Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum: Difference between revisions

→Offering formulas in the tomb: more precise reference for Anubis in the formula |

→References: refs for new section on funeral procession |

||

| Line 196: | Line 196: | ||

<ref name="Arnold1999b">{{cite book|last1=Arnold|first1=Dorothea|editor1-last=Fuerstein|editor1-first=Carol|title=Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids|date=1999|publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art (exhibition catalog)|location=New York|isbn=0-87099-906-0|pages=352-353|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Egyptian_Art_in_the_Age_of_the_Pyramids|chapter=Lion-Headed Goddess Suckling King Niuserre (Cat. No. 118)}}</ref> |

<ref name="Arnold1999b">{{cite book|last1=Arnold|first1=Dorothea|editor1-last=Fuerstein|editor1-first=Carol|title=Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids|date=1999|publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art (exhibition catalog)|location=New York|isbn=0-87099-906-0|pages=352-353|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Egyptian_Art_in_the_Age_of_the_Pyramids|chapter=Lion-Headed Goddess Suckling King Niuserre (Cat. No. 118)}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="Baines1983">{{cite journal|last1=Baines|first1=John|title=Literacy and Ancient Egyptian Society|journal=Man|date=1983|volume=18|issue=3|doi=10.2307/2801598|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/2801598|accessdate=24 January 2017}}</ref> |

<ref name="Baines1983">{{cite journal|last1=Baines|first1=John|title=Literacy and Ancient Egyptian Society|journal=Man|date=1983|volume=18|issue=3|doi=10.2307/2801598|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/2801598|accessdate=24 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Baines1985> {{cite journal|last1=Baines|first1=John|title=Egyptian Twins|journal=Orientalia|date=1985|volume=54|issue=4|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/43075353|accessdate=4 February 2017}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Baines2014">{{cite book|last1=Baines|first1=John|editor1-last=Ghitta|editor1-first=Ovidu|title=Historia 59|date=2014|publisher=Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai|location=Cluj-Napoca, Romania|pages=4, Fig. 4|url=http://studia.ubbcluj.ro/download/pdf/869.pdf|accessdate=26 January 2017|chapter=Not only with the dead: banqueting in ancient Egypt}}</ref> |

<ref name="Baines2014">{{cite book|last1=Baines|first1=John|editor1-last=Ghitta|editor1-first=Ovidu|title=Historia 59|date=2014|publisher=Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai|location=Cluj-Napoca, Romania|pages=4, Fig. 4|url=http://studia.ubbcluj.ro/download/pdf/869.pdf|accessdate=26 January 2017|chapter=Not only with the dead: banqueting in ancient Egypt}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="Bard">{{cite book|last1=Bard|first1=Kathryn|title=An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt|date=2007|publisher=Blackwell|location=Malden, MA|isbn=978-1-4051-1149-2}}</ref> |

<ref name="Bard">{{cite book|last1=Bard|first1=Kathryn|title=An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt|date=2007|publisher=Blackwell|location=Malden, MA|isbn=978-1-4051-1149-2}}</ref> |

||

| Line 201: | Line 202: | ||

<ref name=BMFA>{{cite web|last1=Museum of Fine Arts Boston|first1=museum record: gold cylinder seal, reign of Djedkare Isesi, Dyn. 5. Accession No. 68.115|title=Seal of Office|url=http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/seal-of-office-150473|website=Museum of Fine Arts Boston|publisher=Author.|accessdate=20 January 2017}}</ref> |

<ref name=BMFA>{{cite web|last1=Museum of Fine Arts Boston|first1=museum record: gold cylinder seal, reign of Djedkare Isesi, Dyn. 5. Accession No. 68.115|title=Seal of Office|url=http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/seal-of-office-150473|website=Museum of Fine Arts Boston|publisher=Author.|accessdate=20 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Barta2001>{{cite book|last1=Barta|first1=Miroslav|title=Abusir V: The Cemeteries at Abusir South I|date=2001|publisher=Czech Inst. of Egyptology|location=Prague|isbn=80-86277-18-6|url=http://cegu.ff.cuni.cz/cs/veda-a-vyzkum/elektronicke-publikace/|accessdate=18 January 2017}}</ref> |

<ref name=Barta2001>{{cite book|last1=Barta|first1=Miroslav|title=Abusir V: The Cemeteries at Abusir South I|date=2001|publisher=Czech Inst. of Egyptology|location=Prague|isbn=80-86277-18-6|url=http://cegu.ff.cuni.cz/cs/veda-a-vyzkum/elektronicke-publikace/|accessdate=18 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Booth2015>{{cite book|last1=Booth|first1=Charlotte|title=In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians|date=2015|publisher=Amberley|location=Stroud, UK|isbn=978-1445643-519}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Borchardt1913>{{cite book|last1=Borchardt|first1=Ludwig|title=Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Sahure 2|date=1913|publisher=Hinrich|location=Leipzig|url=http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/borchardt1910ga|accessdate=27 January 2017|language=German}}</ref> |

<ref name=Borchardt1913>{{cite book|last1=Borchardt|first1=Ludwig|title=Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Sahure 2|date=1913|publisher=Hinrich|location=Leipzig|url=http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/borchardt1910ga|accessdate=27 January 2017|language=German}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="Brovarski1996">{{cite book|last1=Brovarski|first1=Edward|editor1-last=Der Manuelian|editor1-first=Peter|title=Studies in Honor of William Kelly Simpson|date=1996|publisher=Museum of Fine Arts Boston|isbn=0-87846-390-9|chapter=An Inventory List from Covington's Tomb}}</ref> |

<ref name="Brovarski1996">{{cite book|last1=Brovarski|first1=Edward|editor1-last=Der Manuelian|editor1-first=Peter|title=Studies in Honor of William Kelly Simpson|date=1996|publisher=Museum of Fine Arts Boston|isbn=0-87846-390-9|chapter=An Inventory List from Covington's Tomb}}</ref> |

||

| Line 222: | Line 224: | ||

<ref name="Hagen2007">{{cite book|last1=Hagen|first1=Rose-Marie & Ranier|editor1-last=Wolf|editor1-first=Norbert|title=Egypt Art|date=2007|publisher=Taschen|location=Los Angeles|isbn=978-3-8228-5458-7|pages=9-10}}</ref> |

<ref name="Hagen2007">{{cite book|last1=Hagen|first1=Rose-Marie & Ranier|editor1-last=Wolf|editor1-first=Norbert|title=Egypt Art|date=2007|publisher=Taschen|location=Los Angeles|isbn=978-3-8228-5458-7|pages=9-10}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Janosi1999>{{cite book|last1=Janosi|first1=Peter. "The Tombs of Officials"|title=Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids|date=1999|publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art (exhibition catalog)|location=New York|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Egyptian_Art_in_the_Age_of_the_Pyramids|accessdate=10 January 2017}}</ref> |

<ref name=Janosi1999>{{cite book|last1=Janosi|first1=Peter. "The Tombs of Officials"|title=Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids|date=1999|publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art (exhibition catalog)|location=New York|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Egyptian_Art_in_the_Age_of_the_Pyramids|accessdate=10 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Jones1995>{{cite book|last1=Jones|first1=Dilwyn|title=Boats|date=1995|publisher=University of Texas Press|location=Austin|isbn=0-292-74039-5}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Kammerzell2001>On the Old Kingdom sound correspondences of Egyptological transcription symbols cf. Frank Kammerzell, Old Egyptian and Pre-Old Egyptian: Tracing Linguistic Diversity in Archaic Egypt and the Creation of the Egyptian Language, in: ''Texte und Denkmäler des ägyptischen Alten Reiches'', ed. by Stephan J. Seidlmayer, Thesaurus Lingua Aegyptiae 3, Achet 2001, p. 230. {{cite web|url=http://www.archaeologie.hu-berlin.de/aegy_anoa/publications/kammerzell_old-egyptian-and-pre-old-egyptian/at_download/file |title=Archived copy |accessdate=2014-08-23 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140826120735/http://www.archaeologie.hu-berlin.de/aegy_anoa/publications/kammerzell_old-egyptian-and-pre-old-egyptian/at_download/file |archivedate=2014-08-26 |df= }}</ref> |

