Madam C. J. Walker: Difference between revisions

As I explained in my memoir, Colored People, “So many black people still get their hair straightened that it’s a wonder we don’t have a national holiday for Madame C.J. Walker, |

Boomer Vial (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 2601:14B:4401:17AE:3DD5:C1E9:743A:3C08 (talk) to last version by ClueBot NG |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox person |

|||

As I explained in my memoir, Colored People, “So many black people still get their hair straightened that it’s a wonder we don’t have a national holiday for Madame C.J. Walker, who invented the process for straightening kinky hair, rather than for Dr. King.” I was joking, of course, but mostly about the holiday; the history and politics of African-American hair have been as charged as any “do” in our culture, and somewhere in the story, Madam C.J. Walker usually makes an appearance. |

|||

| name = Madam C. J. Walker |

|||

| birth_name = Sarah Breedlove |

|||

| image = Madam CJ Walker face circa 1914.jpg |

|||

| caption = Walker in 1903 |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1867|12|23|mf=y}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Delta, Louisiana]], United States |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|1919|5|25|1867|12|23|mf=y}} |

|||

| death_place = {{Nowrap|[[Irvington-on-Hudson, New York]], United States}} |

|||

| resting_place =[[Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York)]] |

|||

| resting_place_coordinates = <!-- {{Coord|LAT|LONG|type:landmark|display=inline}} --> |

|||

| monuments = |

|||

| residence=[[Villa Lewaro]], Irvington-on-Hudson, New York |

|||

| nationality = American |

|||

| other_names = |

|||

| education = |

|||

| occupation= [[businessperson|Businesswoman]], [[hair care|hair-care]] entrepreneur,<br/>[[Philanthropy|Philanthropist]], and<br />[[Activism|Activist]] |

|||

| known_for = |

|||

| home_town = |

|||

| net_worth = <!-- Net worth should be supported with a citation from a reliable source --> |

|||

| height = <!-- {{height|m=}} --> |

|||

| weight = <!-- {{convert|weight in kg|kg|lb}} --> |

|||

| party = |

|||

| boards = |

|||

| religion = <!-- Religion should be supported with a citation from a reliable source --> |

|||

| spouse=Moses McWilliams (married 1882–1887)<br/>John Davis (married 1894 – c. 1903)<br/>Charles Joseph Walker (married 1906–1912) |

|||

| children = [[A'Lelia Walker]] |

|||

| relatives = |

|||

| awards = |

|||

| signature = |

|||

| signature_alt = |

|||

| signature_size = |

|||

| website ={{URL|www.madamcjwalker.com}} |

|||

| footnotes = |

|||

}} |

|||

[[File:MadameCJWalkerdrivingautomoblie.png|thumb|right|Madam Walker and several friends in her automobile]] |

|||

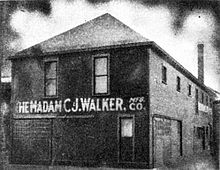

[[File:Madam CJ Walker Manufacturing Company, Indianapolis, Indiana (1911).jpg|thumb|right|C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, Indianapolis, 1911]] |

|||

'''Sarah Breedlove''' (December 23, 1867 – May 25, 1919), known as '''Madam C. J. Walker''', was an African American [[entrepreneur]], [[philanthropist]], and a political and social [[Activism|activist]]. Eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America,<ref name="Philanthropy"/> she became one of the wealthiest African American women in the country, "the world's most successful female entrepreneur of her time," and one of the most successful [[African-American businesses|African-American business]] owners ever.<ref>{{cite triumph|page=75}}</ref> |

|||

Madam C.J. Walker |

|||

Madam C.J. Walker. Photo courtesy A’Lelia Bundles/Madam Walker Family Collection. |

|||

Walker made her fortune by developing and marketing a line of beauty and hair products for black women through [[Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company]], the successful business she founded. Walker was also known for her philanthropy and activism. She made financial donations to numerous organizations and became a patron of the arts. [[Villa Lewaro]], Walker’s lavish estate in [[Irvington-on-Hudson, New York]], served as a social gathering place for the African American community. |

|||

Most people who’ve heard of her will tell you one or two things: She was the first black millionairess, and she invented the world’s first hair-straightening formula and/or the hot comb. Only one is factual, sort of, but the amazing story behind it and how Madam Walker used that accomplishment to help others as a job creator and philanthropist might be jarring — and surprisingly empowering — even to the skeptics. I know it was for me in revisiting her life for this column. |

|||

==Early life== |

|||

Thanks to the work of numerous historians, among them Madam Walker’s prolific great-granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, as well as Nancy Koehn and my colleagues at Harvard Business School, I no longer see one straight line from “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower” to current menus of extensions, braids and weaves; nor do I see a single line connecting this brilliant, determined person — who struggled doggedly for a life out of poverty, and for black beauty, pride and her own legitimacy (in the face of black male resistance) as a black business woman during the worst of the Jim Crow era — to the most successful black women on the stage today. |

|||

Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, near [[Delta, Louisiana]], to Owen and Minerva (Anderson) Breedlove.<ref name=BWA1209>Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in ''Black Women in America'', v. II, p. 1209.</ref><ref name=Bundles-website>{{cite web|last1=Bundles|first1=A’Lelia|title=Madam C.J. Walker |url = http://www.madamcjwalker.com/bios/madam-c-j-walker/ |website=Madame C.J. Walker|accessdate=25 February 2015}}</ref> Sarah was one of six children, which included an older sister, Louvenia, and four brothers: Alexander, James, Solomon, and Owen Jr. Breedlove's parents and her older siblings were enslaved on Robert W. Burney's Madison Parish plantation, but Sarah was the first child in her family born into freedom after the [[Emancipation Proclamation]] was signed. Her mother died, possibly from [[cholera]], in 1872; her father remarried, but he died within a few years.{{citation needed|date=February 2016}} Orphaned at the age of seven, Sarah moved to [[Vicksburg, Mississippi]], at the age of ten and worked as a domestic. Prior to her first marriage, she lived with her older sister, Louvenia, and brother-in-law, Jesse Powell.<ref name=BWA1209/><ref name=indiana-history>{{cite web|title=Madam C. J. Walker |url = http://www.indianahistory.org/our-collections/reference/notable-hoosiers/madam-c.j.-walker#.VPIQUlPF_0p |publisher=[[Indiana Historical Society]]|accessdate=2015-02-28 }}</ref> |

|||

==Marriage and family== |

|||

“Up From” Sarah Breedlove |

|||

In 1882, at the age of fourteen, Sarah married Moses McWilliams, possibly to escape mistreatment from her brother-in-law.<ref name=BWA1209/> Sarah and Moses had one daughter, [[A'Lelia Walker|Lelia McWilliams]], born on June 6, 1885. When Moses died in 1887, Sarah was twenty; Lelia was two years old.<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=NC100Bio>{{cite web | author=A'lelia Bundles| title =Biography of Madam C. J. Walker | work = | publisher =National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Inc., Oakland/Bay Area Chapter | date =2014 |url= http://www.onehundredblackwomen.com/madame-c-j-walker/ | format = | accessdate =2016-02-05}}</ref> Sarah remarried in 1894, but left her second husband, John Davis, around 1903 and moved to [[Denver]], [[Colorado]], in 1905.<ref name=GS360>{{cite book | author= Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, eds. | title = Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State | publisher =Indiana Historical Society Press| year =2015 | location =Indianapolis | page =360 | url = | isbn =978-0-87195-387-2}}</ref><ref name="PhilanthropyX">{{cite web|title=The Philanthropy Hall of Fame: Madam C. J. Walker |url= |

