Pasty: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

*[http://www.kenanderson.net/pasties/ Recipes, and history of the pasty in "Pasties, Plain and Simple" by Ken Anderson] |

*[http://www.kenanderson.net/pasties/ Recipes, and history of the pasty in "Pasties, Plain and Simple" by Ken Anderson] |

||

*[http://www.greenchronicle.com/connies_cornish_kitchen/cornish_pasty.htm Comprehensive recipe for an authentic Cornish pasty including pictures showing the process.] |

*[http://www.greenchronicle.com/connies_cornish_kitchen/cornish_pasty.htm Comprehensive recipe for an authentic Cornish pasty including pictures showing the process.] |

||

*[http://www.thepasty.com The Pasty.com] Information about pasties and online shop. |

|||

*[http://www.cornwalls.co.uk/food/pasty.htm The Cornish Pasty] History, varieties and recipe |

*[http://www.cornwalls.co.uk/food/pasty.htm The Cornish Pasty] History, varieties and recipe |

||

Revision as of 21:23, 1 September 2006

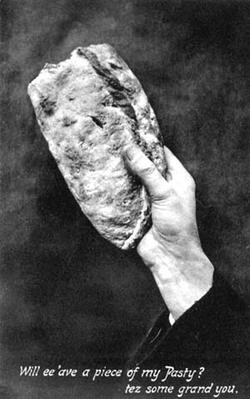

A pasty (Cornish: Pasti, Hoggan, incorrectly written as pastie) is a type of pie, originally from Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is a baked un-sweetened pastry case traditionally filled with diced meat and vegetables. The ingredients are uncooked before being placed in the unbaked pastry case.[1] Pasties with traditional ingredients are specifically named Cornish pasties. Traditionally, pasties have a semicircular shape, achieved by folding a circular pastry sheet over the filling. One edge is crimped to form a seal.

The consonant 'a' in pasty is 'pure' (IPA /ˈpæsti/, /ˈpɑːsti/). Thus, "pasty" does not sound anything like "paste." The exact pronunciation varies among dialects.

Oggy is a slang term used in Britain which comes from a Cornish term for the pasty. The food is extremely popular in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where it has become an icon of the region, introduced through the wave of European immigrants to the United States.

Ingredients

While there are no completely standard pasty ingredients, almost every traditional recipe includes diced skirt steak, finely sliced onion, and potato. Other common ingredients include swede (rutabaga) (called turnip in Cornwall) and possibly parsley. The presence of carrot in a store-bought pasty is usually an indication of inferior quality. Other cuts of beef are occasionally used instead of skirt, and steak can also be replaced by beef mince (ground beef), although in Cornwall this is also a sign of inferior quality. While it is a common ingredient, meat was a luxury for many 19th century Cornish miners, so traditional pasties can include many more vegetables than meat.

Pasty ingredients are usually seasoned with salt and pepper, depending on individual taste.[2] There is anecdotal evidence for a "two course" pasty, which has meat and vegetables at one end, and fruit (such as apples, plums, or cherries) at the other.[2] This would reflect the pasty's use as a complete meal for miners, but it is disputed whether the fruit ingredients could actually survive the lengthy baking process required for the meat. No such "two course" pasty is commercially produced in Cornwall today.[3]. However 'pork and apple' pasties are readily available in shops throughout Cornwall, albeit with the ingredients, including an apple flavoured sauce, mixed together throughout the pasty.[1]

Today, pasty contents vary, especially outside of Cornwall. Common fillings include beef steak and stilton, chicken and ham, cheese and vegetable and even turkey and stuffing. Other specialty pasties include breakfast and vegetarian pasties. Pasty crust recipes also vary. Traditional recipes call for a tough (not flaky) crust, which could withstand being held and bumped in the Cornish tin mines. Modern pasties almost always use a short (or pastry) crust.[2] There is a great deal of debate among pasty makers about the proper traditional ingredients and recipes for a pasty, specifically the mixture of vegetables and crimping of the crust.[1] The crimping debate is contested even in Cornwall itself, with some advocating a side crimp while others maintain that a top crimp is more authentic.[3] Another theory is that a pasty whose crimp is at the top of the crust rather than the side is more common in Devon.[2]

In Cornwall there is also a version known as the windy pasty. This is made by taking the last bit of pastry left over from making pasties, which is then rolled into a round, folded over and crimped as for an ordinary pasty. It is baked in an oven and when done (while still hot) opened out flat and filled with jam. It may be eaten hot or cold. [2]

Pasties were traditionally eaten as a complete meal, with the vegetable and meat juices acting as a form of gravy. Nowadays, pasties are sometimes served with gravy or ketchup as a dressing.

History

The origins of the pasty are largely unknown. It has been conjectured that the pasty originated in Cornwall. In the 1800s, pasties had evolved to meet the needs of Cornish tin miners, as tin mining was a major Cornish industry at the time. Tradition claims that the pasty was originally made as lunch ('croust' in the Cornish language) for Cornish miners who were unable to return to the surface to eat. The story goes that, covered in dirt from head to foot (including some arsenic often found with tin), they could hold the pasty by the folded crust and eat the rest of the pasty without touching it, discarding the dirty pastry. The pastry they threw away was supposed to appease the knockers, capricious spirits in the mines who might otherwise lead miners into danger.[1] A related tradition holds that it is bad luck for fishermen to take pasties to sea.