<ref name=Kammerzell2001>On the Old Kingdom sound correspondences of Egyptological transcription symbols cf. Frank Kammerzell, Old Egyptian and Pre-Old Egyptian: Tracing Linguistic Diversity in Archaic Egypt and the Creation of the Egyptian Language, in: ''Texte und Denkmäler des ägyptischen Alten Reiches'', ed. by Stephan J. Seidlmayer, Thesaurus Lingua Aegyptiae 3, Achet 2001, p. 230. {{cite web|url=http://www.archaeologie.hu-berlin.de/aegy_anoa/publications/kammerzell_old-egyptian-and-pre-old-egyptian/at_download/file |title=Archived copy |accessdate=2014-08-23 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140826120735/http://www.archaeologie.hu-berlin.de/aegy_anoa/publications/kammerzell_old-egyptian-and-pre-old-egyptian/at_download/file |archivedate=2014-08-26 |df= }}</ref> |

||

<ref name="Kemp2006">{{cite book|last1=Kemp|first1=Barry|title=Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization|date=2006|publisher=Routledge|location=New York|isbn=978-0-415-23550-1|edition=2nd}}</ref> |

<ref name="Kemp2006">{{cite book|last1=Kemp|first1=Barry|title=Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization|date=2006|publisher=Routledge|location=New York|isbn=978-0-415-23550-1|edition=2nd}}</ref> |

||

| Line 236: | Line 239: | ||

<ref name="Pinch2002">{{cite book|last1=Pinch|first1=Geraldine|title=Egyptian Mythology: A Guide...|date=2002|publisher=Oxford|location=New York|isbn=978-0-19-517024-5|pages=153–155|edition=pbk.}}</ref> |

<ref name="Pinch2002">{{cite book|last1=Pinch|first1=Geraldine|title=Egyptian Mythology: A Guide...|date=2002|publisher=Oxford|location=New York|isbn=978-0-19-517024-5|pages=153–155|edition=pbk.}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=PorterMoss>{{cite book|last1=Porter & Moss|editor1-last=Malek|editor1-first=Jaromir|title=Topographical Biography III: Memphis, Part 2: Saqqara to Dahshur|date=1981|publisher=Griffith Institute|location=Oxford|pages=641–644, Plan LXVI|edition=revised|url=http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/topbib/pdf/pm3-2.pdf|accessdate=9 January 2017}}</ref> |

<ref name=PorterMoss>{{cite book|last1=Porter & Moss|editor1-last=Malek|editor1-first=Jaromir|title=Topographical Biography III: Memphis, Part 2: Saqqara to Dahshur|date=1981|publisher=Griffith Institute|location=Oxford|pages=641–644, Plan LXVI|edition=revised|url=http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/topbib/pdf/pm3-2.pdf|accessdate=9 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Reeder2000>{{ cite journal |last1=Reeder|first1=Greg|title=Same-Sex Desire, Conjugal Constructs, and the Tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep|journal=World Archaeology|date=2000|volume=32|issue=2-Queer Archaeologies|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/827865|accessdate=4 February 2017}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Regulski2009>{{cite journal|last1=Regulski|first1=Ilona|title=Investigating a new Dynasty 2 necropolis at South Saqqara|journal=British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan|date=2009|volume=13|issue=2009|url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/Regulski2009_b.pdf|accessdate=23 January 2017}}</ref> |

<ref name=Regulski2009>{{cite journal|last1=Regulski|first1=Ilona|title=Investigating a new Dynasty 2 necropolis at South Saqqara|journal=British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan|date=2009|volume=13|issue=2009|url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/Regulski2009_b.pdf|accessdate=23 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

<ref name=Rice>{{cite web|last1=Anonymous (19th century map)|title=Pyramids and Tombs of Sakkara [and] Group of Pyramids of Sakkara [and] Pyramids and Tombs of Abusir|url=https://scholarship.rice.edu/handle/1911/9312|website=Travelers of the Middle East|publisher=Rice University|accessdate=24 January 2017}}</ref> |

<ref name=Rice>{{cite web|last1=Anonymous (19th century map)|title=Pyramids and Tombs of Sakkara [and] Group of Pyramids of Sakkara [and] Pyramids and Tombs of Abusir|url=https://scholarship.rice.edu/handle/1911/9312|website=Travelers of the Middle East|publisher=Rice University|accessdate=24 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:59, 4 February 2017

Khnumhotep (pronunciation: xaˈnaːmaw-ˈħatpew) and Niankhkhnum (pronunciation: nij-daˌnax-xaˈnaːmaw) [1]: 230 were ancient Egyptian royal servants. They shared the title of Overseer of the Manicurists in the Palace of King Nyuserre Ini, sixth pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty, reigning during the second half of the 25th century BCE. They were buried together and are listed as "royal confidants" in their joint tomb. [2]: 98

Family

Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum were ancient Egyptian royal servants and are believed by some to be the first recorded same-sex couple in history.[3]: 96ff The proposed homosexual nature of Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum is based on depictions of the two men standing nose to nose and embracing.[4][5] Niankhkhnum's wife, depicted in a banquet scene, was almost completely erased in ancient times, and in other pictures Khnumhotep occupies the position usually designated for a wife. Their official titles were "Overseers of the Manicurists of the Palace of the King".[6]: 342 Critics argue that both men appear with their respective wives and children, suggesting the men were brothers, rather than lovers.[7][8]: 88

Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum are depicted in the tomb with their respective families. It has been proposed that they were the sons of Khabaw-khufu and Rewedzawes. They appear to have had three brothers named Titi, Nefernisut, and Kahersetef. Three possible sisters are also attested. They are named Neferhotep-hewetherew, Mehewet and Ptah-heseten. Niankhkhnum's wife was named Khentikawes. The couple appear in the tomb with three sons named Hem-re, Qed-unas and Khnumhezewef, and three daughters, Hemet-re, Khewiten-re and Nebet. At least one grandson is attested, Irin-akheti, the son of Hem-re and his wife, Tjeset.

Khnumhotep had a wife by the name of Khenut. Khnumhotep and Khenut had at least five sons named Ptahshepses, Ptahneferkhu, Kaizebi, Khnumheswef and Niankhkhnum—the younger named after his uncle, as well as a daughter named Rewedzawes.[7]

Titularies

The tomb features numerous lists of titles and epithets, either honoring the deceased or held during life, as well as titles for persons who appear in the funeral procession scene where the legal text is found. For the tomb owners, these may be condensed as follows:[9][Notes 1][Notes 2][Notes 3]

Held by either or both men

- m-r jr ant pr aA "overseer of manicurists (literally, 'those who do fingernails') in the palace." pr aA means "the great house,"[10]: 34 the name for the center of power, at Memphis during the Old Kingdom. In the later story of Sinuhe, after 12th Dynasty rulers of the Middle Kingdom had fixed the political capital near the Fayum Oasis at Itjtawy, the palace was called the Xnw "interior."[9]: Szene 13 [11]: 59

- sHD jr ant pr aA "inspector of manicurists in the palace"[9]: Szene 15

- Hrj sStA "guardian of secrets" (As a verb, sStA is causative, so the term would refer to the process of making secrets. For more on this title, which originates from the Giza necropolis, see subsection on Hrj sStA below or consult the reference.)[12]: 75 [9]: Szene 13

- rx nswt "king's acquaintance"[citation needed]

- zXAw nswt "king's scribe"[citation needed]

- mHnk nswt "confidant of the king"[9]: Szene 13, 15

- jr xt nswt "keeper of the king's things"[9]: Szene 23

- mrr nb.f "one who is beloved of his lord"[citation needed]

- Hm-nTr ra m Szp jb ra "sun priest in the (place where the sun-god) Ra's heart receives welcome," that is, in Nyuserre's solar temple at Abu Ghurab[13]: 808 [9]: Szene 23

