Karl May: Difference between revisions

→Mature work: Removing unsourced content Copyedit (major) |

→Other works: Removing unsourced content Copyedit (major) |

||

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

=== Other works === |

=== Other works === |

||

May was a member of the "Lyra" choir in about 1864 and composed musical works including a version of ''[[Ave Maria]]'' and ''Vergiss mich nicht'' within ''Ernste Klänge'', 1899).<ref name=KuehneLorenzMusik>Kühne H. and Lorenz C. F. ''Karl May und die Musik''. Verlag, Bamberg and Radebeul, 1999.</ref> |

|||

During his last years May |

During his last years, May lectured on his [[Philosophy|philosophic]] ideas. |

||

* ''Drei Menschheitsfragen: Wer sind wir? Woher kommen wir? Wohin gehen wir?'' ([[Lawrence, Massachusetts|Lawrence]], 1908) |

|||

* ''Sitara, das Land der Menschheitsseele'' ([[Augsburg]], 1909) |

|||

* ''Empor ins Reich der Edelmenschen'' ([[Vienna]], 1912) |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

== Reception == |

== Reception == |

||

Revision as of 10:31, 31 August 2015

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

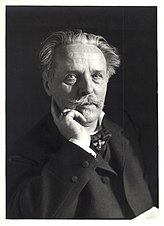

Karl Friedrich May | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 February 1842 Ernstthal, Kingdom of Saxony |

| Died | 30 March 1912 (aged 70) Radebeul, German Empire |

| Occupation | Writer; author |

| Nationality | German |

| Genre | Western, Travel Fiction, 'Heimatromane', Adventure Novels |

| Website | |

| www | |

Karl (Carl) Friedrich May (/maɪ/ MY; German: [maɪ]; 25 February 1842 – 30 March 1912) was a popular German writer, noted mainly for adventure novels set in the American Old West (best known for the characters of Winnetou and Old Shatterhand) and similar books set in the Orient and Middle East (with Kara Ben Nemsi and Hadschi Halef Omar). In addition, he wrote stories set in Latin America and his native Germany. May also wrote poetry, a play, and composed music; he was a proficient player of several musical instruments. Many of his works were filmed, adapted for the stage, turned into audio dramas or into comics. A highly imaginative and fanciful writer, May never visited the exotic places featured in his stories until late in life, at which point the clash between his fiction and reality led to a complete change in his work.

Life and career

Youth

Karl May was born the fifth child to a poor family who were weavers by trade in Ernstthal, Schönburgische Rezessherrschaften (then part of the Kingdom of Saxony). He had thirteen siblings of whom nine died in infancy.

During his school years, he received private music and composition tutelage. At twelve, May was making money at a skittle alley, where he was exposed to rough language.[1]

Delinquency

In 1856, May commenced teacher training in Waldenburg, but in 1859 was expelled for stealing six candles. After an appeal, he was allowed to continue in Plauen. Shortly after graduation, when his room mate accused him of stealing a watch, May was jailed in Chemnitz for six weeks and his license to teach was permanently revoked. After this, May worked with little success as a private tutor, an author of tales, a composer and a public speaker. From 1865 to 1869, May was jailed in the workhouse at Osterstein Castle, Zwickau. With good behaviour, May became an administrator of the prison library which gave him the chance to read widely. He planned to become an author and made a list of the works he planned to write (Repertorium C. May.) Only some came to fruition.

On his release, May continued his life of crime. He was arrested, then, when he was transported to a crime scene during a judicial investigation he escaped and fled to Bohemia, where he was detained for vagrancy. From 1870 to 1874, May was jailed in Waldheim. There he met the catholic prison's catechist Johannes Kochta, whose influence assisted May.

Early years

After his release in May 1874, May returned to his parents home in Ernstthal and began to write. In November 1874, Die Rose von Ernstthal ("The Rose from Ernstthal") was published.[2] May then became an editor in the publishing house of Heinrich Gotthold Münchmeyer in Dresden. May managed entertainment papers such as Schacht und Hütte ("Bay and Cabin") and continued to publish his own works such as Geographische Predigten ("Collected Travel Stories") (1876). May resigned in 1876[2] and was employed by Bruno Radelli of Dresden. In 1878, May became a freelance writer and in 1880, he married Emma Pollmer. Once again, May was insolvent.[2]In 1882, May returned to the employ of Münchmeyer and began the first of five large colportage novels. One of these was Das Waldröschen (1882–1884). From 1879 May was also published in Deutscher Hausschatz ("German Treasure House"), a catholic weekly journal from the press of Friedrich Pustet in Regensburg. In 1880, May began the Orient Cycle, which ran, with interruption, until 1888. May was also published in the teenage boys' journal Der Gute Kamerad ("The Good Comrade") of Wilhelm Spemann, Stuttgart. In 1887, it published Der Sohn des Bärenjägers ("Sons of the Bear Hunter"). In 1891 Der Schatz im Silbersee ("The Treasure of Silver Lake") was published. May published in other journals using pseudonyms. In all, he published over one hundred articles. In October 1888, May moved to Kötzschenbroda (a part of Radebeul) and 1891 to Villa Agnes in Oberlößnitz. In 1891, Friedrich Ernst Fehsenfeld offered to print the Deutsche Hausschatz ("Son of the Bear Hunter") stories as books. In 1892, publication of Carl May's Gesammelte Reiseromane ("Collected Travel Accounts" or "Karl May's Gesammelte Reiseerzählungen) brought financial security and recognition. May became deeply absorbed in the stories he wrote and the lives of his characters. Reader wrote to May, addressing him as the protagonists of his books. May conducted talking tours in Germany and Austria, and allowed autographed cards to be printed and photos in costume to be taken. In December 1895, May moved to the Villa Shatterhand in Alt-Radebeul, which he purchased from the Ziller Brothers.

