Oeselians: Difference between revisions

m r2.7.2+) (Robot: Adding sh:Saarlased |

autonym and IPA pronunciation |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{History of Estonia}} |

{{History of Estonia}} |

||

The '''Oeselians''' |

The '''Oeselians''' or '''Osilians''' ([[Estonian language|Estonian]] ''saarlased'' ({{IPA-fi|ˈsɑːrlɑset|et}}); singular: ''saarlane'') were a historical subdivision of [[Estonian]]s inhabiting [[Saaremaa]] ({{lang-la|Oesel}} or {{lang|la|''Osilia''}}), an [[Estonia]]n island in the [[Baltic Sea]]. They are first thought to be mentioned as early as the 2nd century BC in [[Ptolemy|Ptolemy's]] ''Geography III''.<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=4BxvGd3c9OYC&pg A History of Pagan Europe By Prudence Jones, Nigel Pennick; p.195] ISBN 0-415-09136-5</ref> [[File:Europe 814.jpg|thumb|300px|Europe in 9th century]] The Oeselians were known in the [[Old Norse]] [[Icelandic Sagas]] and in [[Heimskringla]] as ''Víkingr frá Esthland'' ({{lang-en|Estonian Vikings}}).<ref name="OTS">{{no icon}}[http://www.skole.karmoy.kommune.no/wavald/sagaoya/snorre/olav%20trygvasson.html Olav Trygvassons saga at School of Avaldsnes]</ref><ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=ZTVjwf2ZPGYC&pg Heimskringla; Kessinger Publishing (March 31, 2004); on Page 116;] ISBN 0-7661-8693-8</ref><ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=4BxvGd3c9OYC&pg=PA166&vq=%22Estonian+Vikings%22&sig=gWbLLsPmTPloyTpG4HdpqIS7FYk A History of Pagan Europe by Prudence Jones; on page 166;] ISBN 0-415-09136-5</ref><ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=g2-Lga0r62MC&pg=PA177&vq=Estonian+Vikings&sig=rw28BfteCrHXhnTn7l_p-875vu4 Nordic Religions in the Viking Age by Thomas A. Dubois; on page 177;] ISBN 0-8122-1714-4</ref> Their sailing vessels were called pirate ships by [[Henry of Livonia]] in his Latin chronicles from the beginning of the 13th century.<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=FmJnyTlis7oC&printsec The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia] ISBN 0-231-12889-4</ref> |

||

''Eistland'' or ''Esthland'' is the historical Germanic language name that refers to the country at the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea in general, and is the origin of the modern national name for Estonia. The mainland of modern Estonia in the 8th century [[Ynglinga saga]] was called ''Adalsyssla'' in contrast to ''Eysyssel'' or ''Ösyssla'' that was the name of the island ({{lang-sv|Ösel}}, {{lang-et|[[Saaremaa]]}}), the home of the Oeselians ({{lang-et|Saarlased}}). In the 11th century [[Courland]] and Estland (Estonia) were both denoted separately by [[Adam of Bremen]].<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=QsS-fAVrUgIC&pg=PA196&vq History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen By Adam of Bremen Page 196-197]</ref> |

''Eistland'' or ''Esthland'' is the historical Germanic language name that refers to the country at the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea in general, and is the origin of the modern national name for Estonia. The mainland of modern Estonia in the 8th century [[Ynglinga saga]] was called ''Adalsyssla'' in contrast to ''Eysyssel'' or ''Ösyssla'' that was the name of the island ({{lang-sv|Ösel}}, {{lang-et|[[Saaremaa]]}}), the home of the Oeselians ({{lang-et|Saarlased}}). In the 11th century [[Courland]] and Estland (Estonia) were both denoted separately by [[Adam of Bremen]].<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=QsS-fAVrUgIC&pg=PA196&vq History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen By Adam of Bremen Page 196-197]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:10, 6 May 2012

| History of Estonia |

|---|

|

| Chronology |

|

|

The Oeselians or Osilians (Estonian saarlased (Finnish pronunciation: [ˈsɑːrlɑset]); singular: saarlane) were a historical subdivision of Estonians inhabiting Saaremaa (Latin: Oesel or [Osilia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), an Estonian island in the Baltic Sea. They are first thought to be mentioned as early as the 2nd century BC in Ptolemy's Geography III.[1]

The Oeselians were known in the Old Norse Icelandic Sagas and in Heimskringla as Víkingr frá Esthland (English: Estonian Vikings).[2][3][4][5] Their sailing vessels were called pirate ships by Henry of Livonia in his Latin chronicles from the beginning of the 13th century.[6]

Eistland or Esthland is the historical Germanic language name that refers to the country at the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea in general, and is the origin of the modern national name for Estonia. The mainland of modern Estonia in the 8th century Ynglinga saga was called Adalsyssla in contrast to Eysyssel or Ösyssla that was the name of the island (Swedish: Ösel, Estonian: Saaremaa), the home of the Oeselians (Estonian: Saarlased). In the 11th century Courland and Estland (Estonia) were both denoted separately by Adam of Bremen.[7]

