Destruction of country houses in 20th-century Britain: Difference between revisions

| Line 156: | Line 156: | ||

Following [[World War II]], many owners of vast houses faced an dilemma, often they had already disposed of minor country to preserve the principal seat, now that seat too was in jeopardy. The principal house was more than just a dwelling; built when the family was at the height of its power, wealth and glory, it represented the family's history and status it was an integral part of the family's being and needed to be preserved, even if this meant "entering trade", a prospect which would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier. |

Following [[World War II]], many owners of vast houses faced an dilemma, often they had already disposed of minor country to preserve the principal seat, now that seat too was in jeopardy. The principal house was more than just a dwelling; built when the family was at the height of its power, wealth and glory, it represented the family's history and status it was an integral part of the family's being and needed to be preserved, even if this meant "entering trade", a prospect which would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier. |

||

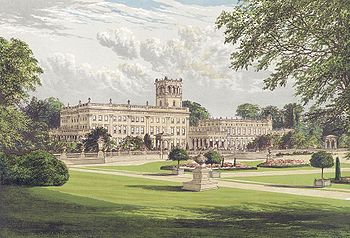

[[File:SAVEMentmore.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[SAVE]]'s campaign to save Mentmore Towers in 1974, was unsuccessful, the priceless contents were sold, and now dispersed over the word, and the house sold and allowed to decay. Today, 36 years after it ceased to be a private house, it lies empty, "[[Buildings at Risk Register|at risk]]" and facing an uncertain future.]] |

[[:File:SAVEMentmore.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[SAVE]]'s campaign to save Mentmore Towers in 1974, was unsuccessful, the priceless contents were sold, and now dispersed over the word, and the house sold and allowed to decay. Today, 36 years after it ceased to be a private house, it lies empty, "[[Buildings at Risk Register|at risk]]" and facing an uncertain future.]]<!--Non free file removed by DASHBot--> |

||

This is can be exemplified by the business ventures executed by the [[Marquess of Bath]] at [[Longleat House]]. Reacquiring occupation of this enormous 16th century mansion, in a state of poor repair, following requisition during World War II, the marquess was faced with death duties of £700,000, the marquess through the house open to the paying public and kept the proceeds himself to fund the mansion. In 1966, to keep attendance numbers high, the peer went a step further and introduced lions to the park, thus creating Britain's' first [[Longleat Safari Park|safari park]]. After the initial opening of Longleat, the Dukes of Marlborough, Devonshire and Bedford threw open the doors of [[Blenheim Palace]], [[Chatsworth House]] and what remained of [[Woburn Abbey]]. With the example and precedent of "trade" set by those at the top of the aristocratic pyramid, within a few years hundreds of Britain's country houses were open two or three days a week to public eager to see the rooms which a few years earlier their ancestors had cleaned. By 1992, 600 "stately homes" were visited annually by 50 million members of the paying public.<ref>Vickers, obituary</ref> Stately homes were now big business, but opening a few rooms and novelties in the park alone were not going to fund the houses beyond the final decades of the twentieth century. Even during the stately home boom years of the 1960s and 1970s historic houses were still having their contents sold, being demolished or if permission to demolish was not forthcoming being left to dereliction and ruin. |

This is can be exemplified by the business ventures executed by the [[Marquess of Bath]] at [[Longleat House]]. Reacquiring occupation of this enormous 16th century mansion, in a state of poor repair, following requisition during World War II, the marquess was faced with death duties of £700,000, the marquess through the house open to the paying public and kept the proceeds himself to fund the mansion. In 1966, to keep attendance numbers high, the peer went a step further and introduced lions to the park, thus creating Britain's' first [[Longleat Safari Park|safari park]]. After the initial opening of Longleat, the Dukes of Marlborough, Devonshire and Bedford threw open the doors of [[Blenheim Palace]], [[Chatsworth House]] and what remained of [[Woburn Abbey]]. With the example and precedent of "trade" set by those at the top of the aristocratic pyramid, within a few years hundreds of Britain's country houses were open two or three days a week to public eager to see the rooms which a few years earlier their ancestors had cleaned. By 1992, 600 "stately homes" were visited annually by 50 million members of the paying public.<ref>Vickers, obituary</ref> Stately homes were now big business, but opening a few rooms and novelties in the park alone were not going to fund the houses beyond the final decades of the twentieth century. Even during the stately home boom years of the 1960s and 1970s historic houses were still having their contents sold, being demolished or if permission to demolish was not forthcoming being left to dereliction and ruin. |

||

Revision as of 05:02, 3 December 2010

add here a scan of the CL advert - 1911.

The Lost houses of Britain are a collection of mostly country houses of varying architectural merit which were demolished during the 20th century. The final chapter in the history of these often now-forgotten houses has been described as a cultural tragedy.[2]

Two years before the advent of World War I on 4 May 1912, the British magazine, Country Life, carried a seemingly unremarkable advertisement; the roofing balustrade and urns from the roof of Trentham Hall could be purchased for £200. Trentham Hall, one of Britain's great ducal country houses, had been demolished with little public comment or interest. It was its owner's property, to do with as he wished – and he wished to demolish it. There was no reason for public interest or concern, the same magazine had frequently over the past year published in-depth articles on new country houses being built, designed by fashionable architects such as Lutyens. As far as general opinion was concerned England's great houses came and they went; so long as their numbers remained, continuing to provide mass employment, the public were not largely concerned.