Later years

In 1899, May travelled via Egypt to Sumatra with his servant, Sejd Hassan. In 1900, he was joined by Klara and Richard Plöhn. The group returned to Radebeul in July 1900. May demonstrated some emotional instability during his travels.[3]

Hermann Cardauns and Rudolf Lebius criticised May for his self promotion with the Old Shatterhand legend. He was also reproached his writing for the catholic Deutscher Hausschatz and several Marian calendars. There were also charges of unauthorised book publications and the use of an illegal doctoral degree. In 1902, May did receive an Doctor honoris causa from the Universitas Germana-Americana, Chicago for Im Reiche des Silbernen Löwen ("In the Realm of the Silver Lion.") [4] In 1908, Karl and Klara May spent six weeks in North America. They visited Albany, Buffalo, the Niagara Falls and friends in Lawrence. May was inspired to write Winnetou IV.

On his return, May began work on complex, allegoric texts. He considered the "question of mankind"; pacifism and the raising of humans from evil to good. Sascha Schneider provided symbolistic covers for the Fehsenfeld edition.

On 22 March 1912, May was invited by the Academic Society for Literature and Music in Vienna to present a lecture entitled Empor ins Reich der Edelmenschen ("Upward to the Realm of Noble Men"). There, he met Bertha von Suttner. Karl May died one week later on 30 March 1912. According to the register of deaths, the cause was cardiac arrest, acute bronchitis and asthma. May was buried in Radebeul East. His tomb was inspired by the Temple of Athena Nike.

Works

Introduction

May used many pseudonyms, including "Capitan Ramon Diaz de la Escosura", D. Jam, "Emma Pollmer", "Ernst von Linden", "Hobble-Frank", "Karl Hohenthal", M. Gisela, P. van der Löwen, "Prinz Muhamel Lautréamont" and "Richard Plöhn" (a friend). Most pseudonymously or anonymously published works have been identified.

For the novels set in America, May created Winnetou, the wise chief of the Apaches and Old Shatterhand, the author's alter ego and Winnetou's white blood brother. Another series of novels was set in the Ottoman Empire. The narrator-protagonist, Kara Ben Nemsi, travels with his local guide and servant Hadschi Halef Omar through the Sahara desert to the Near East, experiencing many exciting adventures.

May's writing demonstrates development from an anonymous first-person observer-narrator (for example Der Gitano, 1875) to one acquiring heroic skills and equipment, to a fully formed first-person narrator-heroe (for example, Old Shatterhand and Kara Ben Nemsi).

With few exceptions, May had not visited the places he described, but compensated successfully for his lack of direct experience through a combination of creativity, imagination, and documentary sources including maps, travel accounts and guidebooks, as well as anthropological and linguistic studies. The work of writers such as James Fenimore Cooper, Gabriel Ferry, Friedrich Gerstäcker, Balduin Möllhausen and Mayne Reid served as his models.

Non-dogmatic Christian values play an important role in May's works. May's heroes are often described as being of German ancestry. In addition, following the Romantic ideal of the "noble savage" and inspired by the writings of writers like James Fenimore Cooper or George Catlin, his Native Americans are usually portrayed as innocent victims of white law-breakers, and many are presented as heroic characters. May also wrote of the fate of other suppressed peoples. Deeply rooted in May's works is the belief that all mankind should live together peacefully; all of his main characters try to avoid taking life, except when necessary.

May deliberately avoided ethnological prejudices and wrote against public opinion (e. g. Winnetou, Durchs wilde Kurdistan, Und Friede auf Erden!). Nevertheless, there are in his work some phrasings, which today are seen as racist. For example, there are broad-brush pejorative statements about Armenians, black people, Chinese people, Irish people, Jews and mestizos. May also positively depicts some Chinese, black people and mestizos, who contradict the common clichés. In a letter to a young Jew who intended to become a Christian after reading May's books, May advised him first to understand his own religion, which he described as holy and exalted, until he was experienced enough to choose.[5]

In his later works (after 1900) May turned away from adventure fiction to write symbolic novels with religious and pacifistic content. The break is best shown in Im Reiche des silbernen Löwen where the first two parts are adventurous and the last two parts belong to the mature work.

Early work

In his early work, May wrote in a variety of genres until he showed his proficiency in travel stories.[6] During his time as editor he published many of these works within the periodicals for which he was responsible.

- Das Buch der Liebe (1876, educational work)

- Geographische Predigten (1876, educational work)

- Der beiden Quitzows letzte Fahrten (1877, unfinished)

- Auf hoher See gefangen (Auf der See gefangen, parts later revised for Old Surehand II) (1878)

- Scepter und Hammer (1880)

- Im fernen Westen (reworked in Old Firehand (1875) and later in Winnetou II)(1879)

- Der Waldläufer (reworked in "Le Coureur de Bois", a novel by Gabriel Ferry)

- Die Juweleninsel (1882)

The shorter stories of the early work can be grouped as follows, although in some works, genres overlap. Some of the shorter stories were later published in anthologies, for example, Der Karawanenwürger und andere Erzählungen (1894), Humoresken und Erzählungen (1902) and Erzgebirgische Dorfgeschichten (1903).

