College tuition in the United States: Difference between revisions

Reverting: There was consensus in talk that this edit would be OK if credible sources could be found: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Talk:College_tuition_in_the_United_States&diff=next&oldid=654353593 Reverting. |

Title states "recommendations to address rising tuition have been advanced by experts and consumer and students' rights advocates:" User:Flyte35 stated "not a recommendation" FACT These ARE recommendations by experts/advocates to address rising tuitio |

||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

** "The National Center for Education Statistics should increase the frequency of the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study to annual, from triennial, in order to permit more timely tracking of the factors affecting tuition rate increases. Likewise, NCES (National Center for Education Statistics) should take steps to improve the efficiency of the data collection and publication for the Digest of Education Statistics, so that all tables will include more recent data. The most recent data listed in some tables is five years old." |

** "The National Center for Education Statistics should increase the frequency of the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study to annual, from triennial, in order to permit more timely tracking of the factors affecting tuition rate increases. Likewise, NCES (National Center for Education Statistics) should take steps to improve the efficiency of the data collection and publication for the Digest of Education Statistics, so that all tables will include more recent data. The most recent data listed in some tables is five years old." |

||

** "The US Department of Education should study the relationship between increases in average EFC (Expected Family Contribution) figures and average tuition rates. In addition, it would be worthwhile to examine how historical average EFC figures have changed relative to family income when measured on a current and constant dollar basis for each income quartile." |

** "The US Department of Education should study the relationship between increases in average EFC (Expected Family Contribution) figures and average tuition rates. In addition, it would be worthwhile to examine how historical average EFC figures have changed relative to family income when measured on a current and constant dollar basis for each income quartile." |

||

* Other popular ways to address the rising tuition problems faced by students include completing your general education requirements at a community college, which is much cheaper than initially going to a university, obtaining scholarships and other financial aid, as well as looking for ways to pay in-state tuition.<ref name=Cutting>{{cite web | last=Kantrowitz | first=Mark | title=Cutting College Costs|publisher=FinAid|year=2013|url=http://www.finaid.org/questions/cuttingcollegecosts.phtml|accessdate= 24 July 2013}}</ref> |

|||

* Lastly, in order to cope with the rising cost of tuition, many students have started working part-time.<ref name="Cutting"/><ref>{{cite web | title=How to Cope with Rising Tuition Costs|publisher=Global Campus For Students|year=2011|url=http://www.gcstudent.org/how-to-cope-with-rising-tuition-costs|accessdate= 22 July 2013}}</ref> When it comes to getting a job after college, to further cope with the rising costs of tuition, some experts have suggested that the best move might be to get a job while in college.<ref>{{cite web|last=Watson|first=Bruce|title=How to Go to College Without Going Broke (and Yes, You Still Should)|url=http://www.dailyfinance.com/2011/11/03/how-to-go-to-college-without-going-broke-and-yes-you-still-sho|publisher=Daily Finance|date=3 November 2011| accessdate=22 July 2013}}</ref> To facilitate these recommendations, some colleges help students in job searches and job placement after graduation.<ref>{{cite web|title=Top 10 Job Placement Colleges: INFORMATION AND TIPS ON INTERNSHIPS AND PAID INTERNSHIP|publisher=CollegeTips.com| year=2011|url=http://www.collegetips.com/college-money/college-job-placement.php|accessdate= 22 July 2013}}</ref> |

|||

==Historical trends== |

==Historical trends== |

||

Revision as of 08:53, 24 May 2015

College tuition refers to tuition (instruction) fees that students have to pay to colleges in the United States. Tuition increases in the U.S. have caused chronic controversy since shortly after World War II. It was during a time when the workforce was slow from the aftermath of war and higher education was blooming in order to pursue more knowledge in hopes of finding a successful, stable career.[1] Many families went into debt in order to pay for their children to attend college.[2] Except for its military academies, the U.S. federal government does not directly support higher education. Instead it offers loans and grants, dating back to the Morrill Act during the U.S. Civil War and the "G.I. Bill" programs implemented after World War II.