- wab mn swt nj-wsr-ra "purity attendant of the enduring places of Nyuserre" (a cleaner-priest in this king's pyramid complex at Abusir). A peculiar hieroglyphic grapheme in this title, a device of three seat signs (denoting plural noun) followed by a pyramid, is seen on a gold seal purportedly found in Turkey, a demonstration of official use of a pyramid establishment title for signing documents.[9]: Szene 23, [14]

- wab nswt "one who purifies the king." (a personal priest to the king)[9]: Szene 13

- nb jmAx nTr aA "lord of those who are honored before the great god" (an aspirational title signifying donations to the individual's mortuary estate from the king; see subsection on jmAx below)[9]: Szene 13

- jmAx nTr aA "one who is honored before the great god" (a posthumous title)[9]: Szene 31

While items empaneled here are representative, they do not exhaust the set. These titles related to each man's job in the bureaucratic state, but more importantly, signified rank and power relative to other officials at court.[15][12]: 60, 72–73 They also help date burials, as changes in the mix of titles in circulation and in the way they were spelled are well-documented. The wab-priests, armed with brooms, handled cleanliness, ritual purity, and portage of offerings in areas of the temple outside the inner sanctuary where the god's cult statue was kept and where the higher, Hm nTr priests worked.[16]: 20–21, 26 We see that a Hm nTr at the solar temple was not above putting in stints as a humbler wab at the pyramid complex—if his titulary reflects his actual work, a matter deeply in question.[17]: 55, 359

Translation into modern languages

Translation of Egyptian terms varies considerably between authors: Raymond O. Faulkner's 1962 concise dictionary (p. 239) renders titulary noun sHD as "inspector" based on New Kingdom historical sources, with added question mark. Ranier Hannig, from period sources, calls the sHD an "Untervorsteher" (subordinate official),[13]: 1178 of rank lower than the m-r; in particular, the sHD jrj.w an.wt pr aA who supervises manicurists in the palace is an Untervorsteher.[13]: 1179 Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep held the title m-r "overseer" of the manicurists in addition to their sHD stations. Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae has followed Hannig on this issue, but cautions that its text translations, here taken from Moussa & Altenmüller's 1977 publication of the tomb, are not definitive. Baud considers emerging local overlordships and subdivision of the bureaucracy in the Old Kingdom the primary phenomena responsible for multiple titles pertaining to one occupational field.[15]: 91–94 [Notes 4]

Uncertainty increases when abstract concepts are at hand: Old Kingdom pyramids were named using constructions scholars haven't yet parsed completely, so that modern book translations only gloss the original meanings. For instance, to English-speaking ears, the near-synonyms "abide" and "endure" display a species difference within the genus of "things which survive a long time," the former more animate than the latter, yet both can be used to translate the word mn found in 5th and 6th Dynasty pyramid names. [18]: 73

The religious and mortuary establishments

We should note the two temples mentioned, the solar and the one beside the pyramid, are distinct, about a mile (1.5 km) apart in the Abusir-Abu Ghurab necropolis district southwest of modern Cairo, and, like most cemeteries, sited in the desert just beyond reach of the annual Nile flood. Each 5th Dynasty pyramid furthermore came with two temple enclosures, a mortuary establishment in the shadow of the pyramid itself and a valley temple at the edge of the cultivated land, a causeway connecting these. The solar temple had similar auxiliary structures.[19]: 93–95 [Notes 5][20]

Suspicion that Nyuserre, the most prolific of the 5th-Dynasty monument builders, usurped his predecessor Neferirkare's valley temple and causeway for his own pyramid project arises, even in popular literature, as his causeway runs directly toward Neferirkare's pyramid a considerable distance before detouring, a thing no other causeway at Abusir does.[21]: 33, 121 [22]: 151 [23][20]: map Such usurpation is common, and not necessarily directed at promoting self in lieu of family line: New Kingdom practice of Thutmose III while erasing Hatshepsut’s cartouches at Medinet Habu was to substitute not his own cartouches, but those of Thutmoses I and II, his immediate ancestors.[24]: 12 [25]: 267 Ladislav Bareš, of the Czech Egyptological school which has excavated at Abusir and Saqqara over decades, believes Neferirkare was Nyuserre’s father, and that the elder died leaving mortuary construction unfinished.[26]: xiv, 1–3 In this case, completion of family dynastic monumental statements, not usurpation, would be the applicable motive. (Observe that the 5th and most other numbered dynasties in Egypt cover more than one family line.) Ćwiek demurs, but places 'usurpation' in single quotes.[21]: 33 The result was an unusual L-shaped floor plan in a location shoehorned between existing pyramids and mastabas, a problem the sun temple escaped.[27]: 62–65

The Hrj sStA and control of information by the state

The title Hrj sStA "keeper of the secrets" is attested for 13 individuals during the Old Kingdom, at least once elaborated to the form Hr sStA mdw-nTr "keeper of the secrets of the god's words," meaning the hieroglyphic language used on monuments.[12]: 75 [10]: 44 In contrast with the hieratic script used for everyday record-keeping, already an elite activity no more than one percent of the population engaged in, the content of hieroglyphic texts was closely controlled property of the state and permission from the king was probably required for inscriptions in one's tomb, as we see in a royal authorization for Rawer, an official under Neferirkare buried at Giza, to do so. Indeed, the 5th Dynasty marks the appearance in quantity of extended prose documents carrying legal force.[10]: 6 [28]: 584 [17]: 79–81

The Pyramid Texts (in prefatory stages of development during Nyuserre's reign, then first inscribed in and around the burial chamber of King Unas) were reserved for royals only; a democratization of magic spells for the afterlife which would yield the Coffin Texts and Book of the Dead remained yet to come, although physical offering goods royal mortuary texts called for could be listed by name and icon in private tombs, and offering formulas for non-royal burials were available. The Hrj sStA was at times in charge of enforcing these rules, or at least the will of the king expressed through the vizier, as shown by the 6th-Dynasty tomb of Khenu at Deir el-Gabrawi: Khenu held the title Hrj sStA n Hwt wrt "chief of secrets in the great hut," the vizier's bureau.[29]: 1 In parallel with the rise of legal documents, the Pyramid Texts increased the complexity of religion, adding the Osirian underworld to the deceased's experience in complementarity with already-prevalent solar themes.[30]: 98–99, 102–103 [31]: 192–198 [10]: 322

The jmAx concept as proximity to king and god, in life and hereafter

jmAx nTr aA "honored one near the great god" is basically a euphemism for "dead," appearing frequently in tombs and on slab stelae, even though it, like the word (and goddess) mAat, evokes a multifarious idealization of relationships between social and cosmological ranks.

Epithets beginning with jmAx are common throughout Egyptian history beginning with Dynasty 4,[18]: 194 tending toward flower and specificity in later periods. An official could possess several. For instance, Niankhnum and Khnumhotep were both jmAx "honored" xr nswt "before the king" as well as before the nTr aA "great god," this time presumably in life; however king and god themselves can be one and the same, especially upon death, as Amenemhat I would be in the early Middle Kingdom story of Sinuhe.[11]: 59 The goal of kingship, after maintaining social order (mAat) in Egypt, was to ascend and unite with the sun disk of Heliopolitan theology originating in the Old Kingdom and maintained, off and on, until the arrival of Christianity.[10]: 121 Since jmAx can also be translated as "provided for," the connection an official's tomb holds with royal subsidy is made implicit, although some authors believe the officials built their tombs using their own resources once the 4th Dynasty (and Khufu's largess at Giza) ended.[30]: 103 [32]: 14

The efficacy of jmAx status in garnering support from the living world is unknown, although the title holders were expected to confer favors in return, from the necropolis as beings in their afterlife corpora, denoted by the word Ax "akh" and perceived as effective against illness or through dreams. Beyond doubt it was an important matter: Egyptians wrote letters to the dead, an activity which peaked during the Old and Middle Kingdoms.[31]: 42 Royal mortuary cults continued operations at Abusir through the end of the 6th Dynasty; maintenance for private cults being less certain.[26]: 1–3 Saqqara was still receiving interments of officials in the Middle and New Kingdom periods,[33][34] where a hypothesis that burial grounds were segregated according to professional line has been advanced; this is uncertain, as is whether the pattern was based on older precedent.[35]: xiv, 1–3 The 1st Dynasty drew such a pattern in stark outlines: Kings chose Abydos while the dignitaries were buried at Saqqara, but not so in the 2nd, when royal burials at Saqqara alongside officials commenced.[36]: 99–100, 201 [37]: 222–223