|||

On December 23, 1867, Sarah Breedlove was born to two former slaves on a plantation in Delta, La., just a few months after the second Juneteenth was celebrated one state over in Texas. While the rest of her siblings had been born on the other side of emancipation, Sarah was free. But by 7, she was an orphan toiling in those same cotton fields. To escape her abusive brother-in-law’s household, Sarah married at 14, and together she and Moses McWilliams had one daughter, Lelia (later “A’Lelia Walker”), before Moses mysteriously died. |

|||

http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/hall_of_fame/madam_c._j._walker |publisher=Philanthropy Roundtable|accessdate=2015-03-01}}</ref> |

|||

In January 1906, Sarah married Charles Joseph Walker, a newspaper advertising salesman she had known in [[Missouri]]. Through this marriage, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker. The couple divorced in 1912; Charles died in 1926. Lelia McWilliams adopted her stepfather's surname and became known as [[A'Lelia Walker]].<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=BWA1210-11>Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in ''Black Women in America'', v. II, pp. 1210–11.</ref><ref name=Riquier>{{cite web| author =Andrea Riquier | title =Madam Walker Went from Laundress to Success | publisher=Investor's Business Daily | date =2015-02-24| url = http://news.investors.com/management-leaders-and-success/022415-740635-madam-walker-built-hair-care-empire-rose-from-washerwoman.htm|accessdate =2016-02-08}}</ref> |

|||

Now that Reconstruction, too, was dead in the South, Sarah moved north to St. Louis, where a few of her brothers had taken up as barbers, themselves having left the Delta as “exodusters” some years before. Living on $1.50 a day as a laundress and cook, Sarah struggled to send Lelia to school — and did — while joining the A.M.E. church, where she networked with other city dwellers, including those in the fledgling National Association of Colored Women. |

|||

==Career== |

|||

In 1894, Sarah tried marrying again, but her second husband, John Davis, was less than reliable, and he was unfaithful. At 35, her life remained anything but certain. “I was at my tubs one morning with a heavy wash before me,” she later told the New York Times. “As I bent over the washboard and looked at my arms buried in soapsuds, I said to myself: ‘What are you going to do when you grow old and your back gets stiff? Who is going to take care of your little girl?’ ” |

|||

In 1888 Sarah and her daughter moved to [[St. Louis|Saint Louis]], Missouri, where three of her brothers lived. Sarah found work as a laundress, barely earning more than a dollar a day, but she was determined to make enough money to provide her daughter with a formal education.<ref name=bundles /><ref>{{Cite web|url = http://www.biography.com/people/madam-cj-walker-9522174#early-entrepreneurship|title = Madam C.J. Walker Biography|date = |accessdate =2016-02-15 |website =Biography.com |publisher = A&E Television Networks|author= Editors}}</ref> During the 1880s, Breedlove lived in a community where [[Ragtime|ragtime music]] was developed—she sang at the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and started to yearn for an educated life as she watched the community of women at her church.<ref name="Philanthropy" /> As was common among black women of her era, Sarah experienced severe dandruff and other scalp ailments, including baldness, due to skin disorders and the application of harsh products such as [[lye]] that were included in soaps to cleanse hair and wash clothes. Other contributing factors to her hair loss included poor diet, illnesses, and infrequent bathing and hair washing during a time when most Americans lacked indoor plumbing, central heating and electricity.<ref name=Riquier/><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001">{{cite book | author=A'Lelia Bundles| title=On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker| publisher=Scribner |location=New York |

|||

|year=2001| pages = | url = | isbn =0-7434-3172-3}}</ref><ref name=ingham>{{cite web | author=John N. Ingham|title =Madame C. J. Walker |publisher=American National Biography Online| date=February 2000 |url = | accessdate=}} (subscription required)</ref> |

|||

[[File:The Childrens Museum of Indianapolis - Madame C.J. Walkers Wonderful Hair Grower.jpg|thumb|right|alt=A container of Madame C.J. Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower is held in the permanent collection of [[The Children's Museum of Indianapolis]].|Madame C.J. Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower in the permanent collection of [[The Children's Museum of Indianapolis]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Madam C.J. Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower product container|url=http://digitallibrary.imcpl.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tcm/id/168|publisher=The Indianapolis Public Library|accessdate=2 March 2015}}</ref>]] |

|||

Adding to Sarah’s woes was the fact that she was losing her hair. As her great-granddaughter A’Lelia Bundles explains in an essay she posted on America.gov’s Archive: “During the early 1900s, when most Americans lacked indoor plumbing and electricity, bathing was a luxury. As a result, Sarah and many other women were going bald because they washed their hair so infrequently, leaving it vulnerable to environmental hazards such as pollution, bacteria and lice.” |

|||

Initially, Sarah learned about hair care from her brothers, who were barbers in Saint Louis.<ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> Around the time of the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition]] (World's Fair at St. Louis in 1904), she became a commission agent selling products for [[Annie Malone|Annie Turnbo Malone]], an African American hair-care entrepreneur and owner of the Poro Company.<ref name=BWA1209/> While working for Malone, who would later become Walker’s largest rival in the hair-care industry,<ref name="Philanthropy" /> Sarah began to adapt her knowledge of hair and hair products to develop her own product line.<ref name=BWA1210-11/> |

|||

In the lead-up to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Sarah’s personal and professional fortune began to turn when she discovered the “The Great Wonderful Hair Grower” of Annie Turnbo(later Malone), an Illinois native with a background in chemistry who’d relocated her hair-straightening business to St. Louis. It more than worked, and within a year Sarah went from using Turnbo’s products to selling them as a local agent. Perhaps not coincidentally, around the same time, she began dating Charles Joseph (“C.J.”) Walker, a savvy salesman for the St. Louis Clarion. |

|||

In July 1905, when she was thirty-seven years old, Sarah and her daughter moved to [[Denver]], [[Colorado]], where she continued to sell products for Malone and develop her own hair-care business. Following her marriage to Charles Walker in 1906, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker and marketed herself as an independent hairdresser and retailer of cosmetic creams. (“Madam” was adopted from women pioneers of the French beauty industry.<ref name=Success />) Her husband, who was also her business partner, provided advice on advertising and promotion; Sarah sold her products door to door, teaching other black women how to groom and style their hair.<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=BWA1210-11/> |

|||

A little context and review: Along the indelible color line that court cases like Plessy v. Ferguson drew, blacks in turn-of-the-century America were excluded from most trade unions and denied bank capital, resulting in trapped lives as sharecroppers or menial, low-wage earners. One of the only ways out, as my colleague Nancy Koehn and others reveal in their2007 study of Walker, was to start a business in a market segmented by Jim Crow. Hair care and cosmetics fit the bill. The start-up costs were low. Unlike today’s big multinationals, white businesses were slow to respond to blacks’ specific needs. And there was a slew of remedies to improve upon from well before slavery. Turnbo saw this opportunity and, in creating her “Poro” brand, seized it as part of a larger movement that witnessed the launch of some 10,000 to 40,000 black-owned businesses between 1883 and 1913. Now it was Sarah’s turn. |

