Bushwhacker: Difference between revisions

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

* The game ''[[Red Dead Redemption 2]]'' features a gang known as the Lemoyne Raiders, who operate as [[American_Civil_War|post-war]] pro-Confederate bushwhackers seemingly influenced by the Quantrill Raiders. |

* The game ''[[Red Dead Redemption 2]]'' features a gang known as the Lemoyne Raiders, who operate as [[American_Civil_War|post-war]] pro-Confederate bushwhackers seemingly influenced by the Quantrill Raiders. |

||

* [[The Bushwhackers]], a wrestling tag team from New Zealand were part of the [[WWE|World Wrestling Federation]] from 1988 to 1996. |

* [[The Bushwhackers]], a wrestling tag team from New Zealand were part of the [[WWE|World Wrestling Federation]] from 1988 to 1996. |

||

* |

* Bushwhackers or 'bushwackers' appear as a type of bandit npc in different games. |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 19:58, 7 July 2021

Bushwhacking was a form of guerrilla warfare common during the American Revolutionary War, War of 1812, American Civil War and other conflicts in which there were large areas of contested land and few governmental resources to control these tracts. This was particularly prevalent in rural areas during the Civil War where there were sharp divisions between those favoring the Union and Confederacy in the conflict. The perpetrators of the attacks were called bushwhackers. The term "bushwhacking" is still in use today to describe ambushes done with the aim of attrition.[1]

Bushwhackers were generally part of the irregular military forces on both sides. While bushwhackers conducted well-organized raids against the military, the most dire of the attacks involved ambushes of individuals and house raids in rural areas. In the countryside, the actions were particularly inflammatory since they frequently amounted to fighting between neighbors, often to settle personal accounts. Since the attackers were non-uniformed, the government response was complicated by trying to decide whether they were legitimate military attacks or criminal, terrorist actions.

Union Jayhawkers and Confederate bushwhackers

The term "bushwhacker" came into wide use during the American Civil War (1861-1865).[2] It became particularly associated with the pro-Confederate secessionist guerrillas of Missouri, where such warfare was most intense. Guerrilla warfare also wracked Kentucky, Tennessee, northern Georgia, Arkansas, and western Virginia (including the new state of West Virginia), among other locations.[3][4][5]

In some areas, particularly the Appalachian regions of Tennessee and North Carolina, the term bushwhackers was used for Confederate partisans who attacked Union forces.[6][7] Residents of southern Alabama used the name in the same manner.[8] Several bushwhacker bands operated in California in 1864.[9]

Pro-Union guerrilla fighters in Kansas were called "Jayhawkers".[10] They were involved in cross-border raids into Missouri.

Partisan rangers

In most areas, irregular warfare operated as an adjunct to conventional military operations. The title adopted by the Confederate government in formally authorizing such insurgents was "partisan ranger". One of them was Col. John Singleton Mosby, who carried out raids on Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley and northern Virginia. He also raided to the north in Kentucky and Tennessee. Partisan rangers were also authorized in Arkansas.[11][12]

In Missouri, however, secessionist bushwhackers operated outside of the Confederate chain of command. On occasion, a prominent bushwhacker commander might receive formal Confederate rank, as in the case of William Clarke Quantrill.[13] Or they might receive written orders from a Confederate general, as "Bloody Bill" Anderson did in October 1864 during a large-scale Confederate incursion into Missouri,[14] or as when Joseph C. Porter was authorized by Gen. Sterling Price to recruit in northeast Missouri. Missouri guerrillas frequently assisted Confederate recruiters in Union-held territory. For the most part, however, Missouri's bushwhacker squads were self-organized groups of young men, predominantly from the slave-holding counties along the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. They independently organized and fought against Federal forces and their Unionist neighbors, both in Kansas and Missouri. Their actions were in retaliation for what they considered a Federal invasion of their home state.[15]

Atrocities

The conflict with Confederate bushwhackers rapidly escalated into a succession of atrocities committed in Missouri by both sides. Hostage-taking and banishment were employed by local District and Union commanders to punish secessionist sympathizers.[16] Individual families, including that of Jesse and Frank James and the maternal grandparents and mother of future President Harry Truman, were banished from Missouri.