Overview of tuition rates in the U.S.

The United States has one of the most expensive higher education systems in the world.[3][4] Public colleges have no control over one major revenue source — the state.[5] In 2012-13, the average cost of annual tuition in the United States ranged from $3,131 for public two-year institutions (community colleges) to $29,056 for private four-year institutions.[6] Private colleges increased their tuition by an average of 3.9 percent in 2012-13, the smallest rise in four decades, according to the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities.[7] The most expensive university, in terms of tuition and fees alone, is currently Columbia University in New York, at $51,008 in tuition and fees, according to the US News and World Report.[8]

Causes of tuition increases

Cost shifting and privatization

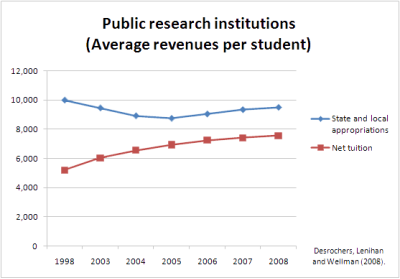

One cause of increased tuition is the reduction of state and federal appropriations to state colleges, causing the institutions to shift the cost over to students in the form of higher tuition. State support for public colleges and universities has fallen by about 26 percent per full-time student since the early 1990s.[10] In 2011, for the first time, American public universities took in more revenue from tuition than state funding.[9][11] Critics say the shift from state support to tuition represents an effective privatization of public higher education.[11][12] About 80 percent of American college students attend public institutions.[10]

Bubble theory

The view that higher education is a bubble is controversial. Most economists do not think the returns to college education are falling.[13]

One rebuttal to the claims that a bubble analogy is misleading is the observation that the 'bursting' of the bubble are the negative effects on students who incur student debt, for example, as the American Association of State Colleges and Universities reports that "Students are deeper in debt today than ever before...The trend of heavy debt burdens threatens to limit access to higher education, particularly for low-income and first-generation students, who tend to carry the heaviest debt burden. Federal student aid policy has steadily put resources into student loan programs rather than need-based grants, a trend that straps future generations with high debt burdens. Even students who receive federal grant aid are finding it more difficult to pay for college."[14]

Student loan

Another proposed cause of increased tuition is U.S. Congress' occasional raising of the 'loan limits' of student loans, in which the increased availability of students to take out deeper loans sends a message to colleges and universities that students can 'afford more,' and then, in response, institutions of higher education raise tuition to match, leaving the student back where he began, but deeper in debt. Therefore, if the students are able to afford a much higher amount than the free market would otherwise support for students without the ability to take out a loan, then the tuition is 'bid up' to the new, higher, level that the student can now afford with loan subsidies.[15] One rebuttal to that theory is the fact that even in years when loan limits have not risen, tuition has still continued to climb.[16][17] Keeping tuition increases at the rate of inflation would require the state kick in $128 million more tax dollars between now and 2015.[18] Public college tuition has jumped 33 percent nationwide since 2000.[19] College students are facing a roughly $20 billion increase in the cost of their federal loans.[20]

Lack of consumer protection

A third, novel, theory claims that the recent change in federal law removing all standard consumer protections (truth in lending, bankruptcy proceedings, statutes of limits, the right to refinance, adherence to usury laws, and Fair Debt & Collection practices, etc.) strips students of the ability to declare bankruptcy, and, in response, the lenders and colleges know that students, defenseless to declare bankruptcy, are on the hook for any amount that they borrow -including late fees and interest (which can be capitalized and increase the principal loan amount), thus removing the incentive to provide the student with a reasonable loan that he/she can pay back.[16][17] As proof of this theory, it has been shown that returning bankruptcy protections (and other Standard Consumer Protections) to Student Loans would cause lenders to be more cautious, thereby causing a sharp decline in the availability of student loans, which, in turn, would decrease the influx of dollars to colleges and universities, who, in turn, would have to sharply decrease tuition to match the lower availability of funds.[21] Under this theory, if student loans did not have the ability to file for bankruptcy, it would be more profitable for the lender if the student defaulted (due to the increases in the amount of the loan after fees and interest are capitalized), and thus there is no free market pressure-type motive for the lender or the college to help the student avoid default. This is especially true because the government, if it is the lender or guarantor of the loan, has the ability to garnish the borrower's wages, tax return, and Social Security Disability income without a court order.[22] Some have called the Federal Government 'predatory' for making loans which will have such a high default rate, since the default rate for Student Loans is projected to reach 46.3% of all federal dollars disbursed to students at for-profit colleges in 2008 (Budget lifetime default rate, loan default rate only 18.6%, meaning that 18.6% of all loans contain 46.3% of all dollars loaned out).[23][24]