The English aristocracy had been demolishing their country houses since the 15th century, when comfort replaced fortification as an essential need. For many, demolishing and rebuilding their country homes became a lifelong hobby, in particular during the 18th century when it became fashionable to take the Grand Tour and return home with art treasures, supposedly brought from classical civilizations. During the 19th century, many houses were enlarged to accommodate the increasing armies of servants needed to create the famed country house lifestyle. Less than a century later, this often meant they were of an unmanageable size.

However, in the early 20th century, something changed and the demolishing accelerated while rebuilding largely ceased. The losses were not confined to England, but spread throughout Britain. By the end of the century, even some of the "new" country houses by Lutyens had been demolished. The reasons are manifold: social, political and most importantly, financial. In rural areas of Britain, the loss of the country houses was tantamount to a social revolution.

Since 1900, 378 architecturally important country houses have been demolished in Scotland alone, 200 of these since 1945.[3][4] This number can be applied pro-rata to both England and Wales. Included in the destruction were works by Robert Adam, including Balbardie House and the monumental Hamilton Palace. One firm, Charles Brand of Dundee, demolished at least 56 country houses in Scotland in the 20 years between 1945 and 1965.[5]

The destruction which began as a trickle just prior to World War I had become a tidal wave by 1955, when one house was demolished every five days.[6]. Following World War II, Britain was pervaded by a feeling that socialism would be permanent. Indeed, as early as 1944, the trustees of Castle Howard, convinced there was no future for Britain's great houses, had begun selling the house's contents.[7] Increasing taxes and a shortage of staff were already ensuring that the old way of life had gone for ever. The wealth and status of the owner provided no protection to the building as even the more wealthy owners became keen to free themselves of not only the expense of a large house, but also the trappings of wealth and redundant privilege, which the house represented. [8] Thus, it was not just the smaller country houses of the gentry which were wiped from their – often purposefully built – landscapes, but also the huge ducal palaces. Alfred Waterhouse's Gothic Eaton Hall, owned by Britain's wealthiest peer was razed to the ground in 1963, to be replaced by a smaller modern building. Sixteen years earlier the Duke of Bedford had reduced Woburn Abbey to half its original size, destroying façades and interiors by both Henry Flitcroft and Henry Holland. The Duke of Devonshire saved Hardwick Hall by surrendering it to the treasury in lieu of death duties, which were charged at the maximum rate of 80% of the total value of an estate,[9] but this solution was rarely acceptable to the government. As late as 1975, the British Labour government refused to save Mentmore, thus causing the dispersal, and emigration, of one of the country's finest art collections.

During the 1960s, historians and public bodies had begun to realise the loss to the nation of this destruction. However, the process of change was long, and it was not until 1984 with the salvation of Calke Abbey that it became obvious that opinion was truly changing, if not assured. A large public appeal assured the preservation of Tyntesfield in 2002, and as recently as 2007, Dumfries House and its collection were saved, but only after long and protracted appeals and debates. Although today demolition has ceased to be a realistic, or legal, option for listed buildings, and an historic house with its contents intact had become recognized as worthy of retention and preservation, often they are still at risk and their security, as an entirety, is not guaranteed by any legislation.

Nothing considered worthy of merit

For the majority of the 20th century, no house, regardless of its architectural or historic value, was safe from the risk of demolition. Houses ranging from those designed by such eminent architects as Robert Adam, to those designed by the competent, but lesser known and provincial, Bastard Brothers, were swept away with equal contempt. For a large part of the century, an owner merely had to formally notify his local authority of an intention to demolish, and then was free to raze the house to the ground. By and large, few were concerned at the loss to the nation's architectural heritage. The demolition was often a matter of public entertainment and spectacle, as the author, Robert Jefferey, describes of the demolition of Tong Castle, "... then, on 18th July 1954, a large crowd gathered to watch this historic event. The operation was conducted by the 213 Field Squadron Royal Engineers (T.A.). 208 boreholes were placed around the building, using 136 lbs of plastic explosive, and 75lbs of amatol. The Church windows were opened to cope with the blast. At 2.30 pm. Lord Newport fired the charges ... there are some fine photographs of this event, with the whole base of the Castle covered in smoke."[10]

Impoverished owners and a plethora of country houses

When Evelyn Waugh's novel Brideshead Revisited, portraying life in the English country house, was published in 1945, its first few chapters provided a glimpse into a privileged, exclusive and enviable world. A world of beautiful country houses with magnificent contents, privileged occupants, profuse servants and great wealth. Yet, in its final chapters, Brideshead's author accurately documented a changing and fading world. A world in which the country house as a symbol of power, privilege and a natural order, was not to exist.

As early as June 1940, while Britain was embroiled the early days of World War II, The Times, confident of a some day victory, instructed its readers "... a new order cannot be based on the preservation of privilege, whether the privilege be that of a county, a class, or an individual."[11] Thus it was after the end of the war, as the government handed back the requisitioned, and often dilapidated, mansions to owners facing problems of not just mounting taxation, but also a belief that the old order was passing, that so many felt able to abandon their ancestral piles. There were, and still are, few symbols more evocative of privilege than a landed estate. Thus, following the cessation of hostilities, the trickle of demolitions which had begun in the earlier part of the century, now became a torrent of destruction.