- Adventure fiction and early travel stories (for example, Inn-nu-woh, der Indianerhäuptling, 1875)

- Crime fiction (for example, Wanda, 1875)

- Historical fiction (for example, Robert Surcouf, 1882)

- Humorous stories (for example, Die Fastnachtsnarren, 1875)

- Series about "the Old Dessauer", Leopold I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau (for example, Pandur und Grenadier, 1883)

- Stories of villages in the Ore Mountains (for example, Die Rose von Ernstthal, 1874 or 1875)

- Natural history works (for example, Schätze und Schatzgräber, 1875)

- Letters and poems (for example, Meine einstige Grabinschrift, 1872).

Colportage novels

May wrote five large (many thousands of pages) colportage novels which he published either anonymously or under pseudonym between 1882 and 1888.

- Das Waldröschen (1882–84, a part was later revised for Old Surehand II)

- Die Liebe des Ulanen (1883–85)

- Der verlorne Sohn oder Der Fürst des Elends (1884–86)

- Deutsche Herzen (Deutsche Helden) (1885–88)

- Der Weg zum Glück (1886–88)

From 1900 to 1906, Münchmeyer's successor Adalbert Fischer published the first book editions. These were revised by third hand and published under May's real name instead of pseudonym. This edition was not authorised by May and he tried to stop the publication.[7]

Travel stories

Thirty-three volumes of Carl May's Gesammelte Reiseromane, (Karl May's Gesammelte Reiseerzählungen) were published from 1892 to 1910 by Friedrich Ernst Fehsenfeld. Most had been previously published in Deutscher Hausschatz, but some were new. The best known titles are the Orient Cycle (volumes 1 - 6) and the Winnetou-Trilogy (volumes 7 - 9). Beyond these shorter cycles, the works are troubled by chronological inconsistencies arising when original articles are revised for book editions.

- Durch Wüste und Harem (1892, since 1895 titled Durch die Wüste)

- Durchs wilde Kurdistan (1892)

- Von Bagdad nach Stambul (1892)

- In den Schluchten des Balkan (1892)

- Durch das Land der Skipetaren (1892)

- Der Schut (1892)

- Winnetou I (1893, also titled Winnetou der Rote Gentleman I)

- Winnetou II (1893, also titled Winnetou der Rote Gentleman II)

- Winnetou III (1893, also titled Winnetou der Rote Gentleman III)

- Orangen und Datteln (1893, an anthology)

- Am Stillen Ocean (1894, an anthology)

- Am Rio de la Plata (1894)

- In den Cordilleren (1894)

- Old Surehand I (1894)

- Old Surehand II (1895)

- Im Lande des Mahdi I (1896)

- Im Lande des Mahdi II (1896)

- Im Lande des Mahdi III (1896)

- Old Surehand III (1897)

- Satan und Ischariot I (1896)

- Satan und Ischariot II (1897)

- Satan und Ischariot III (1897)

- Auf fremden Pfaden (1897, an anthology)

- Weihnacht! (1897)

- Im Reiche des silbernen Löwen I (1898)

- Im Reiche des silbernen Löwen II (1898)

- Am Jenseits (1899)

May's ouvre includes some shorter travel stories, which were not published within this series (for example, Eine Befreiung in Die Rose von Kaïrwan, 1894).

After foundation of the Karl May Press in 1913, works in Karl May's Gesammelte Werke were revised (sometimes extensively) and many received new titles. Texts (other than those from Fehsenfeld Press) were added to the new series.

Stories for young readers

These stories were written from 1887 to 1897 for the magazine Der Gute Kamerad. Most of the stories are set in the Wild West, but Old Shatterhand is just a figure and not the first-person narrator as he is in the travel stories. The best known volume is Der Schatz im Silbersee. In the broadest sense the early works Im fernen Westen and Der Waldläufer belong to these category.

- Der Sohn des Bärenjägers (1887, since 1890 within Die Helden des Westens)

- Der Geist des Llano estakata (1888, since 1890 correctly titled as Der Geist des Llano estakado within Die Helden des Westens)

- Kong-Kheou, das Ehrenwort (1888/89, since 1892 titled Der blaurote Methusalem)

- Die Sklavenkarawane (1890)

- Der Schatz im Silbersee (1891)

- Das Vermächtnis des Inka (1892)

- Der Oelprinz (1894, since 1905 titled as Der Ölprinz)

- Der schwarze Mustang (1897)

- Replies to letters from readers in Der Gute Kamerad.

Mature work

May's mature work (Spätwerk) consists of the publications after his travel to the East, from 1900 onwards.[8] Many of them were published by Fehsenfeld.

- Himmelsgedanken (1900, poem collection)

- Im Reiche des silbernen Löwen III (1902)

- Erzgebirgische Dorfgeschichten (1903, anthology)

- Im Reiche des silbernen Löwen IV (1903)

- Und Friede auf Erden! (1904)

- Babel und Bibel (1906, drama)

- Ardistan und Dschinnistan I (1909)

- Ardistan und Dschinnistan II (1909)

- Winnetou IV (1910)

- Mein Leben und Streben (1910, autobiography)

- Some shorter stories belong to the mature work (for example, Schamah, 1907), and some essays and articles (for example, Briefe über Kunst, 1907).

- Legal proceedings (for example, "Karl May als Erzieher" und "Die Wahrheit über Karl May" oder Die Gegner Karl Mays in ihrem eigenen Lichte, 1902).

Other works

May was a member of the "Lyra" choir in about 1864 and composed musical works including a version of Ave Maria and Vergiss mich nicht within Ernste Klänge, 1899).[9]

During his last years, May lectured on his philosophic ideas.