The Tomb

29°52′05″N 31°13′10″E / 29.86795°N 31.219416°E

The tomb of Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum was discovered by Egyptologist Ahmed Moussa in the necropolis at Saqqara, Egypt in 1964, during the excavation of the causeway for the pyramid of King Unas.[2]: 98 It is the only tomb in the necropolis where men are displayed embracing and holding hands. In addition, the men's chosen names (both theophorics to the creator-god Khnum) form a linguistic reference to their closeness: Niankhkhnum means "life belongs to Khnum" and Khnumhotep means "Khnum is satisfied;"[39] both names honor the god of pottery, responsible for shaping the human body before its birth, as in the midwife episode of Papyrus Westcar, where King Khufu's children are born. Khnum, active in the Elephantine Island region (the first Nile cataract, near modern Aswan), was also associated with the onset of the annual Nile inundation, especially during the early Dynastic period.[40]: 153–155

The precise king and regnal date of this tomb are unknown; style places it in the latter 5th Dynasty under Nyuserre or Menkauhor. No human remains were discovered inside.[41]: 644 It is believed the tomb was built in stages, first a sequence of two chambers cut into the limestone of a low escarpment in the northern area of Saqqara, then a surface-built mastaba structure added to mate with the earlier construction. This would have occurred as the two intended occupants gained resources.

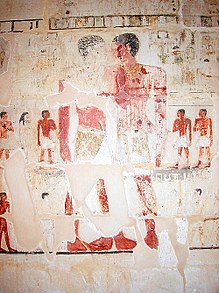

In a banquet scene (treated in a later section), Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep are entertained by dancers, clappers, musicians and singers; in another, they oversee their funeral preparations. In the most striking portrayal, the two embrace, noses touching, in the most intimate pose allowed by canonical Egyptian art, surrounded by what would appear to be their heirs. The superstructure of their tomb

- "was almost completely destroyed because king Unas built his [tomb] causeway over it. It has been reconstructed using the decorated blocks that were found during excavation, and is now open to the public. The part of the tomb that was put into the rock is well preserved. The quality of the painted reliefs is excellent, especially in the first of the rock cut chambers. The various scenes on the western side of the tomb include fishing and fowling in the marshes, stock breeding, papyrus gathering and fights among the boatmen. Opposite are agricultural scenes and scenes of sculptors and jewellers at work."[8]: 88

The Old Kingdom necropolis revolved around the king's pyramid complex[19]: 93–95 and its satellite cemeteries, in which queens, princes, and high officials were interred, queens often in small pyramids of their own, others entombed in underground apartments but memorialized above ground by a substantial building for the deceased's offering chapels and grave goods, the mastaba. This rectangular monument is often 60 feet (18m) or more on its long side and 15 feet (5m) high, and erected directly over the burial site. At Giza, these tombs formed a city of the dead, laid out on a grid of streets and avenues,[42]: 27–29, Figs. 13–17 [31]: 148–151 although later in this article, we see that the necropolis was a bustling center of activity for the living. Layout at Saqqara is similar but less regular. Maps of Saqqara and of Abusir, the home of Nysurre's pyramid, are online at Rice University and at Tour Egypt, a brief overview at the latter.[43][44][20]

During initial development of the necropolis at Saqqara in the 2nd and 3rd Dynasties, the mastaba, a mud-brick and/or limestone superstructure built on the surface over a shaft leading to the actual burial chamber below ground, had an elaborate niched and fluted façade. This is called the palace serekh design.[45] The 4th Dynasty simplified the mastaba so that those of Khufu's reign at Giza, as well as the 5th Dynasty monuments at Saqqara, have smooth sides;[42] Niankhknum and Khnumhotep's beautifully restored structure encased in stone. The exterior has a batter angle like a fortress, the wall sloped back as it rises, except for the topmost course, which forms a vertical cornice.

Unfortunately, the artwork inside did not always fare as well. Some of the blocks were re-used in Unas' causeway and nearly all of them, whether removed from situ or not, suffered moisture and salt damage. Preservation improves in the rock-cut section. Most of the reliefs are legible enough for line drawings to be made of them; allowing their texts and graphical data to come down to us.

Forecourt entrance with architrave and pillars

We progress inward from the tomb entrance as a visitor would. A two-pillared portico makes up the eastern half of the mastaba's façade. The front is inscribed with Niankhkhnum depicted on the left, Khnumhotep on the right. These two reliefs are virtually identical, only the names being different.

Interior of forecourt

This space is fairly small. The west side is decorated with a funerary procession for Niankhkhnum and the east side shows a matching funerary procession for Khnumhotep.

The south wall shows the two men seated before an offering table. Niankhkhnum is seated on the right, while Khnumhotep is seated on the left. The table with offerings stretches out between them. Below the offering scene the two men are depicted netting fowl and fishing. On the left Khnumhotep stands on a papyrus boat. He is accompanied by his wife Khenut and a son and daughter. On the right Niankhkhnum is depicted in a similar manner. He is accompanied by his wife Khentkawes, who was a priestess of Hathor, and a son and daughter as well.[41]

Vestibule

At the entrance scenes of baking bread and brewing beer are depicted. Barley is carefully measured out and turned into bread. Some of the bread is mixed with a date beverage and fermented to produce some type of beer. Other scenes include goat herding, ship building, harvesting scenes, sailing, netting of birds, etc. The east wall contains a legal text. Below this text several people are depicted thought to be the family of the two men. At the very bottom ships are shown. The men are shown standing before the main cabin of the ship.[41]

Court (open to sky)

An undecorated space which serves to connect the vestibule and chambers on the north end of the mastaba with the abutting rock-cut sections of the tomb to their south. Modern security grates now obstruct much of the full sun that would have flooded this small, walled yard, yet little or no sun fell on the vestibule to the outer rock-cut hall described below, as its entrance faces north.[41]

Vestibule

This should not be confused with the previously-mentioned vestibule at the public entrance; here we are arriving from an enclosed court. With names, titles, and standing portraits of the two men, it is much smaller than the other vestibule and without pillars. The lintel's inside surface features another cattle count scene, and each tomb owner appears on one of the side walls with his wife, amid a flow of yet more offerings from the herds.[41]

Outer hall

This outer hall, an antechamber to the final, inner hall, marks the tomb's first, rock-cut phase of construction, and is fully decorated. Before the mastaba was added, it would have been the first room a visitor entered after passing through the forecourt, which was relocated northeast to the far side of the mastaba where it is now. Here, people engage in agricultural occupations including the weighing of corn and grain, the ploughing of fields, and harvesting.