Destroying buildings of national or potential national importance was not an act peculiar to the 20th century in Britain. The demolition of Northumberland House, London, a prime example of the English Renaissance architecture, passed without significant comment the late 1860s. Town houses such as Northumberland house were highly visible displays of wealth and political power, so consequently more likely to be the victims of changing fashions.

The difference in the 20th century was that the acts of demolition were often acts of desperation and last resort; a house razed to the ground could not be valued for probate duty. A vacant site was attractive to property developers, who would pay a premium for an empty site that could be rebuilt upon and filled with numerous small houses and bungalows, which would return a quick profit. This was especially true in the years immediately following World War II, when Britain was desperate to replace the thousands of homes destroyed. Thus, in many cases, the demolition of the ancestral seat, strongly entwined with the family's history and identity, followed the earlier loss of the family's London house.

A significant factor, which explained the seeming ease with which a British aristocrat could dispose of his ancestral seat, was the aristocratic habit of only marrying within the aristocracy and whenever possible to a sole heiress. This meant that by the 20th century, many owners of country houses often owned several country mansions. Thus it became a favoured option to select the most conveniently sited (whether for privacy or sporting reason), easily managed, or of greatest sentimental value; fill it with the choicest art works from the other properties; and then demolish the less favoured. Thus, one solution not only solved any financial problems, but also removed an unwanted burden.

The vast majority of the houses demolished were of less architectural importance than the great Baroque, Palladian and Neoclassical mansions by the notable architects. These smaller, but often aesthetically pleasing houses belonged to the gentry rather the aristocracy; in these cases the owners, little more than gentlemen farmers, often razed the ancestral home to save costs and thankfully moved into a smaller but a more comfortable farmhouse, or purpose built new house on the estate.

Occasionally an aristocrat of the first rank did find himself in dire financial troubles. The severely impoverished Duke Of Marlborough saved Blenheim Palace by marrying an heiress, tempted from USA by the lure of an old title in return for vast riches.[12] Not all were so fortunate or seemingly eligible. When 2nd Duke of Buckingham found himself bankrupt in 1848, he sold the contents of Stowe House, one of Britain's grandest houses; this left his heirs, the 3rd and final Duke of Buckingham and his heirs the Earls Temple, with huge financial problems until finally in 1922 anything left that was moveable, both internal and external, was auctioned off and the house sold – narrowly escaping demolition. It was saved by being transformed into a school.[13] Less fortunate was Clumber Park, the principal home of the Dukes of Newcastle. Selling the Hope diamond and other properties failed to solve the family problems, leaving no alternative but the demolition of the huge, expensive-to-maintain house, which was razed to the ground in 1938, leaving the Duke without a ducal seat.[14] Plans to rebuild a smaller house on the site were never executed.[15] Other high ranking members of the peerage were also forced to off-load minor estates and seats; the Duke of Northumberland retained Alnwick Castle, but sold Stanwick Park to be demolished, leaving him with four other country seats remaining.[16] Likewise the Duke of Bedford kept Woburn Abbey while selling other family estates and houses. Whatever the personal choices and reasons for the sales and demolitions, the underlying and unifying factor was almost always financial. The root of the problem began long before the 20th century with the gradual introduction of taxes on inherited wealth.

Direct causes

Before the 19th century, the British upper classes enjoyed a life relatively free from taxation. Staff were plentiful and cheap, and estates not only provided a generous income from tenanted land but also political power. During the 19th century this began to change until by the mid 20th century they had no power and were suffering heavy taxation. The staff had either been killed in two world wars or forsaken a life of servitude for better wages elsewhere. Thus the owners of large country houses dependent on staff and a large income began by necessity to dispose of their material assets. Large houses had become redundant white elephants to be abandoned or demolished. It seemed that in particular regard to the country houses no one was prepared to lift a finger to save them.

There are several reasons which had brought about this situation - Most significantly in the early 20th century there was no legislation to protect what is now considered to be the nation's heritage. Additionally, public opinion did not have the sentiment and interest in national heritage that is evident in Britain today. When the loss of Britain's architectural heritage reached its zenith at the rate of one house every 5 days in 1955 few were particularly interested or bothered. In the immediate aftermath of World War II to the British public still suffering from the deprivations of food rationing and restriction on building work the destruction of these great redundant houses was of little interest, in fact to many they were seen as symbols of repression - places where their parents and grandparents had toiled in the basements for little reward. From 1914 onwards there had been a huge exodus away from a life in domestic service, having experienced the less restricted and better paid life away from the great estates few were anxious to return - this in itself was a further reason that life in the English country house was becoming near impossible to all but the very rich.

