The Diary of a Young Girl: Difference between revisions

m Fixed a misspelling. |

Scottaleger (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

* [http://www.annefrank.org/content.asp?pid=122&lid=2 Article on Anne Frank the writer] |

* [http://www.annefrank.org/content.asp?pid=122&lid=2 Article on Anne Frank the writer] |

||

* [http://www.ushmm.org/museum/exhibit/focus/antisemitism/voices/transcript/?content=20090409 ''Voices on Antisemitism'' Interview with Sayana Ser] from the [http://www.ushmm.org/ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum] |

* [http://www.ushmm.org/museum/exhibit/focus/antisemitism/voices/transcript/?content=20090409 ''Voices on Antisemitism'' Interview with Sayana Ser] from the [http://www.ushmm.org/ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum] |

||

* [http://www.printsasia.com/book/anne-frank-the-diary-of-a-young-girl-anne-frank-0553296981 Anne Frank The Diary of a Young Girl]; [[Special:BookSources/0-55-329698-1|ISBN : 0-55-329698-1]] (paperback); published by [[Bantam_Books|Bantam Books]] |

|||

{{Anne Frank in other forms}} |

{{Anne Frank in other forms}} |

||

Revision as of 07:58, 19 September 2012

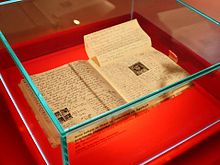

1947 first edition cover | |

| Author | Anne Frank |

|---|---|

| Original title | Het Achterhuis |

| Translator | B. M. Mooyaart |

| Cover artist | Helmut Salden |

| Language | Dutch |

| Subject | WWII, Nazi occupation of the Netherlands |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Contact Publishing |

Publication date | 1947 |

| Publication place | Netherlands |

Published in English | 1952 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| OCLC | 1432483 |

The Diary of a Young Girl is a book of the writings from the Dutch language diary kept by Anne Frank while she was in hiding for two years with her family during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. The family was apprehended in 1944 and Anne Frank ultimately died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. The diary was retrieved by Miep Gies, who gave it to Anne's father, Otto Frank, the only known survivor of the family. The diary has now been published in more than 60 different languages.

First published under the title Het Achterhuis. Dagboekbrieven 14 juni 1942 – 1 augustus 1944 (The Annex: Diary Notes from 14 June 1942 – 1 August 1944) by Contact Publishing in Amsterdam in 1947, it received widespread critical and popular attention on the appearance of its English language translation Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl by Doubleday & Company (United States) and Valentine Mitchell (United Kingdom) in 1952. Its popularity inspired the 1955 play The Diary of Anne Frank by the screenwriters Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, which they subsequently adapted for the screen for the 1959 movie version. The book is in several lists of the top books of the 20th century.[1]

Summary

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2012) |

During the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands Anne Frank began to keep a diary on June 14, 1942, two days after her 13th birthday, and twenty two days before going into hiding with her mother Edith Frank, father Otto Frank, sister Margot Frank and three other people, Hermann van Pels, Auguste van Pels, and Peter van Pels. The group went into hiding in the sealed-off upper rooms of the annex of her father's office building in Amsterdam. The sealed-off upper-rooms also contained a hidden door behind which the Franks would hide during the parts when Nazi soldiers were investigating the buildings for harbored Jews. Mrs. van Pels' dentist, Fritz Pfeffer, joined them four months later. In the published version, names were changed: the van Pels are known as the Van Daans and Fritz Pfeffer is known as Mr. Dussel. With the assistance of a group of Otto Frank's trusted colleagues, they remained hidden for two years and one month, until their betrayal in August 1944, which resulted in their deportation to Nazi concentration camps. Of the group of eight, only Otto Frank survived the war. Anne died in Bergen-Belsen from a typhus infection in early March, shortly (about two weeks) before liberation by British troops in April 1945.

Anne Frank's compositions

In manuscript, Anne's original diaries are written over three extant volumes. The first covers the period between 14 June 1942 and 6 December 1942. Since the second volume begins on 22 December 1943 and ends on 17 April 1944, it is assumed that the original volume or volumes between December 1942 and December 1943 were lost - presumably after the arrest, when the hiding place was emptied on Nazi instructions. However, this missing period is covered in the version Anne rewrote for preservation. The third existing notebook contains entries from 17 April 1944 to 1 August 1944, when Anne wrote for the last time before her arrest.

The diary is not written in the classic forms of "Dear Diary" or as letters to one's self, but as letters to imaginary friends "Kitty", "Conny", "Emmy", "Pop", and "Marianne". Anne used the various names until November 1942, when the first notebook ends. By the time she started the second existing volume, there was only one imaginary friend she was writing to: "Kitty". In her later re-writes, Anne changed the address of all the diary entries to "Kitty".