The pasty's dense, folded pastry could stay warm for 8 to 10 hours and, when carried close to the body, helped the miner stay warm.[4] In such pasties meat and each vegetable would each have its own pastry "compartment," separated by a pastry partition. Traditional bakers in former mining towns will still bake pasties with fillings to order, marking the customer's initials with raised pastry. This practice was started because the miners used to eat part of their pasty for breakfast and leave the remaining half for lunch, meaning that a way to identify the pasties was needed.[5] Some mines kept large ovens to keep the pasties warm until mealtime. It is said that a good pasty should be strong enough to endure being dropped down a mine shaft.[6]

Pasties are still very popular throughout Devon and Cornwall, and also in the rest of the United Kingdom. Pasties in these areas are usually hand-made and sold in bakeries or (less often) specialist pasty shops. They are also sold in supermarkets, but these are mass produced and often taste entirely different from traditional Cornish pasties. Several pasty shop chains have also opened up in recent years, selling pasties that are more traditional than the common mass-produced varieties while still offering novel fillings. It is common in some areas for pasties to be eaten "on-the-move" from the paper bag they are sold in, making them essentially a fast food.

Cornish miner immigrants helped to spread pasties into the rest of the world, in the 19th century. As tin mining in Cornwall began to fail, miners brought their expertise and traditions to new mining regions. As a result, pasties are very common in Nevada County, California; Silver Bow County, Montana and Deer Lodge County, Montana; parts of Wisconsin; and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. In these areas, pasties are now a major tourist draw, including an annual Pasty Fest in early July in Calumet, Michigan. Pasties in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan have a particularly unusual history, as a small influx of Finnish immigrants followed the Cornish miners, in 1864. These Finns (and many other ethnic groups) adopted the pasty for use in the Copper Country copper mines. About 30 years later, a much larger flood of Finnish immigrants found their countrymen baking pasties, and assumed that it was a Finnish invention. As a result, the pasty has become strongly associated with Finnish culture in this area.[4]

Pasties are also found in the slate mining region of eastern Pennsylvania, where settlers from Cornwall and parts of Wales also were fond of the pasty and used them consistently as a food source for men working in slate quarries in the "Slate Belt" region that included the towns of Bangor, East Bangor, Pen Argyl and Wind Gap, Pennsylvania. Many churches to this day hold "pastie suppers" or sell the items as a means of making money for their parishes.

Pasties are also found in South Australia (particularly the Yorke Peninsula). Most country bakeries in South Australia produce pasties, as well as large brandnames such as Balfour's and Vili's. They may also be found in the Mexican cities of Pachuca and Real del Monte, and are commonly served with different ingredients, such as jalapeño peppers.

In 1985 a group of Young Farmers in Cornwall spent 7 hours making a record-breaking pasty - over 32ft long. This was believed to have been beaten in 1999 when bakers in Falmouth made their own giant pasty during the town's first ever pasty festival.[1]

Cultural references

In the 2006 short film Shanks, actor Jackoby Flash ate his way through six Cornish Pasties in the space of half of an hour, just to achieve roughly thirty seconds of useable footage.

A traditional Cornish tale claims that the devil knew of Cornishwomen's propensity for putting any available food into pasties, and would never dare to cross the River Tamar into Cornwall for fear of ending up as a pasty filling.[5]

The earliest known literary reference to pasties appears in an Arthurian romance by Chretien de Troyes from the 1100's, set in Cornwall and written for the Countess of Champagne. This work includes the line: "Next Guivret opened a chest and took out two pasties. 'My friend,' said he, 'Now try a little of these cold pasties ...' "[4] References to pasties later occur in various Robin Hood stories of the 1300's.[4]

There are references to pasties in three of Shakespeare's plays. In The Merry Wives of Windsor, Act 1 Scene 1 the Page says "Wife, bid these gentlemen welcome. Come, we have a hot venison pasty to dinner: come gentlemen, I hope we shall drink down all unkindness". In All's Well That Ends Well, Act IV Scene III, Parrolles states: "I will confess to what I know without constraint: if ye pinch me like a pasty, I can say no more". Finally, in Titus Andronicus, Titus bakes Chiron and Demetrius's bodies into a pasty, and forces their mother to eat them.

In the novel American Gods by Neil Gaiman, main character Shadow Moon discovers pastys at Mabel's restaurant in the fictional town of Lakeside. The food is mentioned as being popularized in America by Cornish men, similar to how gods are "brought over" to America in the rest of the story.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Christopher Lean. "The Cornish Pasty". Retrieved 2006-3-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d Ann Pringle Harris (1988-2-7). "Fare of the Country; In Cornwall, a Meal in a Crust". New York Times. Retrieved 2005-3-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Hettie Merrick. The Pasty Book. Tor Mark Press, Penryn, 1995.

- ^ a b c d Luke Miller and Marc Westergren. "History of the Pasty". The Cultural Context of the Pasty. Retrieved 2006-3-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Edith Martin. Cornish Recipes: Ancient and Modern. A. W. Jordan.

- ^ Horace Sutton (1972-10-1). "Cornwall: Land of King Arthur". Chicago Tribune.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

External links

- History of the Pasty: "The easiest way to describe a pasty, is a pot pie without the pot..."

- Pasties in Michigan's Upper Peninsula: Foodways, Interethnic Relations, and Regionalism, by Yvonne R. Lockwood and William Lockwood

- Pasties in Wisconsin, by Dorothy Hodgson

- Detailed recipe for making Cornish Pasty

- Recipes, and history of the pasty in "Pasties, Plain and Simple" by Ken Anderson

- Comprehensive recipe for an authentic Cornish pasty including pictures showing the process.

- The Pasty.com Information about pasties and online shop.

- The Cornish Pasty History, varieties and recipe