Additional factors

Other factors[12] that have been implicated in increased tuition include the following:

- Colleges and universities have accumulated multi-billion dollar endowments, especially at elite universities. Harvard University announced its endowment was worth $32 billion, and Yale reported an endowment of $19.4 billion on returns that were tax-exempt.[25] In 2011, California's two public university systems had more than $7 billion in endowment funds but raised tuition fees by 21% combined.[26] These figures raise related concerns about "institutional gap" — meaning that universities may not be managing their endowments appropriately and that other universities try to compete with elite institutions, thus charging higher tuition fees in the competition to retain high faculty- and status-ranking.[27]

- The practice of 'tuition discounting,' in which a college awards financial aid from its own funds. This assistance to low-income students means that 'paying' students have to 'make up' for the difference: increased tuition.[12] According to Inside Higher Ed, a 2011 report from the National Association of College and University Business Officers explains more about the practice of tuition discounting. The article notes that "while the total amount spent on institutional aid for freshmen rose, the average amount that institutions spent per student actually dropped slightly," and gives, as one possible reason for this drop, that between 2008 and 2011 "colleges and universities had to lower the amount they gave to each student to help cover a larger number of students."[28]

- According to Mark Kantrowitz, a recognised expert in this area, "The most significant contributor to tuition increases at public and private colleges is the cost of instruction. It accounts for a quarter of the tuition increase at public colleges and a third of the increase at private colleges."[19]

- Kantrowitz' study also found that "Complying with the increasing number of regulations — in particular, with the reporting requirements — adds to college costs," thus contributing to a rise in tuition to pay for these additional costs. Since deregulation, the average cost of tuition and fees at the state’s public universities has increased by 90 percent, according to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. Of the 181 members of the state’s 83rd Legislature, more than 50 have voted at least once to advance efforts to end tuition deregulation, while fewer than 20 have consistently voted to uphold it. Many have never voted on the issue, and more than 40 members are freshmen. This rise, however, is not entirely negative. Tuition increases help universities make up for that in their budgets.[19]

Recommendations

Based on the available data, recommendations to address rising tuition have been advanced by experts and consumer and students' rights advocates:

- Because schools are assured of receiving their fees no matter what happens to their students, they have felt free to raise their fees to very high levels, to accept students of inadequate academic ability, and to produce too many graduates in some fields of study. Therefore, schools should be penalized when their students default on their student loans.[29][30]

- Tax the endowment income of universities and link the endowment tax to tuition rates.[31]

- Colleges and universities should look for ways to reduce costs of instructor and administrator expenditures (e.g., cut salaries and/or reduce staff).[32][33]

- State and federal governments should increase appropriations, grants, and contracts to colleges and universities.[32][34][35]

- Federal, state, and local governments should reduce the regulatory burden on colleges and universities.[12]

- The federal government should enact partial or total loan forgiveness for students who have taken out student loans.[33][36][37][38] One advocate for college loan forgiveness[39] has argued that "Since forgiveness does not require the printing of new dollars (i.e., "too much money chasing too few goods"),[40] it is not inflationary." Other advocates[41] have argued the same thing from the opposite angle, namely that the "lack of consumer protections," particularly "removing bankruptcy protections,"[42] for college loans, has led to inflation.

