. Some even make the claim that the Rambo was "Johnny Appleseed's favorite variety",[36] ignoring the fact that he had religious objections to grafting, and preferred wild apples to all named varieties. It appears most nurseries are calling the tree the "Johnny Appleseed" variety, rather than a Rambo. Unlike the mid-summer Rambo, the Johnny Appleseed variety ripens in September, and is a baking/applesauce variety similar to an Albemarle Pippen. Nurseries offer the Johnny Appleseed tree as an immature apple tree for planting, with scions from the Algeo stock grafted on them.[37] Orchardists do not appear to be marketing the fruit of this tree.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Swedenborgian history. Retreived September 9, 2006 from http://swedenborg.org/jappleseed/history.html

- ^ "Johnny Appleseed, Orchardist", prepared by the staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen Couth, November, 1952, page 4

- ^ Howe, Henry (1903). Richland County. Howe's Historical Collections of Ohio (485), New York:Dover.

- ^ (1871) Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero, "Harper's New Monthly Magazine", LXIV, 833

- ^ Howe, Henry (1903). Richland County. Howe's Historical Collections of Ohio (260), New York:Dover.

- ^ Apples From Seeds FAQ. Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.pollinator.com/appleseeds_faq.htm

- ^ (1871) Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero, "Harper's New Monthly Magazine", LXIV, 834

- ^ How to store apples for a long long time. Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.backwoodshome.com/articles/fallick41.html

- ^ Packaging and Storing Dried Foods Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.uga.edu/nchfp/how/dry/pack_store.html

- ^ Making applejack. Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.eckraus.com/wine-making-applejack.html

- ^ a b The Straight Dope on Johnny Appleseed. Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.straightdope.com/mailbag/mjappleseed.html

- ^ History of Philadelphia church Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.swedenborg.org/documents/history_of_bible_christian_church.pdf

- ^ a b c (1871) Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero, "Harper's New Monthly Magazine", LXIV, 836

- ^ Black Swamp people Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.nwoet.org/swamp/PDF/black_swamp_people.PDF#search=%22black%20swamp%20ague%22

- ^ PA road marker. Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=489

- ^ a b (1871) Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero, "Harper's New Monthly Magazine", LXIV, 835

- ^ Swedenborgian history Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://swedenborg.org/jappleseed/history.html

- ^ Dog fennel Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=ANCO2

- ^ (1871) Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero, "Harper's New Monthly Magazine", LXIV, 830-831

- ^ "Johnny Appleseed, Orchardist", prepared by the staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen Couth, November, 1952, page 26

- ^ Marfan Syndrome Resource Page Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.dataformato.com/Mag-to-Mar/marfan_syndrome.php

- ^ Obituaries, The Fort Wayne Sentinel, V. 67, No. 81, March 22, 1845

- ^ a b c Researcher finds slice of Johnny Appleseed's life that may prove his burial spot by Kevin Kilbane, The News-Sentinel, September 18, 2003 accessed September 8, 2006 from the Wayback machine http://web.archive.org/web/20050214084049/http://www.fortwayne.com/mld/newssentinel/6803587.htm

- ^ Man and Myth Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.in.gov/ism/Education/Johnny_Appleseed.pdf#search=%22Johnny%20Appleseed%3A%20Man%20and%20Myth%22

- ^ John H. Archer letter, dated October 4, 1900, in Johnny Appleseed collection of Allen County Public Library, Fort Wayne IN

- ^ Report of a Special Committee of the Johnny Appleseed Commission to the Common Council of the City of Fort Wayne, December 27,1934

- ^ a b c "Johnny Appleseed, Orchardist", prepared by the staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen Couth, November, 1952, page 26

- ^ "Johnny Appleseed, Orchardist", prepared by the staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen Couth, November, 1952, page 17

- ^ Johnny Appleseed Festival Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.johnnyappleseedfest.com/

- ^ The Johnny Appleseed Outdoor Drama Retrieved September 5, 2006 from http://www.jahci.org/

- ^ A search on Johnny Appleseed in category books at Amazon.com, September 12, 2006 shows 2301 items.

- ^ Johnny Appleseed (1948) Retrieved September 12, 2006 from http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0040494/

- ^ Virginia Berry Farm Retrieved September 12, 2006 from http://virginiaberryfarm.com/Fruit_berry_plants/fruit_trees.htm

- ^ Koontenai Retrieved September 12, 2006 from http://www.fs.fed.us/r1/kootenai/projects/environmental/nepa/qrtly_files/qrtly699.pdf

- ^ Peter Gunnarsson Rambo Retrieved September 12, 2006 from http://www.colonialswedes.org/forefathers/rambo.html

- ^ Virginia Apples Retrieved September 12, 2006 from http://www.virginiaapples.org/kids/appleseed.html

- ^ The Johnny Appleseed Tree Retrieved September 12, 2006 from http://www.historictrees.org/produ_ht/johnappl.htm

See also

External Links

- "Johnny Appleseed: A Pioneer Hero" from Harper's Magazine November 1871