Charles Frohman: Difference between revisions

image |

|||

| (74 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

'''Charles Frohman''' ([[July 15]] [[1856]] – [[May 7]], [[1915]]) was an [[United States of America|American]] [[theatrical producer]]. |

'''Charles Frohman''' ([[July 15]] [[1856]] – [[May 7]], [[1915]]) was an [[United States of America|American]] [[theatrical producer]]. |

||

One of three [[Frohman brothers]] |

One of the three famous [[Frohman brothers]]. Sons of a German-Jewish cigar-maker and aspiring actor who had immigrated from Darmstadt, in the Rhein-Main region of Germany, the brothers were born in Sandusky, Ohio: Daniel in 1851; Gustave in 1854; and Charles in 1856. The year of Charles' birth date is generally erroneously reported as 1860, and his birthday is shown as [[July 16]] on his tombstone, but the correct date is [[July 15]], 1856 (sources: Certified Birth Certificate, Sandusky, Ohio and the 1860 Federal Census for Sandusky, Ohio, which shows: "Charley," age 4). |

||

He was the greatest theatrical manager and producer of his era, and his “Frohmannational Theatricalities” ran from coast to coast and continent to continent. The theater’s dominant figure for more than a quarter of a century, Frohman was short and rotund, and he literally waddled when he walked. Lloyd Morris in ''Curtain Time'' described him as “Squat, bald, sallow-faced, his large, melting eyes alone redeemed him from ugliness.” He was called many names – not all of them complimentary – including the “Beaming Buddha,” "the Little Napoleon of the Theater," and head of the "Holy Frohman Empire." His friends called him simply "C.F." |

|||

Whereas the theater of the melodramatic era had been a loosely-knit community of independent theaters, with actors and actresses basically managing themselves, the new era of big business demanded that performers procure the services of a personal manager and either sign contracts with an all-controlling theater syndicate, or be left out in the cold with no where to work. By the 1880s the Frohman Brothers had become the leading theatrical managers and producers in New York City. |

|||

American drama was at its lowest point when the Frohmans came along but, by importing the best foreign playwrights and developing the star system, they took a fairly informal and scattered profession and turned it into a highly profitable enterprise. Although they were criticized for doing little to encourage native playwrights, they gave the theater an entirely new direction, as well as an aura of dignity and respectability. Charles Frohman's plays were based on romance, sentiment, and light comedy. He abhorred death scenes and eschewed indecency. And, he created the “Star” system which revolutionized the theater and is still with us today. |

|||

==Life and career== |

==Life and career== |

||

In 1864, Frohman's family moved to New York City, where Frohman eventually worked for a [[newspaper]]. In New York, Frohman developed a love of the theatre that led to him becoming a booking agent and then working his way up to producer and theatre owner/operator. |

In 1864, Frohman's family moved to New York City, where Frohman eventually worked for a [[newspaper]]. In New York, Frohman developed a love of the theatre that led to him becoming a booking agent and then working his way up to producer and theatre owner/operator. |

||

When Charles became an independent manager in 1883, he launched – as his first production – [[David Belasco]]’s ''The Strangers of Paris'' at the New York Theatre. He lost money on the deal; but that wasn’t important. Charles Frohman, at 23 years of age, had produced his first play, and nothing could have made him happier. |

|||

Frohman's first success as a producer was with [[Bronson Howard]]'s ''[[Shenandoah]]'' (1889). Frohman founded the Empire Theatre Stock Company to acquire the Empire Theatre in 1892, and the following year produced his first [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] play [[Clyde Fitch|Clyde Fitch's]] ''[[Masked Ball]]''. This play marked the first time that [[actress]] [[Maude Adams]] played opposite [[John Drew, Jr.|John Drew]], which led to many future successes. Soon he acquired five other New York City theaters. |

|||

Two more shows failed, and then he produced ''Caprice'' with [[Henry Miller]]. For Miller’s leading lady, Frohman chose the young [[Minnie Maddern]]. ''Caprice'' was a hit, and it made her a star. He put five plays on [[Broadway]] in 1886, and two in 1887, including ''She'', a romantic adventure story adapted by [[William Gillette]] from [[Rider Haggard]]’s novel of the same name, which opened to great acclaim at Niblo’s Garden in New York on November 29. |

|||

Frohman was known for his ability to develop talent. His stars included [[John Drew]], [[Ethel Barrymore]], [[E. H. Sothern]], [[Julia Marlowe]], [[Maude Adams]], and [[Henry Miller]]. In 1896, Frohman, [[Al Hayman]], [[Abe Erlanger]], [[Marcus Klaw|Mark Klaw]], [[Samuel F. Nixon]], and [[Fred Zimmerman]] formed the [[Theatrical Syndicate]]. Their organization established systemized booking networks throughout the United States and created a monopoly that controlled every aspect of contracts and bookings until the late 1910s when the [[Shubert brothers]] broke their stranglehold on the industry. |

|||

But, up to this time, Frohman had not scored the smashing success he needed to make his name and fortune. Then, in early 1889 he found his audience with [[Bronson Howard]]'s ''Shenandoah''. After ''Shenandoah'' put him on top, Frohman opened his opulent office at 1127 Broadway; there he began hatching his legendary successes. In 1890 he leased Proctor’s Twenty-third Street Theatre and established the Charles Frohman Stock Company. After mounting Gillette’s ''The Private Secretary'' at the Grand Opera House on August 26, he launched Gillette’s ''All the Comforts of Home'' at Proctor's on September 8, starring [[Henry Miller]] and introducing to new acclaim a delicate and elfin young actress named [[Maude Adams]]. |

|||

In 1893 he produced his first [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] play [[Clyde Fitch|Clyde Fitch's]] ''[[Masked Ball]]''. This play marked the first time that [[actress]] [[Maude Adams]] played opposite [[John Drew, Jr.|John Drew]], which led to many future successes. Soon he acquired five other New York City theaters. |

|||

On January 25, 1893, he opened his fabulous Empire Theatre on the corner of Broadway and 40th Street, near the [[Metropolitan Opera House]], then only ten years old. It was not an auspicious location, sitting as it did so far from the center of the Union Square Theatre District and bordering on the city’s notorious red light district, called the [[Tenderloin]]. It also sat a mere two blocks from [[Longacre Square]], an unlit intersection in midtown Manhattan at 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue popularly called the Thieves’ Lair because of its rollicking forms of low entertainment and its correspondingly high level of crime. The Broadway Theater was the only other uptown theater at the time. |

|||

All of this, of course, was no cause for concern for the man who never worried to begin with; he would simply make his productions so irresistible that people would cross mighty oceans and burning deserts to see them, not to mention of few extra blocks in [[Manhattan]]. In fact, along with playgoers, other producers would build their theaters to the vicinity of the Empire, thus establishing a new theatrical district in New York. This became the heart of the Broadway theater district and pushed the northern edge of the Rialto to the southern border of the Thieves’ Lair, which later obtained half the world’s share of electric lighting and, in 1904 by proclamation of Mayor [[George B. McClellan, Jr.]] (the general’s son), was renamed [[Times Square]]. |

|||

Frohman had always been one to see value in big names. In his era, the star carried the play, rather than the reverse. The problem under the old system was that performers became "stars" only after having paid their dues and climbing through the ranks. It was a long and tedious process for which Frohman had neither time nor patience. He needed stars to put his plays across and, if he intended to make rather than acquire them, then he had to work quickly and focus his attention on the actors in his charge. Comparing a play to a dinner, he said, "To be a success, no matter how splendidly served, the menu should always have one unique and striking dish that, despite its elaborate gastronomic surroundings, must long be remembered." |

|||

Thus, he became known for his ability to develop talent. Rather than take on established stars, he took unknowns and made them into stars. The only established stars he signed up -- by way of launching his empire -- were [[John Drew]] and [[William Gillette]], but those he made into stars included [[Billie Burke]]. [[Nat Goodwin]], [[Elsie De Wolfe]], [[Arthur Bryon]], [[Edna May]], [[Annie Russell]], [[Margaret Anglin]], [[Marie Tempest]], [[E. H. Sothern]], [[Otis Skinner]], [[Julia Marlowe]], [[Seymour Hicks]], [[Marie Doro]], [[Henry Miller]], [[Arnold Daly]], and the entire Barrymore family – [[Maurice Barrymore]] and his three offspring [[John Barrymore]], [[Ethel Barrymore]], and [[Lionel Barrymore]]. As a producer, he produced the works of [[George Bernard Shaw]], [[Oscar Wilde]], [[James M. Barrie]], [[Haddon Chambers]], [[Henry de Mille]], [[John Galsworthy]], [[Alfred Sutro]], and [[Harly Granville-Barker]]. He also produced all of [[Somerset Maugham]]'s plays in the United States, most of them successfully, and was responsible for Maugham’s great popularity in America. |

|||

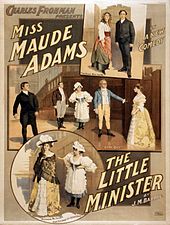

[[Image:Maude Adams in The Little Minister.jpg|thumb||left|upright|Charles Frohman presents Miss Maude Adams in ''The Little Minister'', by J. M. Barrie]] |