- Federal lawmakers should return standard consumer protections (truth in lending, bankruptcy proceedings, statutes of limitations, etc.) to student loans which were removed by the passage of the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-394, enacted October 22, 1994), which amended the FFELP (Federal Family Education Loan Program).[33][43][44]

- Cut lender subsidies, decrease student reliance on loans to pay for college, and otherwise reduce the 'loan limits' to limit the amount a student may borrow.[33][45][46]

- Regulatory or legislative action to lower or freeze the tuition, such as Canada's tuition freeze model, should be enacted by federal lawmakers:[47] Potential downsides to tuition-freezing guarantees are evident, being offered by only few dozen colleges. Under the guarantees, the student's tuition does not change for the extent of their education. Each year's freshmen pay a higher rate, which is then guaranteed through their years in college.[5] About 1 in 3 college students transfers to another school at some point. If tuition freezes become the default model for colleges, students would feel less able to change schools because they would be entering at a new, probably higher tuition.[5]

- Kantrowitz, issued the following recommendations:[12]

- "The National Center for Education Statistics should increase the frequency of the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study to annual, from triennial, in order to permit more timely tracking of the factors affecting tuition rate increases. Likewise, NCES (National Center for Education Statistics) should take steps to improve the efficiency of the data collection and publication for the Digest of Education Statistics, so that all tables will include more recent data. The most recent data listed in some tables is five years old."

- "The US Department of Education should study the relationship between increases in average EFC (Expected Family Contribution) figures and average tuition rates. In addition, it would be worthwhile to examine how historical average EFC figures have changed relative to family income when measured on a current and constant dollar basis for each income quartile."

- Other popular ways to address the rising tuition problems faced by students include completing your general education requirements at a community college, which is much cheaper than initially going to a university, obtaining scholarships and other financial aid, as well as looking for ways to pay in-state tuition.[48]

- Lastly, in order to cope with the rising cost of tuition, many students have started working part-time.[48][49] When it comes to getting a job after college, to further cope with the rising costs of tuition, some experts have suggested that the best move might be to get a job while in college.[50] To facilitate these recommendations, some colleges help students in job searches and job placement after graduation.[51]

Historical trends

The first chart compares standard undergraduate annual tuition and fees charged by major U.S. public, U.S. private and Canadian public 4-year college, showing both current U.S. dollars during the years from 1940 to 2000 and U.S. dollars adjusted to the year 2000 by using the U.S. Consumer Price Index series.[52][53][54]

Tuition at the University of Toronto tracked close to inflation rates during the entire period.[55] The University of Iowa had rapid increases in tuition during the 1950s and then tracked close to inflation rates since that time.[56] The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), among the most expensive of the private U.S. educational institutions throughout the 20th century,[57] had continual large tuition increases, dipping slightly below inflation rates only during the World War II years.[58][59]

Over the 60-year period charted, the inflation-adjusted, long term, annual increases in tuition at these institutions were 0.4 percent for the University of Toronto, 1.4 percent for the University of Iowa, and 2.1 percent for MIT.[60] Other institutions in the same categories differ in details but not in general patterns.[61] The results of the trends are that over the 60 years shown, adjusted for inflation, the tuition at the University of Iowa increased by a factor of 2.3 and that at MIT by a factor of 3.6, while tuition at the University of Toronto rose only about 30 percent.[62]

Recent trends

This chart compares average undergraduate tuition and fees charged by about 600 U.S. public and 1,350 U.S. private, non-profit 4-year colleges during years from 1993 through 2004.,[63] both unadjusted and adjusted to the year 2004 by using the U.S. Consumer Price Index series. Data were not available for years 1994, 1995 and 1999.

During the 11-year period charted, both public and private, nonprofit colleges regularly posted tuition increases well above inflation rates. Peak increases for private colleges were in 1997, after the U.S. economy began booming growth. Peak increases for public colleges were in 2003, after state budgets supporting most of them were crimped by a sharp economic recession. Over this period, annual, inflation-adjusted tuition increases at public colleges averaged 4.0 percent, while those at private, non-profit colleges averaged 3.5 percent. Cumulative results over this period are average public tuitions growing 53 percent above inflation, and average private, nonprofit tuitions growing 47 percent above inflation. As of 2004, private, nonprofit colleges cost on average 3.3 times as much as public colleges attended by residents of their states.