On the eve of Northern Crusades, the Oeselians were summarized in the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle thus: "The Oeselians, neighbors to the Kurs (Curonians), are surrounded by the sea and never fear strong armies as their strength is in their ships. In summers when they can travel across the sea they oppress the surrounding lands by raiding both Christians and pagans." [8]

Battles and raids

Saxo Grammaticus describes the Curonians and Estonians as participating in the Battle of Bråvalla on the side of the Swedes against the Danes, who were aided by the Livonians and the Wends of Pomerania. It is notable that other Baltic tribes — i.e., the Letts and Lithuanians — are not mentioned by Saxo as participating in the fight.[9] Snorri Sturluson relates in his Ynglinga saga how the Swedish king Ingvar (7th century), the son of Östen and a great warrior, who was forced to patrol the shores of his kingdom fighting Estonian vikings. The saga speaks of his invasion of Estonia where he fell in a battle against the men of Estland who had come down with a great army. After the battle, King Ingvar was buried close to the seashore in Estonia and the Swedes returned home.[10]

According to Heimskringla sagas, in the year 967 the Norwegian Queen Astrid escaped with her son, later king of Norway Olaf Tryggvason from her homeland to Novgorod, where her brother Sigurd held an honoured position at the court of Prince Vladimir. On their journey, Oeselian Vikings raided the ship, killing some of the crew and taking others into slavery. Six years later, when Sigurd Eirikson traveled to Estonia to collect taxes on behalf of Valdemar, he spotted Olaf in a market on Saaremaa and paid for his freedom.

A battle between Oeselian and Icelandic Vikings off Saaremaa is described in Njál's saga as occurring in 972 AD.

About 1008, Olaf the Holy, later king of Norway, landed on Saaremaa. The Oeselians, taken by surprise, had at first tried to negotiate the demands made by the Norwegians, but then gathered an army and confronted them. Nevertheless Olaf (then 13 years old) is reputed to have won the battle. Olaf was the subject of several biographies, both hagiographies and sagas, in the Middle Ages, and many of the historical facts concerning his adventures are disputed.

Around the year 1030, a Swedish Viking chief called Freygeirr may have been killed in a battle on Saaremaa.

According to the Novgorod Chronicle, Varyag Ulf (Uleb) from Novgorod was crushed by Estonians in a sea battle close to the town of Lindanise in 1032.

From the 12th century, chroniclers' descriptions of Estonian, Oeselian and Curonian raids along the coasts of Sweden and Denmark become more frequent.

The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia describes a fleet of sixteen ships and five hundred Oeselians ravaging the area that is now southern Sweden, then belonging to Denmark. In the XIVth book of Gesta Danorum, Saxo Grammaticus describes a battle on Öland in 1170 in which the Danish king Valdemar I mobilised his entire fleet to curb the incursions of Couronian and Estonian pirates.

Perhaps the most renowned raid by Oeselian pirates occurred in 1187, with the attack on the Swedish town of Sigtuna by Finnic raiders from Couronia and Oesel. Among the casualties of this raid was the Swedish archbishop Johannes. The city remained occupied for some time, contributing to the decline as a center of commerce in the 13th century in favor of Uppsala, Visby, Kalmar and Stockholm.[12]

The Livonian Chronicle describes the Oeselians as using two kinds of ships, the piratica and the liburna. The former was a warship, the latter mainly a merchant ship. A piratica could carry approximately 30 men and had a high prow shaped like a dragon or a snakehead as well as a quadrangular sail.

Viking-age treasures from Estonia mostly contain silver coins and bars. Compared to its close neighbors, Saaremaa has the richest finds of Viking treasures after Gotland in Sweden. This strongly suggests that Estonia was an important transit country during the Viking era.

Religion and mythology

The superior god of Oeselians as described by Henry of Livonia was called Tharapita. According to the legend in the chronicle Tharapita was born on a forested mountain in Virumaa (Latin: Vironia), mainland Estonia from where he flew to Oesel , Saaremaa [13] The name Taarapita has been interpreted as "Taara, help!" (Taara a(v)ita in Estonian) or "Taara keeper" (Taara pidaja) Taara is associated with the Scandinavian god Thor. The story of Tharapita's or Taara's flight from Vironia to Saaremaa has been associated with a major meteor disaster estimated to have happened in 660 ± 85 B.C. that formed Kaali crater in Saaremaa.

Archeology

Estonia constitutes one of the richest territories in the Baltic for hoards from the 11th and the 12th centuries. The earliest coin hoards found in Estonia are Arabic Dirhams from the 8th century. The largest Viking-Age hoards found in Estonia have been at Maidla and Kose. Out of the 1500 coins published in catalogues, 1000 are Anglo-Saxon.[14]

Decline

With the rise of centralized authority along with a bolstering of coastal defense in the areas exposed to Vikings, Viking raids became more risky and less profitable. With the growing presence of Christianity and the rise of kings and a quasi-feudal system in Scandinavia, these raids ceased entirely. By the 11th century, the Scandinavians are frequently chronicled as clashing with the Vikings from the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, which would ultimately lead to German, Danish and Swedish participation in the Northern crusades and the Scandinavian conquest of Estonia.