A double doorway to the inner hall is on the west wall, with a broad pillar dividing the doors. Its surface depicts the two men, their children, drawn much smaller to reflect a lesser status, in tow behind each parent.[41] The respective wives do not appear in this scene. Niankhkhnum has three sons and three daughters, Khnumhotep five sons and one daughter, some of whom may be adopted or conceived by a second wife or mistress as they lack the shendyt kilts worn by the others. All the children except Niankhkhnum's youngest son, who still runs naked with his shaved head bearing the single sidelock of youth, are adults despite the scale they are drawn at.[47]: 38 [7]

Inner hall

Entering either of the double doors, we note more registers, of birds and of men leading animals, on the thicknesses of the jambs. Now on the reverse side of the dividing pillar, we see Niankhknum and Khnumhotep embracing again, and a third time on the opposite wall of this small chamber. They are without their children in this innermost sanctuary. Each man has a "false door," a carved, slot-like niche surrounded by inscriptions which was produced in the royal workshops and installed in the tomb. Niankhknum's is seriously damaged.[41] The false door provided an accessway for the deceased, as a spiritual being, to reach offerings left at the tomb by the living. These offerings were to be set on plinths in front of the false doors.[31]: 155–159 [48]: 19, 55 Behind the false doors is a small statue closet known as the serdab. A statue of each man would have been placed here, facing the chamber as if to watch visitors come and go, but invisible to the offering-bringers since the false doors are actually solid. Unfortunately, it appears that tomb robbers removed the statues in antiquity; they are no longer extant.[42]: 31 [7]

Offering formulas in the tomb

According to Taylor, belief that the deceased physically occupies the grave or tomb dates back to predynastic times, when goods including tools and weapons were placed in the grave during the funeral, a practice which inspired the palace serekh design we mentioned above: For high dignitaries, the early dynastic mastaba reflected the palace they had occupied during life; this "tomb-as-residence" idea remained current up through Roman Egypt, although by Nysuerre's day the art program had moved indoors, obviating the need for serrated exterior walls.[31]: 149

Besides its unusual construction with both rock-cut and mastaba sections, this tomb is remarkable for the variety of offering-scene layouts and formulas introduced. Within the 5th Dynasty, it is an example of the invocation Htp dj nswt "an offering the king gives..." to the god, here Anubis, the jackal-headed deity of embalming, in a role that marks royal support for the burial.[32]: 14 [46]: 55, Plate 3, Fig. 4 In all such formulas, the deceased is understood as ultimate beneficiary, as the specified food, drink, raiment, and luxury goods are meant to sustain the ka component of a person's soul in the afterlife. Allen's grammatical analysis of this formula identifies the god (Osiris, Anubis, or Wepwawet) as the agent of the gift via direct genitive connection between the god's name and the combination Htp-dj-nswt, which he takes as a compound word. In his interpretation, the god, acting physically through the king, blesses the deceased.[10]: 366

As seen above, offerings can occur at table, with the tomb owner seated before them, or in the field with workers delivering them to the owner. The latter can be considered tributary due to the owner's status under royal patronage; in temples they may devolve to the local or state gods in question and are usually tendered by the king. In such cases, the terms jnw "that which is brought" and bAkw "works done" come into play. The main point is that they are royal transactions, either diplomatic, when the king receives from foreign emissaries, or redistributive, as when taxes in kind flow to the royal magazines or temples.[50]: 201

Altenmüller discusses another kind of offering, the nDt-Hr "greeting,"[49]: 32–35 extended to a private citizen although undoubtedly as reward for service to the crown. These come from estates (njwwt "towns") the king has granted the deceased, or which the latter has inherited in the line of succession to a grant made in a previous generation.[36]: 166–171 The depictions emphasize agricultural produce—wine, figs, raisins—and desert animals, brought in procession under the watchful eye of a scribe, who holds his inventory sheet at far left in the illustration. Circled in red is a text for viewing the nDt-Hr-offerings:

mAA nDt-Hr jnnt m njwwt.f nbt "See the greetings-offerings which are being brought from all his villages."

The formulas in the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep refer anachronistically to the pr-dSrt "red house," a collections and storage center which had not been active since the 3rd Dynasty. In these greetings offerings, no invocation to the god is made.[49]: 34–35

Banquets and music

The banquet scene (first image)[41]: 643 shows Niankhkhnum clean-shaven (left) and Khnumhotep (wearing a short beard) seated facing one another across comestibles spread between, each with his own breadboard table. Set off by a baseline, this is read separately from the two registers of entertainment below them.[21]: 148–149 A different upper register substitutes in the contemporary Saqqara tomb of Ti (next image), where no food is present with the owner, who is seated holding a scepter, his wife (drawn at half-scale) by his feet. Dining scenes in Egyptian art refer to the afterlife, often in groups seated on the ground as the large dinner tables familiar to us were unknown to Egypt. Ritual purity becomes a matter of special concern in this context: Museums exhibit the ceramic washing bowls, one to pour from and one to catch the dribbling water.[52]: 3–4 Magical utterances and libation precede the meal of the dead; in the soon-forthcoming Pyramid Texts of Unas, we read

"These your cool waters, Osiris—these your cool waters, oh Unis…I have come having gotten Horus’s eye, (Spell 21). Wash yourself, Unis, and part your mouth with Horus’s eye. You shall summon your ka—namely, Osiris—and he shall defend you from every wrath of the dead. Unis, receive to yourself this your bread, which is Horus’s eye (Spell 66)."[54]: 19, 23

Although no 5th Dynasty private tombs call the owner Osiris or mention Horus' eye, Taylor indicates some elements of what became the Pyramid Texts were adapted for non-royal use;[31]: 192–198 particularly the qbH "libation" water[13]: 1332 streaming from a red jar on the slab stela of Nefret-iabet (Louvre 15591, Dyn. 4, reign of Khufu), afront her face so as to suggest its use directly. Ziegler calls this a funeral meal as well as an offering table scene, yet it must have taken place after her death, if at all, given that linen for her mummy is specified on the piece's right half.[53]: 242–244 Numerals "1000" count most of the items pictured, clearly demonstrating the stela's purpose as an offering list. By invocation and magic, if the living were to stop donating to her tomb establishment, then she would still be provided for. The "one thousand in beer, one thousand in bread" phrases[9]: Szene 31 which introduce Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep's offering tables in the rock-cut section of their tomb evoke stelae such as Neferet-iabet's, themselves once affixed to mastaba facades, as found in situ for Wep-em-neferet (possible husband of Nefret-iabet) at Khufu's Giza cemetery.[53]: 245–246

The upper register of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep (corresponding to Ti's) resembles these scenes on slab stelae, without text beyond the two men's names and titles.[9]: Szene 31 Niankhkhnum's wife, seated next to him at the left edge, has been erased; the doubled chair and partially visible label on this side reveals her. She was a rxt nswt "king's acquaintance." Clearly the ensemble of musicians and dancers is formulaic, as this tomb and Ti's bear similar graphic layouts. Nonetheless, a written music program preserves the orders an instructor-maestro (labeled as such by the word sbA behind his head[13]: 1097 ) gives his troupe, accompanied by mmt- and mAt-flutes and sqr m bnt "plucking of the harps:"

Hsjt j.jrj m nw n snwj ntrwj pr r.k jr.s "Singing: Do it thus for the two divine brothers: Begin for them now," the instructor exhorts (hieroglyphs near center right in banquet scene image under the section heading; these are circled in red). About it we hear a mysterious comment:

m.k Trf jTt "Look, the Trf-dance is taken" (lower left corner of image, not circled).[9]: Szene 31

All the men in the second register who aren't playing an instrument are clapping or slapping their thighs except the instructor, standing bent forward at far right. Fourth from left, named Ankhredwi-nesut and playing a flute, is someone who may know the tomb owners, as he is mentioned several times on other walls of this tomb. In the bottom register, another woman, Hemet-Re, possibly Niankhkhnum's daughter and entitled a "keeper of the king's things," stands before six Hst "female singers" at her right. She is backed by seven jbAw "male dancers" with hands upraised. Fourth from left in this register is the person who announces that the dance has been taken, clapping as he does so. In front of him, a pair of men kneel. Each clasps one of the other's hands overhead while pointing his other arm toward the ground.[46]: 142–147, Plate 70, Fig. 25 [9]: 31 Altenmüller has more recently refined the translation to read, "Singing, in this (tomb) as the offering ritual is performed. The (song) of the divine brother. Go up to him." This English wording folds the divine brothers into a song title, reducing their number to just one.[51]: 26

Observing that festive scenes are more concentrated at Saqqara than elsewhere during the 5th Dynasty, Altenmüller goes on to compare several scenes from this genre, placing them in the context of a family and the gods it associates with, which becomes a heritable scheme along with the titles. At Saqqara, many reliefs involve sniffing the lotus blossom, an activity we saw Khentikawes engage in during her husband's bird hunt.[51]: 17, 25 Returning our gaze to the top register above the music, we see that Khnumhotep is holding a lotus blossom in his lap with his left hand. If he is watching the dancers, they are in front of him, not in a basement below. Egyptian perspective encompasses both space and time on the two-dimensional relief; heads, arms, and legs in profile but torso frontal. What is above may really lie behind; what is behind may be "pluralized" with multiple outlines as animals often are, while left and right sometimes represent consecutive action as discussed later. Statues of course look forward as expected.[55]: 9–10 [48]: 19, 55 [21]: 148–149 Complexities encountered in music and dance remain poorly understood today, although Allen thinks that literature was written in meter as well.[11]: 2–3