- Drei Menschheitsfragen: Wer sind wir? Woher kommen wir? Wohin gehen wir? (Lawrence, 1908)

- Sitara, das Land der Menschheitsseele (Augsburg, 1909)

- Empor ins Reich der Edelmenschen (Vienna, 1912)

- Posthumous publications of fragments of stories and dramas, lyrics, musical compositions, library catalogue and letters.

Reception

Number of copies and translations

It is stated that Karl May is the “most read writer of German tongue”. The total number of copies published is about 200 millions, half of this are German copies.[10]

The first translation of May’s work was the first half of the Orient Cycle into French 1881 (just ten years after the French-German War), which was published in the French daily Le Monde[11] (published 1860–1885, not to be confused with the current daily Le Monde). Since that time May's work has been translated into more than thirty languages including Latin, Esperanto and Volapük. In the 1960s the UNESCO stated May being the most translated German writer.[10] Outside the German-speaking area he is most popular in the Czech language area, Hungary and the Netherlands. In France, Great Britain and the US he is nearly unknown.[11] In 2001 Nemsi Books Publishing Company located in Pierpont, South Dakota, opened its doors to become one of the first English publishing houses dedicated to the unabridged translations of Karl May's original work.

List of languages in which Karl May's work has been translated: Afrikaans, Brazilian, Bulgarian, Chinese, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English (British), English (American), Esperanto, Estonian, Finnish, French, Greek, Hungarian, Icelandic, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Latin, Latvian, Lithuanian, Malay, Modern Hebrew, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbo-Croatian, Slovakian, Slovene, Spanish, Swedish, Ukrainian, Vietnamese, Volapük, Yiddish[10][12]

There are also braille editions[10] and editions read for visually impaired or blind people.[13]

Influence

Karl May had a substantial influence on a number of well-known German-speaking people – and on the German population itself.[14] The popularity of his writing, and indeed, his (generally German) protagonists, are seen as having filled a lack in the German psyche which had few popular heroes until the 19th Century.[15] His readers longed to escape from an industrialised capitalist society, an escape which May offered.[16] He was noted as having "helped shape the collective German dream of feats far beyond middle-class bounds"[15] and contributed to the popular image of Native Americans in German-speaking countries.

The image of Native Americans in Germany is greatly influenced by May. The name Winnetou even has an entry in the main German dictionary Duden. The wider influence on the populace also surprised US occupation troops after World War II, who realised that thanks to Karl May, "Cowboys and Indians" were familiar concepts to local children (though fantastic and removed from reality).[14]

Many well-known German-speaking people used May's heroes as models in their childhood.[17] Physicist Albert Einstein was a great fan of Karl May's books and is quoted as having said "My whole adolescence stood under his sign. Indeed, even today, he has been dear to me in many a desperate hour..."[15] Many others have given positive statements about their Karl May reading.[18]

Adolf Hitler was an admirer, who noted that the novels "overwhelmed" him as a boy, going as far as to ensure "a noticeable decline" in his school grades.[19] According to an anonymous friend, Hitler attended the lecture given by May in Vienna in March 1912 and was enthusiastic about the event.[20] Ironically, the lecture was an appeal for peace, also heard by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Bertha von Suttner. Claus Roxin doubts the anonymous description, because Hitler had told much about May, but not that he had seen him.[21] Hitler defended May against critics in the men's hostel where he lived in Vienna, as the evidence of May's earlier time in jail had come to light; although it was true, Hitler confessed, that May had never visited the sites of his American adventure stories, this made him a greater writer in Hitler's view since it showed the author's powers of imagination. May died suddenly only ten days after the lecture, leaving the young Hitler deeply upset.[22]

Hitler later recommended the books to his generals and had special editions distributed to soldiers at the front, praising Winnetou as an example of "tactical finesse and circumspection",[23] though some note that the latter claims of using the books as military guidance are not substantiated.[15] However, as told by Albert Speer, "when faced by seemingly hopeless situations, he [Hitler] would still reach for these stories," because "they gave him courage like works of philosophy for others or the Bible for elderly people."[23] Hitler's admiration for May led the German writer Klaus Mann to accuse May of having been a form of "mentor" for Hitler.[14]

In his admiration Hitler ignored May's Christian and humanitarian approach and views completely, not mentioning his – in some novels – relatively sympathetic description of Jews and other persons of non-Northern European ancestry.

The fate of Native Americans in the United States was used during the world wars for anti-American propaganda. The National Socialists in particular tried to use May's popularity and his work for their purposes.[15] Several novels of Karl May were re-edited in an antisemitic style during the years of Nazism and led to serious misunderstandings about May's original intentions[24][failed verification] and led to his books being deemed "chauvinist" by the Communist authorities of East Germany – though this did not affect his popularity or prevent a Karl May renaissance during the 1980s.[15]

Impact on other authors

The German writer Carl Zuckmayer was intrigued by May's great Apache chief and named his daughter Maria Winnetou (* 1926).[10]

Max von der Grün reported that he read Karl May as a young boy. When asked whether reading May's books had given him anything, he answered: "No. It took something away from me. The fear of bulky books that is."[25]

Also Heinz Werner Höber, twofold Glauser prize winner, was a self-confessed follower of Karl May: "When I was about 12 years old I wrote my first novel on Native Americans which was of course from the beginning to the end completely stolen from Karl May." He had pleaded with friends to get him to Radebeul "because Radebeul meant Karl May". There he was deeply impressed by the museum and stated: "My great fellow countryman from Hohenstein-Ernstthal and his immortal heroes have never left me ever since."[26]