[[Image:Maude Adams in The Little Minister.jpg|thumb||left|upright|Charles Frohman presents Miss Maude Adams in ''The Little Minister'', by J. M. Barrie]] |

||

In 1897, Frohman leased the [[Duke of York's Theatre]] in London, introducing plays there as well as in the United States. [[Clyde Fitch]], [[James M. Barrie|J. M. Barrie]], and [[Edmond Rostand]] were among the playwrights he promoted. As a producer, among Frohman's most famous successes |

In 1897, Frohman leased the [[Duke of York's Theatre]] in London, introducing plays there as well as in the United States. [[Clyde Fitch]], [[James M. Barrie|J. M. Barrie]], and [[Edmond Rostand]] were among the playwrights he promoted. As a producer, among Frohman's most famous successes were Barrie's ''[[Peter Pan]]'' with [[Maude Adams]] and [[William Gillette]]'s ''[[Sherlock Holmes]]'' starring Gillette himself in his most celebrated role. In the early years of the [[20th century]], Frohman also established a successful partnership with [[Seymour Hicks]] to produce musicals and other comedies in London, including ''[[Quality Street (play)|Quality Street]]'' in 1902, ''[[The Admirable Crichton]]'' in 1903, ''[[The Catch of the Season]]'' in 1904, ''[[The Beauty of Bath]]'' in 1906, ''The Gay Gordons'' in 1907, and ''[[A Waltz Dream]]'' in 1908, among others. He also partnered with other London theatre managers. The system of exchange of successful plays between London and New York was largely a result of his efforts. In 1910, Frohman attempted a repertory scheme of producing plays at the Duke of York's. He advertised a bill of plays by [[J. M. Barrie]], [[John Galsworthy]], [[Harley Granville Barker]], and others. The venture began tentatively, and while it may have proved successful, Frohman canceled the scheme when London theatres closed at the death of [[King Edward VII]] in February 1910. |

||

Frohman was the first manager to distribute what would later be called "press releases," sending to the newspapers stylographic press sheets containing news of his many attractions. And he employed delicate touches to celebrate his successes. On the night of the 300th performance of Barrie’s ''The Little Minister'', which starred [[Maude Adams]], Frohman gave an American Beauty rose, complete with the necessary pin, to every woman in the audience. Another of his theatrical “firsts” was to order a private railroad car in 1890 for the entire touring company of Men and Women. Many considered it extravagant, but Frohman wanted his people to be comfortable. |

|||

Frohman controlled five theaters in London, six in New York City, and over two hundred more throughout the rest of the United States. By 1915, he had produced more than 700 shows, managed 28 bonafide stars at one time, employed about 10,000 people on his payroll – 700 of them actors – and paid salaries totaling $35 million a year. He controlled six theaters in New York, more than 200 throughout the country, and six more in London. In 1904 alone he had ten plays running in London at the same time. Actors on both sides of the Atlantic vied for his managerial genius, and many appeared on stages in both England and the United States. As the saying went, "Frohman takes America to England and brings England back to America." |

|||

==The Theatrical Syndicate== |

|||

In 1896, Frohman, [[Al Hayman]], [[Abe Erlanger]], [[Marcus Klaw|Mark Klaw]], [[Samuel F. Nixon]], and [[Fred Zimmerman]] formed the [[Theatrical Syndicate]], which owned or controlled many theaters throughout the United States. It had been formed in secret, in the Holland House, by Frohman, Marc Klaw, Al Hayman, Abraham Lincoln Erlinger, Samuel F. Nirdlinger, and J. Frederick Zimmerman. The six conspirators signed on August 31 the Syndicate Agreement which cited the problems with the current booking system and proposed the formation of this syndicate as the remedy for those problems. They felt that the only solution to the chaos of the theatrical world was centralized booking. Through the auspices of the Syndicate, cross-country bookings became standardized. Without any great expense, a troupe manager could book an entire tour. Conflicting engagements were eliminated, as well as the booking of two major productions in the same town at the same time. The new Syndicate established systemized booking networks throughout the United States and created a monopoly that controlled every aspect of contracts and bookings. |

|||

What precisely Frohman's role was in the Theatrical Syndicate remains a matter of dispute. For one thing, he already had a kingdom of his own and didn't need them as much as they needed him. "His supporters," Gerald Bordman explained, "have claimed that he was the idealist in the group, looking the other way at its shady practices because he felt more benefits than harm came from its methods. Others have seen him as playing Spenlow to Erlanger's Jorkins. Most likely the truth lies somewhere in between. But the certainty of comfortable bookings allowed him to work with ease, develop a roster of great stars, and present a steady stream of popular plays." |

|||

Within weeks, all the theaters under the Syndicate’s control were organized into one nationwide chain, with the Syndicate serving as a clearing house through which all business was transacted. As Ward Morehouse described it in ''Matinee Tomorrow'', “The Syndicate gained control of the great majority of the playhouses of America, its operations extending from New York to New Orleans, from New Orleans to California. The road theaters were put into one great national chain. Numerous cities became so tightly controlled that nonsyndicate attractions could not enter... Managements unwilling to accept the terms of the Syndicate – and tough terms they generally were – had the alternative of booking in independent houses, and these were generally nonexistent." |

|||

It was intended to greatly simplify things, and it might have if its business had been conducted honorably; but it wasn’t. Rivals were hard-pressed to resist this monopoly; those who did were bribed or browbeaten into joining. Nevertheless, Frohman added his pristine reputation and his illustrious chain of theaters to the combine and retained a one-sixth interest in it for the sixteen years it dominated the American stage. |

|||

“Here was the crux of the matter,” John Anderson wrote in The American Theatre. “The theatre, as a local institution, became not a theatre so much as an investment in real estate which had to yield its utmost in revenue. The way was open for one of those peaceful but eventful revolutions which the world passes through without ever realizing what is happening. The men who had no interest, either as landlords or artists, quietly but firmly seized control of the theatre. The booking agency became the absolute dictator of amusement in virtually every town in the United States. When the local managers became mere branch executives for a central booking office in New York the Syndicate was supreme. By the most approved methods of Big Business, in an age of industrial feudalism (not to say piracy) the theatre calmly, and for the most selfish reasons, surrendered and obligingly choked itself to death.” |

|||

Beguiled by Frohman’s charming manner, well-deserved reputation for integrity, and genuine love for the theater, most theater-owners, managers and performers acquiesced, realizing that it was to their benefit. |

|||

With all of the Syndicate’s promise, however, problems almost immediately arose. Tribune Critic William Winter called it “The Incubus,” “an appropriate title,” Craig Timberlake concluded, “since most of the actor-managers and independent producers were sound asleep when visited by this nightmarish apparition. At first, theater managers had no complaint against the Trust. The reorganization of the theater eliminated wasteful competition, unsnarled the tangle of bookings and brought a new order and discipline to their business. Initial criticism of the Syndicate emanated from the actor-managers who refused to accept the dictation of Klaw and Erlinger.” |

|||

Several prominent stars resisted, the most vocal and volatile being Maurice Barrymore, scion of the Barrymore clan, who never missed an opportunity to utter scathing soliloquies against the Syndicate from any stage or sidewalk. Richard Mansfield became a leading spokesman for the cause, but the most notable resisters were Minnie Maddern Fiske and her husband, Harrison Grey Fiske, publisher of the Dramatic Mirror, a theatrical journal which maintained a neutral stance on the controversy. Others who resisted included Joseph Jefferson, Nat Goodwin, Sarah Bernhardt, and Francis Wilson, as well as producers David Belasco and Henry W. Savage. |

|||

In spite of the problems it caused, [[Maude Adams]] always stuck up for the syndicate: “It never seemed to me they judged the advantages of the Syndicate squarely with the disadvantages. The advantages were a well-planned, carefully maintained field of operation – the theatres in excellent condition with well-trained constantly employed stagehands; the front of the house well kept; the box office well guarded; the advertisements, the newspapers all attended to; the confusion of independence bookings corrected.” |