Another consideration was education, before the late 1950s and the advent of the stately home business very few working class people has seen the upstairs of these great houses, those that had were there only to only to clean and serve, with an obligation to keep their eyes down, rather than be educated or even to gawp. Thus ignorance of the Nation's heritage was a large contributory factor to the indifference that met the destruction. <Find a ref for all this look in GHQ Vol II and III>

All though cannot be blamed on public indifference successive legislation pertaining the national heritage, often formulated by the aristocracy themselves had deliberately omitted any references to private houses. The reasons that so many British country houses were destroyed in the 20th century can during the second half be fairly attributed to politics and social conditions. During the Second World War many large houses were requisitioned, and subsequently for the duration of the war were use for the billeting of military personnel, government operations, hospitals, schools and a myriad of other uses all far removed from the purpose for which they were designed. At the end of the war when handed back to the owners many were in a poor if not ruinous state of repair. During the next two decades restriction applied to building works as Britain was rebuilt, priority being given to replacing what had been lost during the war rather than the oversized home of a seemingly elite family. In addition death duties which had been raised to all time highs by the new Labour Government which swept into power in 1945 hit Britain's aristocracy hard. These factors coupled with a decrease in people available or willing to work as servants left the owners of country houses facing huge dilemmas of how to manage their estates. The most obvious solution was to off-load the the cash eating family mansion. Many were offered for sale suitable for institutional use, those not readily purchased were speedily demolished. In the years immediately after the war the law, even had it wished to, was powerless to stop the demolition of a private house no matter how architecturally important.

Loss of income from the estate

Before the 1870s, these estates often comprised of several thousand acres, generally consisting of a home farm, kitchen gardens (utilised to supply the mansion with meat, milk, fruit and vegetables), and several farms let to tenants. While such estates were sufficiently profitable to maintain the mansion and provide a partial - if not complete - income, the agricultural depression of the 1870s changed the viability of estates in general. Previously, such holdings yielded at least enough to fund loans on the large debts and mortgages usually undertaken to fund a lavish lifestyle;[19] often spent both in the country estate and in large houses in London.

By 1880, the agricultural depression lead some holders into financial shortfalls as they tried to balance maintenance of their estate with the income it provided. Some relied on funds from secondary sources such as banking and trade, or as in the case of the severely impoverished Duke Of Marlborough, married an heiress tempted from the US by the lure of an old title in return for vast riches.[20]

Loss of political power

The country houses have been described as "power houses" [21] from which their owners controlled not only these vast surrounding estates, but also, through political influence, the people living in the locality. Political elections held in public before 1872 gave suffrage to only a limited section of the community; many of whom were the landowner's friends, tradesmen with whom he dealt, or senior employees or tenants. The local landowner often not only owned an elector's house, but was also his employer, and it was not be prudent for the voter to be seen publically voting against his local candidate.

The Third Reform Act of 1885 widened the number of males eligible to vote to 60% of the population. Males paying an annual rental of £10, or holding land valued at £10 or over, were now eligible to vote. The other factor was the reorganization of constituency boundaries, thus a candidate who for years had been returned unopposed suddenly found part of his electorate was from an area outside of his influence. Thus the national power of the landed aristocrats and gentry was slowly diminished. The ruling class was slowly ceasing to rule. In 1888 the creation of local elected authorities eroded their immediate local power too. The final blow the reform of the house of Lords in 1911 proved to be the final factor of the beginning of the end for the country house lifestyle which had been enjoyed in a similar way for generations of the upper classes.

Land prices and incomes continued to fall, the great London palaces were the first casualties, the peer no longer needed to use his London house as a display of his might and power, its site was often more valuable empty than with the anachronistic palace in situ selling them was the for redevelopment was the obvious first choice to raise dome fast cash.[23] The second choice was sell part of the landed estate, especially if had been purchased in order to expand political territory. In fact, the buying of land, before the reforms of 1885, to expand political territory had earlier too had a detrimental effect on country houses. Often when a second estate was purchased to expand another, the purchased estate too had a country house. However, if the land (and its subsequent local influence) was the only requirement its house would then be let or neglected, often both. This was certainly the case at Tong Castle (see below) and many other houses. A large unwanted country house unsupported by land quickly becomes a liability.

Loss of wealth through taxation

Income tax

(this section can possibly be shortened and dispensed with)

Income tax was first introduced in Great Britain in 1799 as a means of subsidising wars defending against Napoleon [24] While not imposed in Ireland the rate of rate of 10% on the total income, with reductions only possible in incomes below £200 it immediately hit the better off. The tax was repealed for a brief period in 1802 during a cessation in hostilities with the French, but its reintroduction 1803 set the pattern for all future taxation in Britain.[25] While the tax was again repealed following the victory at Waterloo, the advantages of such taxation were now obvious. In 1841 following the election victory of Sir Robert Peel the exchequer was so depleted that the tax made surprise return on incomes above £150 while still known as a "temporary tax" [26] it was never again to be repealed. During the remainder of the century and the first decade of the 20th century all attempts to tax the rich harder were successfully fought (rephrase this) In 1907, Herbert Asquith introduced ‘differentiation’ a tax designed to be more punitive to those with investments rather than an earned income. This directly hit the aristocracy and gentry. Two years later Lloyd George in his People’s Budget of 1909 announced plans for a super-tax for the rich. The bill introducing the tax was defeated in the House of Lords. Any respite this defeat gave the owners of large country houses, many of them members of the House of Lords was to be brief and ultimately self-defeating. The bill's defeat led to the 1911 Parliament Act which removed the Lords’ power of veto. [27]

Death duties are the taxes most commonly associated with the decline of the British country house. These are, in fact, not a phenomenon in Britain peculiar to the 20th century, they had first been introduced 1796. Known as "Legacy Duty", it was a tax payable on money bequeathed from a personal estate. Next of kin inheriting were exempt from payment, but anyone other than wives and children of the deceased had to pay on a increasing scale depending on the distance of the relationship from the deceased.

