Mitsubishi A6M Zero: Difference between revisions

| Line 198: | Line 198: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*[http://www.ehangar.com/aircraft/zero/ Aviation Art] depicting the Zero |

|||

* [http://www.j-aircraft.com/research/quotes/A6M.html www.j-aircraft.com: Quotes A6M] |

* [http://www.j-aircraft.com/research/quotes/A6M.html www.j-aircraft.com: Quotes A6M] |

||

* [http://www.vectorsite.net/avzero.html THE MITSUBISHI A6M ZERO at Greg Goebel's AIR VECTORS] |

* [http://www.vectorsite.net/avzero.html THE MITSUBISHI A6M ZERO at Greg Goebel's AIR VECTORS] |

||

Revision as of 19:22, 18 August 2007

The Mitsubishi A6M Zero ("A" for fighter, 6th model, "M" for Mitsubishi) was a lightweight, carrier-based fighter aircraft employed by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service from 1940 to 1945. Its history mirrored the fortunes of Imperial Japan in World War II. At the time it was introduced, the Mitsubishi A6M was the best carrier-based fighter plane in the world and was greatly feared by Allied pilots. [1] [2] [3] Tactics were developed by 1942 by Allied forces to engage the Zero on equal terms. By 1943, American and British manufacturers were producing fighters with greater firepower, armor, and speed and approaching the Zero's maneuverability. By 1944, the Mitsubishi A6M was outdated but remained in production. In shifting priorities during the final years of the War in the Pacific, the Zero was utilized in kamikaze operations.

A combination of excellent maneuverability and very long range made it one of the finest fighters of its era. In early combat operations, the Zero gained a legendary reputation, outclassing its contemporaries. Later, design weaknesses and the increasing scarcity of more powerful aircraft engines meant that the Zero became less effective against newer fighters.

Design and development

The Mitsubishi A5M fighter was just starting to enter service in early 1937 when the Imperial Japanese Navy started looking for its eventual replacement. In May they issued specification 12-Shi for a new aircraft carrier-based fighter, sending it to Nakajima and Mitsubishi. Both firms started preliminary design work while they awaited more definitive requirements to be handed over in a few months.

Based on the experiences of the A5M in China, the Navy sent out updated requirements in October. The new requirements called for a speed of 500 km/h at 4000 m and a climb to 3000 m in 3.5 min. They needed an endurance of two hours at normal power, or six to eight hours at economical cruising speed (both with drop tanks). Armament was to consist of two 20 mm cannon and two 7.7 mm machine guns and two 30 kg or 60 kg bombs. A complete radio set was to be mounted in all airplanes, along with a radio direction finder for long-range navigation. The maneuverability was to be at least equal to that of the A5M, while the wing span had to be less than 12 m to fit on the carriers.

Nakajima's team thought the new requirements were impossible to achieve and pulled out of the competition in January. Mitsubishi's chief designer, Jiro Horikoshi, felt that the requirements could be met, but only if the aircraft could be made as light as possible. Every weight-saving method was used; the designers made extensive use of the new duralumin alloy (see below). With its low-wing cantilever monoplane layout, retractable wide-set landing gear and enclosed cockpit, the design was not only much more modern than any the Navy had used in the past, it was one of the most modern in the world.

The A6M was a more spartan design than contemporary western aircraft. Unlike other contemporary fighters, there was no armor plate to protect the single pilot, and no self-sealing fuel tanks. Most of the airplane was built of T-7178 aluminum, a top-secret variety developed by the Japanese for the purpose. It was lighter and stronger than the normal aluminum used at the time, but more brittle. The Zero had a fairly high-lift, low-speed wing with a very low wing loading, giving it a very low stalling speed of well below 60 knots. This is the reason for the phenomenal turning ability (imposition of g-load on the wings in a turn before an accelerated stall occurs) of the airplane, allowing it to turn more sharply than any Allied fighter of the time. Roll rate is enhanced by servo tabs on the ailerons which deflect opposite to the ailerons and make the control force much lighter. The disadvantage is that they reduce the maximum roll effect at full travel. At 160 mph (260 km/h) the A6M2 had a roll rate of 56 degrees per second. Because of wing flexibility, roll effectiveness dropped to near zero at about 300 mph indicated airspeed.