Adaptations

After Karl May published the whole poem Ave Maria in 1896 at least 19 other persons wrote musical versions. Other poems, especially from the collection Himmelsgedanken were set into music. As present for May Carl Ball wrote "harp clangs" for the drama Babel und Bibel. The Swiss composer Othmar Schoeck made an opera from Der Schatz im Silbersee in the age of eleven. Others wrote music inspired by May's works (e. g. around Winnetou's death).[27]

The first stage adaptation was Winnetou by Hermann Dimmler in 1919. Revisions by him and Ludwig Körner were played in the following years. After the Second World War first adaptations were conducted in Austria. In East Germany they started not before 1984. Different novel revisions are played on outdoor stages since the 1940s. The most famous Karl May Festivals are held every summer in Bad Segeberg (since 1952) and in Lennestadt-Elspe (since 1958). At both places movie actor Pierre Brice played Winnetou. Another festival is on the rock stage in Rathen, in the Saxon Switzerland near Radebeul (1940, then since 1984).[28] Many other stages in Austria and Germany show or showed plays after Karl May. In 2006 these were 14 stages. May’s own drama Babel und Bibel has not been played on a bigger stage yet.

Karl May's friends Marie Luise Droop and her husband Adolf Droop among others founded in cooperation with the Karl May Press the production company "Ustad-Film" (the name refers to May himself in Im Reiche des silbernen Löwen III/IV) in 1920. They produced three silent movies (Auf den Trümmern des Paradieses, Die Todeskarawane and Die Teufelsanbeter) after the Orientcycle in 1920, which are lost. Due to the low success "Ustad-Film" went bankrupt in the following year.[10] The first sound movie Durch die Wüste was shown in 1936. de (1958) and its sequel de (1959) were the first colour movies. Famous is the Karl May movie wave from 1962–1968, which was one of the most successful German movie series.[29] While most of the 17 movies were Wild West movies (beginning with Der Schatz im Silbersee), three were based on the Orientcycle and two on Das Waldröschen. Most of these movies were made separately by the two competitors Horst Wendlandt and Artur Brauner. Following actors played main characters in several movies of the series: Lex Barker (Old Shatterhand, Kara Ben Nemsi, Karl Sternau), Pierre Brice (Winnetou), Stewart Granger (Old Surehand), Milan Srdoč (Old Wabble) and Ralf Wolter (Sam Hawkens, Hadschi Halef Omar, André Hasenpfeffer). The film score by Martin Böttcher has also become famous and together with the landscape of Yugoslavia, where most movies were shot, it participate to the great success of the series. After the series more movies for cinema (Die Spur führt zum Silbersee, 1990) or TV (e. g. Das Buschgespenst, 1986) and TV-series (e. g. Kara Ben Nemsi Effendi, 1973) were produced. Most Karl May movies are far from the original, some even contain nothing more than May's main figures.[29]

No other German writer has more audio dramas than Karl May,[10] which have a number of about 300.[13] Günther Bibo wrote the first one (Der Schatz im Silbersee) in 1929. A greater wave was during the 1960s.[10] There are also Czech and Danish audio dramas.[13]

After the ending of the term of copyright and with the success of the Karl May movie series of the 1960s the first German comic wave occurred. A second comic wave came during the 1970s. The first and qualitative best German comic was Winnetou (# 1–8) / Karl May (# 9–52) (1963–1965). It was drawn by Helmut Nickel and Harry Ehrt and published by Walter Lehning Verlag. The most comprehensive comic was published by the press Standaard Uitgeverij. This Flemish comic Karl May was drawn by the studio of Willy Vandersteen in 87 issues from 1862–1987. Also in other countries comics were produced: e. g. Czechoslovakia (often reduced to the wild west plot), Denmark, France, Mexico, Spain and Sweden.[30]

In 1988 Der Schatz im Silbersee was read by Gert Westphal and published as audiobook. Wann sehe ich dich wieder, du lieber, lieber Winnetou? (1995) is a compendium of Karl May texts read by Hermann Wiedenroth. Since 1998 different presses (e. g. Karl May Press) have released an increasing number of about 50 audiobooks.[13] Another famous reader is movie actor Peter Sodann.

Karl May and his life were basis for screen adaptations: Freispruch für Old Shatterhand (1965, dir. Hans Heinrich) and Karl May (1974, dir. Hans-Jürgen Syberberg) as well as a 6-episode TV series Karl May (1992, dir. Klaus Überall). There are also novels with or about Karl May, e. g. Swallow, mein wackerer Mustang (1980) by Erich Loest, Vom Wunsch, Indianer zu werden. Wie Franz Kafka Karl May traf und trotzdem nicht in Amerika landete (1994) by Peter Henisch, Old Shatterhand in Moabit (1994) by Walter Püschel and Karl May und der Wettermacher (2001) by Jürgen Heinzerling. A stage adaptation is Die Taschenuhr des Anderen by Willi Olbrich.