|||

Yet, those who defended it never took into account the ruthlessness of Frohman’s partners. John Perry pointed out, “The syndicate made big promises, which the American theatre bought because of its chaotic conditions... The syndicate offered a package deal that guaranteed actors a full season on the road with advance promotion, managers a full season showcase, and producers lots of revenue. The catch was that everyone lost their independence and the syndicate enforced grudges, punishing dissenters ruthlessly.” |

|||

Actors who refused to join the Syndicate were barred from its theaters and had to make do as best they could. When the Syndicate refused to allow Sarah Bernhardt the use of their stages, she – with peg-leg to walk on and coffin to sleep in – declared she would appear in any auditorium, school, or skating rink where she could perform, and was thus banished to skating rinks in Atlanta, Savannah, Augusta, Jacksonville and Tampa. In Texas, however, even the skating rinks were closed, so Bernhardt performed throughout Texas beneath large tents, although on the West Coast she was able to perform in theaters after the Syndicate relaxed its stranglehold. |

|||

It was a dictatorial monopoly, pure and simple, a fact that had not been of much concern in 1896, when Trusts were formed everywhere, but which created a major public relations problem after the turn of the century when President Theodore Roosevelt was enforcing the Sherman Anti-Trust Laws. The mood of the public had turned against monopolies, and newspapers, particularly the New York World, attacked this one. But none of them had any idea that the cavalry would soon come to their rescue. At the turn of the century, just when the Syndicate loomed over the theater like an all-powerful Colossas of Rhodes, it was suddenly challenged by the arrival of the Shubert Brothers from Syracuse. |

|||

With financial backing from a Syracuse haberdasher, the Syracuse troika came to the big city deliberately to take on the Trust. Thus began a bitter war that would consume both sides – and the theater with it – for the next fifteen years, and the cost was high. Actors and managers were caught in the cross-fire, and in taking down the Trust, the Shuberts brought down the Theatre with it. The Shuberts themselves soon behaved no better than their rivals. As their empire grew, the Shuberts built theaters all across the country, and the country was soon glutted with theaters. Newspapers began referring to the “two syndicates” and bestowed the same printed abuse on the Shuberts as they had on the original Trust. Archie Binns, Minnie Maddern Fiske’s biographer, noted, “The original avowed aim of the Syndicate had been to end the duplication of booking agencies – and the final result was a ruinous duplication of theatres. Out of disorder it brought anarchy.” |

|||

The Shubert Brothers empire far outlasted the Syndicate and maintained control of the American theater for many years to come. At the time of the Great Depression, Shubert productions were appearing in more than a thousand theaters from coast to coast. By the end of the twentieth century, the Shubert Organization owned 16 theaters on Broadway as well as the National Theater in Washington, D.C., and two out of every three theater tickets sold were for Shubert productions. |

|||

==Frohman’s Greatest Gift== |

|||

Odd though he was, Frohman made friends easily; and one of his most endearing friendships was with [[James M. Barrie]]. Convinced by Frohman, against his will, to become a playwright, Barrie dramatized ''The Little Minister'' in 1897. It ran for six months in New York, toured the country, and turned [[Maude Adams]] into a bonafide star. This paved the way in 1901 for ''Quality Street'', Barrie’s greatest success, much of which he owed to Frohman. Starring Adams, it established Barrie among the foremost playwrights of his era. Barrie found another devoted admirer in [[William Gillette]]. In 1903 ''The Admirable Crichton'' gave the world one of Gillette’s finest performances. ''Dear Brutus'' in 1918 would be another major milestone with Gillette again leading an all-star cast with his dream daughter played by 18-year-old [[Helen Hayes]]. |

|||

But the greatest gift Barrie and Frohman would give to the world was a whimsical little play of childhood imagination and nonsense. It was based on Barrie's novel, the first line of which reads, "All children, except one, grow up." |

|||

"I have written a play for children,” Barrie wrote to Maude Adams on April 18, 1904, “which I don’t suppose would be much use in America. She is rather a dear of a girl with ever so many children long before her hair is up and the boy is Peter Pan in a new world. I should like you to be the boy and the girl and most of the children and the pirate captain." |

|||

The play was written for Adams, and the feminine lead was modeled after her soft, elfin personality. Barrie went to Frohman with the play but was ill at ease. When Frohman asked him why, Barrie said, "You know I have an agreement to deliver you the manuscript of a play?" |

|||

Frohman said, "Yes." |

|||

"Well," Barrie continued, "I have it, all right, but I am sure it will not be a commercial success. But it is a dream-child of mine, and I am so anxious to see it on the stage that I have written another play which I will be glad to give you and which will compensate you for any loss on the one I am so eager to see produced." |

|||

"Don’t bother about that," was Frohman’s typical reply. "I will produce both plays." |

|||

"Frohman's faith in Barrie was marvelous," Daniel later commented. "It was often said in jest in London that if Barrie had asked Frohman to produce a dramatization of the Telephone Directory he would smile and say with enthusiasm: 'Fine! Who shall we have in the cast?'" |

|||

Barrie’s "substitute play" was ''Alice-Sit-by-the-Fire'', starring [[Ethel Barrymore]], which opened on Christmas Day 1905 and ran for a year. Although a hit at the time, it is hardly remembered today, while Barrie’s dream child, for which he had such scant hopes, was ''[[Peter Pan]]'', still in regular production more than a century after its debut. |

|||

==Frohman Speak== |

|||

Part of Frohman’s charm was his conversational style which was, to say the least, unique. "His ideas were so great that their very presence seemed to overwhelm his utterance," [[Otis Skinner]] explained. "The mental pictures he saw, he lacked power to describe. At rehearsal he would run into a verbal hiatus now and then – but always by gesture or an expression of his face managed to make his meaning known. He seemed to have a timidity in the presence of language. But if his tongue faltered his eyes conveyed his message. They were eloquent eyes. He would begin– 'Er–a–Otis–you know–a–you know–er–' |

|||

“‘Yes, Charlie,’ I would reply, 'I know. I've got it.' It was a kind of telepathy. One caught his meaning before he spoke.” |

|||

As [[Billie Burke]] put it, “He had almost no system of communication. He spoke in unpunctuated telegrams. Actually, he made his wishes known as much with tight little jabs of his forefinger and his eyes as he did with words, and yet [[Somerset Maugham]], Sir [[Arthur Wing Pinero]] and Sir [[James M. Barrie]] adored him and wrote their best plays for him. It was years before I understood why.” |

|||

[[Montrose Moses]] explained, in part, the “why” when he commented on “the persuasive personality of Charles Frohman, who seems to have had a charm, an irresistibility about him, which none could withstand. The whole record of the Little Napoleon of the Theatre consists in loyalties to and from his actors and dramatists. They loved him; he watched after their interests, and nothing was too great a task for him, when he wanted to bring some one to success. He interpreted the theatre in his own way; and this interpretation became at once the standard and the limitation of all American theatrical managers of the time. For Frohman was a leader, against whom it was difficult to compete.” |

|||

Here is how Frohman explained to a dejected [[William Faversham]] a new part he was to play: “New play–see? ... Fine part.–First act–you know–romantic–light through the window ... nice deep tones of your voice, you see? ... Then, audience say 'Ah!'–then the girl–see?–In the room ... you ... one of those big scenes–then, all subdued–light–coming through window–see?–And then–curtain–audience say great!' ... Now, second act ... all that tremolo business–you know?–Then you get down to work ... a tremendous scene ... let your voice go ... Great climax ... (Oh, a great play this–a great part!) ... Now, last act–simple–nice–lovable–refined ... sad tones in your voice–and, well, you know–and then you make a big hit... Well, now we will rehearse this in about a week – and you will be tickled to death. ... This is a great play–fine part. ... Now, you see Humphreys – he will arrange everything." |

|||

And Faversham left, feeling exultant about his "fine part" in a "great play." |

|||

==Weaknesses== |

|||

The theater was Frohman’s entire life. Completely devoted to it, he never married. Unlike his lecherous friend Belasco, possessor of a true casting cough and large pornography collection, and in spite of rumors that he and Maude Adams were married and that Helen Hayes was their love child, C.F. was not a sexual predator. His own couch was used for himself to sit on, cross-legged, while listening to scripts being read or watching scenes being enacted, or for lounging in times of either moodiness or intense pain from his rheumatism. All of his actresses regarded him with genuine affection and devotion for as long as they lived, which was hardly the case with Belasco. There was never any personal scandal attached to his name, and a visitor to his country place near White Plains, New York, came away declaring that “the real Charles Frohman had three dissipations – he smokes all day, he reads plays all night, and –” |