The taxes gradually increased not only on the amount percentage of the estate that had to be paid, but also to include closer heirs liable to payment. By 1815 tax was liable to all except the spouse of the deceased.

By 1853 a new tax was introduced "Succession Duty" resulted in tax being liable on all forms of inheritance. In 1881 "Probate Duty" became liable on all personal property bequeathed at death. The wording personal property meant that for the first time not only the house and its estate were taxed but also the contents of the house and jewellery - these often were of greater value than the estate itself. By 1884 Estate Duty taxed property of any manner bequeathed at death.[28] but even when the Liberal government in 1894 reformed and tidied the complicated system at 8% on properties valued at over one million pounds they were not exorbitant. Death duties were though to slowly increase and become a serious problem to the country estate through out the first half of the 20th century reaching its zenith when assisting in the funding of of World War II. This proved to be the final straw for many families in 1940 death duties were raised from 50% to 65% following the cessation of hostilities they were raised a further twice between 1946 and 1949. Some families suffered a double blow, some estate owners had given their properties to their heirs in advance of their own deaths to escape duties, when subsequently the heir was killed fighting death duties became immediately payable, the estate would then pass back to the elderly former owner who in turn would die before the first death duties had been paid, in this way some estates were bankrupted. (is this true? - check it out)

Legislation to protect the national heritage

1882 and 1900 Ancient Monument and Amendment Acts

The Ancient Monument and Amendment Acts of 1882 was the first serious attempt in Britain to catalogue and preserve its ancient monuments. While the Acts failed to protect any country houses, a 1900 Act provided one important factor which saved many monuments of national importance. The 1900 Act made provision for owners of ancient monuments (on list of the 1882 catalogue) to enter into agreement with civil authorities whereby the property was placed under public guardianship. While these agreements did not divest the owner of the title to the property, they imposed on the civil authority an obligation to maintain and preserve for the nation.[29] So while the Acts may have been in favour of the owner, they set a precedent for the later preservation of structures of national importance. The main problem with the Acts was that, out of all Britain's great buildings, they only found 26 monuments in England, 22 in Scotland, 18 in Ireland and 3 in Wales worthy of preservation; all of which were prehistoric.[30]

While neolithic monuments were included the Acts specifically excluded inhabited residences. The prevailing philosophy was that an "Englishman's home is his castle" and the aristocratic ruling class of Britain inhabiting their homes and castles were certainly not going to be regulated by some lowly civil servants. This view was exemplified in 1911 when the immensely wealthy Duke of Sutherland acting in a whim wished to dispose of Trentham Hall, a vast Italianate palace in Staffordshire, he first offered it to the County Council, when no settlement could be reached he decided to demolish it. The small, but vocal, public resistance to this plan caused the Duke of Rutland to write an irate letter to The Times accusing the objectors of "impudence" and going to say "....fancy my not being allowed to make a necessary alteration to Haddon without first obtaining the leave of some inspector".[32][33] Thus despite money being no problem for its owner Trentham Hall was completely obliterated from its park, which the Duke retained and then opened to the public.[34] Thus it was that almost all country houses were left unprotected by any compulsory legislation.

The 1913 Ancient Monuments Consolidation Act was the first Act which had the aim of deliberately preserving as ancient monuments built since prehistoric times. Clearly defining a monument as: "Any structure or erection other than one in ecclesiastical use."[35] Furthermore, the Act compelled the owner of any monument on the list to notify the newly formed Ancient Monuments Board of any proposed alterations, including demolition. The Board then had the authority, if minded, to recommend that parliament place a preservation order on a building, regardless of the owner's wishes, and thus protect it.[36]

Like its predecessors, the 1913 Act deliberately omitted inclusion of inhabited buildings, whether they were castles or palaces, this was ironic as the catalyst for the 1913 Act had been the threat to Tattersall Castle, Lincolnshire.[37] An American millionaire wished to purchase the uninhabited castle, and ship it to the USA in its entirety. To frustrate the proposal, the castle had been purchased and restored by Lord Curzon and thus the export of Lord Cromwell's castle was prevented.[38] However, the 1913 Act was an important step in highlighting the risk to the nation's many historic buildings. The 1913 Act also went further than it predecessors by decreeing that the public should have access to the monuments preserved at its expense.

While the catalogue of buildings worthy of preservation was to grow, it remained narrow. and failed to prevent many of the early demolitions, including, in 1925, the export to the USA of the near ruinous Agecroft Hall. This fine half timbered example of Tudor domestic architecture, was shipped, complete with its timbers, wattle and daub, across the Atlantic.[39]

In 1931, the Ancient Monuments Consolidation Act was amended to restrict development in an area surrounding an ancient monument. The scope of buildings included was also widened to include: "Any building, structure or other work, above or below the surface".[40] However, the Act still excluded inhabited buildings. Had it done so, much of that destroyed before World War II could have been saved.