The American military discovered many of the A6M's unique attributes, when they recovered a mostly intact specimen at Alaska. The Japanese pilot had strayed too far away from base and hoped to make an emergency landing in US territory but the plane flipped over and his neck was broken.

Name

It is universally known as Zero from its Japanese Navy designation, Type 0 Carrier Fighter (Rei shiki Kanjo sentoki, 零式艦上戦闘機), taken from the last digit of the Imperial year 2600 (1940), when it entered service. In Japan it was unofficially referred to as both Rei-sen and Zero-sen. The official Allied code name was Zeke (Hamp for the A6M3 model 32 variant); while this was in keeping with standard practice of giving boys' names to fighters, it is not definitely known if this was chosen for its similarity to "Zero."

Operational history

The pre-series A6M2 Zero became known in 1940-41, when the fighter destroyed 266 confirmed aircraft in China. At the time of Pearl Harbor, there were 420 Zeros active in the Pacific. The carrier-borne Model 21 was the type encountered by the Americans, often much further from its carriers than expected, with a mission range of over 1600 statute miles (2,600 km). The Zero fighters were superior in many aspects of performance to all Allied fighters in the Pacific in 1941 and quickly gained a great reputation. However, the Zero failed to achieve complete air superiority due to the development of suitable tactics and new aircraft by the Allies. During WWII the Zero destroyed at least 1,550 American planes.

The Japanese ace Saburo Sakai described how the resilience of early Allied aircraft was a factor in preventing the Zeros from total domination: [4]

I had full confidence in my ability to destroy the Grumman and decided to finish off the enemy fighter with only my 7.7mm machine guns. I turned the 20mm. cannon switch to the 'off' position, and closed in. For some strange reason, even after I had poured about five or six hundred rounds of ammunition directly into the Grumman, the airplane did not fall, but kept on flying. I thought this very odd - it had never happened before - and closed the distance between the two airplanes until I could almost reach out and touch the Grumman. To my surprise, the Grumman's rudder and tail were torn to shreds, looking like an old torn piece of rag. With his plane in such condition, no wonder the pilot was unable to continue fighting! A Zero which had taken that many bullets would have been a ball of fire by now.

Designed for attack, the Zero gave precedence to maneuverability and firepower at the expense of protection — most had no self-sealing tanks or armor plate — thus many Zeros were lost too easily in combat along with their pilots. Ironically, up to the initial phases of the Pacific conflict, the Japanese trained their aviators far more strenuously than their Allied counterparts. However, unexpectedly heavy pilot losses at the Coral Sea and Midway made them difficult to replace.

With the extreme agility of the Zero, the Allied pilots found that the appropriate combat tactic against Zeros was to remain out of range and fight on the dive and climb. By using speed and resisting the deadly error of trying to out-turn the Zero, eventually cannon or heavy machine guns could be brought to bear and a single burst of fire was usually enough to down the Zero. These tactics, known as boom-and-zoom, were successfully employed in the CBI against similarly maneuverable Japanese Army aircraft such as the Ki-27 and Nakajima Ki-43 by the Flying Tigers (American Volunteer Group). AVG pilots were trained to exploit the advantages of their P-40s; very sturdy, heavily armed, generally faster in a dive and in level flight at low altitude, with a good rate of roll.

Another important maneuver was called the "Thach Weave," named for the man that invented it, then-Lt Cdr John S. "Jimmy" Thach. It required two planes, a leader and his wingman, to fly about 200 feet apart. When a Zero would latch onto the tail of one of the fighters, the two planes would turn toward each other. If the Zero followed its original target through the turn, it would come into a position to be fired on by his target's wingman. This tactic was used with spectacular results at the Battle of the Coral Sea and at the Battle of Midway, helping make up for the inferiority of the US planes until new aircraft types were brought into service.