Union troops often executed or tortured suspects without trial and burned the homes of guerrillas and those suspected of aiding or harboring them. If official credentials were doubted, the suspects were often executed, as in the case of Lt. Col. Frisby McCullough after the Battle of Kirksville. Bushwhackers retaliated by ambushing federal soldiers and frequently going house to house and executing Unionist sympathizers.[17]

One of the most vicious actions during the Civil War by the bushwhackers was the Lawrence Massacre. William Quantrill led a raid in August 1863 on Lawrence, Kansas, burning the town and murdering some 150 men and boys in Lawrence.[18][19] Bushwhackers justified the raid as retaliation for the Sacking of Osceola, Missouri two years earlier, in which the town was set aflame and at least nine men killed, and for the deaths of five female relatives of bushwhackers killed in the collapse of a Kansas City, Missouri jail.[20][21]

To end guerrilla raids into Kansas, the Union commander of the District of the Border, which comprised counties along the Missouri-Kansas state line,[23] Thomas Ewing, Jr. ordered the total depopulation of Jackson, Cass, Bates, and northern Vernon counties in Missouri under his General Order No. 11.[24][25] Near 25 thousand rural inhabitants had to go to areas near Union camps or leave the state; their houses were burned to prevent them from returning; altogether, twenty-two hundred square miles of western Missouri became a desolation by the end of September 1863.[26][27] A minister, George Miller, who lived in Kansas City, wrote, "For miles and miles we saw nothing but lone chimneys. It seemed like a vast cemetery — not a living thing to break the silence." The District of the Border became known as the "burnt district."[28]

The Missouri-Arkansas border had been desolated as well. The Little Rock Arkansas Gazette wrote in August 1866:

Wasted farms, deserted cabins, lone chimneys marking the sites where dwellings have been destroyed by fire, and yards, gardens and fields overgrown with weeds and bushes are everywhere within view. The traveler soon ceases to wonder when he sees the charred remains of burnt buildings, and wonders rather when he beholds a house yet standing that it also did not disappear in the general conflagration. Such was the terrible intensity of the recent civil war ... .[29]

In other areas of Missouri, properties were also pillaged and destroyed by both warring sides since atrocities during the Civil War were in many ways a continuation of Bleeding Kansas violence.[30]

Centralia Massacre

Besides the attack on Lawrence, the most notorious atrocity by Confederate bushwhackers was the murder of 24 unarmed Union soldiers pulled from a train in the Centralia Massacre in retaliation for the earlier execution of a number of Anderson's own men. In an ambush of pursuing Union forces shortly thereafter, the bushwhackers killed well over 100 Federal troops.[31] In October 1864, "Bloody Bill" Anderson was tricked into an ambush and killed by state militiamen under the command of Col. Samuel P. Cox. Anderson's body was displayed following his death.[32]

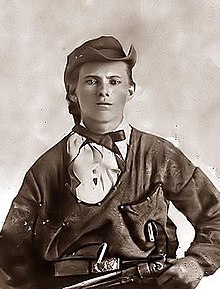

Jesse James

The guerrilla conflict in Missouri was, in many respects, a civil war within the Civil War.[33] Jesse James began to fight as an insurgent in 1864. During months of often intense combat, he battled only fellow Missourians, ranging from Missouri regiments of U.S. Volunteer troops, to state militia, to unarmed Unionist civilians. The single confirmed instance of his exchanging fire with Federal troops from another state occurred a month after the 1865 surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, during a near-fatal encounter with Wisconsin cavalrymen. In the course of the war, James' mother and sister were arrested, his stepfather tortured, and his family banished temporarily from Missouri by state militiamen— all Unionist Missourians.[34][35]