|||

In 1906 Walker put her daughter in charge of the mail order operation in Denver while she and her husband traveled throughout the southern and eastern United States to expand the business.<ref name=bundles>{{cite journal|author=A'Lelia Bundles |title=Madam C.J. Walker: Business Savvy to Philanthropy|journal=eJournal USA|date=February 2012|volume=16|issue=6|pages=3–5|url=https://photos.state.gov/libraries/amgov/30145/publications-english/Black_Women_Leaders_eJ.pdf|accessdate=2015-03-01|publisher=U.S. Department of State}}</ref><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/><ref name=ingham/><ref>{{cite book |author1=Harold Evans |author2=Gail Buckland |author3=David Lefer |last-author-amp=yes | title=They Made America: From the Steam Engine to the Search Engine: Two Centuries of Innovators| location =New York| publisher=Little, Brown| year=2004| page = | url = | isbn =9780316277662 }}</ref> In 1908 Walker and her husband relocated to [[Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania]], where they opened a beauty parlor and established Lelia College to train "hair culturists." After closing the business in Denver in 1907, A'lelia ran the day-to-day operations from Pittsburgh, while Walker established a new base in [[Indianapolis]] in 1910.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Nancy F. Koehn |author2=Anne E. Dwojeski |author3=William Grundy |author4=Erica Helms |author5=Katherine Miller | title = Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur, Leader, and Philanthropist | publisher =Harvard Business School Publishing | series = | volume =9-807-145 | edition = | year =2007 | location =Boston | page =12 | url = | OCLC=154317207}}</ref> A'lelia also persuaded her mother to establish an office and beauty salon in [[New York City]]'s [[Harlem]] neighborhood in 1913.<ref name=Success>{{cite web |author= A'Lelia Bundles|title=Madam C. J. Walker’s Secrets to Success |publisher=Biography.com| date= |url =http://www.biography.com/news/madam-cj-walker-biography-facts |accessdate=2016-02-09}}</ref> |

|||

The Walker System |

|||

In 1910 Walker relocated her business to [[Indianapolis]], where she established the headquarters for the Madame C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. She initially purchased a house and factory at 640 North West Street.<ref name=GS361>Gugin and Saint Clair, p. 361.</ref> Walker later built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school to train her sales agents, and added a laboratory to help with research.<ref name=ingham/> She also assembled a competent staff that included [[Freeman Ransom]], [[Robert Lee Brokenburr]], [[Alice Kelly]], and [[Marjorie Joyner|Marjorie Stewart Joyner]], among others, to assist in managing the growing company.<ref name=BWA1210-11/> Many of her company's employees, including those in key management and staff positions, were women.<ref name=Success/> |

|||

While still a Turnbo agent, Sarah stepped out of her boss’ shadow in 1905 by relocating to Denver, where her sister-in-law’s family resided (apparently, she’d heard black women’s hair suffered in the Rocky Mountains’ high but dry air). C.J. soon followed, and in 1906 the two made it official — marriage No. 3 and a new business start — with Sarah officially changing her name to “Madam C.J. Walker.” |

|||

To increase her company's sales force, Walker trained other women to become "beauty culturists" using "The Walker System", her method of grooming that was designed to promote hair growth and to condition the scalp through the use of her products.<ref name=BWA1210-11/> Walker's system included a [[shampoo]], a [[pomade]] stated to help hair grow, strenuous brushing, and applying iron combs to hair. This method claimed to make lackluster and brittle hair become soft and luxurious.<ref name=bundles/><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> Walker's product line had several competitors. Similar products were produced in Europe and manufactured by other companies in the United States, which included her major rivals, Annie Turnbo Malone's Poro System and later, Sarah Spencer Washington's Apex System.<ref name=Science/> |

|||

Around the same time, she awoke from a dream, in which, in her words: “A big black man appeared to me and told me what to mix up for my hair. Some of the remedy was grown in Africa, but I sent for it, put it on my scalp, and in a few weeks my hair was coming in faster than it had ever fallen out.” It was to be called “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower.” Her initial investment: $1.25. |

|||

Between 1911 and 1919, during the height of her career, Walker and her company employed several thousand women as sales agents for its products.<ref name=indiana-history/> By 1917 the company claimed to have trained nearly 20,000 women.<ref name=GS361/> Dressed in a characteristic uniform of white shirts and black skirts and carrying black satchels, they visited houses around the United States and in the [[Caribbean]] offering Walker's hair pomade and other products packaged in tin containers carrying her image. Walker understood the power of advertising and brand awareness. Heavy advertising, primarily in African American newspapers and magazines, in addition to Walker's frequent travels to promote her products, helped make Walker and her products well known in the United States. Walker's name became even more widely known by the 1920s, after her death, as her company's business market expanded beyond the United States to [[Cuba]], [[Jamaica]], [[Haiti]], [[Panama]], and [[Costa Rica]].<ref name=bundles/><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/><ref name=Success/><ref name=Science>{{cite web| title=Madame C. J. Walker (Sarah Breedlove McWilliams Walker): Inventor, Businesswoman|work=The Faces of Science: African Americans in the Sciences|publisher=| date= |url = https://webfiles.uci.edu/mcbrown/display/walker.html |accessdate=2015-05-22}}</ref> |

|||

Sarah’s industry had its critics, among them the leading black institution-builder of the day, Booker T. Washington, who worried (to his credit) that hair-straighteners (and, worse, skin-bleaching creams) would lead to the internalization of white concepts of beauty. Perhaps she was mindful of this, for she was deft in communicating that her dream was not emulative of whites, but divinely inspired, and, like Turnbo’s “Poro Method,” African in origin. |

|||

In addition to training in sales and grooming, Walker showed other black women how to budget, build their own businesses, and encouraged them to become financially independent. In 1917, inspired by the model of the [[National Association of Colored Women]], Walker began organizing her sales agents into state and local clubs. The result was the establishment of the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents (predecessor to the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union of America).<ref name=indiana-history/> Its first annual conference convened in [[Philadelphia]] during the summer of 1917 with 200 attendees. The conference is believed to have been among the first national gatherings of women entrepreneurs to discuss business and commerce.<ref name=Riquier/><ref name=bundles /> During the convention Walker gave prizes to women who had sold the most products and brought in the most new sales agents. She also rewarded those who made the largest contributions to charities in their communities.<ref name=bundles/> |

|||

However, Walker went a step further. You see, the name Poro “came from a West African term for a devotional society, reflecting Turnbo’s concern for the welfare and the roots of the women she served,” according to a 2007 Harvard Business School case study. Whereas Turnbo took her product’s name from an African word, Madame C.J. claimed that the crucial ingredients for her product were African in origin. (And on top of that, she gave it a name uncomfortably close to Turnbo’s “Wonderful Hair Grower.”) |

|||

==Activism and philanthropy== |

|||

It wouldn’t be the only permanent sticking point between the two: Some claim it was Turnbo, not Walker, who became the first black woman to reach a million bucks. One thing about her startup was different, however: Walker’s brand, with the “Madam” in front, had the advantage of French cache, while defying many white people’s tendency to refer to black women by their first names, or, worse, as “Auntie.” |

|||

[[File:Madam CJ Walker home 67 Broadway Irvington NY jeh.jpg|thumb|House in Irvington]] |