When the powerful Grumman F6F Hellcat, Vought F4U Corsair and Lockheed P-38 appeared in the Pacific theater, the A6M with its low-powered engine lost its competitiveness. The US Navy's 1:1 kill ratio suddenly jumped to better than 10:1. While the Hellcat and Corsair are generally considered to better all-around than the Zero, US successes also had to do with the increasingly inexperienced Japanese aviators.

Nonetheless, until the end of the war, in competent hands, the Zero could still be deadly. Because of the scarcity of high-powered aviation engines and some problems with planned successor models, the Zero remained in production until 1945, with over 11,000 of all types produced.

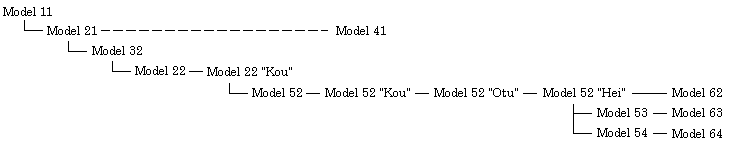

Variants

- A6M1, Type 0 Prototypes

The first A6M1 prototype was completed in March 1939, powered by the 780 hp (580 kW) Mitsubishi Zuisei 13 engine with a two-bladed propeller. It first flew on 1 April, and passed testing in a remarkably short period of time. By September it had already been accepted for Navy testing as the A6M1 Type 0 Carrier Fighter, with the only notable change being a switch to a three-bladed propeller to cure a vibration problem.

- A6M2, Type 0 Model 11

While the Navy was testing the first two prototypes, they suggested that the third be fitted with the 940 hp (700 kW) Nakajima Sakae 12 engine instead. Mitsubishi had its own engine of this class in the form of the Kinsei, so they were somewhat reluctant to use the Sakae. Nevertheless when the first A6M2 was completed in January 1940, the Sakae's extra power pushed the performance of the plane well past the original specifications.

The new version was so promising that the Navy had 15 built and shipped to China before they had completed testing. They arrived in Manchuria in July 1940, and first saw combat over Chungking in August. There they proved to be completely untouchable by the Polikarpov I-16s and I-153s that had been such a problem for the A5Ms currently in service. In one encounter 13 Zeros shot down 27 I-15s and I-16s in under three minutes without loss. After hearing of these reports the Navy immediately ordered the plane into production as the Type 0 Carrier Fighter, Model 11.

Reports of the Zero's performance filtered back to the US slowly. There they were dismissed by most military officials, who felt it was impossible for the Japanese to build such an aircraft.

- A6M2, Type 0 Model 21

After the delivery of only 65 planes by November 1940, a further change was worked into the production lines, which introduced folding wingtips to allow them to fit on the aircraft carriers. The resulting Model 21 would become one of the most produced versions early in the war. When the lines switched to updated models, 740 Model 21s were completed by Mitsubishi, and another 800 by Nakajima. Two other versions of the Model 21 were built in small numbers, the Nakajima-built A6M2-N "Rufe" floatplane (based on the model 11 with a slightly modified tail), and the A6M2-K two-seat trainer of which a total of 508 were built by Hitachi and the Sasebo Naval Air Arsenal.

- A6M3, Type 0 Model 32

In late 1941, Nakajima introduced the Sakae 21, which used a two speed supercharger for better altitude performance, and increased power to 1,130 hp (840 kW). Plans were made to introduce the new engine into the Zero as soon as possible.

The new Sakae was slightly heavier and somewhat longer due to the larger supercharger, which moved the center of gravity too far forward on the existing airframe. To correct for this the engine mountings were cut down by 8 inches (200 mm), moving the engine back towards the cockpit. This had the side effect of reducing the size of the main fuel tank (located to the rear of the engine) from 518 litres to 470 litres.