Recent data from 2010 to 2011 have shown that tuition and fees rose by 4.5% at private colleges and more than 8% at public institutions. Not only do these numbers mean that the sticker price of higher education is far outpacing inflation rate and affordability, but it also means that tuition has grown almost 500% since 1986.[25]

Disproportional inflation of college costs

"Disproportional inflation" refers to inflation in a particular economic sector that is substantially greater than inflation in general costs of living.

The following graph shows the inflation rates of general costs of living (for urban consumers; the CPI-U), medical costs (medical costs component of the consumer price index (CPI)), and college and tuition and fees for private four-year colleges (from College Board data) from 1978 to 2008. All rates are computed relative to 1978. [64]

Cost of living increased roughly 3.25-fold during this time; medical costs inflated roughly 6-fold; but college tuition and fees inflation approached 10-fold. Another way to say this is that whereas medical costs inflated at twice the rate of cost-of-living, college tuition and fees inflated at four times the rate of cost-of-living inflation. Thus, even after controlling for the effects of general inflation, 2008 college tuition and fees posed three times the burden as in 1978.

According to the College Board, the average tuition price for a 4-year public college in 2008-2009 was $6,585 compared to 2004 when the price was slightly above $5,000. The average price of in-state tuition vs out-of-state tuition for 2008-2009 was $6,585 for a in-state 4-year college to $17,452 for out-of-state 4 year college (collegeboard.com). The mean increase in college tuition is 4.2% annually[65]

Economic and social concerns

Economic concerns

Long-term price trends make higher education an especially inflationary sector of the U.S. economy, with tuition increases in recent years sometimes outpacing even explosive health care sectors.[66] These trends are sources of continuing controversy in the United States over costs of higher education[67] and their potential for limiting the country's achievements in democracy, fairness and social justice.[68]

Social concerns

Besides economic effects of rapidly increasing debt burdens placed on students, there are social ramifications to higher student debt. Several studies demonstrate that students from lower income families are more likely to drop out of college to avoid debt.[69][70] [71] Studies indicate that more than 75% of college students report stress, including stress involving tuition challenges [72] Recent reports also indicate an increase in suicides directly attributable to the stress related to distressed and defaulted student loans.[73][74][75][76] The adverse mental health impacts on the student population due to economic-induced stress are becoming a social concern. Students generally have higher stress levels on their financial burden such as student loans, and foreseeable employment in the job market.[77]

Student loan debt

A closely related issue is the increase in student borrowing to finance college education and the resulting student loan debt. In the 1980s, federal student loans became the centerpiece of student aid received.[78] From 2006 -2012, federal student loans more than doubled and outstanding student loan debt grew to $807 billion.[78] One of the consequences of increased student borrowing is an increase in the number of defaults.[79] During this same time period, two-year default rates increased from 5.2 percent in 2006 to 9.1 percent in 2012 and more than doubled the historic low of 4.5 percent set in 2003.[80]

Since data collection began in 1987, the highest two-year default rate recorded was 22.4 percent in 1990.[80] In 2012, the U.S. Department of Education released detailed federal student loan default rates including, for the first time, three-year default rates. For-profit institutions had the highest average three-year default rates at 22.7 percent while public institutions rates were 11 percent and private non-profit institutions at 7.5 percent. More than 3.6 million borrowers from over 5,900 schools entered repayment during 2008-2009, and approximately 489,000 of them defaulted. For-profit colleges account for 10 percent of enrolled students but 44 percent of student loan defaults.[81]

In the 2007-2008 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), the median cumulative debt among graduating 4-year undergraduate students was $19,999; one quarter borrowed $30,526 or more, and one tenth borrowed $44,668 or more.[82] In 2010, the average debt of graduates of 4 year nonprofit universities across the country was $25,250, which is an overall rise of five percent from 2009.[83] In 2010 student loan debt surpassed 'Credit Card' debt.[22] Student debt in the United States has reached $1 trillion, almost a 50% increase from 2008.[84] As a result of the student loan and tuition crisis, studies have shown that students are experiencing stress under the current economic downturn and fiscal challenges.[85]