|||

As Walker's wealth and notoriety increased, she became more vocal about her views. In 1912 Walker addressed an annual gathering of the [[National Negro Business League]] (NNBL) from the convention floor, where she declared: "I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.<ref name=GS361/>" The following year she addressed convention-goers from the podium as a keynote speaker.<ref name=bundles/><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> |

|||

Walker helped raise funds to establish a branch of the [[YMCA|Young Men’s Christian Association]] (YMCA) in Indianapolis's black community, pledging $1,000 to the building fund for the Senate Avenue YMCA. Walker also contributed scholarship funds to the [[Tuskegee University|Tuskegee Institute]]. Other beneficiaries included Indianapolis's Flanner House and [[Bethel A.M.E. Church (Indianapolis, Indiana)|Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church]]; Mary McLeod Bethune's Daytona Education and Industrial School for Negro Girls (which later became [[Bethune-Cookman University]]) in [[Daytona Beach, Florida]]; the [[Palmer Memorial Institute]] in [[North Carolina]]; and the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]]. Walker was also a patron of the arts.<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=bundles/> |

|||

Of course, many would-be entrepreneurs start off with a dream. The reason we’re still talking about Walker’s is her prescience, and her success in the span of just a dozen years. In pumping her “Wonderful Hair Grower” door-to-door, at churches and club gatherings, then through a mail-order catalog, Walker proved to be a marketing magician, and she sold her customers more than mere hair products. She offered them a lifestyle, a concept of total hygiene and beauty that in her mind would bolster them with pride for advancement. |

|||

About 1913 Walker's daughter, A'Lelia, moved to a new townhouse in Harlem, and in 1916 Walker joined her in New York, leaving the day-to-day operation of her company to her management team in Indianapolis.<ref name=Bundles-website/><ref name=GS361/> In 1917 Walker commissioned [[Vertner Tandy]], the first licensed black architect in [[New York City]] and a founding member of [[Alpha Phi Alpha]] fraternity, to design her house in [[Irvington-on-Hudson, New York]]. Walker intended for [[Villa Lewaro]], which cost $250,000 to build, to become a gathering place for community leaders and to inspire other African Americans to pursue their dreams.<ref name=Science/><ref>Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in ''Black Women in America'', v. II, p. 1213.</ref><ref name=TimesObit>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/1223.html |title =Wealthiest Negress Dead |work=[[New York Times]] |date=May 26, 1919 |accessdate=2015-03-01}}</ref> She moved into the house in May 1918 and hosted an opening event to honor [[Emmett Jay Scott]], at that time the Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs of the [[United States War Department|U.S. Department of War]].<ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> |

|||

To get the word out, Walker also was masterful in leveraging the power of America’s burgeoning independent black newspapers (in some cases, her ads kept them afloat). It was hard to miss Madam Walker whenever reading up on the latest news, and in her placements, she was a pioneer at using black women — actually, herself — as the faces in both her beforeand after shots, when others had typically reserved the latter for white women only (That was the dream, wasn’t it? the photos implied). |

|||

Walker became more involved in political matters after her move to New York. She delivered lectures on political, economic, and social issues at conventions sponsored by powerful black institutions. Her friends and associates included [[Booker T. Washington]], [[Mary McLeod Bethune]], and [[W. E. B. Du Bois]].<ref name=indiana-history/> During [[World War I]] Walker was a leader in the [[Circle For Negro War Relief]] and advocated for the establishment of a training camp for black army officers.<ref name=GS361/> In 1917 she joined the executive committee of New York chapter of the [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] (NAACP), which organized the [[Silent Parade|Silent Protest Parade]] on New York City's Fifth Avenue. The public demonstration drew more than 8,000 African Americans to protest a riot in East Saint Louis that killed thirty-nine African Americans.<ref name=bundles/> |

|||

At the same time, Walker had the foresight to incorporate in 1910, and even when she couldn’t attract big-name backers, she invested $10,000 of her own money, making herself sole shareholder of the new Walker Manufacturing Company, headquartered at a state-of-the-art factory and school in Indianapolis, itself a major distribution hub. |

|||

Profits from her business significantly impacted Walker's contributions to her political and philanthropic interests. In 1918 the [[National Association of Colored Women's Clubs]] (NACWC) honored Walker for making the largest individual contribution to help preserve [[Frederick Douglass]]’s [[Anacostia]] house.<ref>Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in ''Black Women in America'', v. II, p. 1212.</ref> Prior to her death in 1919, Walker pledged $5,000 (the equivalent of about $65,000 in 2012) to the NAACP's anti-[[lynching]] fund. At the time it was the largest gift from an individual that the NAACP had ever received. Walker bequeathed nearly $100,000 to orphanages, institutions, and individuals; her will directed two-thirds of future net profits of her estate to charity.<ref name=Philanthropy>{{cite web|title=Madam C. J. Walker |url =http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/hall_of_fame/madam_c._j._walker|website=The Philanthropy Hall of Fame|publisher=Philanthropy Roundtable|accessdate=1 March 2015}}</ref><ref name=bundles/><ref name=Success/> |

|||

Perhaps most important, Madam Walker transformed her customers into evangelical agents, who, for a handsome commission, multiplied her ability to reach new markets while providing them with avenues up out of poverty, much like Turnbo had provided her. In short order, Walker’s company had trained some 40,000 “Walker Agents” at an ever-expanding number of hair-culture colleges she founded or set up through already established black institutions. And there was a whole “Walker System” for them to learn, from vegetable shampoos to cold creams, witch hazel, diets and those controversial hot combs. |

|||

[[File:Madam C. J. Walker Grave 2009.JPG|thumb|right|The grave of Madam C. J. Walker]] |

|||

==Death and legacy== |

|||

Contrary to legend, Madam Walker didn’t invent the hot comb. According to A’Lelia Bundles’ biography of Walker in Black Women in America, a Frenchman, Marcel Grateau, popularized it in Europe in the 1870s, and even Sears and Bloomingdale’s advertised the hair-straightening styling tool in their catalogs in the 1880s. But Walker did improve the hot comb with wider teeth, and as a result of its popularity, sales sizzled. |

|||

Walker died on May 25, 1919, from kidney failure and complications of [[hypertension]] at the age of fifty-one.<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=GS361/><ref name=TimesObit/> Walker's remains are interred in [[Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York)|Woodlawn Cemetery]] in [[The Bronx]], New York City.<ref>{{cite web| title =Woodlawn Cemetery–Madam Walker’s Burial Place–Named National Historic Landmark |url=https://madamcjwalker.wordpress.com/tag/woodlawn-cemetery/ | work = | publisher = | date = | accessdate =2016-02-02}}</ref> |

|||

At the time of her death Walker was considered to be the wealthiest African American woman in America. She was eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America, but Walker's estate was only worth an estimated $600,000 (approximately $8 million in present-day dollars) upon her death.<ref name="Philanthropy"/> According to Walker's ''New York Times'' obituary, "she said herself two years ago [in 1917] that she was not yet a millionaire, but hoped to be some time."<ref name=TimesObit /> At the time of Walker's death, the average American's annual salary was $750.<ref>https://bizfluent.com/info-7769323-history-american-income.html</ref> Her daughter, [[A'Lelia Walker]], became the president of the [[Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company]].<ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> |