The eastern Baltic world would be transformed by military conquest. First the Livs, Letts and Estonians, then the Prussians and the Finns were eventually overwhelmed and underwent baptism, military occupation and sometimes extermination by German, Danish and Swedish forces.[15]

Conquest of Oeselians

In 1206, the Danish army led by king Valdemar II and Andreas, the Bishop of Lund landed on Saaremaa and attempted to establish a stronghold without success. In 1216 the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and the bishop Theodorich joined forces and invaded Saaremaa over the frozen sea. In return the Oeselians raided the territories in Latvia that were under German rule the following spring . In 1220, the Swedish army led by king John I of Sweden and the bishop Karl of Linköping conquered Lihula in Rotalia in Western Estonia. Oeselians attacked the Swedish stronghold the same year, conquered it and killed the entire Swedish garrison including the Bishop of Linköping.

In 1222, the Danish king Valdemar II attempted the second conquest of Saaremaa, this time establishing a stone fortress housing a strong garrison. The Danish stronghold was besieged and surrendered within five days, the Danish garrison returned to Revel, leaving bishop Albert of Riga' brother Theodoric and few others behind hostages as pledges for peace. The castle was leveled to the ground by Oeselians.[16]

In 1227, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, the town of Riga and the Bishop of Riga organized combined attack against Saaremaa. After the surrender of 2 major Oeselian strongholds, Muhu and Valjala, the Oeselians formally accepted Christianity.

In 1236, after the defeat of the Livonian Brothers of the Sword in the Battle of Saule, military action on Saaremaa broke out again.

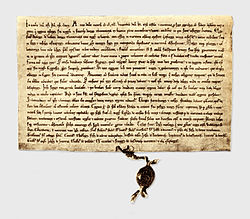

Oeselians accepted Christianity again by signing treaties with the Livonian Order's Master Andreas de Velven and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek in 1241. The next treaty was signed in 1255 by the Master of the Order, Anno Sangerhausenn, and, on behalf of the Oeselians, by elders whose "names" (or declaration?) had been phonetically transcribed by Latin scribes as Ylle, Culle, Enu, Muntelene, Tappete, Yalde, Melete, and Cake [17] The treaty granted several extraordinary rights to the Oeselians. The 1255 treaty included unique clauses concerning the ownership and inheritance of land, the social system, and exemption from certain restrictive religious observances.

In 1261, warfare continued as the Oeselians had again renounced Christianity and killed all the Germans on the island. A peace treaty was signed after the united forces of the Livonian Order, the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek, the forces of Danish Estonia including mainland Estonians and Latvians defeated the Oeselians by conquering the Kaarma stronghold. Soon thereafter, the Livonian Order established a stone fort at Pöide.

On 24 July 1343, during St. George's Night Uprising, the Oeselians killed all the Germans on the island, drowned all the clerics and started to besiege the Livonian Order's castle at Pöide. The Oeselians levelled the castle and killed all the defenders. In February 1344, Burchard von Dreileben led a campaign over the frozen sea to Saaremaa. The Oeselians' stronghold was conquered and their leader Vesse was hanged. In the early spring of 1345, the next campaign of the Livonian Order took place that ended with a treaty mentioned in the Chronicle of Hermann von Wartberge and the Novgorod First Chronicle. Saaremaa remained the vassal of the master of the Livonian Order, and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek. In 1559, after the fall of the Livonian order in Livonian War, the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek sold Saaremaa to Frederick II of Denmark, who resigned the lands to his brother Duke Magnus of Holstein until the island was taken back to the direct administration of Denmark and in 1645 became a part of Sweden by the Treaty of Brömsebro.

References

- ^ A History of Pagan Europe By Prudence Jones, Nigel Pennick; p.195 ISBN 0-415-09136-5

- ^ Template:No iconOlav Trygvassons saga at School of Avaldsnes

- ^ Heimskringla; Kessinger Publishing (March 31, 2004); on Page 116; ISBN 0-7661-8693-8

- ^ A History of Pagan Europe by Prudence Jones; on page 166; ISBN 0-415-09136-5

- ^ Nordic Religions in the Viking Age by Thomas A. Dubois; on page 177; ISBN 0-8122-1714-4

- ^ The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia ISBN 0-231-12889-4

- ^ History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen By Adam of Bremen Page 196-197

- ^ The Baltic Crusade By William L. Urban; p. 20 ISBN 0-929700-10-4

- ^ Pre- and Proto-historic Finns by John Abercromby p.141

- ^ Heimskringla; 36. OF YNGVAR'S FALL

- ^ Through Past Millennia: Archaeological Discoveries in Estonia

- ^ The raid on Sigtuna

- ^ The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia, Page 193 ISBN 0-231-12889-4

- ^ Estonian Collections : Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norman and later British Coins; ISBN 0-19-726220-1

- ^ The Northern Crusades: Second Edition by Eric Christiansen; p.93; ISBN 0-14-026653-4

- ^ The Baltic Crusade By William L. Urban; p 113-114 ISBN 0-929700-10-4

- ^ Liv-, est- und kurländisches Urkundenbuch: Nebst Regesten