In his 2012 State of the Union Address, President Barack Obama, addressed the rising cost of higher education in the United States. Through an executive order in 2011, President Obama laid out a student loan plan, “Pay as you Earn,” that allows former students to pay education debts as a percentage of their incomes.[86] Furthermore, the Obama administration has developed a standardized letter to be sent to admitted students indicating the cost of attendance at an institution, including all net costs as well as financial aid received. Use of the letter is not mandatory.[87]

See also

- College admissions in the United States

- Credential inflation

- EdFund

- Free education

- Higher education bubble

- Higher Education Price Index

- Post-secondary education

- Private university

- Student benefit

- Student debt

- Student loans in the United States

- Tuition agency

- Tuition center

- Tuition fees

- Tuition freeze

References and notes

- ^ Campbell, Robert; Barry N. Siegel. "The Demand for Higher Education in the United States". Jstor. American Economic Association. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Lazerson, Marvin. "The Disappointments of Success: Higher Education after World War II". Jstor. Sage Publications, Inc. pp. 64–67. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ Hau, Wingfield (January 21, 2008). "The World's Most Expensive Universities". Forbes. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Vasagar, Jeevan (January 21, 2008). "UK tuition fees are third highest in developed world, says OECD". The Guardian. London. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Freezing tuition: It's not such a hot idea". Los Angeles Times. 2012.

- ^ "College Costs: FAQs". The College Board. 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ "Private College Tuition Up by 3.9%, Smallest Rise in 40 Years". Inside Higher Ed. October 5, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Snider, Susannah (September 9, 2014). "10 Most, Least Pricey Private Colleges and Universities". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ a b "Trends in College Spending 1998-2008" Delta Cost Project.

- ^ a b Luzer, Daniel (April 13, 2012). "Can We Make College Cheaper?". Washington Monthly. Retrieved 2012-04-17.

- ^ a b "Public Universities Relying More on Tuition Than State Money", The New York Times

- ^ a b c d e Kantrowitz, Mark (2002). "Research Report: Causes of faster-than-inflation increases in college tuition" (PDF). FinAid.

- ^ Claudia Goldin, Lawrence F. Katz (2008). The Race Between Education and Technology. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- ^ Hillman, Nick (2006). "Student Debt Burden, Volume 3, Number 8, August 2006" (PDF). American Association of State Colleges and Universities.

- ^ "Federal Student Loans: Patterns in Tuition, Enrollment, and Federal Stafford Loan Borrowing Up to the 2007-08 Loan Limit Increase". gao.gov. 2011.

- ^ a b "Student Loans in Bankruptcy". lawyers.com. 2011.

- ^ a b "Student Loan Bankruptcy Options". money-zine.com. 2011.

- ^ http://stateimpact.npr.org/indiana/2013/01/09/university-presidents-make-statehouse-appeal-for-higher-education-funding/

- ^ a b c Hamilton, Reeve (November 17, 2012). "Legislators Weigh Options for Tuition Deregulation". New York Times. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ "No more grace period on student-loan interest". Chicago Tribune. June 28, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Reilly, Peter J (2012). "Why College Prices Keep Rising". Forbes.com.

- ^ a b Dvorkin, Howard (2010). "Student Loan Debt Surpasses Credit Card Debt-What to Do?". foxbusiness.com.

- ^ Wienerbronner, Danielle (December 23, 2010). "46 Percent Of Federal Loans Paid To For-Profit Institutions Will Go Into Default". huffingtonpost.com/AOL.com.

- ^ Turner, Katrina (2010). "Subject: Default Rates for Cohort Years 2004–2008". ifap.ed.gov.