|||

Careful to position herself as a “hair culturalist,” Walker was building a vast social network of consumer-agents united by their dreams of looking — and thus feeling — different, from the heartland of America to the Caribbean and parts of Central America. Whether it stimulated emulation or empowerment was the debate — and in many ways it still is. One thing, though, was for sure: It was big business. No — huge! “Open your own shop; secure prosperity and freedom,” one of Madam Walker’s brochures announced. Those who enrolled in “Lelia College” even received a diploma. |

|||

Walker's personal papers are preserved at the [[Indiana Historical Society]] in Indianapolis.<ref name=Riquier/> Her legacy also continues through two properties listed on the [[National Register of Historic Places]]: [[Villa Lewaro]] in [[Irvington, New York]], and the [[Madame Walker Theatre Center]] in Indianapolis. Villa Lewaro was sold following A'Lelia Walker's death to a fraternal organization called the Companions of the Forest in America in 1932. The house was listed on the [[National Register of Historic Places]] in 1979. The [[National Trust for Historic Preservation]] has designated the privately owned property a National Treasure.<ref>{{cite web| author=Jessica Pumphrey | title =Sign the Pledge to Protect Villa Lewaro – And Learn How You Can Tour It | work = | publisher =National Trust for Historic Preservation | date =2014-10-24 | url = https://savingplaces.org/stories/pledge-protect-villa-lewaro-get-tour#.VrT4TWBEg2w | format = | accessdate =2016-02-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite web| author=Brent Leggs| |

|||

If imitation is the highest form of flattery, Walker had the Mona Lisa of black-beauty brands. Among the most ridiculous knockoffs was the white-owned “Madam Mamie Hightower” company. To keep others at bay, Walker insisted on placing a special seal with her likeness on every package. So successful, so quickly, was Walker in solidifying her presence in the consumer’s mind that when her marriage to C.J. fell apart in 1912, she insisted on keeping his name. After all, she’d already made it more famous. |

|||

url=http://www.preservationnation.org/assets/pdfs/saving-places/Preserving-Villa-Lewaro-National-Treasure-Madam-C-J-Walker-Estate.pdf| title =Envisioning Villa Lewaro's Future| publisher=[[National Trust for Historic Preservation]]| date=2014|accessdate =2016-02-19}}</ref> Indianapolis's Walker Manufacturing Company headquarters building, renamed the Madame Walker Theatre Center, opened in December 1927; it included the company's offices and factory as well as a theater, beauty school, hair salon and barbershop, restaurant, drugstore, and a ballroom for the community. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.<ref name=Success/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://focus.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/80000062 |title=National Register Digital Assets: Madame C. J. Walker Building |date= |publisher=National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior}}</ref> |

|||

In 2006, playwright and director [[Regina Taylor]] wrote The ''Dreams of Sarah Breedlove,'' recounting the history of Walker’s struggles and success.<ref name=":0">"Regina Taylor Brings the Story of Madam C.J. Walker to the Stage." Jet Jul 10 2006: 62-3. ProQuest. 6 Mar. 2016 .</ref> The play premiered at the [[Goodman Theatre|Goodman Theater]] in Chicago.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.goodmantheatre.org/season/0506/the-dreams-of-sarah-breedlove/|title=The Dreams of Sarah Breedlove {{!}} Goodman Theater {{!}} Chicago|website=www.goodmantheatre.org|access-date=2016-03-06}}</ref> Actress [[L. Scott Caldwell]] played the role of Walker.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

To keep her agents more loyal, Walker organized them into a national association and offered cash incentives to those who promoted her values. In the same way, she organized the National Negro Cosmetics Manufacturers Association in 1917. “I am not merely satisfied in making money for myself,” Walker said in 1914. “I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of women of my race.” And for her it wasn’t just about pay; Walker wanted to train her fellow black women to be refined. As she explained in her 1915 manual, Hints to Agents, “Open your windows — air it well … Keep your teeth clean in order that [your] breath might be sweet … See that your fingernails are kept clean, as that is a mark of refinement.” |

|||

On March 4, 2016, skincare and haircare company Sundial Brands launched a collaboration with [[Sephora]] in honor of Walker’s legacy. The launch, titled “Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture”, comprised four collections and focused on the use of natural ingredients to care for different types of hair.<ref>"Sundial Brands Enters Prestige Hair Category with Historic Launch of Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture Exclusively at Sephora." PR Newswire Feb 23 2016ProQuest. 6 Mar. 2016 .</ref> As of 2017, actress [[Octavia Spencer]] has committed to portray Walker in a TV series based on the biography of Walker by A’Lelia Bundles, Walker's great-great-granddaughter.<ref name=nypost>Lanert, Raquel (February 18, 2017) [https://nypost.com/2017/02/18/manse-built-by-americas-first-self-made-millionairess-in-jeopardy/ "Manse built by America’s first self-made millionairess in jeopardy"] ''[[New York Post]]''</ref> |

|||

Reading this, I instantly thought of Booker T. Washington, “the wizard of Tuskegee,” who, while troubled by the black beauty industry, shared Walker’s obsession with cleanliness. In fact, Washington made it critical to his school’s curriculum, preaching “the gospel of the toothbrush,” writes Suellen Hoy in her interesting history, Chasing Dirt: The American Pursuit of Cleanliness. “I never see … an unpainted or unwhitewashed house that I do not want to paint or whitewash it,” Washington himself wrote in his memoir, Up From Slavery. |

|||

==Tributes== |

|||

I have no doubt this topic would’ve made for interesting conversation between Washington and Walker (after all, having come from similar places, weren’t they after similar things with not dissimilar risks?). Yet, try as Walker did to curry Washington’s favor, her initial forays only met his grudging acknowledgment, even though many of the wives Washington knew, including his own — the wives of the very ministers denouncing products like Walker’s — were dreaming of the same straight styles. |

|||

Various scholarships and awards have been named in Walker's honour: |

|||

* The Madam C. J Walker Business and Community Recognition Awards are sponsored by the [[National Coalition of 100 Black Women]], Oakland/Bay Area chapter. An annual luncheon honours Walker and awards outstanding women in the community with scholarships.<ref>{{cite web|title=17th Annual Madam C. J. Walker 2015 Luncheon |url= |

|||

http://www.onehundredblackwomen.com/madame-c-j-walker/17th-annual-mcjw-2015-luncheon/|publisher=National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Inc., Oakland/Bay Area Chapter|accessdate=2016-02-05}}</ref> |

|||

* Spirit Awards have sponsored the Madame Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis. Established as a tribute to Walker, the annual awards have honoured national leaders in entrepreneurship, philanthropy, civic engagement, and the arts since 2006. Awards presented to individuals include the Madame C. J Walker Heritage Award as well as young entrepreneur and legacy prizes.<ref name=awards>{{cite web | title=About the Spirit Awards | url=http://www.thewalkertheatre.org/spirit-awards/nomination-form | publisher=Madame Walker Theatre Center | year=2016 | accessdate=2016-02-04}}</ref> |

|||

Walker was inducted into the [[National Women's Hall of Fame]] in [[Seneca, New York]], in 1993.<ref>{{cite web| title =Madam C. J. Walker | work = | publisher =National Women’s Hall of Fame | date = | url = https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/madam-c-j-walker/| format = | accessdate =2016-02-10}}</ref> In 1998 the [[United States Postal Service|U.S. Postal Service]] issued a Madam Walker commemorative stamp as part of its Black Heritage Series.<ref name=GS361/><ref>[http://www.usstampgallery.com/view.php?id=76b046e9928ba079d703ec17fae2813be2625b64&Madam_CJ_Walker&st=madame%20walker&ss=&t=&s=4&syear=&eyear= US Stamp Gallery]</ref> |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