Copies, parodies, and sequels

Already during May's lifetime he has been copied or parodied. While some just wrote similar wild west stories to participate on his literary success (e. g. Franz Treller), others even used May's name to publish their works.[31] Also today novels with May figures are published. In “Hadschi Halef Omar” (2010) Jörg Kastner describes the first contact of the titular character with Kara Ben Nemsi. Franz Kandolf wrote "In Mekka" (1923) a sequel to Am Jenseits, which is official part of Karl May's Gesammelte Werke as vol. 50. An alternative to Im Reiche des silbernen Löwen III/IV by Heinz Grill ("Die Schatten des Schah-in-Schah", 2006) has been written in the adventurous style of the first parts. As sequel to Winnetou IV May had planned Winnetous Testament. A series of eight volumes with this title has been written by Jutta Laroche and Reinhard Marheinecke. Other famous writers of sequels are Friederike Chudoba, Otto Emersleben, Thomas Jeier, Edmund Theil and Iris Wörner (Her pseudonym Nscho-tschi refers to Winnetou's sister).[31]

The 2001 film Der Schuh des Manitu by Michael Herbig is a parody on the Karl May Films of the 1960s and spoofs extensively the characters and motives of May's Winnetou trilogy.

Legacy

Asteroid 15728 Karlmay is named in his honor.[32]

Karl May institutions

Karl May Foundation

In his will, May made his second wife Klara his sole heiress. He instructed that after her death all of his property and any future earnings from his work should go to a foundation. This foundation should support the education of gifted poor people and help writers, journalists and editors, who through no fault of their own, had got into financial difficulties. One year after May's death on 5 March 1913, Klara May established the "Karl May Foundation" ("Karl-May-Stiftung"). Contributions have been made since 1917. With contracts of inheritance and wills of Klara May, the property of both went to the Karl May Foundation. Following her instructions, the foundation established a Karl May Museum to maintain the Villa "Shatterhand", the estates, the collections (the museum was founded during her lifetime) and to maintain May's tomb.[33][34] In 1960, the Karl May Foundation leaved the Karl May Press, which belonged to her by two-thirds. Thereby the press got parts of May’s properties.[34]

Karl May Press

On 1 July 1913 Klara May, Friedrich Ernst Fehsenfeld (May’s main publisher) and the jurist Euchar Albrecht Schmid established the "Foundation Press Fehsenfeld & Co." ("Stiftungs-Verlag Fehsenfeld & Co.") in Radebeul. In 1915 the name changed into "Karl May Press" ("Karl-May-Verlag" = KMV). They ended the civil disputes (e. g. about the colportage novels) and got the rights of works from others presses (e. g the colportage novels and the stories for the youth).[35] Third hand revisions of these texts were added to the series Karl May’s Gesammelte Reiseerzählungen, which was renamed to Karl May’s Gesammelte Werke (und Briefe). The existing 33 volumes of the original series also were (partly radically) revised. Until 1945 there were 65 volumes. The press nearly only publishes works of Karl May and secondary literature. Beside the Gesammelte Werke (the classical “green volumes”), which have 91 volumes today, the press has a huge reprint programme. Other targets of the young press were rehabilitation of May against literary criticism and support of the Karl May Foundation. Since the contractual quitting of Fehsenfeld in 1921 and the separation from the Karl May Foundation (as Klara May’s heir) in 1960 the press lies in hands of the Schmid family. Due to the attitudes of the authorities of the Soviet occupation zone and East Germany towards May (his works should not be printed) the press moved to Bamberg (West Germany) in 1959. After the German reunification the press has a second place of residence in Radebeul since 1996. When in 1963 the term of copyright ended the press lost its monopoly. The press started a commercialisation of May. The name "Karl May" is registered trade mark of the "Karl May Verwaltungs- und Vertriebs-GmbH", which belongs to the Karl May Press.[35]

Museums

This section may require copy editing. (March 2014) |

Radebeul

The "Karl May Museum" in Radebeul started on 1 December 1928 in "Villa Bear Fat" (Villa Bärenfett) as a museum about history and life of Native Americans. This villa was built as a log house in the garden of Villa "Shatterhand" after ideas of the widely travelled artist Patty Frank (Ernst Tobis). Karl May's collection about Native Americans, which was added by Klara May, and the whole collection of Patty Frank were joined; therefore, Frank became the first curator and got life estate in "Villa Bear Fat". During the time of the GDR the museum was renamed "Native Americans Museum of the Karl May Foundation" in 1956 and Karl May related exhibits were removed in 1962.

After rethinking of the GDR authorities the museum got its former name back and the street even was renamed "Karl May Street" in 1984. While "Villa Bear Fat" further on contains the exhibition about Native Americans, where the fireplace room today is used for events, Villa "Shatterhand" shows an exhibition about Karl May since 1985. Beside the library, which can be used for research, the work room and parlour (so called "Sascha Schneider Room") are originally arranged. Among others the replicas of the "famous guns" and a bust of Winnetou are shown. Opposite to Villa "Shatterhand" May's fruit garden has become the "Karl May Grove" ("Karl-May-Hain").[36]

Hohenstein-Ernstthal

The “Karl May House” (“Karl-May-Haus”) is the about 300 year old weaver house, where May was born. During the May renaissance in the GDR it has become a memorial and museum since 12 March 1985. Beside the permanent exhibition about May's life rebuild rooms like a weaver chamber and non-German book editions are shown. The garden has been arranged according to May's description in his biography. Opposite the house lies the "International Karl May Heritage Center" ("Karl-May-Begegnungsstätte"), which is used for events and special exhibitions. In Hohenstein-Ernstthal, which is called "Karl May Home Town" since 1992, every May related place has a commemorative plaque. These places are connected by a "Karl May Path" ("Karl-May-Wanderweg"). Outside the city lies the "Karl May Cave" ("Karl-May-Höhle"), where May found shelter during his criminal time.[37]

Societies

Some associations have been founded during Karl May’s lifetime, e. g. “Karl May Clubs” in the 1890s.[38] Today, various work groups, societies, and clubs are devoting their activities to Karl May's life and work, and organize related events. While early associations often understood their role as rendering homage to the writer or defending him against critics, they focus today more on research.[39] Most societies are in German-speaking areas (e. g. booster clubs of the museums), but some can also be found in the Netherlands, Australia and Indonesia. While the societies are responsible for the release of most Karl May-related periodicals (e. g Der Beobachter an der Elbe, Karl-May-Haus Information, Wiener Karl-May-Brief, Karl May in Leipzig), the magazine Karl May & Co. is published independently.