- ^ a b Willie, Matt (2012). "Taxing and Tuition: A Legislative Solution to Growing Endowments and the Rising Costs of a College Degree". Brigham Young University Law Review (5): 1665.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Willie, Matt (2012). "Taxing and Tuition: A Legislative Solution to Growing Endowments and the Rising Costs of a College Degree". Brigham Young University Law Review (5): 1669.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Willie, Matt (2012). "Taxing and Tuition: A Legislative Solution to Growing Endowments and the Rising Costs of a College Degree". Brigham Young University Law Review (5): 1670.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Kiley, Kevin (2011). "Discounting the Bottom Line". National Association of College and University Business Officers. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ "Harmful Effects of Federal Student Aid: Dollars, Cents, and Nonsense". Center for College Affordability and Productivity. 25 June 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ "Reflections on the underemployment of college graduates". Teachers College at Columbia University. 25 June 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Willie, Matt (2013). "Taxing and Tuition: A Legislative Solution to Growing Endowments and the Rising Costs of a College Degree" (PDF). Brigham Young University Law Review: 1667. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ a b Kantrowitz, Mark (2002). "Research Report: Causes of faster-than-inflation increases in college tuition" (PDF). FinAid.

- ^ a b c d Watts, GordonWayne (2011). "Higher-Ed Tuition Costs: The 'Conservative' view is not on either extreme". ThirstForJustice.net.

- ^ "Affordable Higher Education: Student Debt". U.S. PIRG. 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ "Fight to Protect Students and Taxpayers Moves to Senate! - House Voted to Slash Pell Grants and Block Gainful Employment Rule". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2011.

- ^ Applebaum, Robert (2009). "The Proposal". ForgiveStudentLoanDebt.com.

- ^ "Real Loan Forgiveness". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2011.

- ^ "Take Action for Real Loan Forgiveness!". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2009.

- ^ Watts, GordonWayne (2015). "Position Paper" (PDF). ThirstForJustice.net.

- ^ Investopedia, Investopedia (2010). "Inflation: What Is Inflation?". Investopedia.com.

- ^ Mockler, Garrett (2014). "Student Loan Justice Argument". TheWhiteWolfHasArrived.Tumblr.com.

- ^ Collinge, Alan (2012). "What Congress Can Do To Solve the Student Loan Crisis". NY Art World Commentary.

- ^ Collinge, Alan (2011). "Private Student Loan Bankruptcy Bill... The 4th Attempt". StudentLoanJustice.org.

- ^ "Bankruptcy Relief for Private Student Loan Borrowers Advances". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2010.

- ^ "Affordable Higher Education: Cutting Lender Subsidies". U.S. PIRG. 2011.

- ^ "Commission: Private Loans are Not the Solution!". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2006.

- ^ "Commission Calls for "Reduced Debt Burden" -- Time for Education Department to Act". ProjectOnStudentDebt.org. 2006.

- ^ a b Kantrowitz, Mark (2013). "Cutting College Costs". FinAid. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ^ "How to Cope with Rising Tuition Costs". Global Campus For Students. 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Watson, Bruce (3 November 2011). "How to Go to College Without Going Broke (and Yes, You Still Should)". Daily Finance. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ "Top 10 Job Placement Colleges: INFORMATION AND TIPS ON INTERNSHIPS AND PAID INTERNSHIP". CollegeTips.com. 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ "Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Dept. of Labor". Consumer Price Index.

- ^ Powell, James (2006). "Bank of Canada". A History of the Canadian Dollar.

- ^ To show a wide range of tuitions, the chart's vertical axis is logarithmic. The span between two horizontal lines is a factor of ten.

- ^ "Canadian Association of University Teachers". Education Review 4(1), Sept, 2002, p. 2, Table 1.

- ^ "University of Iowa". Fact Sheet, 2005.

- ^ For background on the emergence of MIT and other U.S. research universities, see Geiger, Roger L. (1986). To Advance Knowledge: The Growth of American Research Universities, 1900-1940. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "MIT Undergraduate Association". The Tech, 1994-2006.

- ^ "MIT Undergraduate Association". The Tech, Archives, 1881-2009.

- ^ Resident tuition rates are charted for public institutions; fees are averaged; nonresident rates are typically higher.

- ^ Note the qualitatively similar patterns in inflation-adjusted tuitions for three periods: 1940-1950, 1950-1980 and 1980-2000.