Postwar banditry

After the end of the war, the survivors of Anderson's band (including the James brothers) remained together under the leadership of Archie Clement, one of Anderson's lieutenants. In February 1866, they began a series of armed robberies. This group became known as the James-Younger Gang, after the death or capture of the older outlaws (including Clement) and the addition of former bushwhacker Cole Younger and his brothers. In December 1869, Jesse James became the most famous of this group when he emerged as the prime suspect in the robbery of the Daviess County Savings Association in Gallatin, Missouri, and the murder of cashier John W. Sheets.[36] During Jesse James's flight from the scene, he declared that he had killed Samuel P. Cox and had taken revenge for Bloody Bill Anderson's death. (Cox lived in Gallatin, and the killer apparently mistook Sheets for the former militia officer.) Throughout James' criminal career, he often wrote to the newspapers portraying himself as a bushwhacker, and rallying the support of former Confederates and other Missourians who were harmed by Federal authorities during the Civil War and Reconstruction.[37]

After the end of the war in 1865, the Mason Henry Gang continued as outlaws in Southern California with a price on their heads for the November 1864 "Copperhead Murders" in the San Joaquin Valley of three men they believed to be Republicans. Tom McCauley, known as 'James' or 'Jim Henry,' was killed in a shootout with a posse from San Bernardino on September 14 of that year, in San Jacinto Canyon, in what was then San Diego County. John Mason was killed by a fellow gang member for the reward in April 1866 near Fort Tejon in Kern County.

In 1867, near Nevada, Missouri, a band of bushwhackers shot and killed Sheriff Joseph Bailey, a former Union brigadier general, who was attempting to arrest them. Among those suspected of his killing was William McWaters, who once rode with Anderson and Quantrill.[38]

In popular culture

- Bushwhackers are the primary focus of the 1999 film “Ride With the Devil”.

- The bushwhackers are a major focus of Wildwood Boys (2000), a biographical novel of "Bloody Bill" Anderson by James Carlos Blake.

- The films The Outlaw Josey Wales and Ride with the Devil are both about bushwhackers.

- Bushwhackers appear in the side-stories of the HBO series Deadwood, set in South Dakota.

- The game Red Dead Redemption 2 features a gang known as the Lemoyne Raiders, who operate as post-war pro-Confederate bushwhackers seemingly influenced by the Quantrill Raiders.

- The Bushwhackers, a wrestling tag team from New Zealand were part of the World Wrestling Federation from 1988 to 1996.

- Bushwhackers or 'bushwackers' appear as a type of bandit npc in different games.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Oxford Dictionary

- ^ Ingenthron, Charles Elmo. Civil War: Guerillas, Jayhawkers, Bushwackers, White River Valley Historical Quarterly, Volume 2, Number 4 - Summer 1965

- ^ Life of a Guerilla in Missouri, The Missouri History Museum

- ^ Missouri Bushwhackers – Attacks Upon Kansas, Legends of America

- ^ Bushwhacking - a system of warfare and execution, The Fort Scott Tribune, June 21, 2008

- ^ Trotter, William R. Bushwhackers! The Civil War in North Carolina: Vol. II The Mountains. Greensboro, NC: Signal Research, Inc., 1988.

- ^ Inscoe, John C. & Gordon B. McKinney. The Heart of Confederate Appalachia: Western North Carolina in the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- ^ Kelly Kazek, and Wil Elrick. Alabama Scoundrels: Outlaws, Pirates, Bandits & Bushwhackers. The History Press. 2014 ISBN 9781625850676

- ^ Reader, Phil. Copperheads, Secesh Men, and Confederate Guerillas: Pro-Confederate Activities in Santa Cruz County During the Civil War. Santa Cruz Public Libraries, 1991. Archived

- ^ O’Bryan, Tony. "Jayhawkers". Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library

- ^ Johnson, Adam Rankin, and William J. Davis. The Partisan Rangers of the Confederate States Army. Louisville, Ky.: G. G. Fetter Company, 1904.

- ^ Martin, James B. Third War. Irregular Warfare on the Western Border, 1862–1865. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Combat Studies Institute Press, 2012

- ^ Schultz, Duane. Quantrill's war: the life and times of William Clarke Quantrill, 1837-1865. St. Martin's Press, 1997.

- ^ Albert Castel and Tom Goodrich. Bloody Bill Anderson: The Short, Savage Life of a Civil War Guerrilla. Stackpole Books, 1998.