1932 Town and Country Planning Act

The 1932 Town and Country Planning Act was chiefly concerned with development and new planning regulations, however, amongst the small print was (Clause 17); this permitted a town council to prevent the demolition of any property within its jurisdiction. This clearly intruded into the "Englishman's home is his castle" philosophy, and provoked similar aristocratic fury to that seen in 1911. The Marquess of Hartington thundered: "(Clause 17) is an abominably bad clause, these buildings have been preserved to us by not by Acts of Parliament, but by the loving care of generations of free Englishmen who...did not know what a District Council was".[41] The Marquess, so against enforced preservation was, in fact, a member of the Royal Commission of Ancient and Historical Monuments, in the House of Lords.[42] The very body who oversaw the implementation of the (above) Acts intended to enforce preservation. Ironically, eighteen years later, on the untimely death of the marquess, by then Duke of Devonshire, his son was forced to surrender to the state, in lieu of death duties, one of England's most historic country houses, Hardwick Hall.

1944 Town and Country Planning Act

The 1944 Town and Country Planning Act, with the end of World War II in sight, was chiefly concerned with the redevelopment of bomb sites, but contained one crucial clause which concerned historic building, it charged local authorities to draw up a list of all buildings of architectural importance in its area, and most significantly, for the first time the catalogue was to include inhabited private residences.[43] This legislation created the foundations for what are today known as listed buildings scheme. Under the scheme, an interesting or historic building was graded according to it's value to the national heritage:

- Grade I (buildings are of exceptional interest)

- Grade II* (buildings of more than special interest)

- Grade II (buildings special interest, warranting every effort to preserve them) [44]

The Act criminalised unauthorised alterations, or demolitions, to a listed building, so in theory, at least all historic buildings were now safe, from unauthorised demolition. The truth was that the Act was rarely, enforced only a few buildings were listed, over half of them by just one council, Winchelsea.[45] Elsewhere, the fines levied on those failing to comply with the Act were far less than the profit from redeveloping a site. little changed. In 1946, in what has been described as an act of class warfare, the British Government insisted on the destruction, by open cast mining, of the park and gardens of Wentworth Woodhouse, Britain's largest country house, a cabinet minister insisting, as 300 year old oaks were uprooted, that "the park be mined right up to the door."[46]

1947 Town and Country Planning Act

The apathy towards the nation heritage continued after the passing of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, despite the fact, this was the most comprehensive law pertaining to planning legislation in England. The 1947 Act went further than its predecessors in dealing with historic buildings, as it required owners of property to notify their local authority of intended alterations, and more significantly, demolitions. This caught any property which may have escaped official notice previously. Theoretically, it gave the local authority the opportunity to impose a preservation order on the property and prevent demolition. Under this law the Duke of Bedford was fined for demolishing half of Woburn Abbey without notification, although it is inconceivable that the Duke would have been able to demolish half of the huge house (much of it visible from a public highway) without attracting public attention until the demolition was compete.

The apathy and disinterest of local authorities and the public resulted in poor enforcement of the Act, and revealed the true root of the problem. When in 1956 Lord Lansdowne notified the "Ministry of Housing and Government" of his intention to demolish the greater part and corps de logis of Bowood designed by Robert Adam, with the exception of James Lees-Milne, the noted biographer and historian of the English country house) no preservation society of historical group raised an objection and the demolition went ahead unchallenged. The mid 1950s, which should have been regulated by the above Acts, was the era in which most houses were legitimately destroyed, at an estimated rate of one every five days. [47]

1968 Town and County Planning Act

The demolition finally began to noticeably slow following the passing of 1968 Town and County Planning Act. This Act compelled owners to seek and wait for permission to demolish a building, rather than merely notify the local authority. It also gave the local authority powers to list a building overnight. Thus it was that 1968 became the last year when demolition ran into double figures.[48] Perhaps, not coincidentally, in the weeks immediately preceding ratification of the Act, there were a spate of sudden and unexplained fires destroying dozens of country houses.[49]

The final and perhaps most important factor which secure Britain's heritage was a change in public opinion. This was largely brought about by the Destruction of the Country House Exhibition held at London's Victoria and Albert Museum in 1974. The public's response to this highly publicised exhibition was unprecedented.[50], it was as though the general public of Britain had been completely unaware of the catastrophe taking place around them.

Today, over 370,000 buildings are listed, this includes all buildings erected before 1700 and most constructed before 1840, after that date a building has to be of architectural or historical importance to be protected.[51]

Re-evaluation of the country house

The unprecedented demolitions of the 20th century did not however see the complete demise of the country house, but a consolidation of those that were most favoured by their owners. Many were the subject of vast alteration and rearrangements of the interior, to facilitate the new way of life less dependant on vast armies of servants. large service wing often later 19th century additions were often demolished, as at Sandringham House, or allowed to crumble as was the case at West Wycombe Park where the service wing was unreliably attributed to Robert Adam.

