Inclusive language: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Add: s2cid, pmid, authors 1-1. Removed parameters. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Political terminology | #UCB_Category 86/413 |

Discrimination is the proper subcategory of the main category bias for this article |

||

| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

[[Category:Linguistic controversies]] |

[[Category:Linguistic controversies]] |

||

[[Category:Political terminology]] |

[[Category:Political terminology]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Dysphemisms]] |

[[Category:Dysphemisms]] |

||

[[Category:Etiquette]] |

[[Category:Etiquette]] |

||

[[Category:Identity politics]] |

[[Category:Identity politics]] |

||

[[Category:Gender-neutral language]] |

[[Category:Gender-neutral language]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Revision as of 12:41, 27 December 2022

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

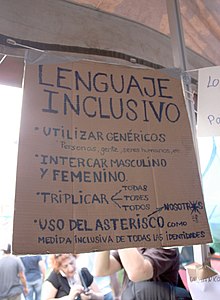

Inclusive language avoids expressions that are considered to express or imply ideas that are sexist, racist, or otherwise biased, prejudiced, or insulting to any particular group of people and sometimes animals as well. Use of inclusive language aims to avoid offense and fulfill the ideals of egalitarianism; often the term "political correctness" is used to refer to this practice, either as a neutral description by supporters or commentators in general,[1] or with negative connotations among its opponents.

Its supporters argue that language is often used to perpetuate and spread prejudice and that creating intention around using inclusive language can help create more productive, safe, and profitable organizations and societies.[2]

Definition and use

Inclusive language aims to produce content that is accessible and credible to the widest possible audience. What inclusive language actually looks like varies based on standards in education, religion, and publishing.

For media, inclusive language is often used to meet standards of journalistic objectivity. The Chicago Manual of Style states that "[b]iased language that is not central to the meaning of the work distracts many readers and makes the work less credible to them" while at the same time discouraging political use of inclusive language.[3] Similarly, the AP Stylebook recommends journalists avoid obscenities, hate speech, and the like—even in quotations—to avoid both legal liability and giving undue credibility to biased viewpoints.[4] Both guides recommend the use of phrasing like people-first language and singular they in certain cases.

Examples

| Rationale for suggested language change | Language or expression to be avoided, according to proponents | Replacement language proposed by proponents |

|---|---|---|

| Gender-neutral language to avoid implied sexism or heteronormativity |

| |

| Avoid sexism in any implication women should follow "traditional" gender roles, are in any way unequal to men, are valued primarily as wives or sex objects, or that the unpaid work of women is less important than paid work |

| |

Older terminology is disempowering, has negative connotations, or is subject to a euphemism treadmill with regard to

|

| |

| Avoid negative stereotypes |

|

|

| Avoid racism, colonialism, and religious intolerance, whether overtly or by historical association |

|

|

| Avoid sizeism and body shaming | "fat", "large", possibly "plus-sized model" or "plus-size clothing" in women's fashion | "curvy" or simply talk about "women of all sizes" |

| Avoid insulting human dignity by emphasizing the humanity of individuals rather than group label |

|

|

| Avoiding implied racism or colonialism by using indigenous names instead of names used by colonizers | Indian, Bombay, primitive cultures | Native American (see Native American name controversy), Mumbai (see Renaming of cities in India, Geographical renaming, and British Isles naming dispute), early cultures |

| Avoid offending non-Christians and non-believers (see War on Christmas) |

|

|

| Avoid implied transphobia and binary genderism | Using "he" or "she" based on appearance or name | Ask people what pronouns they prefer to be addressed by, or introduce yourself with your own gender pronouns (e.g. "My name is Chris and my pronouns are he/him/his.") |

| Taking a sex-positive position and avoiding slut-shaming | Prostitute | Sex worker |

| Avoid associations with slavery | Master/slave (technology) | Primary/secondary, leader/follower |

| Avoid association between ownership of animals and ownership of people (slavery)[7] and in general anthropocentrism | Pet owner | Pet guardian,[7] pet parent[8] |

| Avoid stigma promoting discrimination against people with HIV/AIDS | Clean | HIV negative |

The neurodiversity movement including the autism rights movement sees various neurological conditions not as diseases to be cured, but differences to be embraced, like left-handedness or homosexuality. Proponents might object to calling autism a mental disability, and might prefer "neurotypical" to "healthy" or "normal". Sometimes the word "allistic" is used to refer to people who are not autistic.[9]

Comments about personal appearance might be interpreted as lookism or sexual harassment, depending on the context.