|||

There he paused. “What is it?” he was asked, to which he replied, “He plays croquet.” |

|||

He went immaculately dressed at all times, yet seemed disdainful of clothes, and he dined well. [[Billie Burke]] remembered, "So far as I was ever able to learn, he never read a book unless he thought they might become plays. Once a reporter asked him what his favorite book was. Frohman replied: 'Roland Strong's The Best Restaurants of Paris.'" |

|||

Frohman was particularly drawn to sweets. [[Lionel Barrymore]] recalled a meeting at Armenonville in the Bois, "where C.F. would go to fill himself with pastries, watermelons, oranges, ices, pies, cakes – mounds and pounds of anything sweet." They always knew how to get what they wanted from him, Barrymore said. All they had to do was take him out and load him down with sweets. Burke recalled, “In New York he and Fitch used to eat pastries in one another’s apartments, being ashamed to consume as many as they wanted in public. In the Bois, C.F. would often pile one delicacy on top of another – watermelon, ice cream, strawberries, muskmelon and cantaloupe, for instance.” |

|||

And [[Otis Skinner]] added, “His weakness for rich foods undoubtedly contributed to a digestive disarrangement that became an all too constant companion, and because he never took physical exercise, presently wrought havoc with his system... |

|||

“He had his weaknesses – amiable ones; the wonder is that they were so few. He was singularly clean; as Augustus Thomas said of him in a masterly funeral oration, to be with him was to come into the presence of decency. He was vain of the eminence he had gained, and loved all references to his power. He always wished to see Charles spelled in full, and was inclined to be peevish over letters addressed to Chas. Frohman. He liked to think of himself as the creator of his theatrical stars – the Pygmalion of many Galateas... And I learned, too, that any assistance in direction from his stars annoyed him somewhat. He wanted to be sole authority in production. He hated to acknowledge himself in the wrong. Once we had a little a little argument about a piece of business in A Celebrated Case. I yielded, though unconvinced. At the next day's rehearsal he said, 'You were right about that scene.' Then seeing my look of satisfaction he added, 'Now don't rub it in.'" |

|||

In a business demanding inflated egos, he was a humble and shy man. Daniel noted, "Charles cared absolutely nothing for honors. He was content to hide behind the mask of his activities. He would never even appear before an audience. Almost unwillingly he was the recipient of the greatest compliment ever paid an American theatrical man in England (election to membership of the British Garrick Club)." |

|||

Barrie wrote, “I have never known any one more modest and no one quite so shy. Many actors have played for him for years and never spoken to him, have perhaps seen him dart up a side street because they were approaching. They may not have known that it was sheer shyness, but it was. I have seen him ordered out of his own theater by subordinates who did not know him, and he went cheerfully away. 'Good men, these; they know their business,' was all his comment. Afterward he was shy of going back lest they should apologize." |

|||

Frohman had a temper and took overmuch pride in his professional eminence. In addition, Skinner’s example notwithstanding, he seldom tolerated anyone questioning his judgment. Once, during a rehearsal, he made a suggestion to [[Mrs. Patrick Campbell]] about a scene she was playing. She reminded him that she was the artist. Turning and walking away, Frohman promised to keep her secret. She never worked for him again. |

|||

==Heroic Death== |

|||

In the autumn of every year, Charles Frohman made his annual trip to Europe to oversee what he called his London and Paris "playmarkets." Equally beguiling were his visits with James Barrie, with whom he always dined at the Savoy on the night of his arrival to England. Frohman had actually planned on sailing toward the end of May, but Barrie was anxious that he arrive as soon as possible to help salvage ''Rosy Rapture'', a play Barrie had staged at the Duke of York’s Theatre but which was failing. Barrie begged, and Frohman complied. He booked passage for the first of May, but he was now a man caught in the winds of change and turmoil. The Great War was on and German [[U-boats]] prowled the seas, sinking anything they thought might be carrying troops, arms and munitions, which was just about every major ship afloat. Crossing the Atlantic was now a very perilous undertaking. |

|||

"[[Al Hayman]], who owned the Empire Theatre and ran the business affairs of the Frohman offices, and I, had tried to dissuade him," [[John Drew]] recalled. "He laughed at us for our fear for him." |

|||

A letter from Frohman to Drew lightheartedly said, "I hope to get away on May first and back shortly after you reach here. I am searching for something for you." |

|||

Drew dashed off a telegram which read, "If you get yourself blown up by a submarine I'll never forgive you." That telegram haunted Drew for the rest of his life. The ship Frohman sailed on was the Cunard Line's R.M.S. ''[[Lusitania]]''. |

|||

Knowing that C.F. was sailing in spite of everybody's concerns, Ethel Barrymore – then playing in Boston – went to see him. |

|||

"What are you doing here, Ethel?" he asked. |

|||

"I thought I would come down to say good-by," she said. |

|||

"They don't want me to go on this boat," he continued. "I had a funny message from von Papen and Captain Boy-Ed, telling me not to go on the Lusitania." |

|||

Ethel was also anxious about it. "Why go then?" she asked. |

|||

"Nonsense, of course I'll go." Then he leaned over and kissed Ethel on the cheek, something he had never done before. All the way back to Boston, Ethel worried about him, but she still felt that nothing could ever happen to Charles Frohman. Before going on stage in the Boston production of The Shadow, Ethel received a telegram from Frohman: “Nice talk, Ethel. Good-by. C.F.” |

|||

However, kissing Ethel on the cheek was not the only unusual thing Frohman did, and it gives rise to the thought that he may have had a premonition of his fate. He acted strangely for days before sailing. “For one thing,” his brother Daniel noted, “he dictated his whole program for the next season before he started. It was something that he had never done before.” Frohman had done this as a precautionary measure, since he was certainly aware of the danger. |

|||

Ann Murdock had sent him a basket shaped like a large steamer, to which he replied in a note later delivered to her by the ship’s pilot: “The little ship you sent is more wonderful than the big one that takes me away from you.” |

|||

Another telegraph concluded, “GOD BLESS YOU DEAR FRIEND.” |

|||

On February 18, 1915, the German Admiralstab had declared that all waters around the British Isles, not including the waters north of Scotland, to be a "War Zone." This meant that ships "would be destroyed even if it is not possible to avoid thereby the dangers which threaten the crews and passengers." Neutral shipping was also in danger, the notice added, "owing to the British misuse of neutral flags." U-boats began sinking ships without warning, leaving passengers and crews to fend for themselves. Yet, in complete disregard of the German warning, the ''[[Lusitania]]'' departed from Pier 54 just after 12:00 noon. |

|||

Ironically, both [[William Gillette]] and songwriter [[Jerome Kern]] were meant to accompany him on the voyage, but Gillette had contractual commitments in Philadelphia and Kern overslept after being kept up late playing requests at a party. |

|||

While he never rested, Frohman needed rest at this time because he was not at all well, suffering from chronic articular rheumatism that left him with severe pain in every joint. He was, for all intents and purposes, immobile, and for a while was bedridden as well, and spent most of the voyage in his cabin. He was feeling better, however, on the morning of May 7 – a bright, clear, sunny day – and entertained guests in his suite. He later sat at his table and regaled friends with anecdotes from his years in the theater. He had just eaten lunch in the early afternoon, and was talking with George Vernon, actress actress [[Rita Jolivet]]’s brother-in-law, and Captain Alick Scott, an English officer who had just joined them, when at 2:10 in the afternoon, about 12 miles off the Old Head of Kinsale, near Queensland, and with the coast of Ireland in sight, the German [[U-boat|submarine]] ''U-20'' or [[Unterseeboot 20]] commanded by Kapitänleutnant [[Walther Schwieger]] launched a G-6-type torpedo which struck on the starboard side, by the No. 1 or No. 2 funnel, toward the bridge. The entire ship rocked but, within a minute, there was a second blast, caused by either ignited coal dust or exploding steam lines. As passengers began to panic, Frohman stood on the promenade deck, chatting with friends and smoking a cigar – the most unperturbed passenger on the ship. He calmly remarked, "This is going to be a close call." He reluctantly allowed Captain Scott to fasten a life-jacket on him, advising the Englishman, "Now, Captain, you must get yourself a life-jacket." He then gave his life-jacket to a woman. "If you must die," Captain Scott told him, "it is only for once." Frohman responded to these words with a whimsical smile. He continued to puff confidently on his cigar. Then he leaned on the rail, gazed out at the sea, and said, almost in a whisper, "I didn't think they would do it." |