The "Karl May Society" ("Karl May Gesellschaft e.V." = KMG) is the largest society with approximately 1800 members. The KMG was founded on 22 March 1969. One of its main objectives is to conduct research on Karl May's life and work and to promote his recognition in the official history of literature and the general public.[40] Among the various publications of the society are the Jahrbuch, the Mitteilungen, the Sonderhefte der Karl-May-Gesellschaft, and the KMG-Nachrichten as well as a huge reprint programme. Since 2008 and in cooperation with the Karl May Foundation and the Karl May Press, the KMG publishes the critical edition of "Karl Mays Werke". This project had been initiated by Hans Wollschläger and Hermann Wiedenroth in 1987. After initial disruptions and changes also regarding the printing[7] the project is now conceptualized to more than 99 volumes.[41]

See also

References

- Grams, Grant: Was Karl May in Canada? The works of Max Otto: A German Writer's "Absurb Picture of Canada" in Yearbook of German-American Studies, Volume 42 2007, pp. 69–83.

- Grams, Grant: "This terrible Karl May" in the Wild West, Karl B. Schwerla: Kanada I'm Faltboot, in Alberta History Volume 56 No.1 2008, pp. 10–13.

- ^ May K. Mein Leben und Streben

- ^ a b c Sudhoff and Steinmetz Karl-May-Chronik I

- ^ Bartsch E. and Wollschläger H. Karl May's Orientreise 1899-1900. in Karl May: In fernen Zonen. Verlag, Bamberg and Radebeul, 1999.

- ^ Heermann C. Winnetous Blutsbruder. Verlag, Bamberg and Radebeul, 2002.

- ^ May K. Letter to Herbert Friedländer (13 April 1906) in Wohlgschaft: Karl May, Leben und Werk, p. 1555f.

- ^ Lowsky M. Karl May Metzler, Stuttgart, 1987, vol 231 p38.

- ^ a b Wehnert, Jürgen: Der Text. In Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 116–130.

- ^ Schmid E. A. Gestalt und Idee. p 367-420 in Karl May. ICH 39th Edition Verlag, Bamberg, 1995

- ^ Kühne H. and Lorenz C. F. Karl May und die Musik. Verlag, Bamberg and Radebeul, 1999.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Petzel, Michael & Wehnert, Jürgen: Das neue Lexikon rund um Karl May. Lexikon Imprint Verlag, Berlin 2002.

- ^ a b von Thüna, Ulrich: Übersetzungen. In Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 519–522.

- ^ Books by Karl May in Estonian in National Library of Estonia

- ^ a b c d Karl May audio drama database

- ^ a b c Ich bin ein Cowboy – The Economist, 24 May 2001

- ^ a b c d e f Tales Of The Grand Teutons: Karl May Among The Indians – The New York Times, 4 January 1987

- ^ The American Indian in the Great War, Real and Imagined – Camurat, Diane

- ^ Müller, Erwin: Aufgespießt. In several issues of KMG-Nachrichten

- ^ Karl May Template:De icon

- ^ Hitler's Mein Kampf attribution of his poor grades in secondary school (his primary school marks, in grades first through fifth, had been quite good in general) to his fascination with May is not entirely reliable. There were a number of factors which contributed: attendance at a larger school in Linz, segregation of classes by subject matter rather than by age, and more difficult subject matter are identified by Kershaw (Adolf Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris, chapter 1).

- ^ (Anonymus): Mein Freund Hitler Within: Moravsky ilustrovany zpravodaj. 1935, No. 40, p. 10f.

- ^ Roxin, Claus: Letter from 24 February 2004. Cited within: Wohlgschaft: Karl May – Leben und Werk, p. 2000.

- ^ Hamman, Brigette (1999). Hitler's Vienna: A Dictator's Apprenticeship. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 382–85. ISBN 0-19-512537-1.

- ^ a b Mein Buch – Grafton, Anthony, The New Republic, December 2008

- ^ Harder, Ralf: Mißbraucht im Dritten Reich

- ^ Thor-Heyerdahl-Gymnasium – Anecdotes Template:De icon

- ^ Eik, Jan: Der Mann, der Jerry Cotton war. Erinnerungen des Bestsellerautors Heinz Werner Höber. Das Neue Berlin, Berlin, 1996. EAN 9783359007999

- ^ Kühne, Hartmut: Vertonungen. In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 532–535.

- ^ Hatzig, Hansotto: Dramatisierungen. In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 523–526.

- ^ a b Hatzig, Hansotto: Verfilmungen. In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 527–531.

- ^ Petzel, Michael: Comics und Bildergeschichten. In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 539–545.

- ^ a b Wehnert, Jürgen: Fortsetzungen, Ergänzungen und Bearbeitungen. In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 509–511.

- ^ "15728 Karlmay", Jet Propulsion Laboratory – Small-Body Database, NASA, retrieved 16 October 2012

- ^ Schmid, Euchar Albrecht: Karl Mays Tod und Nachlaß. pp. 352ff., 362ff. In: Karl May. „ICH“ (39th Edition). Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg, 1995, pp. 327–365.