There has been much conjecture about the identity or inspiration of Kitty, who in Anne's revised manuscript is the sole recipient of her letters. In 1996, the critic Sietse van der Hoek wrote that the name referred to Kitty Egyedi, a prewar friend of Frank. Van der Hoek may have been informed by the 1970 publication A Tribute to Anne Frank, prepared by the Anne Frank Foundation, which assumed a factual basis for the character in its preface by the then chairman of the Foundation, Henri van Praag, and accentuated this with the inclusion of a group photograph that singles out Anne, Sanne Ledermann, Hanneli Goslar, and Kitty Egyedi. Anne does not mention Kitty Egyedi in any of her writings (in fact, the only other girl mentioned in her diary from the often reproduced photo, other than Goslar and Ledermann, is Mary Bos, whose drawings Anne dreamed about in 1944) and the only comparable example of Anne's writing unposted letters to a real friend are two farewell letters to Jacqueline van Maarsen, from September 1942.

Theodor Holman wrote in reply to Sietse van der Hoek that the diary entry for 28 September 1942 proved conclusively the character's fictional origin. Jacqueline van Maarsen agreed, but Otto Frank assumed his daughter had her real acquaintance in mind when she wrote to someone of the same name. However, Kitty Egyedi said in an interview that she was flattered by the assumption but doubted the diary was addressed to her:

Kitty became so idealized and started to lead her own life in the diary that it ceases to matter who is meant by 'Kitty'. The name ... is not meant to be me.

— Kitty Egyedi

Anne had expressed the desire in the re-written introduction of her diary for one person that she could call her truest friend, that is, a person to whom she could confide her deepest thoughts and feelings. She observed that she had many "friends" and equally many admirers, but (by her own definition) no true, dear friend with whom she could share her innermost thoughts. She originally thought her girlfriend Jacque van Maarsen would be this person, but that was only partially successful. In an early diary passage, she remarks that she is not in love with Helmut "Hello" Silberberg, her suitor at that time, but considered that he might become a true friend. In hiding, she invested much time and effort into her budding romance with Peter van Pels, thinking he might evolve into that one, true friend, but that was eventually a disappointment to her in some ways, also, though she still cared for him very much. Ultimately, the closest friend Anne had during her tragically short life was her diary, "Kitty", for it was only to "Kitty" that she entrusted her innermost thoughts.

Frank's already budding literary ambitions were galvanized on 29 March 1944 when she heard a broadcast made by the exiled Dutch Minister for Education, Art and Science, Gerrit Bolkestein, calling for the preservation of "ordinary documents—a diary, letters ... simple everyday material" to create an archive for posterity as testimony to the suffering of civilians during the Nazi occupation, and on 20 May notes that she has started re-drafting her diary with future readers in mind. She expanded entries and standardized them by addressing all of them to Kitty, clarified situations, prepared a list of pseudonyms, and cut scenes she thought would be of little interest or too intimate for general consumption. This manuscript, written on loose sheets of paper, was retrieved from the hiding place after the arrest and given to Otto Frank, with the original notes, when his daughter's death was confirmed in the autumn of 1945. Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl had rescued them along with other personal possessions after the family's arrest and before their rooms were ransacked by the Dutch police and the Gestapo.

When Otto Frank eventually began to read his daughter's diary, he was astonished. He said to Miep Gies, "I never knew my little Anne was so deep".[citation needed] He also remarked that the clarity with which Anne had described many everyday situations brought those since-forgotten moments back to him vividly.[citation needed]

Editorial history

Anne Frank's diary is among the most enduring documents of the 20th century. Initially, she wrote it strictly for herself. Then, one day in 1944, Gerrit Bolkestein, a member of the Dutch government in exile, announced in a radio broadcast from London that after the war he hoped to collect eyewitness accounts of the suffering of the Dutch people under the German occupation, which could be made available to the public. As an example, he specifically mentioned letters and diaries. Anne Frank decided that when the war was over she would publish a book based on her diary. Because she did not survive the war, it fell instead to her father to see her diary published.

The first transcription of Anne's diary was made by Otto Frank for his relatives in Switzerland. The second, a composition of Anne Frank's rewritten draft, excerpts from her essays, and scenes from her original diaries, became the first draft submitted for publication, with an epilogue written by a family friend explaining the fate of its author. In the spring of 1946 it came to the attention of Dr. Jan Romein, a Dutch historian, who was so moved by it that he immediately wrote an article for the newspaper Het Parool:

This apparently inconsequential diary by a child, this "de profundis" stammered out in a child's voice, embodies all the hideousness of fascism, more so than all the evidence of Nuremberg put together.