|||

The ''[[Lusitania]]'' was soon listing heavily to starboard and sinking toward the bow. In less than 20 minutes she would be gone. Frohman – with a permanently disabled leg and walking with a cane – could hardly have jumped from the deck into a lifeboat, so he was trapped; but he was either unconcerned anyway or else serene in the face of the inevitable. With only minutes in which to save themselves, he and millionaire [[Alfred Vanderbilt]] – arguably the two most gallant men on the ship – were discovered in the nursery, tying life-jackets to "Moses baskets" containing infants who had been asleep in the nursery after lunch. Vanderbilt had given his own life-jacket to one woman, had helped many women and children into lifeboats, and was last seen calmly looking about the deck for others to assist. |

|||

Frohman then went out on the starboard side of the deck. Waves were rushing toward him, wreckage and debris were everywhere, and the sea was climbing. At the final moment, [[Rita Jolivet]], Captain Scott and George Vernon stood at Frohman’s side. To Jolivet he casually said, "You had better hold on the rail and save your strength." Jolivet was terrified of drowning, and carried a pearl-handled pistol with which to end it quickly if she found herself hopelessly submerged; but, in the ship’s dying moments, when she could have legitimately claimed a seat in a lifeboat, she refused to leave Frohman’s side. |

|||

And then Frohman said the words for which he will always be remembered. Paraphrasing his greatest hit, ''[[Peter Pan]]'', he said, "Why fear death? It is the most beautiful adventure of life.” |

|||

On a common impulse, they all moved closer together and joined hands. A serene smile on his face, he was in the middle, once more, of quoting his line from ''[[Peter Pan]]'' – "Why fear death?..." – when "a mighty green cliff of water" swept them off the deck. |

|||

Frohman was only a month and a half short of his 58th birthday. Of the 1,198 people who perished in the tragedy, he was among the 128 Americans lost. |

|||

Jolivet, alone of Frohman’s group, survived. Her account provided the intimate details of his final minutes. Frohman, however, apparently perished, not by drowning, but by a heavy object falling on him. His body was later washed ashore below the Old Head of Kinsale and discovered among the 147 bodies awaiting identification in an improvised morgue in Queenstown. It alone, of all the others, was not disfigured. Wilbur Forrest of the New York ''Tribune'' found the body and later wrote, "There on the floor of the improvised morgue containing bodies of indiscriminate warfare’s innocent victims, most of them with all the agonizing emotions stamped and frozen upon faces still in death, lay the remains of the New York producer. Save for a small bruise on one cheekbone the body appeared quite normal. A serene expression was on his face, in strange comparison with the distorted countenances of others about him." |

|||

The body was taken to an official morgue for embalming. His death notice, published in newspapers on the morning of his funeral, Tuesday, May 25, asked that flowers be omitted and made no reference to the Lusitania, simply stating that he had perished on May 7 “on the high seas.” A private funeral service for family members only began at [[Daniel Frohman]]’s home in New York at 10:00 a.m., with the public service at the Emanu-El Temple. [[Augustus Thomas]] delivered the funeral oration. Among the pallbearers were Thomas, [[George Ade]], [[Edward Sheldon]], [[Richard Harding Davis]], [[E. H. Sothern]], [[William Gillette]], [[Otis Skinner]], [[William Faversham]] and [[David Belasco]].” |

|||

Along with the service in New York, however, there were services in Los Angeles (arranged by [[Maude Adams]]), San Francisco (arranged by [[John Drew]]), Tacoma (arranged by [[Billie Burke]]), and Providence (arranged by members of the Julia Sanderson-Donald Brian-Joseph Cawthrone company). A memorial service was also held in London at the Church of St.-Martins-in-the-Fields with the Reverend W. P. Beasley, sub-Dean of St. Paul’s, giving the address. Frohman was also eulogized by the French Academy of Authors in Paris. There were no performances by any of Frohman’s companies the night of the funeral, and Frohman’s Empire Theatre in New York was dark for the entire evening. |

|||

Throughout his career Frohman had issued such publications as "Charles Frohman Presents Maude Adams in Romeo and Juliet," and "Charles Frohman Presents William Gillette in Secret Service." Now, not only had he been gallant in the last moments of his life, but thousands were mourning his death in several major cities in America and Europe. Thus, his greatest production was his own death, and the greatest star created by this maker of stars was, in the end, the star-maker himself. "Forgotten was the picture of that ghastly last hour aboard the Lusitania," [[Otis Skinner]] concluded. "The real man who did not fear death because it was life's great adventure had gone one. 'Nothing in his life became him like the leaving it.' As the synagogue organ rumbled forth the Chopin funeral march we, who were bidding him God speed, walked with firmer tread. It was so supremely a great achievement which 'Charles Frohman Presents.'" |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||

The Charles Frohman legacy remains a mixed one in the eyes of many. Actress [[Billie Burke]] summed up his place in theatrical history: “He controlled an empire, producing both in London and in New York. He had virtually invented the star system. He had the most gifted and the most celebrated actors and actresses under contract to him, including [[Maude Adams]], who was making more money than any woman in the world had ever made on the stage. If his legs had been just a little longer, someone said, Frohman could have walked across America on the theaters he controlled.” |

|||

In looking at Frohman's impact, Gerald Bordman wrote in The ''Oxford Companion to American Theatre'', "(The stars') celebrity was important to Frohman, since he recognized that a star could attract audiences even when his or her vehicle was weak, while a fine play without a star often had to struggle for business. Detractors have suggested that, as a result of this thinking, Frohman cared little about the value of his plays, ignoring promising American playwrights and preferring to buy up wholesale the rights to tested European works. Moreover, they add, his policy destroyed the interest in classics that his predecessors such as the Wallacks and Augustin Daly had carefully nurtured. While all this remains correct, especially his preoccupation with modern plays, it remains equally important to note that not all the plays Frohman offered were merely effective but ephemeral theatre pieces. He was responsible for the American premieres of many works by such significant and durable playwrights as [[Oscar Wilde]], [[Sir James Barrie]], [[Arthur Wing Pinero]], [[Somerset Maugham]], and [[Georges Feydeau]]. Among plays given their American premieres by Frohman were ''The Importance of Being Earnest'' (1895), ''The Girl from Maxim's'' (1899), ''Peter Pan'' (1905), ''Alice Sit-by-the-Fire'' (1905), and ''What Every Woman Knows'' (1908). Nor did he totally neglect the best American talent, producing several of [[Clyde Fitch]]'s plays, including ''[[Barbara Frietchie]]'' (1899). Moreover, he promoted an international respect for rising American playwrights by presenting their works abroad even when he had not produced the original New York mountings." |

|||

And [[Brooks Atkinson]] maintained, “He illustrates one of the most winning aspects of the theater – it can transform the people who go into it. In the case of Charles Frohman, it transformed an eight-year-old boy who sold souvenir programs for ''The Black Crook'' into the foremost producer of his time, the friend and manager of most of the contemporary stars and a man who met death with a cavalier gallantry that still seems remarkable.” |

|||

Some criticized Frohman's commercial methods. This has been a continuous criticism. Artistic snobs are always critical of the commercial, as if real art is never done for money but, rather, for the pure “love of the art” while the artist starves. [[Archie Binns]] pointed out that "Early in the nineteen-hundreds, sensibilities were shocked when Charles Frohman boasted that he ran his theatres like department stores, and referred to the theatres of America as ‘my colossal business enterprise.’ By the time producers spoke of themselves as the ‘motion-picture industry,’ the public had forgotten that the theatre could be anything but an industry." |

|||

Frohman had brought order and efficiency to what had been chaos. Maude Adams explained, “Under Mr. Frohman’s leadership the theatre, from being a fly-by-night hazard, became a great industry, respected and counted upon. The Syndicate which Mr. Frohman was greatly instrumental in starting and maintaining showed what an economic factor the theatre can be in a country such as ours, with important cities from one end of the continent to the other. It supplied widely spread employment in many trades. One might say the principles of mass production lend themselves to a nationwide theatre.” |

|||

Yet, it was because he was commercial that Frohman was able to deliver theatre entertainment of the highest quality. The criticism that theater managers should not be commercial was unfair and unfounded. In a speech before the Theatre Managers Association in 1910, [[William Gillette]] satirized the general attitude toward theater managers being commercial: “All the people in any other kind of business or profession or pursuit, all proprietors of stores who sell provisions and works of art, all newspapers, all book publishers, and music publishers and opera managers and poets and artists and critics are struggling like hell to give the people what they want. But you mustn’t do that! You are the only thing on God’s earth who mustn’t be commercial.” |