The only other major changes were to the wings, which were simplified by removing the Model 21's folding tips. This changed the appearance enough to prompt the US to designate it with a new code name Hamp, before realizing it was simply a new model of the Zeke. The wings also included larger ammunition boxes, allowing for 100 rounds for each of the 20 mm cannon.

The wing changes had much greater effects on performance than expected. The smaller size led to better roll, and their lower drag allowed the diving speed to be increased to 360 knots (670 km/h). On the downside, maneuverability was reduced, and range suffered due to both decreased lift and the smaller fuel tank. Pilots complained about both. The shorter range proved a significant limitation during the Solomons campaign of 1942.

The first Model 32 deliveries began in April 1942, but it remained on the lines only for a short time, with a run of 343 being built.

- A6M3, Type 0 Model 22

In order to correct the deficiencies of the Model 32, a new version with the Model 21's folding wings, new in-wing fuel tanks and attachments for a 330 litre drop tank under each wing were introduced. The internal fuel was thereby increased to 570 litres in this model, regaining all of the lost range.

As the airframe was reverted from the Model 32 and the engine remained the same, this version received the navy designation Model 22, while Mitsubishi called it the A6M3a. The new model started production in December, and 560 were eventually produced. This company constructed some examples for evaluation, armed with 30 mm Type 5 Cannon, under denomination of A6M3b (model 22b).

- A6M4

The A6M4 designation was applied to two A6M2s fitted with an experimental turbo-supercharged Sakae engine designed for high-altitude use. The design, modification and testing of these two prototypes was the responsibility of the Dai-Ichi Kaigun Gijitshusho (First Naval Air Technical Arsenal) at Yokosuka and took place in 1943. Lack of suitable alloys for use in the manufacture of the turbo-supercharger and its related ducting caused numerous ruptures of the ducting resulting in fires and poor performance. Consequently, further development of the A6M4 was cancelled. The program still provided useful data for future aircraft designs and, consequently, the manufacture of the more conventional A6M5, already under development by Mitsubishi Jukogyo K.K., was accelerated. [5]

- A6M5, Type 0 Model 52

The A6M5 was a modest update of the A6M3 Model 22, with nonfolding wing tips and thicker skinning to permit faster diving speeds, plus an improved exhaust system (four pipes on each side) that provided an increment of thrust. Improved roll-rate of the clipped-wing A6M3 was now built in.

Sub-variants included:

- "A6M5a Model 52a «Kou»," featuring Type 99-II cannon with belt feed of the Mk 4 instead of drum feed Mk 3 (100 rpg), permitting a bigger ammunition supply (125 rpg)

- "A6M5b Model 52b «Otsu»," with an armor glass windscreen, a fuel tank fire extinguisher and one 7.7 millimeter Type 97 gun (750 m/s muzzle velocity and 600 m range) in the cowling replaced by a 13.2 millimeter Type 3 Browning-derived gun (790 m/s muzzle velocity and 900 m range) with 240 rounds

- "A6M5c Model 52c «Hei»" with more armor plate on the cabin's windshield (5.5 cm) and in the pilot's seat. This version also possessed armament of three 13.2 millimeter guns (one in the cowling, and one in each wing with a rate of fire at 800 rpm), twin 20 millimeter Type 99-II guns and an additional fuel tank with a capacity of 367 liters, often replaced by a 250 kg bomb.

The A6M5 could travel at 540 km/h and reach a height of 8000 meters in nine minutes, 57 seconds. Other variants are the night fighter A6M5d-S (modified for night combat, armed with one 20 mm type 99 cannon, inclined back to the pilot's cockpit) and A6M5-K "Zero-Reisen"(model l22) tandem trainer version, also manufactured by Mitsubishi.