'''Nonfiction biographies''' (based on primary source documents) |

|||

*{{cite book| author=[[A'Lelia Bundles|Bundles, A'Lelia Perry]]| title =Madam Walker Theatre Center: An Indianapolis Treasure |publisher =Arcadia Publishing| series =Images of America | volume = | edition = |year=2013 |location =Charleston, SC |isbn=1-4671-1087-6}} |

|||

*{{cite book| author=Bundles, A'Lelia Perry|title=Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur |publisher=Chelsea House| series =Black Americans of Achievement | volume = | edition =Legacy |year=2008| location =New York | isbn=978-1-60413-072-0}} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=[[Penny Colman|Colman, Penny]] | title =Madam C. J. Walker: Building a Business Empire |publisher=The Millbrook Press | series =Gateway Biography | volume = | edition = | year =1994 |location =Brookfield, CT | pages = | url = | isbn =9781562943387}} |

|||

*{{cite book|editor1-last=Sullivan|editor1-first=Otha Richard|editor2-last=Haskins|editor2-first=James| editor2link =James Haskins|title=African American Women Scientists and Inventors|date=2002|publisher=Jossey-Bass|location=San Francisco|isbn=9780471387077|pages=25-30|chapter=Madam C.J. Walker (1867–1919)}} |

|||

'''Fiction/novels''' |

|||

*{{cite book| author=[[Tananarive Due|Due, Tananarive]] |title=The Black Rose: The Dramatic Story of Madam C. J. Walker, America's First Black Female Millionaire |publisher=Ballantine Books |year=2000|isbn=0-345-44156-7}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

*{{Findagrave|18239}} |

|||

*{{YouTube|AuYjx7zDBas|Madam C J Walker-Successful Business Woman}} |

|||

*{{YouTube|Kk-17lfCeGs|Stanley Nelson Interviews Madam C. J. Walker's Great Grand Daughter}} (Walker's political activism and philanthropy) |

|||

*{{cite video| people = | title =On Her Own Ground: Madame C. J. Walker | medium = | publisher =C-Span| location = | date =2001-01-27 | url=http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/CJ}} (Book discussion) |

|||

*{{YouTube|p3qjlLYszEI|Madam Walker Research in the National Archives}} |

|||

*{{YouTube|-O4BGrMcD4o|The Legacy of Madam Walker}} (Part 1) |

|||

*{{YouTube|2lXl8XKfZ-8|Madam C J Walker}} (Indiana Bicentennial Minute, 2016) |

|||

*{{YouTube|n4knvT_-IO8|Madam C J Walker Estate}} (Part 1 of 5) Villa Lewaro, Irvington-on-Hudson, New York |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Walker, Madam C. J.}} |

|||

[[Category:Madam C. J. Walker| ]] |

|||

[[Category:1867 births]] |

|||

[[Category:1919 deaths]] |

|||

[[Category:American philanthropists]] |

|||

[[Category:American millionaires]] |

|||

[[Category:American women in business]] |

|||

[[Category:Businesspeople from Louisiana]] |

|||

[[Category:African-American company founders]] |

|||

[[Category:American company founders]] |

|||

[[Category:Deaths from hypertension]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Madison Parish, Louisiana]] |

|||

[[Category:People from St. Louis]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Denver]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Indianapolis]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Irvington, New York]] |

|||

[[Category:Beauticians]] |

|||

Revision as of 00:34, 29 January 2018

Madam C. J. Walker | |

|---|---|

Walker in 1903 | |

| Born | Sarah Breedlove December 23, 1867 Delta, Louisiana, United States |

| Died | May 25, 1919 (aged 51) Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, United States |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Businesswoman, hair-care entrepreneur, Philanthropist, and Activist |

| Spouse(s) | Moses McWilliams (married 1882–1887) John Davis (married 1894 – c. 1903) Charles Joseph Walker (married 1906–1912) |

| Children | A'Lelia Walker |

| Website | www |

Sarah Breedlove (December 23, 1867 – May 25, 1919), known as Madam C. J. Walker, was an African American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and a political and social activist. Eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America,[1] she became one of the wealthiest African American women in the country, "the world's most successful female entrepreneur of her time," and one of the most successful African-American business owners ever.[2]

Walker made her fortune by developing and marketing a line of beauty and hair products for black women through Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, the successful business she founded. Walker was also known for her philanthropy and activism. She made financial donations to numerous organizations and became a patron of the arts. Villa Lewaro, Walker’s lavish estate in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, served as a social gathering place for the African American community.

Early life

Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, near Delta, Louisiana, to Owen and Minerva (Anderson) Breedlove.[3][4] Sarah was one of six children, which included an older sister, Louvenia, and four brothers: Alexander, James, Solomon, and Owen Jr. Breedlove's parents and her older siblings were enslaved on Robert W. Burney's Madison Parish plantation, but Sarah was the first child in her family born into freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. Her mother died, possibly from cholera, in 1872; her father remarried, but he died within a few years.[citation needed] Orphaned at the age of seven, Sarah moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, at the age of ten and worked as a domestic. Prior to her first marriage, she lived with her older sister, Louvenia, and brother-in-law, Jesse Powell.[3][5]

Marriage and family

In 1882, at the age of fourteen, Sarah married Moses McWilliams, possibly to escape mistreatment from her brother-in-law.[3] Sarah and Moses had one daughter, Lelia McWilliams, born on June 6, 1885. When Moses died in 1887, Sarah was twenty; Lelia was two years old.[5][6] Sarah remarried in 1894, but left her second husband, John Davis, around 1903 and moved to Denver, Colorado, in 1905.[7][8]

In January 1906, Sarah married Charles Joseph Walker, a newspaper advertising salesman she had known in Missouri. Through this marriage, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker. The couple divorced in 1912; Charles died in 1926. Lelia McWilliams adopted her stepfather's surname and became known as A'Lelia Walker.[5][9][10]

Career

In 1888 Sarah and her daughter moved to Saint Louis, Missouri, where three of her brothers lived. Sarah found work as a laundress, barely earning more than a dollar a day, but she was determined to make enough money to provide her daughter with a formal education.[11][12] During the 1880s, Breedlove lived in a community where ragtime music was developed—she sang at the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and started to yearn for an educated life as she watched the community of women at her church.[1] As was common among black women of her era, Sarah experienced severe dandruff and other scalp ailments, including baldness, due to skin disorders and the application of harsh products such as lye that were included in soaps to cleanse hair and wash clothes. Other contributing factors to her hair loss included poor diet, illnesses, and infrequent bathing and hair washing during a time when most Americans lacked indoor plumbing, central heating and electricity.[10][13][14]

Initially, Sarah learned about hair care from her brothers, who were barbers in Saint Louis.[13] Around the time of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World's Fair at St. Louis in 1904), she became a commission agent selling products for Annie Turnbo Malone, an African American hair-care entrepreneur and owner of the Poro Company.[3] While working for Malone, who would later become Walker’s largest rival in the hair-care industry,[1] Sarah began to adapt her knowledge of hair and hair products to develop her own product line.[9]