|||

[[E. H. Sothern]] commented: “This abuse is quite nonsensical and unfair. The amusement-loving public demands many kinds of entertainment. It can be said of Charles Frohman that he never on any single occasion offered anything below the standard of cleanliness and good manners, and that, on the other hand, he provided his patrons with the very best plays by the very best dramatists of his time, interpreted by the most capable actors procurable. The salaries of players and the royalties of playwrights increased by leaps and bounds under his generous direction, for he was ever ready to pay for the best. Masterpieces are not written frequently; if Mr. Frohman overlooked any in his generation they are yet to be discovered. |

|||

“A recent play contest offering a prize of ten thousand dollars succeeded no better than previous occasions of the same nature in unearthing neglected genius. Nor did the generous experiment of the New Theatre, nor any of the several excursions of the dissatisfied and inspired display one actor or play superior to those produced by the commercial managers. |

|||

“We are informed that the theatre has great power along lines of instruction and reform, but it is observed that philanthropists do not endow playhouses. |

|||

“Sir Henry Irving’s oft-quoted axiom that the theatre ‘must succeed as a business or it will fail as an art’ is no more than plain common sense, and the frothing and foaming of all the ink-pots in the world will not make it otherwise. |

|||

“When Haroun-al-Raschid desired to learn how he should govern his kingdom, he went disguised into the taverns, and there the toss-pots instructed him; for the failures in life can always advise the successful ones as to the conduct of their affairs. |

|||

“Charles Frohman, no doubt, lost much wisdom by not hearkening to the wine-bibbers. They, on the other hand, would have had lighter hearts, heavier pockets, and happier heads had they denounced him less and spent the time thus gained in emulation of his honesty, good humor, kindliness, industry, and courage.” |

|||

Also criticized was Frohman's partnership in the Theatrical Syndicate. Yet, as Goldman noted, "The lively opposition that had developed from the Syndicate's foes brought forth scornful comment from members of the so-called Trust but only expressions of considerable admiration from Charles Frohman, then becoming the outstanding figure in the New York theatre. He was a passive member of the combination. The Syndicate needed Frohman's name; he needed its money. He frequently remarked that all he ever got from his participation was trouble." |

|||

With financial backing from a Syracuse haberdasher, the Shubert Brothers came to the big city deliberately to take on the Trust. Thus began a bitter war that would consume both sides – and the theater with it – for the next fifteen years. But, as crooked as the Trust had been, the Shuberts themselves soon behaved no better than their rivals. To fight the Syndicate, they built too many theaters across the country. It got more and more bitter as newspapers began referring to the “two syndicates” and bestowed the same printed abuse on the Shuberts as they had on the original Trust. Archie Binns, [[Minnie maddern Fiske]]’s biographer, noted, "The original avowed aim of the Syndicate had been to end the duplication of booking agencies – and the final result was a ruinous duplication of theatres. Out of disorder it brought anarchy." |

|||

Without question, the fruit of the efforts of the Syndicate was the decline of the American Theatre. [[William A. Brady]], theatrical genius and manager of boxing champion and actor [[James J. Corbett]], later recalled, "People lamenting the well-known ‘decline of the American theater’ give you every reason for it, from the introduction of coeducational drinking to the periodic recurrence of sun-spots. As one who saw the syndicate rise and fall and fought it every step of the way, I can tell you that its injection of big business into the theatrical game had more to do with the decline of the American theater than any other ten things you can imagine." |

|||

And [[Archie Binns]] concluded, "The Syndicate declined, but Charles Frohman’s methods lived after him, through the Shuberts, in the declining theatre; and they were to serve as the blueprint for motion pictures which replaced the legitimate theatre." |

|||

A man with little education and no great artistic interests, he was nevertheless gifted with an uncanny perception of what would go over with audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. Of course, he was no romanticist at the cash register, pursuing worldly and monetary success with the same zeal as a champion athlete or corporate ladder-climber, and he achieved both beyond his wildest dreams. But, to achieve the success he craved, Frohman had to deal in personalities, which he cultivated and on which he thrived. |

|||

Frohman, however, is best remembered for something else, something better than mere theiatrical success: his personal integrity. Simply put, he never broke his word, and everybody who dealt with him testified to that. [[E. H. Sothern]] remarked, “The Frohman word was as good as a bond to any man. This was Charles Frohman’s especial pride.” [[John Drew]] had left the management of [[Augustin Daly]] to join Frohman's stable, and he later wrote, "I never had cause to regret my change in management. Charles Frohman was one of the fairest and squarest men I ever met." St. John Erving, in his biography of [[George Bernard Shaw]], wrote that "Frohman was a man of such honesty of character that no one who worked with him had a contract. His word was enough for everybody." To this, [[James Barrie]] added, "There was a great deal more to him, but every one in any land who has had dealings with Charles Frohman will sign that.” |

|||

He did not believe in written contracts and, when someone urged him to make them, he replied, “No, I won’t do it. I want them to be in a position so that if they ever become dissatisfied they know they are free to leave me." Few ever did. Among the very few signed contracts Frohman had was with Drew, when Drew first joined him. After that, his only contract was his word. And, while negotiations with Frohman often involved hundreds of thousands of dollars, it was all any actor or actress ever needed. Channing Pollock once presented Frohman with an idea for a play, and Daniel Frohman later handed him half a sheet of note paper on which Frohman had scrawled, "I agree to produce your play when we’re both ready, and to pay usual royalties. C.F." And Channing Pollock recalled, “The play was not otherwise described, and the agreement was not dated. Frohman’s word was as good as his bond, and everyone knew it.” |

|||

Most of all, Charles Frohman exhibited that in-born love for, and fascination with, the theatre. He was a dreamer, a man who followed his artistic instincts and reveled in the theatrical art he created. “Having seen the theatre,” [[James Barrie]] wrote, “he never saw anything else.” And Allen Churchill, in The Great White Way, added, “For Charles Frohman was another of those fortunate boys – there seemed to be many at the time! – who on first viewing a theatre performance found the world of make-believe forever superior. On learning that it was possible to make money in this bright new wonderland, Frohman (no less than Belasco and others) never considered devoting his energies to anything else. He remained stage-struck all his life. To him the playhouse was the real universe; outside, all was wearying and bothersome.” |

|||

This was demonstrated, perhaps most of all but tragically as well, in his estate at the time of his death. The man who possessed a total lack of financial concern, in an industry that thrived on greed, became notorious only when it was discovered that his entire net estate totaled $451.76. On his meager estate, [[Brooks Atkinson]] commented, “This tiny estate is significant: as a businessman, he could have looked after his affairs more successfully if making money were his first consideration.” |

|||

And [[Montrose Moses]] added, “He died poor, and everything he earned went back into the theatre which gave it to him. He was a child in the pleasure he took in theatre management. But, in order to play, he must have money to play with, and so he trimmed his sails to the box-office gale; public approval was the wind by which he steered. If he foundered, he took to another vessel and did not bemoan his loss, except in so far as it might limit his plans for further adventure.” |

|||

Frohman dominated the American and British theater during its most expansive years. He took over a haphazard circus and turned it into a well-organized enterprise. He produced many of the era’s outstanding plays and managed its greatest stars. Yet, when he was once asked what he would like to be remembered for, he didn’t hesitate: “All I would ask is this: ‘He gave Peter Pan to the world.’ It is enough for any man.” |

|||

In an era when the theatrical world was far more colorful and diverse than it is today – it was, in fact, the early era’s version of today’s world of motion picture industry – Charles Frohman was among the most colorful characters of them all. |

|||

==Popular Culture== |

|||

Charles Frohman has been featured, to some degree, in three motion pictures. Jolivet, who alone of that last-minute foursome survived the [[Lusitania]] disaster, starred in the silent film, ''Lest We Forget'', starring herself in the melodramatic starring role. A news report revealed that many of the scenes were filmed in a French village set constructed in Westchester County, New York, and the film was to immortalize Frohman’s last words, even though Frohman himself was not a credited character in the film. It was released by the Rita Jolivet Film Corporation on January 28, 1918. |

|||

The magnate got a speaking part in the 1946 MGM musical production, ''[[Till the Clouds Roll By]]'', one of the big box office hits of the year but a typical Hollywood biopic of composer [[Jerome Kern]] (portrayed by [[Robert Walker]]) and featuring twenty-two of Kern’s best compositions throughout. The film featured [[Judy Garland]] as [[Marilyn Miller]], [[Paul Maxey]] as [[Victor Herbert]], [[Van Heflin]] as [[James I. Hessler]], and [[Paul Langton]] as [[Oscar Hammerstein]]. Frohman was portrayed by character actor [[Harry Hayden]], who usually played banker or businessman type roles in a number of films between 1937 and 1947, and whose best role may have been as the grouchy father to [[June Allison]] and [[Kathryn Grayson]] in ''Two Sisters from Boston''. |