— Jan Romein

This caught the interest of Contact Publishing in Amsterdam, who approached Otto Frank to submit a draft of the manuscript for their consideration. They offered to publish but advised Otto Frank that Anne's candor about her emerging sexuality might offend certain conservative quarters and suggested cuts. Further entries were deleted before the book was published on 25 June 1947. It sold well; the 3000 copies of the first edition were soon sold out, and in 1950 a sixth edition was published.

At the end of 1950, a translator was found to produce an English-language version. Barbara Mooyaart-Doubleday was contracted by Vallentine, Mitchell & Co. in England and by the end of the following year her translation was submitted, now including the deleted passages at Otto Frank's request and the book appeared in America and Great Britain 1952, becoming a bestseller. Translations into German, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Japanese, and Greek followed. The play based on the diary won the Pulitzer Prize for 1955, and the subsequent movie earned Shelley Winters an Academy Award for her performance, whereupon Winters donated her Oscar to the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam.[2]

Other English translations

In 1989 The Diary of Anne Frank: The Revised Critical Edition presented the Barbara Mooyaart-Doubleday translation alongside Anne Frank's two other draft versions, and incorporated the findings of the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation into allegations of the Diary's authenticity.[3]

A new translation by Susan Massotty based on the unexpurgated text was published in 1995. It was also translated into Chinese.[4]

Criticism

Anne Frank's story has become symbolic of the scale of Nazi atrocities during the war, a stark example of Jewish persecution under Adolf Hitler, and a dire warning of the consequences of persecution. However, there have been many claims that Anne Frank's diary was fabricated.[5] Holocaust deniers such as Robert Faurisson have claimed that the diary is a forgery,[6] though critical and forensic studies of the text and the original manuscript have supported its authenticity.[7]

Otto Frank had stated that prior to the book's original publication in 1947 he cut many passages from the transcript that his publishers advised would be of little interest to the general reader. He was also advised to assign pseudonyms to protect the identities of those Anne Frank had mentioned by name. Some, such as David Irving, have suggested this was evidence that the published version was not an accurate transcription of the manuscripts, and even that the work had been written wholly or partly by Otto Frank or one of his associates.

In his will, Otto Frank bequeathed his daughter's original manuscripts to the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation. After his death in 1980, the Institute commissioned a forensic study of the manuscripts. The material composition of the original notebooks as well as the ink and handwriting found within them and the loose version were extensively examined. In 1986, the results were published; the handwriting was positively matched with contemporary samples of Anne Frank's handwriting and the paper, ink and glue found in the diaries and loose papers were consistent with materials available in Amsterdam during the period in which the diary was written.[7]

The survey of her manuscripts compared an unabridged transcription of Anne Frank's original notebooks with the entries she expanded and clarified on loose paper in a rewritten form and the final edit as it was prepared for the English translation. The investigation revealed that all of the entries in the published version were accurate transcriptions of manuscript entries in Anne Frank's handwriting, and that they represented approximately a third of the material collected for the initial publication. The magnitude of edits to the text is comparable to other historical diaries such as those of Katherine Mansfield, Anaïs Nin and Leo Tolstoy in that the authors revised their diaries after the initial draft, and the material was posthumously edited into a publishable manuscript by their respective executors, only to be superseded in later decades by unexpurgated editions prepared by scholars.[8]

Banning

In 2010, the Culpeper County, Virginia school system banned the 50th Anniversary "Definitive Edition" of Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, due to "complaints about its sexual content and homosexual themes."[9] This version "includes passages previously excluded from the widely read original edition...Some of the extra passages detail her emerging sexual desires; others include unflattering descriptions of her mother and other people living together."[10] After consideration, it was decided a copy of the newer version would remain in the library and classes would revert to using the older version.

The American Library Association stated that there have been six challenges to the book in the United States since it started keeping records on bans and challenges in 1990, and "Most of the concerns were about sexually explicit material".[10]

See also

References

- ^ Goodreads Best (100) Books of the 20th Century #8; The Guardian's (top 10) definitive book(s) of the 20th century out of 50 Best Books defining the 20th century; National Review's List of the 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of the Century #20; The New York Public Library's Books of the Century: War, Holocaust, Totalitarianism. 1996 ISBN 978-0-19-511790-5; Waterstone's Top100 Books of the 20th century, while there are several editions of the book. The publishers made a children's edition and an adult which is thicker. There are hardcovers and paperbacks. #26

- ^ Anne Frank House

- ^ Frank, Anne and Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation (2003) [1989]. The Diary of Anne Frank: The Revised Critical Edition. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-50847-6.