On the adjoining east wall, near another seated portrait of Khnumhotep,[46]: Plate 62 a carpenter makes a furniture item probably used at banquets: a portable wooden recliner or backrest,[57]: 151 an angled plate set on the ground or on a bench to lean against, so that one is lying down with upper body propped up. To the right, closer to Niankhnum and the banquet scene, are jewelers at work.[46]: Plate 64 Banqueting could take place in the "presence" of the king even if persons of differing rank did not eat together: A relief from Sahure's causeway shows (in part) a feast craftsmen and their overseers enjoy at the king's behest, divine presence signified by the lion emerging beside a papyrus umbel;[52]: 27 the goddesses Bastet and Sekhmet are associated with royal sustenance at the mortuary complex. In the tomb of Iny (late Dynasty 6), a boastful text explains this:

"I was seated eating bread in the (royal) daily round, and great was His Person's (Hm.f, the king) satisfaction at seeing me eat, more [so] than [for] any peer of mine."[52]: 5

This sentence, written a bit later historically, carries an autobiographical tone, blurring the distinction between life and hereafter, although we assume real-life, non-funerary meals must have been served at court. The tomb is largely a continuation of normal everyday life, the thing the dead wanted most: they were not excluded from the society of the living.[31]: 41 At 5th Dynasty Saqqara, the deceased Rashepses can contemplate a sculptor reaching for a tray of fruit, even if with fewer words.[52]: 5 Officials, who sometimes were women, presided over musical festivities: In a 4th Dynasty mastaba at Giza, the owner Ity and his wife both bore the rx nswt "king's acquaintance" title:

rx nswt jmj-r Hxt pr aA jtj rx nswt Hmt.f mrt.f wsrt-kA "Acquaintance of the king, master of the king's music Acquaintance of the king, his wife, his beloved Wasretka."[58]: 59

Conventions treating a limited number of themes made up the Old Kingdom art corpus; rules meant to relate what is shown on the wall with what happens in an ideal life, so that the dead can continue to have access to it. First designed for royalty, it is extended to private citizens, minus the king's privileged contacts with deity. Figures face the tomb entrance where possible, looking out toward the world of the living.[21]: 22, 148–149 [48]: 72–74 Lower registers tend to comprise foregrounds, denoting a venue closer to the reader than the top registers do. Seriation of episodes is read horizontally within a register, the people and objects assembled in groups distinguished by what they are doing or by the direction they face. Choice of sunk versus raised relief conveys meaning; the latter used in the intimate rear areas of tombs, the former at the entrance.[21]: 22 Niankhnum and Khnumhotep's tomb uses sunk relief at the entrance to its rock-cut section, which had faced the public before the owners added the mastaba. The two officials could emulate King Khafre's 4th Dynasty practice of gouging a titulary into pillars, but only in limestone, not the hard granodiorite Khafre used.[59]: 44–45, 48 [21]: 98–100 The banquet scene exemplifies an Egyptian desire to impose structure on life and death, yet in an exuberant manner, its figures imbued with color.

Career

Since personal information modern reviewers desire is usually unavailable, a situation true for Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, routines of daily life must be pieced together from archaeological inference or read between lines of surviving texts, all of which (including the accounting data) express elite viewpoints. Kemp discusses methods for obtaining knowledge under such constraints, pointing out that local religion came with a varnish distinct from that of the state cults.[36]: 112–113, 134 Art cannot be totally divorced from reality; the agricultural year and cattle counts seen on walls happened. Yet text orbits near myth. So the cattle count is as much ritual as systematic tax collection, and so a lion goddess, addressing King Nyuserre as "my son," gives him milk from her teat at his valley temple.[17]: 277 [60]: 236 [61]: 352

Relatively few Egyptians could read and write, skill among the literate distributed unevenly as well after schooling based upon individual tutelage—its ad hoc nature evidenced by mistranscription of hieratic source material by draftsmen (zXAw-qdwt "outline scribes") arranging formal inscriptions on walls and statues.[10]: 467 [28]: 577, 583–584 Living conditions could turn harsh, even for middle classes: In a somewhat later, 12th Dynasty social context, the prosperous tenant farmer Heqanakht orders cutbacks for his household, citing that year's suboptimal Nile flood and hunger in the land. Insects ate a substantial fraction of stored grain supplies at New Kingdom Amarna, a condition we have little reason to imagine spared 5th Dynasty communities near Memphis.[62]: 16–17 [63]: 318

Bureaucrats

A solar temple separate from the pyramid complex was a feature unique to the seven 5th-Dynasty kings from Userkaf to Menkauhor, of which two have been excavated in modern times. Nyuserre's was richly decorated with reliefs, today in a fragmentary condition. These temples centered on worship of the bn-bn "Benben" stone, an inherited cultural artifact associated with the Heron of Plenty who later graced vignettes in the Book of the Dead.[36]: 137–141, fig. 48 [64]: 73, Plates 7, 27 [65][Notes 6] We do not know where Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep spent most of their day; the palace, the solar or the pyramid temple, or their own residential compounds all possibilities. The solar temple was used, however, for the king's hb-sd "Heb-sed," the festival celebrating his 30th anniversary on the throne. Nyuserre's reliefs depict, as had Djoser's back in the 3rd Dynasty, the king watching tributary files pass in review and demonstrating his physical fitness in a game where he ran to and fro between two posts on a marshaling ground. [36]: 104–107 [21]: 123 While at least part of the king's funeral was held at the pyramid complex, his other major monument, the pyramid was never a one-shot affair to be left unattended after services, as graves of modern heads of state are. Accounting papyri at Abusir detail a persistent mortuary cult's receipt of goods over decades.[19]: 94 [66]: 350–351

The vizier, highest official beneath the king, handled Old Kingdom administration. Absent indexed state archives, business transactions proceeded face-to-face, or sometimes by letter while participants kept copies of any legal documents generated. Each proof might be in duplicate, one for consultation, the other sealed to frustrate tampering—by Ramesside times both ingeniously accommodated on the same papyrus roll, where the seal blocked only half its length. In other words, there were bureaus and scribes but no constitutional underpinnings behind them: Whoever held greatest personal influence at a given moment took the decisions and implemented these through his own patronage as best he could, an arrangement not noted for efficiency, yet remarkably effective in seeing a king's monuments through to completion.[17]: 64–65, 259, 342–343 [36]: 179–180, 201–203

On duty at the sun temple, Niankhkhnum or Khnumhotep may have watched over subordinate officials, such as the m-r pr Sna "overseer of the magazines" who in turn supervised crews of porters stocking and withdrawing material from the granaries and store-rooms. This suggests either that the m-r ranks below the Hm-nTr priest, at least within the temple enclosure, or that the appellations we've discussed, m-r, sHD, Hm-nTr, and wab, aren't reliable status indicators. Barta reports Helck's assertion that the pr Sna was a group of workshops, in which case processed goods were being made in the temple precinct. The Abusir papyri, a set of accounting spreadsheets, relates the pr Sna to the pyramid temple, where Niankhkhnum was "only" a wab, adding to the confusion temple bureaucracy presents to scholars. [12]: 61 It is clear no legal separation of temple from palace existed; Old Kingdom temples were named after the king, in contrast to later temples such as Karnak dedicated to gods (to whom the king nonetheless donated). That theft could be a problem is seen in New Kingdom legal disputes; presumably the senior officials were expected to monitor it. [16]: 21 A police captain is named and illustrated among the genuflectors in the funeral procession at the mastaba.[9]: Szene 12