|||

Finally, Frohman appeared before modern audiences in the 2004 Miramax film, ''[[Finding Neverland]]'', directed by [[Marc Forster]] and starring [[Dustin Hoffman]] as an amiable but fussy Frohman with [[Johnny Depp]] as [[James Barrie]], [[Kate Winslet]] as [[Sylvia Llewelyn Davies]], [[Julie Christie]] as [[Emma du Maurier]], [[Ian Hart]] as [[Sir Arthur Conan Doyle]], [[Radha Mitchell]] as [[Mary Barrie]], and [[Kelly Macdonald]] as [[Peter Pan]]. Based on the play ''The Man Who Was Peter Pan'' by [[Allen Knee]], ''[[Finding Neverland]]'' was filmed in England and released in October 2004. and was in theaters through February 2005. The setting is London, beginning with the flop of Barrie’s ''Little Mary'' in 1903, and continuing in 1904 as Barrie becomes close to the Davies family and struggles to bring ''[[Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up]]'' to the stage. |

|||

==Quotes== |

|||

By 1915 Frohman had produced more than 700 shows, employed an average of 700 actors per season, and paid salaries totalling $25,000 a week. Frohman controlled five theaters in London, six in New York City, and over two hundred throughout the rest of the United States. |

|||

* Madam, your secret is safe with me. (To Mrs. Patrick Campbell) |

|||

Frohman died in the 1915 sinking of the [[RMS Lusitania]] by the [[Germany|German]] [[u-boat|submarine]], [[Unterseeboot 20]]. Songwriter [[Jerome Kern]] was meant to accompany him on the voyage, but overslept after being kept up late playing requests at a party. Frohman was reported by survivors to have declined a seat on a lifeboat, saying "Why fear death? It is the greatest adventure in life," echoing a famous line from ''Peter Pan''. Frohman's body was recovered and brought back to the United States for burial in the Union Field Cemetery in [[Ridgewood, New York]]. |

|||

* I greatly appreciate the offer, but I don’t care to manage Olcott. He is made. I like to make stars. (Upon Chauncey Olcott’s request that Frohman become his manager) |

|||

* This little ship you sent is more wonderful than the big one that takes me away from you. |

|||

* When you consider all the stars I have managed, mere submarines make me smile. |

|||

* I don’t read the news. I ''make'' news. |

|||

* I’m only afraid of the IOUs (When asked if he was afraid of the U-Boats) |

|||

* Why fear death? It is the most beautiful adventure in life. |

|||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

* Hollis Alpert, ''The Barrymores'' (The Dial Press, 1964). |

|||

* [[Isaac Frederick Marcosson]] with [[Daniel Frohman]], ''Charles Frohman, Manager and Man'', (1917) |

|||

* John Anderson, ''The American Theatre'' (The Dial Press, 1938). |

|||

* Brooks Atkinson, ''Broadway'' (The MacMillan Company, 1970). |

|||

* Thomas A. Bailey & Paul B. Ryan, ''The Lusitania Disaster'' (The Free Press, 1975). |

|||

* Ethel Barrymore, ''Memories: An Autobiography'' (Harper & Brothers, 1955). |

|||

* Lionel Barrymore, ''We Barrymores, The life story of a fabulous member of a fabulous family'' (Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1951). |

|||

* Archie Binns, ''Mrs. Fiske and the American Theatre'' (Crown Publishers, Inc., 1955). |

|||

* Gerald Bordman, ''The Concise Oxford Companion to American Theatre'' (Oxford University Press, 1984). |

|||

* Billie Burke, ''With a Feather on My Nose'' (Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1949). |

|||

* Allen Churchill, ''The Great White Way'' (E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1962). |

|||

* John Drew, ''My Years on the Stage'' (E. P. Dutton & Company, 1922). |

|||

* Janet Dunbar, ''J. M. Barrie, The Man Behind the Image'' (Houghton, Mifflin Company, 1970). |

|||

* Daniel Frohman, & Isaac F. Marcosson, ''Charles Frohman'' (John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1916). |

|||

* Daniel Frohman, ''Daniel Frohman Presents, An Autobiography'' (Claude Kendall & Willoughby Sharp, 1935). |

|||

* Daniel Frohman, ''Encore'' (Lee Furman, Inc., 1937). |

|||

* Des Hickey & Gus Smith, ''Seven Days to Disaster, The Sinking of the Lusitania'' (G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1981). |

|||

* Foster Hirsch, ''The Boys From Syracuse'' (Southern Illinois University Press, 1998). |

|||

* Glenn Hughes, ''A History of the American Theatre 1700-1950'' (Samuel French, 1951). |

|||

* James Kotsilibas-Davis, ''Great Times, Good Times, The Odyssey of Maurice Barrymore'' (Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1977). |

|||

* Percy MacKaye, ''Epoch: The Life of Steele MacKaye'' (Boni & Liveright, 1927). |

|||

* Lise-Lone Marker, ''David Belasco: Naturalism in the American Theatre'' (Princeton University Press, 1974). |

|||

* Ward Morehouse, ''Matinee Tomorrow, Fifty Years of Our Theater'' (Whittlesey House, 1949). |

|||

* Montrose J. Moses, ''The American Dramatist'' (Little, Brown, and Company, 1925). |

|||

* Ada Patterson, ''Maude Adams, A Biography'' (Meyer Bros. & Co., 1907). |

|||

* John Perry, ''James A. Herne: the American Ibsen'' (Nelson-Hall, 1978). |

|||

* Channing Pollock, ''Harvest of My Years'' (The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1943). |

|||

* Margot Peters, ''Mrs. Pat, The Life of Mrs. Patrick Campbell'' (Alfred A. Knopf, 1984). |

|||

* Diana Preston, ''Lusitania, An Epic Tragedy'' (Berkley Trade Paperback edition, Berkley Publishing Group, 2002). |

|||

* Phyllis Robbins, ''Maude Adams, An Intimate Portrait'' (G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1956) |

|||

* Phyllis Robbins, ''The Young Maude Adams'' (Marshall Johns Company, 1959). |

|||

* Colin Simpson, ''The Lusitania'' (Little, Brown and Company, 1972). |

|||

* Otis Skinner, ''Footlights and Spotlights'' (Blue Ribbon Books, 1924). |

|||

* E. H. Sothern, ''The Melancholy Tale of "Me", My Remembrances'' (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916). |

|||

* Jerry Stagg, ''The Brothers Shubert'' (Random House, 1968). |

|||

* Craig Timberlake, ''The Bishop of Broadway'' (Library Publishers, 1954). |

|||

* William Winter, ''The Life of David Belasco'', 2 Vol., (Moffat, Yard and Company, 1918). |

|||

* Henry Zecher, ''The Masque of Sherlock Holmes, the Extraordinary Life of William Gillette'', to be published soon. |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Revision as of 04:03, 14 October 2007

Charles Frohman (July 15 1856 – May 7, 1915) was an American theatrical producer.

One of the three famous Frohman brothers. Sons of a German-Jewish cigar-maker and aspiring actor who had immigrated from Darmstadt, in the Rhein-Main region of Germany, the brothers were born in Sandusky, Ohio: Daniel in 1851; Gustave in 1854; and Charles in 1856. The year of Charles' birth date is generally erroneously reported as 1860, and his birthday is shown as July 16 on his tombstone, but the correct date is July 15, 1856 (sources: Certified Birth Certificate, Sandusky, Ohio and the 1860 Federal Census for Sandusky, Ohio, which shows: "Charley," age 4).

He was the greatest theatrical manager and producer of his era, and his “Frohmannational Theatricalities” ran from coast to coast and continent to continent. The theater’s dominant figure for more than a quarter of a century, Frohman was short and rotund, and he literally waddled when he walked. Lloyd Morris in Curtain Time described him as “Squat, bald, sallow-faced, his large, melting eyes alone redeemed him from ugliness.” He was called many names – not all of them complimentary – including the “Beaming Buddha,” "the Little Napoleon of the Theater," and head of the "Holy Frohman Empire." His friends called him simply "C.F."

Whereas the theater of the melodramatic era had been a loosely-knit community of independent theaters, with actors and actresses basically managing themselves, the new era of big business demanded that performers procure the services of a personal manager and either sign contracts with an all-controlling theater syndicate, or be left out in the cold with no where to work. By the 1880s the Frohman Brothers had become the leading theatrical managers and producers in New York City.