In July 1905, when she was thirty-seven years old, Sarah and her daughter moved to Denver, Colorado, where she continued to sell products for Malone and develop her own hair-care business. Following her marriage to Charles Walker in 1906, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker and marketed herself as an independent hairdresser and retailer of cosmetic creams. (“Madam” was adopted from women pioneers of the French beauty industry.[16]) Her husband, who was also her business partner, provided advice on advertising and promotion; Sarah sold her products door to door, teaching other black women how to groom and style their hair.[5][9]

In 1906 Walker put her daughter in charge of the mail order operation in Denver while she and her husband traveled throughout the southern and eastern United States to expand the business.[11][13][14][17] In 1908 Walker and her husband relocated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where they opened a beauty parlor and established Lelia College to train "hair culturists." After closing the business in Denver in 1907, A'lelia ran the day-to-day operations from Pittsburgh, while Walker established a new base in Indianapolis in 1910.[18] A'lelia also persuaded her mother to establish an office and beauty salon in New York City's Harlem neighborhood in 1913.[16]

In 1910 Walker relocated her business to Indianapolis, where she established the headquarters for the Madame C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. She initially purchased a house and factory at 640 North West Street.[19] Walker later built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school to train her sales agents, and added a laboratory to help with research.[14] She also assembled a competent staff that included Freeman Ransom, Robert Lee Brokenburr, Alice Kelly, and Marjorie Stewart Joyner, among others, to assist in managing the growing company.[9] Many of her company's employees, including those in key management and staff positions, were women.[16]

To increase her company's sales force, Walker trained other women to become "beauty culturists" using "The Walker System", her method of grooming that was designed to promote hair growth and to condition the scalp through the use of her products.[9] Walker's system included a shampoo, a pomade stated to help hair grow, strenuous brushing, and applying iron combs to hair. This method claimed to make lackluster and brittle hair become soft and luxurious.[11][13] Walker's product line had several competitors. Similar products were produced in Europe and manufactured by other companies in the United States, which included her major rivals, Annie Turnbo Malone's Poro System and later, Sarah Spencer Washington's Apex System.[20]

Between 1911 and 1919, during the height of her career, Walker and her company employed several thousand women as sales agents for its products.[5] By 1917 the company claimed to have trained nearly 20,000 women.[19] Dressed in a characteristic uniform of white shirts and black skirts and carrying black satchels, they visited houses around the United States and in the Caribbean offering Walker's hair pomade and other products packaged in tin containers carrying her image. Walker understood the power of advertising and brand awareness. Heavy advertising, primarily in African American newspapers and magazines, in addition to Walker's frequent travels to promote her products, helped make Walker and her products well known in the United States. Walker's name became even more widely known by the 1920s, after her death, as her company's business market expanded beyond the United States to Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Panama, and Costa Rica.[11][13][16][20]

In addition to training in sales and grooming, Walker showed other black women how to budget, build their own businesses, and encouraged them to become financially independent. In 1917, inspired by the model of the National Association of Colored Women, Walker began organizing her sales agents into state and local clubs. The result was the establishment of the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents (predecessor to the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union of America).[5] Its first annual conference convened in Philadelphia during the summer of 1917 with 200 attendees. The conference is believed to have been among the first national gatherings of women entrepreneurs to discuss business and commerce.[10][11] During the convention Walker gave prizes to women who had sold the most products and brought in the most new sales agents. She also rewarded those who made the largest contributions to charities in their communities.[11]

Activism and philanthropy

As Walker's wealth and notoriety increased, she became more vocal about her views. In 1912 Walker addressed an annual gathering of the National Negro Business League (NNBL) from the convention floor, where she declared: "I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.[19]" The following year she addressed convention-goers from the podium as a keynote speaker.[11][13]

Walker helped raise funds to establish a branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in Indianapolis's black community, pledging $1,000 to the building fund for the Senate Avenue YMCA. Walker also contributed scholarship funds to the Tuskegee Institute. Other beneficiaries included Indianapolis's Flanner House and Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church; Mary McLeod Bethune's Daytona Education and Industrial School for Negro Girls (which later became Bethune-Cookman University) in Daytona Beach, Florida; the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina; and the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in Georgia. Walker was also a patron of the arts.[5][11]

About 1913 Walker's daughter, A'Lelia, moved to a new townhouse in Harlem, and in 1916 Walker joined her in New York, leaving the day-to-day operation of her company to her management team in Indianapolis.[4][19] In 1917 Walker commissioned Vertner Tandy, the first licensed black architect in New York City and a founding member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, to design her house in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York. Walker intended for Villa Lewaro, which cost $250,000 to build, to become a gathering place for community leaders and to inspire other African Americans to pursue their dreams.[20][21][22] She moved into the house in May 1918 and hosted an opening event to honor Emmett Jay Scott, at that time the Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs of the U.S. Department of War.[13]

Walker became more involved in political matters after her move to New York. She delivered lectures on political, economic, and social issues at conventions sponsored by powerful black institutions. Her friends and associates included Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, and W. E. B. Du Bois.[5] During World War I Walker was a leader in the Circle For Negro War Relief and advocated for the establishment of a training camp for black army officers.[19] In 1917 she joined the executive committee of New York chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which organized the Silent Protest Parade on New York City's Fifth Avenue. The public demonstration drew more than 8,000 African Americans to protest a riot in East Saint Louis that killed thirty-nine African Americans.[11]

Profits from her business significantly impacted Walker's contributions to her political and philanthropic interests. In 1918 the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC) honored Walker for making the largest individual contribution to help preserve Frederick Douglass’s Anacostia house.[23] Prior to her death in 1919, Walker pledged $5,000 (the equivalent of about $65,000 in 2012) to the NAACP's anti-lynching fund. At the time it was the largest gift from an individual that the NAACP had ever received. Walker bequeathed nearly $100,000 to orphanages, institutions, and individuals; her will directed two-thirds of future net profits of her estate to charity.[1][11][16]

Death and legacy

Walker died on May 25, 1919, from kidney failure and complications of hypertension at the age of fifty-one.[5][19][22] Walker's remains are interred in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.[24]

At the time of her death Walker was considered to be the wealthiest African American woman in America. She was eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America, but Walker's estate was only worth an estimated $600,000 (approximately $8 million in present-day dollars) upon her death.[1] According to Walker's New York Times obituary, "she said herself two years ago [in 1917] that she was not yet a millionaire, but hoped to be some time."[22] At the time of Walker's death, the average American's annual salary was $750.[25] Her daughter, A'Lelia Walker, became the president of the Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company.[13]

Walker's personal papers are preserved at the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis.[10] Her legacy also continues through two properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Villa Lewaro in Irvington, New York, and the Madame Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis. Villa Lewaro was sold following A'Lelia Walker's death to a fraternal organization called the Companions of the Forest in America in 1932. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has designated the privately owned property a National Treasure.[26][27] Indianapolis's Walker Manufacturing Company headquarters building, renamed the Madame Walker Theatre Center, opened in December 1927; it included the company's offices and factory as well as a theater, beauty school, hair salon and barbershop, restaurant, drugstore, and a ballroom for the community. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[16][28]