Manicurists, hairdressers, and adorners

Care of the king's body and wardrobe in preparation for his public appearances required a large number of aides, apparently working in different ateliers each under its own leadership. In addition to the manicurists whom Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep supervised (discussed in the titulary section of this article), the palace had attendants under one or more men holding the title jrj nfr HAt "keeper of the headdress," responsible for the king's wigs and headcloths, jrw Snj " hairdressers,[13]: 189 who kept him shaven, and an m-r n jzwj Xkrwt nswt "overseer of the two chambers of king's adorners."[12]: 74 The post of Xkrt nswt "adorner of the king" was always held by women, who were legally, if not socially, equal to men in Egypt.[16]: 8 Neferhotep-Hathor is labeled with this status at the funeral procession of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep.[9]: Szene 12

How, or how often, personnel in the hairdressers' shop, which from titulary evidence stands higher than the manicurists in 5th and 6th Dynasty prestige rankings, communicated with the latter remains unknown. No hairdressers are labeled at the funeral procession. Ptahshepses, the titular keeper of the headdress who became Nyussere's vizier, [12]: 73 and Ty, overseer of the pyramids and sun temples are two officials whom Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep or their children may have worked with. They were buried at Abusir and Saqqara, respectively. Ty's large mastaba and extra titles suggest attainment of higher rank.[41]: 468–478 A door jamb in Ptahshepses' even grander mastaba, besides TAtj "vizier," displays the simple title HAt-a "one whose arm is in front," a pure honorific Allen distinguishes from the m-r and jrj titles specifying responsibility domains we've encountered up to now. We must also observe that his jrj nfr HAt "keeper of the headdress" epithet, recorded in many locations of the tomb, is spelled with the mouth sign (Gardiner D21), not the eye sign (D4), so that it shares the introductory word of jrj-pat "hereditary prince," another of Allen's honorifics.[67]: 34 [13]: 178 [10]: 34 This fact traverses some distance in explaining the apparently higher standing of the hairdressers' shop. Such arcane hierarchy isn't foreign to our own day, where the president of the United States commands TV makeup artists and speechwriters all having different effective ranks within the White House staff.

Notes

- ^ After registration, must search for pages on Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae: Click picture on home page to enter site. Pick "navigating the hierarchical tree of objects and texts" on the database search page. Position of texts in the hierarchical tree is *Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae, *Strukturen und Transformationen Berlin-Brandenburgische, *Grabinschriften des Alten Reiches, *Sakkara, *Unas-Friedhof, *Mastaba des Nianch-Chnum und Chnum-hotep. Be sure to click on the nodes themselves, at left on each line.

- ^ Wall texts in Thes. Ling. Aeg. identified by Porter & Moss : Szenen 1.2 and 1.3 [Porter & Moss III, p. 641, I 1(c-d)]; Szene 12 [Porter & Moss III, p. 642, II 8]; Szene 13 [Porter & Moss III, p. 642, II 9]; Szene 15 [Porter & Moss III, p. 642, II 9]; Szene 23 [Porter & Moss III, p. 643, IV 15]; Szene 31 [Porter & Moss III, p. 643, V 20].

- ^ To avoid display problems, the MDC system is used here to transliterate Egyptian words, hence note that A and a are different. The complete set of consonantal “letters” (in lexical order for consulting an Egyptian dictionary) are A, j, y, a, w, b, p, f, m, n, r, h, H, x, X, z, s, S, q, k, g, t, T, d, D, set apart in italics. Other systems exist with special fonts; the A looks like 3 and the a like ‘ in books using these. (Wikipedia list here). Be warned Egyptian scribes did not use hieroglyphs in the same way we use letters. (Primer on language here).

- ^ The titulary in this article elects Egyptian sHD = Aufseher = "inspector," jmAx = Ehrwürdigkeit = "honored," nb = Herr = "lord," jr or jrj = Verwalter = "doer, maker, keeper, or supervisor," Hr or Hrj = Hüter = "guardian," m-r or jmj-r = Vorsteher = "overseer." This runs contra German-speaking Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae; yet English-language books almost always call the m-r an "overseer," and, less consistently, call the sHD an "inspector." Literally, jmj-r means "one whom the mouth is in," that is, a word-giver, while sHD is a causative verb meaning "to make bright." (Allen, 2010, pp. 93, 469)

- ^ See also maps on pp. 22-23. There was a harbor and port for docking the ships of state at the entrance to the valley temple, which they accessed from the Nile by going up a canal. The valley temple was a few yards (meters) beyond the line where arable land wetted by the annual Nile flood stops abruptly. A causeway, roofed so that dignitaries (especially women) need not face the brutal sun, led uphill to the pyramid and its temples. Women are rendered in yellow pigments instead of red ochre because they spent less time outdoors.

- ^ In BOD Spell 83, jwnw "Iunu" is Heliopolis, now reduced to a Middle Kingdom obelisk of Senwosret I and some foundation walls in a Cairo city park but long the center of solar theology and its priests.

References

- ^ On the Old Kingdom sound correspondences of Egyptological transcription symbols cf. Frank Kammerzell, Old Egyptian and Pre-Old Egyptian: Tracing Linguistic Diversity in Archaic Egypt and the Creation of the Egyptian Language, in: Texte und Denkmäler des ägyptischen Alten Reiches, ed. by Stephan J. Seidlmayer, Thesaurus Lingua Aegyptiae 3, Achet 2001, p. 230. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Rice, Michael (2002). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt?. Abingdon, UK: Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415154499.

- ^ Dowson, Thomas (2007). "Archaeologists, Feminists, and Queers: Sexual Politics in the Construction of the Past". In Geller, Pamela; Stockett, Miranda (eds.). Feminist Anthropology: Past, Present, and Future. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 96ff. ISBN 978-0-81-222005-6.

- ^ McCoy, John (Dallas Morning News) (20 July 1998). "Evidence of Gay Relationships exists as early as 2400BC". Egyptology.com. Greg Reeder. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Mwah ... is this the first recorded gay kiss? by W. Holland in the Sunday Times, January 1, 2006

- ^ Stern Keith Queers in History Dallas, Texas: 2009 BenBella Books

- ^ a b c d The mastaba of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep by J. Hirst on Osirisnet.net

- ^ a b Lorna Oakes, Pyramids Temples and Tombs of Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Atlas of the Land of the Pharaohs, Hermes House:Anness Publishing Ltd, 2003. p.88

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences. "Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae". Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae. Registration (free) required for access; see notes. In German, with limited English translation. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Allen, James (2010). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-74144-6.

- ^ a b c Allen, James (2015). Middle Egyptian Literature. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 2–3, 59. ISBN 978-1-107-45607-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Barta, Miroslav (2001). Abusir V: The Cemeteries at Abusir South I. Prague: Czech Inst. of Egyptology. ISBN 80-86277-18-6. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hannig, Ranier (2003). Ägyptisches Wörterbuch I. Mainz, Germany: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-3088-X.

- ^ Museum of Fine Arts Boston, museum record: gold cylinder seal, reign of Djedkare Isesi, Dyn. 5. Accession No. 68.115. "Seal of Office". Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Author. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Baud, Michel (2005). "The Birth of Biography in Ancient Egypt: Text Format and Content in the 4th Dynasty". In Seidlmayor, Stephan (ed.). Texte und Denkmäler des ägyptischen Alten Reiches. Berlin: Achet (Thesaurus Linguae Aegypiae, Band 3). ISBN 3-933684-20-X.

- ^ a b c Teeter, Emily (2011). Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61300-2.

- ^ a b c d Eyre, Christopher (2013). The Use of Documents in Pharaonic Egypt. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967389-6.

- ^ a b Fischer, Henry George (1996). Varia Nova III (PDF). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87-099755-6. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Arnold, Dorothea (1999). "Royal Reliefs". In Fuerstein, Carol (ed.). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (exhibition catalog). pp. 93–95, see also illustrations on pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-87099-906-0.

- ^ a b c Dunn, Jimmy. "The Sun Temple of Niuserre at Abu Ghurab". Tour Egypt. Government of Egypt. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ćwiek, Andrzej (2003). Relief Decoration on the Royal Funerary Complexes of the Old Kingdom (PDF). Poland: University of Warsaw (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Fodor's (2011). Fodor's Egypt. (Volume 4) New York: Fodor's Travel Publications. ISBN 978-1-40-000519-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Dunn, Jimmy. "Egypt: The Pyramid Complex of Niuserre at Abusir". Tour Egypt. Government of Egypt. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Bard, Kathryn (2007). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-1149-2.