- ^ O’Bryan, Tony. "Bushwhackers". Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library

- ^ Fellman, Michael. Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 126-128.ISBN 9780195064711

- ^ Sutherland, Daniel E. American Civil War Guerillas: Changing the Rules of Warfare. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2013.

- ^ Trow, Harrison, and John P Burch. Charles W. Quantrell: a True History of His Guerrilla Warfare On the Missouri And Kansas Border During the Civil War of 1861-1865. Kansas, City, Mo., 1923.

- ^ Edward E. Leslie. The Devil Knows How To Ride: The True Story Of William Clarke Quantril And His Confederate Raiders. New York: Random House, 1996. ISBN 978-0-679-42455-0

- ^ Thomas Goodrich. Bloody Dawn: The Story of the Lawrence Massacre. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1991.

- ^ Joseph M. Beilein, Jr. Of Eyes and Teeth: The Trial of George Maddox, the Raid on Lawrence, and the Bloodstained Verdict of the Guerrilla War, The Civil War Monitor

- ^ Gallery: Anti-Guerrilla Actions, NPS

- ^ Evacuation Day, The Kansas City Public Library

- ^ General Order No. 11, By Jeremy Neely, Missouri State University

- ^ Albert Castel. "Order No. 11 and the Civil War on the Border", Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 57, July 1963, pp.357-368. Archived

- ^ Rafiner, Tom A. Cinders and Silence: A Chronicle of Missouri's Burnt District. Harrisonville, Missouri: Burnt District Press, 2013.

- ^ Rafiner, Tom A. Caught between three fires: Cass County, Mo., Chaos, & Order No. 11, 1860-1865. Harrisonville, Mo. : Burnt District Press, 2010.

- ^ Andy Ostmeyer. Civil War: Order No. 11 reduced border to a wasteland, The Joplin Globe, September 24, 2011

- ^ Leo E. Huff. Guerrillas, Jayhawkers and Bushwhackers in Northern Arkansas During the Civil War, Ozark Watch, Vol. IV, No. 4, Spring 1991 / Vol. V, No. 1, Summer 1991.

- ^ Albert Castel. Frontier State at War. Kansas, 1861-1865. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1958.

- ^ Centralia Massacre and Battle Reenactment, Boone County Historical Society

- ^ Goodrich, Thomas. Black Flag: Guerrilla Warfare on the Western Border, 1861–1865. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press

- ^ The Civil War in Missouri, 1861-1865: a war within the war, The Civil war centennial Commission in Missouri

- ^ Stiles, T. J. Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

- ^ Fellman, Michael (1990). Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri onto the American Civil War. Oxford University Press, pp. 61–143. ISBN 0-19-506471-2.

- ^ Frank and Jesse James Court Documents from Daviess County, Missouri State Archive

- ^ Yeatman, Ted P. Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend. Cumberland House, 2001

- ^ Michael J. Goc. Hero of the Red River: The Life and Times of Joseph Bailey.Friendship WI: New Past Press, 2007.

Further reading

- Edwards, John Newman. Noted guerrillas, or The warfare of the border. Being a history of the lives and adventures of Quantrell, Bill Anderson, George Todd, Dave Poole, Fletcher Taylor, Peyton Long, Oll Shepherd, Arch Clements, John Maupin, Tuck and Woot Hill, Wm. Gregg, Thomas Maupin, the James brothers, the Younger brothers, Arthur McCoy, and numerous other well known guerrillas of the West. St. Louis, H.W. Brand & Co., 1879.

- Hildebrand, Samuel S. Autobiography of the renowned Missouri "Bushwhacker", and unconquerable Rob Roy of America; being his complete confession recently made to the writers and carefully compiled ... with all the facts connected with his early history.. Jefferson City, Mo.: State Times Printing House, 1870.

- Geiger, Mark W. Financial Fraud and Guerrilla Violence in Missouri's Civil War, 1861-1865. Yale University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-300-15151-0

- Mackey, Robert R. The UnCivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004

External links

- Cinders and Silence: A Chronicle of Missouri's Burnt District, 1854-1870, Missouri State Archives