American drama was at its lowest point when the Frohmans came along but, by importing the best foreign playwrights and developing the star system, they took a fairly informal and scattered profession and turned it into a highly profitable enterprise. Although they were criticized for doing little to encourage native playwrights, they gave the theater an entirely new direction, as well as an aura of dignity and respectability. Charles Frohman's plays were based on romance, sentiment, and light comedy. He abhorred death scenes and eschewed indecency. And, he created the “Star” system which revolutionized the theater and is still with us today.

Life and career

In 1864, Frohman's family moved to New York City, where Frohman eventually worked for a newspaper. In New York, Frohman developed a love of the theatre that led to him becoming a booking agent and then working his way up to producer and theatre owner/operator.

When Charles became an independent manager in 1883, he launched – as his first production – David Belasco’s The Strangers of Paris at the New York Theatre. He lost money on the deal; but that wasn’t important. Charles Frohman, at 23 years of age, had produced his first play, and nothing could have made him happier.

Two more shows failed, and then he produced Caprice with Henry Miller. For Miller’s leading lady, Frohman chose the young Minnie Maddern. Caprice was a hit, and it made her a star. He put five plays on Broadway in 1886, and two in 1887, including She, a romantic adventure story adapted by William Gillette from Rider Haggard’s novel of the same name, which opened to great acclaim at Niblo’s Garden in New York on November 29.

But, up to this time, Frohman had not scored the smashing success he needed to make his name and fortune. Then, in early 1889 he found his audience with Bronson Howard's Shenandoah. After Shenandoah put him on top, Frohman opened his opulent office at 1127 Broadway; there he began hatching his legendary successes. In 1890 he leased Proctor’s Twenty-third Street Theatre and established the Charles Frohman Stock Company. After mounting Gillette’s The Private Secretary at the Grand Opera House on August 26, he launched Gillette’s All the Comforts of Home at Proctor's on September 8, starring Henry Miller and introducing to new acclaim a delicate and elfin young actress named Maude Adams.

In 1893 he produced his first Broadway play Clyde Fitch's Masked Ball. This play marked the first time that actress Maude Adams played opposite John Drew, which led to many future successes. Soon he acquired five other New York City theaters.

On January 25, 1893, he opened his fabulous Empire Theatre on the corner of Broadway and 40th Street, near the Metropolitan Opera House, then only ten years old. It was not an auspicious location, sitting as it did so far from the center of the Union Square Theatre District and bordering on the city’s notorious red light district, called the Tenderloin. It also sat a mere two blocks from Longacre Square, an unlit intersection in midtown Manhattan at 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue popularly called the Thieves’ Lair because of its rollicking forms of low entertainment and its correspondingly high level of crime. The Broadway Theater was the only other uptown theater at the time.

All of this, of course, was no cause for concern for the man who never worried to begin with; he would simply make his productions so irresistible that people would cross mighty oceans and burning deserts to see them, not to mention of few extra blocks in Manhattan. In fact, along with playgoers, other producers would build their theaters to the vicinity of the Empire, thus establishing a new theatrical district in New York. This became the heart of the Broadway theater district and pushed the northern edge of the Rialto to the southern border of the Thieves’ Lair, which later obtained half the world’s share of electric lighting and, in 1904 by proclamation of Mayor George B. McClellan, Jr. (the general’s son), was renamed Times Square.

Frohman had always been one to see value in big names. In his era, the star carried the play, rather than the reverse. The problem under the old system was that performers became "stars" only after having paid their dues and climbing through the ranks. It was a long and tedious process for which Frohman had neither time nor patience. He needed stars to put his plays across and, if he intended to make rather than acquire them, then he had to work quickly and focus his attention on the actors in his charge. Comparing a play to a dinner, he said, "To be a success, no matter how splendidly served, the menu should always have one unique and striking dish that, despite its elaborate gastronomic surroundings, must long be remembered."

Thus, he became known for his ability to develop talent. Rather than take on established stars, he took unknowns and made them into stars. The only established stars he signed up -- by way of launching his empire -- were John Drew and William Gillette, but those he made into stars included Billie Burke. Nat Goodwin, Elsie De Wolfe, Arthur Bryon, Edna May, Annie Russell, Margaret Anglin, Marie Tempest, E. H. Sothern, Otis Skinner, Julia Marlowe, Seymour Hicks, Marie Doro, Henry Miller, Arnold Daly, and the entire Barrymore family – Maurice Barrymore and his three offspring John Barrymore, Ethel Barrymore, and Lionel Barrymore. As a producer, he produced the works of George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, James M. Barrie, Haddon Chambers, Henry de Mille, John Galsworthy, Alfred Sutro, and Harly Granville-Barker. He also produced all of Somerset Maugham's plays in the United States, most of them successfully, and was responsible for Maugham’s great popularity in America.

In 1897, Frohman leased the Duke of York's Theatre in London, introducing plays there as well as in the United States. Clyde Fitch, J. M. Barrie, and Edmond Rostand were among the playwrights he promoted. As a producer, among Frohman's most famous successes were Barrie's Peter Pan with Maude Adams and William Gillette's Sherlock Holmes starring Gillette himself in his most celebrated role. In the early years of the 20th century, Frohman also established a successful partnership with Seymour Hicks to produce musicals and other comedies in London, including Quality Street in 1902, The Admirable Crichton in 1903, The Catch of the Season in 1904, The Beauty of Bath in 1906, The Gay Gordons in 1907, and A Waltz Dream in 1908, among others. He also partnered with other London theatre managers. The system of exchange of successful plays between London and New York was largely a result of his efforts. In 1910, Frohman attempted a repertory scheme of producing plays at the Duke of York's. He advertised a bill of plays by J. M. Barrie, John Galsworthy, Harley Granville Barker, and others. The venture began tentatively, and while it may have proved successful, Frohman canceled the scheme when London theatres closed at the death of King Edward VII in February 1910.

Frohman was the first manager to distribute what would later be called "press releases," sending to the newspapers stylographic press sheets containing news of his many attractions. And he employed delicate touches to celebrate his successes. On the night of the 300th performance of Barrie’s The Little Minister, which starred Maude Adams, Frohman gave an American Beauty rose, complete with the necessary pin, to every woman in the audience. Another of his theatrical “firsts” was to order a private railroad car in 1890 for the entire touring company of Men and Women. Many considered it extravagant, but Frohman wanted his people to be comfortable.

Frohman controlled five theaters in London, six in New York City, and over two hundred more throughout the rest of the United States. By 1915, he had produced more than 700 shows, managed 28 bonafide stars at one time, employed about 10,000 people on his payroll – 700 of them actors – and paid salaries totaling $35 million a year. He controlled six theaters in New York, more than 200 throughout the country, and six more in London. In 1904 alone he had ten plays running in London at the same time. Actors on both sides of the Atlantic vied for his managerial genius, and many appeared on stages in both England and the United States. As the saying went, "Frohman takes America to England and brings England back to America."

The Theatrical Syndicate

In 1896, Frohman, Al Hayman, Abe Erlanger, Mark Klaw, Samuel F. Nixon, and Fred Zimmerman formed the Theatrical Syndicate, which owned or controlled many theaters throughout the United States. It had been formed in secret, in the Holland House, by Frohman, Marc Klaw, Al Hayman, Abraham Lincoln Erlinger, Samuel F. Nirdlinger, and J. Frederick Zimmerman. The six conspirators signed on August 31 the Syndicate Agreement which cited the problems with the current booking system and proposed the formation of this syndicate as the remedy for those problems. They felt that the only solution to the chaos of the theatrical world was centralized booking. Through the auspices of the Syndicate, cross-country bookings became standardized. Without any great expense, a troupe manager could book an entire tour. Conflicting engagements were eliminated, as well as the booking of two major productions in the same town at the same time. The new Syndicate established systemized booking networks throughout the United States and created a monopoly that controlled every aspect of contracts and bookings.

What precisely Frohman's role was in the Theatrical Syndicate remains a matter of dispute. For one thing, he already had a kingdom of his own and didn't need them as much as they needed him. "His supporters," Gerald Bordman explained, "have claimed that he was the idealist in the group, looking the other way at its shady practices because he felt more benefits than harm came from its methods. Others have seen him as playing Spenlow to Erlanger's Jorkins. Most likely the truth lies somewhere in between. But the certainty of comfortable bookings allowed him to work with ease, develop a roster of great stars, and present a steady stream of popular plays."