- A6M6c

This was similar to the A6M5c, but with self-sealing wing tanks and a Nakajima Sakae 31a engine featuring water-methanol engine boost.

- A6M7, Type 0 Model 63

Similar to the A6M6 but intended for attack or Kamikaze role.

- A6M8

Similar to the A6M6 but with Mitsubishi Kinsei 62 engine, two prototypes built.

Operators

- Chinese Nationalist Air Force operated small number of captured aircraft.

- In 1945, Indonesian guerillas captured a small number of Zero aircraft at numerous ex-Japanese air bases including Bugis Air Base in Malang (repatriated 18 September 1945). Most of the aircraft were destroyed during 1945-1949 when the former Dutch East Indies and the Netherlands were engaged in military conflict/police action in Indonesia. Small numbers of surviving aircraft were saved in Kalijati Air Base, near Subang, West Java.

Survivors

Several Zero fighters survived the war and are on display in Japan (in Aichi, Hamamatsu and Shizuoka), China (in Beijing), United States (at the National Museum of the United States Air Force), and the UK (Duxford) as well as the Auckland War Museum in New Zealand.

A number of flyable Zero airframes exist; most have had their engines replaced with similar American units; only one, the Planes of Fame Museum's example, bearing tail number "61-120" (see external link below) has the original Sakae engine [1]. Although not truly a survivor, the "Blayd" Zero is a reconstruction based on templating original Zero components recovered from the South Pacific; a small fraction of parts in the reconstruction are from original Zero landing gears.[6][7] The aircraft is now on display at the Fargo Air Museum in Fargo, North Dakota.

Specifications (A6M2 Type 0 Model 21)

Data from The Great Book of Fighters[8]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Aspect ratio: 6.4

Performance

Armament

- Guns:

- 2× 7.7 mm (0.303 in) type 97 machine guns in the engine cowling

- 2× 20 mm (0.787 in) type 99 cannons in the wings

- Bombs:

- 2× 66 lb (30 kg) and

- 1× 132 lb (60 kg) bombs or

- 2× fixed 250 kg (550 lb) bombs for kamikaze attacks

References

- ^ Hawks, Chuck. The Best Fighter Planes of World War II. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ The American and Japanese Air services Compared. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ Mersky, Peter B. (Cmdr. USNR). Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons, 1942-1944 Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ Saburo Sakai: "Zero"

- ^ A6M4 entry at the J-Aircraft.com website

- ^ Blayd Corporation Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ Examination of Blayd Zero Artifacts] Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ Green and Swanborough 2001

- Green, William and Swanborough, Gordon. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Nohara, Shigeru. A6M Zero (In Action #59). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1983. ISBN 0-89747-141-5.

- Okumiya, Masatake and Hiroikoski, Jiro (with Caidin, Martin). Zero! The Story of Japan's Air War in the Pacific: 1941-45. New York: Ballantine Books, 1956. No ISBN.

- Sajaida, Henry. The Siege of Rabaul. St. Paul, Minnesota: Phalanx Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-883809-09-6.

- Sheftall, M.G. Blossoms in the Wind: Human Legacies of the Kamikaze. New York: NAL Caliber, 2005. ISBN 0-451-21487-0.

- Willmott, H.P. Zero A6M. London: Bison Books, 1980. ISBN 0-89009-322-9.

External links

- Aviation Art depicting the Zero

- www.j-aircraft.com: Quotes A6M

- THE MITSUBISHI A6M ZERO at Greg Goebel's AIR VECTORS

- Imperial Japanese Navy's Mitsubishi A6M Reisen

- Planes of Fame Museum's Flightworthy A6M5 Zero

- War Prize: The Capture of the First Japanese Zero Fighter in 1941

Related content

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Bell XP-77

- Curtiss-Wright CW-21

- Curtiss P-40 Warhawk

- Grumman Wildcat

- Messerschmitt Bf 109

- Nakajima Ki-43

- Supermarine Spitfire

Related lists