- ^ See Frank 1947

- ^ "The nature of Holocaust denial: What is Holocaust denial?", JPR report, 3, 2000

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Faurisson, Robert (1982), "Is The Diary of Anne Frank genuine?", The Journal of Historical Review, 3 (2): 147

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Mitgang, Herbert (June 8, 1989), An Authenticated Edition of Anne Frank's Diary, New York Times

- ^ Lee, Hermione (December 2, 2006), The Journal of Katherine Mansfield, The Guardian

- ^ "The Neverending Campaign to Ban 'Slaughterhouse Five'". The Atlantic. August 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Michael Alison Chandler (January 29, 2010). "School system in Va. won't teach version of Anne Frank book". Washington Post.

Further reading

Editions of the diary

- Frank, Anne (1995) [1947], Frank, Otto H.; Pressler, Mirjam (eds.), Het Achterhuis (in Dutch), Massotty, Susan (translation), Doubleday, ISBN 0-553-29698-1

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|lastauthoramp=,|laydate=,|month=,|laysummary=, and|separator=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) ; This edition, a new translation, includes material excluded from the earlier edition. - Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank, Eleanor Roosevelt (Introduction) and B.M. Mooyaart (translation). Bantam, 1993. ISBN 0-553-29698-1 (paperback). (Original 1952 translation)

- The Diary of Anne Frank: The Critical Edition, Harry Paape, Gerrold Van der Stroom, and David Barnouw (Introduction); Arnold J. Pomerans, B. M. Mooyaart-Doubleday (translators); David Barnouw and Gerrold Van der Stroom (Editors). Prepared by the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation. Doubleday, 1989.

- The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definitive Edition, Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler (Editors); Susan Massotty (Translator). Doubleday, 1991.

- Frank, Anne and Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation (2003) [1989]. The Diary of Anne Frank: The Revised Critical Edition. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-50847-6.

Adaptations

- "A Graphic Biography:The Anne Frank Diary, by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón, is to be published in April 2010[needs update] by Uitgeverij Luitingh in The Netherlands.

Other writing by Anne Frank

- Frank, Anne. Tales from the Secret Annex: Stories, Essay, Fables and Reminiscences Written in Hiding, Anne Frank (1956 and revised 2003)

Publication history

- Lisa Kuitert: De uitgave van Het Achterhuis van Anne Frank, in: De Boekenwereld, Vol. 25 hdy dok

Biography

- Anne Frank Remembered: The Story of the Woman Who Helped to Hide the Frank Family, Miep Gies and Alison Leslie Gold, 1988. ISBN 0-671-66234-1 (paperback).

- The Last Seven Months of Anne Frank, Willy Lindwer. Anchor, 1992. ISBN 0-385-42360-8 (paperback).

- Anne Frank: Beyond the Diary – A Photographic Remembrance, Rian Verhoeven, Ruud Van der Rol, Anna Quindlen (Introduction), Tony Langham (Translator) and Plym Peters (Translator). Puffin, 1995. ISBN 0-14-036926-0 (paperback).

- Memories of Anne Frank: Reflections of a Childhood Friend, Hannah Goslar and Alison Gold. Scholastic Paperbacks, 1999. ISBN 0-590-90723-9 (paperback).

- An Obsession with Anne Frank: Meyer Levin and the Diary, Lawrence Graver, University of California Press, 1995.

- Roses from the Earth: The Biography of Anne Frank, Carol Ann Lee, Penguin 1999.

- The Hidden Life of Otto Frank,, 2002.

- Anne Frank: The Biography, Melissa Muller, Bloomsbury 1999.

- My Name Is Anne, She Said, Anne Frank, Jaqueline Van Maarsen, Arcadia Books 2007.

External links

- Anne Frank House website

- Anne Frank Trust UK website

- The Anne Frank Center USA website

- Anne Frank Remembered at IMDb, Jon Blair, 1995. (DVD)

- QuickTime video. Miep Gies describes giving Anne Frank's papers to Otto Frank

- QuickTime interview with Otto Frank's second wife, about the publication of Anne Frank's diary

- Anne's manuscripts

- Article about the publication of Het Achterhuis, by The Anne Frank House

- Online exhibition of Anne Frank's manuscripts

- Article on Anne Frank the writer

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Sayana Ser from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Anne Frank The Diary of a Young Girl; ISBN : 0-55-329698-1 (paperback); published by Bantam Books