The stately home business

Many of Britain's greatest houses had frequently been open to the paying paying public. In the early 19th century, Jane Austen records such trip in her novels. Well heeled visitors could knock on the front door and a senior servant would give a guided tour for a small renumeration. Later in the century, on days when Belvoir Castle was open to the public the 7th Duke of Rutland was reported by his granddaughter, the socialite Lady Diana, to assume a "look of pleasure and welcome."[52] Here and elsewhere, however, that welcome did not extend to a tea room and certainly not to chimpanzees swinging through the shrubbery, that was all to come over 50 years later. At this time, admittance was granted in patrician fashion with all proceed usually donated to a local charity.[53]

Following World War II, many owners of vast houses faced an dilemma, often they had already disposed of minor country to preserve the principal seat, now that seat too was in jeopardy. The principal house was more than just a dwelling; built when the family was at the height of its power, wealth and glory, it represented the family's history and status it was an integral part of the family's being and needed to be preserved, even if this meant "entering trade", a prospect which would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier.

[[:File:SAVEMentmore.jpg|thumb|right|200px|SAVE's campaign to save Mentmore Towers in 1974, was unsuccessful, the priceless contents were sold, and now dispersed over the word, and the house sold and allowed to decay. Today, 36 years after it ceased to be a private house, it lies empty, "at risk" and facing an uncertain future.]]

This is can be exemplified by the business ventures executed by the Marquess of Bath at Longleat House. Reacquiring occupation of this enormous 16th century mansion, in a state of poor repair, following requisition during World War II, the marquess was faced with death duties of £700,000, the marquess through the house open to the paying public and kept the proceeds himself to fund the mansion. In 1966, to keep attendance numbers high, the peer went a step further and introduced lions to the park, thus creating Britain's' first safari park. After the initial opening of Longleat, the Dukes of Marlborough, Devonshire and Bedford threw open the doors of Blenheim Palace, Chatsworth House and what remained of Woburn Abbey. With the example and precedent of "trade" set by those at the top of the aristocratic pyramid, within a few years hundreds of Britain's country houses were open two or three days a week to public eager to see the rooms which a few years earlier their ancestors had cleaned. By 1992, 600 "stately homes" were visited annually by 50 million members of the paying public.[54] Stately homes were now big business, but opening a few rooms and novelties in the park alone were not going to fund the houses beyond the final decades of the twentieth century. Even during the stately home boom years of the 1960s and 1970s historic houses were still having their contents sold, being demolished or if permission to demolish was not forthcoming being left to dereliction and ruin.

By the early 1970s the demolition of great country houses began to slow. However while the disappearance of the houses eased the dispersal of the contents of many of these near redundant museums of social history did not, a fact highlighted in the early 1970s by the dispersal sale of Mentmore. The eminent architectural historian and President of SAVE Britain's Heritage, Marcus Binney's high profile campaign to save the mid Victorian mansion failed; and the subsequent departure from Britain of many important works of art from Mentmore caused public opinion to slowly change. The house had in fact been offered to the nation by its owners in lieu of death duties, but the Labour Government of James Callaghan with a general election in sight did not wish to be seen saving the ancestral home of an hereditary nobleman and thus rejected the offer. However, that same year the destruction finally came to a near standstill. This was not just due to stricter application of legislation, but also in part due to the high profile Destruction of the Country House exhibition held by the Victoria and Albert Museum. However, the damage to the nation's heritage had been done.

The future

By 1984 public and Government opinion has so changed that a campaign to save the semi-derelict, but untouched by time, Calke Abbey was successful. Writing in 1992, 47 years after his father wrote his melancholy novel prophesying the decline of county house life, Auberon Waugh, writing in the Daily Telegraph, felt confident enough of the survival of the country house as a domestic residence to declared: "I would be surprised if there is any greater happiness than that provided by a game of croquet played on an English lawn through a summer's afternoon, after a good luncheon and with the prospect of a good dinner ahead. There are not that many things which the English do better than anyone else. It is encouraging to think we are still holding on to a few of them."[55]

Waugh was writing of the survival of Brympton d'Evercy which in the preceding 50 years had been transformed from am ancestral home and hub of an estate, to a school, then following a brief period while its owners tried to save it as stately home open to the public it had been sold purchased for use as a private residence once again, albeit also doubling as a wedding venue and sometime filmset; both common a lucrative sources of country house income in the 21t century. The 21st century has also seen many country houses transformed into into places of seemingly antiquated luxury, in order to meet that new British phenomena, the county house hotel, this has been the fate of Luton Hoo and Hartwell House.

Occasionally, a country houses have been saved for purely public appreciation as a the result of public appeals and campaigns, such as Tyntesfield, a Victorian Gothic Revival mansion in North Somerset, which was saved as an entirety with its contents in 2002. In 2007, after a prolonged and controversial appeal Dumfries House, an important Scottish country house complete with its original Chippendale furnishings was save for the nation following direct intervention and funding from the Prince of Wales; its contents had already been catalogued by Sotheby's for auction. The controversy and debate concerning the salvation echoed the debates of the early 20th century concerning the worth to the national heritage. Today, the British country house is safe from demolition, but its worth is still subject to debate and re-evaluation.

Notes

- ^ Clay, p 56

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/3578853/Country-houses-the-lost-legacy.html

- ^ Binney

- ^ Gow

- ^ RCAHMS.

- ^ V&A.[1]

- ^ Worsley, p 95

- ^ Mulvagh, p321

- ^ Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire, p 60.

- ^ Jeffery, chapter 5

- ^ Mulvagh, p 321.