In 2006, playwright and director Regina Taylor wrote The Dreams of Sarah Breedlove, recounting the history of Walker’s struggles and success.[29] The play premiered at the Goodman Theater in Chicago.[30] Actress L. Scott Caldwell played the role of Walker.[29]

On March 4, 2016, skincare and haircare company Sundial Brands launched a collaboration with Sephora in honor of Walker’s legacy. The launch, titled “Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture”, comprised four collections and focused on the use of natural ingredients to care for different types of hair.[31] As of 2017, actress Octavia Spencer has committed to portray Walker in a TV series based on the biography of Walker by A’Lelia Bundles, Walker's great-great-granddaughter.[32]

Tributes

Various scholarships and awards have been named in Walker's honour:

- The Madam C. J Walker Business and Community Recognition Awards are sponsored by the National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Oakland/Bay Area chapter. An annual luncheon honours Walker and awards outstanding women in the community with scholarships.[33]

- Spirit Awards have sponsored the Madame Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis. Established as a tribute to Walker, the annual awards have honoured national leaders in entrepreneurship, philanthropy, civic engagement, and the arts since 2006. Awards presented to individuals include the Madame C. J Walker Heritage Award as well as young entrepreneur and legacy prizes.[34]

Walker was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca, New York, in 1993.[35] In 1998 the U.S. Postal Service issued a Madam Walker commemorative stamp as part of its Black Heritage Series.[19][36]

References

- ^ a b c d e "Madam C. J. Walker". The Philanthropy Hall of Fame. Philanthropy Roundtable. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ Glaeser, Edward (2011), Triumph of the City: How Our Best Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier, New York: Penguin Press, p. 75, ISBN 978-1-59420-277-3

- ^ a b c d Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in Black Women in America, v. II, p. 1209.

- ^ a b Bundles, A’Lelia. "Madam C.J. Walker". Madame C.J. Walker. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Madam C. J. Walker". Indiana Historical Society. Retrieved 2015-02-28.

- ^ A'lelia Bundles (2014). "Biography of Madam C. J. Walker". National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Inc., Oakland/Bay Area Chapter. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ^ Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "The Philanthropy Hall of Fame: Madam C. J. Walker". Philanthropy Roundtable. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ^ a b c d e Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in Black Women in America, v. II, pp. 1210–11.

- ^ a b c d Andrea Riquier (2015-02-24). "Madam Walker Went from Laundress to Success". Investor's Business Daily. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j A'Lelia Bundles (February 2012). "Madam C.J. Walker: Business Savvy to Philanthropy" (PDF). eJournal USA. 16 (6). U.S. Department of State: 3–5. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ^ Editors. "Madam C.J. Walker Biography". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 2016-02-15.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h A'Lelia Bundles (2001). On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-7434-3172-3.

- ^ a b c John N. Ingham (February 2000). "Madame C. J. Walker". American National Biography Online.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) (subscription required) - ^ "Madam C.J. Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower product container". The Indianapolis Public Library. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f A'Lelia Bundles. "Madam C. J. Walker's Secrets to Success". Biography.com. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- ^ Harold Evans; Gail Buckland; David Lefer (2004). They Made America: From the Steam Engine to the Search Engine: Two Centuries of Innovators. New York: Little, Brown. ISBN 9780316277662.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Nancy F. Koehn; Anne E. Dwojeski; William Grundy; Erica Helms; Katherine Miller (2007). Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur, Leader, and Philanthropist. Vol. 9-807-145. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing. p. 12. OCLC 154317207.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gugin and Saint Clair, p. 361.

- ^ a b c "Madame C. J. Walker (Sarah Breedlove McWilliams Walker): Inventor, Businesswoman". The Faces of Science: African Americans in the Sciences. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in Black Women in America, v. II, p. 1213.

- ^ a b c "Wealthiest Negress Dead". New York Times. May 26, 1919. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ^ Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in Black Women in America, v. II, p. 1212.

- ^ "Woodlawn Cemetery–Madam Walker's Burial Place–Named National Historic Landmark". Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ^ https://bizfluent.com/info-7769323-history-american-income.html

- ^ Jessica Pumphrey (2014-10-24). "Sign the Pledge to Protect Villa Lewaro – And Learn How You Can Tour It". National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ^ Brent Leggs (2014). "Envisioning Villa Lewaro's Future" (PDF). National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ^ "National Register Digital Assets: Madame C. J. Walker Building". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b "Regina Taylor Brings the Story of Madam C.J. Walker to the Stage." Jet Jul 10 2006: 62-3. ProQuest. 6 Mar. 2016 .

- ^ "The Dreams of Sarah Breedlove | Goodman Theater | Chicago". www.goodmantheatre.org. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ^ "Sundial Brands Enters Prestige Hair Category with Historic Launch of Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture Exclusively at Sephora." PR Newswire Feb 23 2016ProQuest. 6 Mar. 2016 .

- ^ Lanert, Raquel (February 18, 2017) "Manse built by America’s first self-made millionairess in jeopardy" New York Post

- ^ "17th Annual Madam C. J. Walker 2015 Luncheon". National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Inc., Oakland/Bay Area Chapter. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ^ "About the Spirit Awards". Madame Walker Theatre Center. 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ^ "Madam C. J. Walker". National Women’s Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ^ US Stamp Gallery

Further reading

Nonfiction biographies (based on primary source documents)

- Bundles, A'Lelia Perry (2013). Madam Walker Theatre Center: An Indianapolis Treasure. Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 1-4671-1087-6.

- Bundles, A'Lelia Perry (2008). Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur. Black Americans of Achievement (Legacy ed.). New York: Chelsea House. ISBN 978-1-60413-072-0.

- Colman, Penny (1994). Madam C. J. Walker: Building a Business Empire. Gateway Biography. Brookfield, CT: The Millbrook Press. ISBN 9781562943387.

- Sullivan, Otha Richard; Haskins, James, eds. (2002). "Madam C.J. Walker (1867–1919)". African American Women Scientists and Inventors. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. pp. 25–30. ISBN 9780471387077.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editor2link=ignored (|editor-link2=suggested) (help)

Fiction/novels

- Due, Tananarive (2000). The Black Rose: The Dramatic Story of Madam C. J. Walker, America's First Black Female Millionaire. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-44156-7.

External links

- Madam C. J. Walker at Find a Grave

- Madam C J Walker-Successful Business Woman on YouTube

- Stanley Nelson Interviews Madam C. J. Walker's Great Grand Daughter on YouTube (Walker's political activism and philanthropy)

- On Her Own Ground: Madame C. J. Walker. C-Span. 2001-01-27. (Book discussion)

- Madam Walker Research in the National Archives on YouTube

- The Legacy of Madam Walker on YouTube (Part 1)

- Madam C J Walker on YouTube (Indiana Bicentennial Minute, 2016)

- Madam C J Walker Estate on YouTube (Part 1 of 5) Villa Lewaro, Irvington-on-Hudson, New York

- Madam C. J. Walker

- 1867 births

- 1919 deaths

- American philanthropists

- American millionaires

- American women in business

- Businesspeople from Louisiana

- African-American company founders

- American company founders

- Deaths from hypertension

- People from Madison Parish, Louisiana

- People from St. Louis

- People from Denver

- People from Indianapolis

- People from Irvington, New York

- Beauticians