- ^ a b Wagner, René: Karl-May-Stiftung (Radebeul). In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 549–551.

- ^ a b Wehnert, Jürgen: Der Karl-May-Verlag. In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 554–558. Cite error: The named reference "WehnertKMV" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Wagner, René: Karl-May-Museum (Radebeul). In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 547–549.

- ^ Neubert, André: Karl-May-Haus (Hohenstein-Ernstthal). In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 546–547.

- ^ Wohlgschaft: Karl May – Leben und Werk. p. 1029

- ^ Heinemann, Erich: Organe und Perspektiven der Karl-May-Forschung. In: Ueding: Karl-May-Handbuch, pp. 559–564.

- ^ Satzung der Karl-May-Gesellschaft e.V. 02.03.2010.

- ^ Edition plannings

Literature

Works

- Karl Mays Werke: historisch-kritische Ausgabe. Für die Karl-May-Stiftung herausgegeben von Hermann Wiedenroth und Hans Wollschläger. F. Greno, Nördlingen 1987 ff. / then by Haffmans: Zürich / then by Bücherhaus: Bargfeld 1993–2007 / now: Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg and Radebeul.

- (this translates in English as: Karl May's Works: historical critical edition. On behalf of the Karl May Foundation edited by Hermann Wiedenroth and Hans Wollschläger / changed publisher 3 times.)

- The Catalogue of the German National Library presently shows 58 entries under the name of this project, including improved re-editions, supplementary volumes, edited documents etc.

- Mein Leben und Streben (autobiography). Freiburg i. Br., Friedrich Ernst Fehsenfeld, 1910. Reprint: Hildesheim and New York, Olms Presse, 1975 (third edition 1997), with preface, comments, epilogue, index for subjects, persons and geographical names by Hainer Plaul.

- Online version in English, translated by Gunther Olesch in 2000 under the title My Life and My Efforts (on the web site of the Karl May Society).

- Another translation was published in print by Michael Michalak under the title My Life and My Mission (Nemsi Books Publishing 2007, 199 pages, ISBN 0-9718164-7-6, and ISBN 978-0-9718164-7-3).

Secondary literature

- Bugmann, Marlies: Savage To Saint, The Karl May Story. BookSurge Publishing, 2008, ISBN 1-4196-5585-X, ISBN 978-1-4196-5585-2 (First English biography of Karl May).

- Frayling, Christopher: Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone. Routledge, London and Boston 1981; revised edition I.B.Taurus, London and New York 2006, ISBN 978-1-84511-207-3.

- Plaul, Hainer: Illustrierte Karl-May-Bibliographie. Unter Mitwirkung von Gerhard Klußmeier. Saur, Munich, London, New York, Paris 1989, ISBN 3-598-07258-9 (illustrated Bibliography in Template:De icon).

- Sammons, Jeffrey L.: Ideology, nemesis, fantasy: Charles Sealsfield, Friedrich Gerstäcker, Karl May, and other German novelists of America. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1998, ISBN 0-8078-8121-X.

- Sudhoff, Dieter & Steinmetz, Hans-Dieter: Karl-May-Chronik (5 Volumes + companion book). Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg and Radebeul 2005–2006, ISBN 3-7802-0170-4 (Chronicle in Template:De icon).

- Ueding, Gert (Editor): Karl-May-Handbuch. Second enlarged and revised edition. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2001, ISBN 3-8260-1813-3 (Handbook in Template:De icon).

- Wohlgschaft, Hermann: Karl May – Leben und Werk (3 Volumes). Bücherhaus, Bargfeld 2005, ISBN 3-930713-93-4 (Most extensive biography in Template:De icon; Online-Version of first edition).

- Wollschläger, Hans: Karl May. Grundriß eines gebrochenen Lebens. (First edition under a different title 1965;) Revised edition Diogenes, Zürich 1976; latest edition Wallstein, Göttingen 2004 (303 pp.), ISBN 3-89244-740-3 (Major and path-breaking biography in Template:De icon. This biography by Wollschläger (1935–2007), who was himself an esteemed author of fiction and non-fiction, was historically important to establish Karl May as an author "to be taken serious" even by academically educated readers).

- Helmut Schmiedt: Karl May oder Die Macht der Phantasie. C.H. Beck Verlag, München 2011 ISBN 978-3-406-62116-1. (Template:De icon)

External links

Life and works

- Karl May Gesellschaft (K. M. Society) Literature of the KMG, biography, bibliography of the secondary literature, lexicon of figures, and works in full text / English Homepage of the Society.

- The 100th Anniversary of Karl May's Death: Literary Genius or Man of Legendary Hubris?

- Literature by and about Karl May in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by Karl May at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Karl May at the Internet Archive

- Works by Karl May at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Karl May bibliography by Wolfgang Hermesmeier Template:De icon.

- Bibliographic database of editions since 1963 Template:De icon.

- Karl Friedrich May Papers at Gettysburg College.

- Karl-May-Wiki Template:De icon.

- BBC Radio 4: Radio report on the importance of Karl May for Germans in general and especially for Hitler.

Institutions

- Karl May Foundation Template:De icon.

- Karl May Press Template:De icon.

- Karl May Museum in Radebeul Template:De icon (Flyer in English).

- Karl May House in Hohenstein-Ernstthal (Museum) Template:De icon.

- Karl May Society ( see above).

- Overview of German and international societies Template:De icon.

Compositions by Karl May

- Free scores by Karl May at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Karl May in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)