- ^ Stuart, p. 135

- ^ The history of Stowe

- ^ Much later during the the 1950s, the 9th Duke moved to Wiltshire making Boyton, a former Fane estate, the family's principal home.

- ^ Biography of Henry Francis Hope Pelham-Clinton-Hope

- ^ Worsley, p.9

- ^ Worsley,p 21

- ^ Both Holden and Broxtowe make this claim

- ^ Worsley p 11

- ^ Stuart, p. 135

- ^ Girouard find the page number

- ^ Jeffery, chapter 5

- ^ Worsley p 12

- ^ [2]

- ^ H M Revenue and Customs

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ Facts in this section from "Find My Past"

- ^ Outer House, Court of Session (A1497/02) retrieved 08 July 2008

- ^ Mynors, p 8.

- ^ Scotland on Sunday

- ^ Worsley, p 9

- ^ In fairness to the Duke of Rutland, it should be pointed out that his restoration work at Haddon Hall had saved the medieval mansion from ruin.

- ^ Worsley

- ^ Mynors, p 9.

- ^ Mynors, p 9.

- ^ Worlsey, p 9.

- ^ Worlsey, p 9

- ^ Agescroft Hall, Richmond, Virginia. Retrieved 09 July 2008

- ^ Mynors, p 10.

- ^ Mynors, p 11

- ^ Mynors, p 10

- ^ Worsley, p.17

- ^ British Heritage

- ^ Mynors, p 11

- ^ .Find a ref for this:probably in Black Diamonds

- ^ need a ref for this

- ^ Worley, p23

- ^ Worsley find where

- ^ JD find the page last couple of pages

- ^ English Heritage

- ^ Vickers, Rutland obituary.

- ^ Deborah Devonshire in "Wait for me" records that before the 1950s all monies gained from admittance to Chatsworth were donated to a local hospital.Find page.

- ^ Vickers, obituary

- ^ Auberon Waugh. The Daily Telegraph. P17. 31 August 1992

References

- Binney, Marcus (2006). Lost Houses of Scotland. Save Britain's Heritage. ISBN 0-905978-05-6.

- Clay, Catrine (2006). King, Kaiser, Tsar. London: John Murray. ISBN 13-978-0-7195-6536-7.

- Devonshire, Deborah, Duchess of. Chatsworth. Derbyshire Countryside Ltd. ISBN 085100 118 1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gow, Ian (2006). Scotland's Lost Houses. Trafalgar Square. ISBN 1845130510.

- Jeffery, Robert (2007). Discovering Tong, Its History, Myths and Curiosities. Privatly Published. ISBN-13 978-0-9555089-0-5.

- King, David (2001). The Complete Works of Robert and James Adam. Architectural Press. ISBN 0750644680.

- Moore, Victor (2005). A Practical Approach to Planning Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0 19 927299 4.

- Mulvagh, Jane (2006). Madresfield, The Real Brideshead. London: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385607728.

- Mynors, Charles (2006). Listed Buildings, Conservation Areas and Monuments. London: Sweet & Maxwell. ISBN 0421758309.

- Worsley, Giles (2002). England's lost Houses. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1 85410 820 4.

- Vickers, Hugo (1 July 1992). Obituary of the Marquess of Bath. London: The Independent. [5] retrieved 1 December 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link)

- Find my past retrieved 22 march 2007

- St Louis Art Museumretrieved 22 march 2007

- Broxtow Borough retrieved 23 March 2007

- Nuthall Temple by Mrs Holden retrieved 23 March 2007

- Wolverhampton's Listed Buildings retrieved 23 March 2007

- BBC.CO.UK retrieved 23 March 2007

- British History Online retrieved 25 March 2007

- The Marjoribanks Journal retrieved 25 March 2007

- Scotland in Sunday, Sun 5 Nov 2006 retrieved 25 March 2007

- Independence of Ireland retrieved 25 March 2007

- Stuart, Amanda Mackenzie, Consuelo and Alva Vanderbilt: The Story of a Daughter and Mother in the Gilded Age, Harper Perennial, 2005, ISBN 978-0-06-093825-3

- The history of Stowe retrieved 09 October 2007

- Biography of Henry Francis Hope Pelham-Clinton-Hope, 8th Duke (1866-1941) retrieved 10. October 2007

- RCHAMS retrieved 17 March 2007

- English Heritage retrieved 10 July 2008

External links

Scotland's lost houses retrieved 11 July 2008 [

PAGE ENDS HERE

Useful memo things for me

- Exhibitions at the V&A

- "The Destruction of the Country House", 1974

- "SAVE Britain’s Heritage 1975-2005: 30 Years of Campaigning", 3 November 2005 – 12 February 2006 [6]

- Garendon Hall which was demolished in 1964

Description from here of the explosion of a house: [8]

- Charles Boot Interesting page, bring him and people like him in on Clumber etc. and Thornbridge Hall.

- Harewood Park demolished 1959 [9] [10]

- Castle Howard gutted by fire November 1940 - now partially restored

- Agecroft Hall transported to USA and rebuilt in Richmond [11]

- Calke Abbey use facts from here.

Ended in late 1960s/early 1970s by Town and Country Planning Act 1968 and change of attitudes.

Mention Halnaby Hall demolished 1952 - attempts to save ut etc *Byron's honeymoon

Mynors online [12]