Effects of political correctness and inclusive language

Political correctness and inclusive language go hand in hand as both focus on the use of neutral terms and expressions that typically combats prejudices. These concepts affect the psychological and social forces of the everyday lives of people.[10] Those who adopt the form of political correctness and inclusive language indirectly reject the possibilities of anything against these values. Many businesses and organizations cater to their mass audiences by choosing to indulge in or reject these ideologies. By choosing one or the other, businesses alienate themselves from the many possibilities of the opposing side.[10] For example, companies foster a sense of equality using inclusive language like gender neutral terms, therefore reducing sexism for their customers and employees.[11] However, they cast out those who do not believe in supporting the use of gender neutral terms which can either help or harm the company.

In return, many people who reject the use of these concepts outwardly express their opinions on them. It is deemed as "increasingly problematic in contemporary society" as its use has become common in today's world.[12] This has led to clashes between people of both sides which has been criticized by many as they deem the use of these ideologies to lead to culture wars.[12] Republicans and Democrats constantly battle with these terms as it is used negatively by the former and positively by the latter.

See also

- Bias-free communication

- Gender-neutral language

- Call-out culture

- Color-blind casting

- Euphemism

- List of politically motivated renamings

- Plain language

- Speech code

References

- ^ a b Krys Boyd (17 February 2015). "The Limits Of Political Correctness (panel discussion)". Think (Podcast). KERA (FM). Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Inclusive Language Guide: Definition & Examples". Rider University. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 2021-01-06.

- ^ The Chicago manual of style (17th ed.). Chicago, IL. 2017. p. 358. ISBN 978-0226287058.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Froke, Paula; Bratton, Anna Jo; McMillan, Jeff; Sarkar, Pia; Schwartz, Jerry; Vadarevu, Raghuram (2020). The Associated Press stylebook 2020-2022 (55th ed.). New York, NY. pp. 508–509. ISBN 9780917360695.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Seattle officials call for ban on 'potentially offensive' language". Fox News. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Lee, Chelsea (16 November 2015). "The Use of Singular "They" in APA Style". APA Style 6th Edition Blog. American Psychological Association. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ a b Opinion - Dog "Owner" vs "Guardian" - Words Matter

The use of the word "guardian" started in the San Francisco Bay area with an organization called In Defense of Animals (IDA). The IDA was founded in 1999 by Dr. Elliot Katz, who equated animal ownership with human slavery, declaring that we don’t "own" our pets, we simply have "guardianship" of them. Dr. Katz and his compatriots in the movement claim that the word "ownership" implies a slave/slave-master relationship. He opines that slave-masters were, by definition, cruel, so calling oneself an "owner" presumes cruelty.

- ^ Kurlander, Steven (24 March 2015). "A Pet Peeve Against 'Pet Parenting' -- Time to Push Back Against Equating Animals With Children". HuffPost. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Allistic". Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Howard S. (2010). Society against itself : political correctness and organizational self-destruction. London: Karnac Books. ISBN 978-1-84940-782-3. OCLC 743101733.

- ^ Sczesny, Sabine; Moser, Franziska; Wood, Wendy (2015). "Beyond Sexist Beliefs: How Do People Decide to Use Gender-Inclusive Language?". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 41 (7): 943–954. doi:10.1177/0146167215585727. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 26015331. S2CID 7492192.

- ^ a b Lea, John (2010-05-26). Political Correctness and Higher Education: British and American Perspectives (0 ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203888629. ISBN 978-0-203-88862-9.