- ^ After 1960, these patterns show gradually widening ratios of private-school to public-school tuition, but some public systems saw tuition increases similar to those of the 1950s in Iowa during different decades.

- ^ "National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Dept. of Education". Average institutional charges for tuition and required fees.

- ^ Data sources listed in Uebersax, John (2009-07-15). "College Tuition: Inflation or Hyperinflation?". Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ Salam, Vance H. (2012). The College Cartel. National review Online.

- ^ Ehrenberg, Ronald G. (2002). Tuition Rising: Why College Costs So Much. Harvard University Press.

- ^ Kane, Thomas J. (1999). The Price of Admission: Rethinking How Americans Pay for College. Brookings Institution Press.

- ^ Bowen, William G., Tobin, Eugene M., Kurzweil, Martin A., and Pichler, Susanne C. (2005). Equity And Excellence In American Higher Education. University of Virginia Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hopper, Briallen and Johanna. "Should Working-Class People Get B.A.'s and Ph.D.'s?". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ Barrow, Lisa; Cecilia Elena Rouse (2005). "Does college still pay?". The Economists’ Voice. 2 (4): 1–4.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Luzer, Daniel (February 18, 2011). "Why Students Drop Out". Washington Monthly. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ^ May, Ross; Stephen Casazza (1 June 2012). "Academic Major as a Perceived Stress Indicator: Extending Stress Management Intervention". College Student Journal. 46 (2): 264.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Higher Ed NewsWeekly (p.57)" (PDF). Illinois Board of Higher Education. 2007.

- ^ "Student Loan Debt Drives Man to Suicide". Newsalert, citing The Chicago Sun-Times. 2007.

- ^ Lewis, Libby (2007). "A Pastor's Student Loan Debt". NPR.

- ^ Collinge, Alan (2007). "Company's march toward student loan monopoly scary". TheNewsTribune.com.

- ^ Guo, Yuh-Gen; Wang, Shu Ching; Johnson, Veronica (2011). "College Students' Stress Under Current Economic Downturn". College Student Journal. 45 (3): 540.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Taylor, A. N. (2012). Undo undue hardship: An objective approach to discharging federal student loans in bankruptcy.Journal of Legislation, 38(2), 185-236

- ^ Jones, J. (2010). Advocates urge quick action on rules governing for-profits: Institutions account for 10 percent of enrolled U.S. college students but 44 percent of student loan defaults. Diverse Issues in Higher Education, 27(12), 7.

- ^ a b "National Student Loan Two-year Default Rates: FY 2010 2-Year Official National Student Loan Default Rates". U.S. Department of Education, Office of Student Financial Assistance Programs. 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ United States Senate. (2010). Emerging Risk?: An Overview of Growth, Spending, Student Debt and Unanswered Questions in For-Profit Higher Education. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Information derived from Trends in Undergraduate Borrowing II: Federal Student Loans in 1995–96, 1999–2000, and 2003–04 (PDF) (Report). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. February 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Lewin, Tamar (2011). College Graduates’ Debt Burden Grew, Yet Again, in 2010. New York Times.

- ^ Harkin, Tom (18 October 2012). "Make College Costs More Transparent". TIME. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Guo, Yuh-Gen; Wang, Shu-Ching; Johnson, Veronica (2011). "College Students' Stress Under Current Economic Downturn". College Student Journal. 45 (3): 537.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Nakamura, David (October 26, 2011). "Obama moves to ease student loan burdens". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Government Gives Colleges a Model for Telling Students About Costs". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

External links

- "College, Inc.", PBS FRONTLINE documentary, May 4, 2010

- "College Costs Too Much Because Faculty Lack Power". The Chronicle of Higher Education. August 5, 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-08. by Robert E. Martin

- Going Broke by Degree: Why College Costs Too Much. American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. May 2004. ISBN 9780844741970. by Richard K. Vedder

- Why Does College Cost So Much?. Oxford University Press, USA. November 2010. ISBN 9780199744503. by Robert B. Archibald and David H. Feldman

- U.S. Dept. of Education