- ^ Dorman, Peter (2005). "The Proscription of Hatshepsut". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (exhibition catalog). ISBN 1-58839-172-8. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ a b Bareš, Ladislav (2000). "The Destruction of the Monuments at the Necropolis of Abusir". In Barta, Miroslav; Krejči, Jaromir (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Czech Academy of Sciences. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- ^ Verner, Miroslav (2002). Abusir: Realm of Osiris. New York: American Univ. in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9-77-424723-1.

- ^ a b Baines, John (1983). "Literacy and Ancient Egyptian Society". Man. 18 (3). doi:10.2307/2801598. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Garcia, Moreno (2012). "Deir el-Gabrawi". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology: 1. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ a b Malek, Jaromir (2000). "The Old Kingdom". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Taylor, John (2001). Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. pp. 42–43, 192–198. ISBN 0-226-79164-5.

- ^ a b Allen, James (2006). "Some aspects of the non-royal afterlife in the Old Kingdom". The Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology: Proceedings of the Conference Held in Prague, May 31 – June 4, 2004 (PDF). Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology. ISBN 80-200-1465-9. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ University of Pennsylvania. "Saqqara Expedition". Penn Museum. Author. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ Friends of Saqqara Foundation. "The Anglo-Dutch mission 1975-1998". Saqqara.nl. Author. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Ravens, Maarten (2000). "Twenty-five Years of Work in the New Kingdom Necropolis of Saqqara". In Barta, Miroslav; Krejči, Jaromir (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Czech Academy of Sciences. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Kemp, Barry (2006). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23550-1.

- ^ Regulski, Ilona (2009). "Investigating a new Dynasty 2 necropolis at South Saqqara" (PDF). British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan. 13 (2009). Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Newberry, Percy (1893). Griffith, Francis L. (ed.). Beni Hasan Part II (University of Heidelberg scanned copy for ed.). London: Egypt Exploration Society. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Dunn, Jimmy. "The Tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep at Saqqara in Egypt". Tour Egypt. Government of Egypt. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide... (pbk. ed.). New York: Oxford. pp. 153–155. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Porter & Moss (1981). Malek, Jaromir (ed.). Topographical Biography III: Memphis, Part 2: Saqqara to Dahshur (PDF) (revised ed.). Oxford: Griffith Institute. pp. 641–644, Plan LXVI. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Janosi, Peter. "The Tombs of Officials" (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (exhibition catalog). Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Anonymous (19th century map). "Pyramids and Tombs of Sakkara [and] Group of Pyramids of Sakkara [and] Pyramids and Tombs of Abusir". Travelers of the Middle East. Rice University. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Dunn, Jimmy. "An Overview of Saqqara Proper in Egypt". Tour Egypt. Government of Egypt. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Egypt Exploration Society. "Saqqara and Memphis". Egypt Exploration Society. Author. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Moussa, Ahmed & Altenmüller, Hartwig (1977). Das Grab des Nianchchnum und Chnumhotep (in German). Darmstadt, Germany: Philipp von Zabern.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilkinson, Richard (1994). Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art (pbk. ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28070-3.

- ^ a b c Robins, Gay (2008). The Art of Ancient Egypt. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 19, 55. ISBN 978-0-67-403065-7.

- ^ a b c Altenmüller, Hartwig, "Presenting the nDt-Hr-offerings to the tomb owner" (2006). Barta, Miroslav (ed.). The Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology (PDF). Prague, Czech Rep.: Czech Institute of Egyptology. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gordon, Andrew (1998). "Review of 'The Official Gift in Ancient Egypt,' by Edward Bleiberg". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 35 (1998): 201–203. doi:10.2307/40000473. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Altenmüller, Hartwig (2008). "Vater, Brüder und Götter: Bemerkungen zur Szene der Übergabe der Lotosblüte". In Spiekermann, Antje (ed.). Festschrift Bettina Schmitz (PDF) (in German). Hildesheim, Germany: Hildesheim Museum, Verlag Gebrüder Gerstenberg. pp. 17, 25–26, Fig. 4. ISBN 978-3-8067-8725-2. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Singen, während in diesem (Grab) das Opferritual durchgeführt wird, des (Lieds) vom göttlichen Bruder. Steige du auf zu ihm.

- ^ a b c d e Baines, John (2014). "Not only with the dead: banqueting in ancient Egypt". In Ghitta, Ovidu (ed.). Historia 59 (PDF). Cluj-Napoca, Romania: Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai. pp. 4, Fig. 4. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ a b c Ziegler, Christiane (1999). "Slab Stela of Nefret-Iabet (Cat. No. 51), Slab stela of Wep-em-Nefret (Cat. No. 52)". In Fuerstein, Carol (ed.). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 242–244. ISBN 0-87099-906-0. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Allen, James (2005). The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-182-7.

- ^ Hagen, Rose-Marie & Ranier (2007). Wolf, Norbert (ed.). Egypt Art. Los Angeles: Taschen. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-3-8228-5458-7.

- ^ Borchardt, Ludwig (1913). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Sahure 2 (in German). Leipzig: Hinrich. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Brovarski, Edward (1996). "An Inventory List from Covington's Tomb". In Der Manuelian, Peter (ed.). Studies in Honor of William Kelly Simpson. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. ISBN 0-87846-390-9.

- ^ Weeks, Kent (1994). Giza Mastabas V: Mastabas of Cemetery g 6000. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. p. 59. ISBN 0-87846-322-4.

- ^ Chauvet, Violane (2008). "Decoration and Architecture: The Definition of Private Tomb Environment". In D'Auria, Sue (ed.). Servant of Mut: Studies in Honor of Richard A. Fazzini. Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15857-3.

- ^ Warden, Leslie (2013). Pottery and Economy in Ancient Egypt. Boston: Brill. p. 236. ISBN 978-9-00-425-985-0.

- ^ Arnold, Dorothea (1999). "Lion-Headed Goddess Suckling King Niuserre (Cat. No. 118)". In Fuerstein, Carol (ed.). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (exhibition catalog). pp. 352–353. ISBN 0-87099-906-0.

- ^ Allen, James (2002). The Heqanakht Papyri. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 1-58839-070-5. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia; Shortland, Andrew; Rowland, Joanne (2015). Science in the Study of Ancient Egypt. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31-739195-1.

- ^ Von Dassow, Eva (1997). The Egyptian Book of the Dead. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6489-3.

- ^ University College London. "Book of the Dead Chapter 83". Digital Egypt for Universities. Author. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ Ziegler, Christiane (1999). "Document from the Royal Records of Abusir (Cat. No. 117)". In Fuerstein, Carol (ed.). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 350–351. ISBN 0-87099-906-0. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Verner, Miroslav (1986). Abusir I: The Mastaba of Ptahshepses. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Baines1985" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Booth2015" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "Jones1995" is not used in the content (see the help page).

Literature

- Thomas A. Dowson, "Archaeologists, Feminists, and Queers: sexual politics in the construction of the past". In, Pamela L. Geller, Miranda K. Stockett, Feminist Anthropology: Past, Present, and Future, pp 89–102. University of Pennsylvania Press 2006, ISBN 0-8122-3940-7

- A. M. Moussa and H. Altenmüller, Das Grab des Nianchchnum und Chnumhotep, Mainz 1977

External links

- The mastaba of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep by J. Hirst on Osirisnet.net

- Gallery and background, egyptology.com

- References and bibliography, egyptology.com

- "Mwah ... is this the first recorded gay kiss?" The Sunday Times, January 1, 2006

- "Evidence of gay relationships exists as early as 2400 B.C." The Dallas Morning News, July 20, 1998

- "Same-Sex Desire, Conjugal Constructs, and the Tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep," Greg Reeder, World Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 2, Queer Archaeologies (October, 2000), pp. 193–208