Project management: Difference between revisions

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

The tasks are also prioritized, dependencies between tasks are identified, and this information is documented in a project schedule. The dependencies between the tasks can affect the length of the overall project (dependency constrained), as can the availability of resources (resource constrained). Project Managers will often make a call to [[double down]] to prevent a project from breaking deadlines in the final stages of the implementation phase. Time is not considered a cost nor a resource since the project manager cannot control the rate at which it is expended. This makes it different from all other resources and cost categories. It should be remembered that no effort expended will have any higher quality than that of the effort- expenders. |

The tasks are also prioritized, dependencies between tasks are identified, and this information is documented in a project schedule. The dependencies between the tasks can affect the length of the overall project (dependency constrained), as can the availability of resources (resource constrained). Project Managers will often make a call to [[double down]] to prevent a project from breaking deadlines in the final stages of the implementation phase. Time is not considered a cost nor a resource since the project manager cannot control the rate at which it is expended. This makes it different from all other resources and cost categories. It should be remembered that no effort expended will have any higher quality than that of the effort- expenders. |

||

sss |

|||

===Cost=== |

===Cost=== |

||

Revision as of 19:17, 25 January 2008

Project management is the discipline of organizing and managing resources (e.g. people) in a way that the project is completed within defined scope, quality, time and cost constraints. A project is a temporary and one-time endeavor undertaken to create a unique product or service, which brings about beneficial change or added value. This property of being a temporary and one-time undertaking contrasts with processes, or operations, which are permanent or semi-permanent ongoing functional work to create the same product or service over and over again. The management of these two systems is often very different and requires varying technical skills and philosophy, hence requiring the development of project managements.

The first challenge of project management is to make sure that a project is delivered within defined constraints. The second, more ambitious challenge is the optimized allocation and integration of inputs needed to meet pre-defined objectives. A project is a carefully defined set of activities that use resources (money, people, materials, energy, space, provisions, communication, etc.) to meet the pre-defined objectives.

History of project management

As a discipline, project management developed from different fields of application including construction, engineering, and defense. In the United States, the forefather of project management is Henry Gantt, called the father of planning and control techniques, who is famously known for his use of the Gantt chart as a project management tool, for being an associate of Frederick Winslow Taylor's theories of scientific management[1], and for his study of the work and management of Navy ship building. His work is the forerunner to many modern project management tools including the work breakdown structure (WBS) and resource allocation.

The 1950s marked the beginning of the modern project management era. Again, in the United States, prior to the 1950s, projects were managed on an ad hoc basis using mostly Gantt Charts, and informal techniques and tools. At that time, two mathematical project scheduling models were developed: (1) the "Program Evaluation and Review Technique" or PERT, developed by Booz-Allen & Hamilton as part of the United States Navy's (in conjunction with the Lockheed Corporation) Polaris missile submarine program[2]; and (2) the "Critical Path Method" (CPM) developed in a joint venture by both DuPont Corporation and Remington Rand Corporation for managing plant maintenance projects. These mathematical techniques quickly spread into many private enterprises.

At the same time, technology for project cost estimating, cost management, and engineering economics was evolving, with pioneering work by Hans Lang and others. In 1956, the American Association of Cost Engineers (now AACE International; the Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering) was formed by early practitioners of project management and the associated specialties of planning and scheduling, cost estimating, and cost/schedule control (project control). AACE has continued its pioneering work and in 2006 released the first ever integrated process for portfolio, program and project management(Total Cost Management Framework).

In 1969, the Project Management Institute (PMI) was formed to serve the interest of the project management industry. The premise of PMI is that the tools and techniques of project management are common even among the widespread application of projects from the software industry to the construction industry. In 1981, the PMI Board of Directors authorized the development of what has become A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), containing the standards and guidelines of practice that are widely used throughout the profession. The International Project Management Association (IPMA), founded in Europe in 1967, has undergone a similar development and instituted the IPMA Competence Baseline (ICB). The focus of the ICB also begins with knowledge as a foundation, and adds considerations about relevant experience, interpersonal skills, and competence. Both organizations are now participating in the development of a ISO project management standard.

Definitions

- PMBOK (Project Management Body of Knowledge as defined by the Project Management Institute - PMI):"Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, tools and techniques to project activities to meet project requirements."[3]

- PRINCE2 project management methodology: "The planning, monitoring and control of all aspects of the project and the motivation of all those involved in it to achieve the project objectives on time and to the specified cost, quality and performance."[4]

- PROJECT: A temporary piece of work with a finite end date undertaken to create a unique product or service. Projects bring form or function to ideas or needs.

- DIN 69901 (Deutsches Institut für Normung - German Organization for Standardization): "Project management is the complete set of tasks, techniques, tools applied during project execution"

Job description

Project management is quite often the province and responsibility of an individual project manager. This individual seldom participates directly in the activities that produce the end result, but rather strives to maintain the progress and productive mutual interaction of various parties in such a way that overall risk of failure is reduced.

A project manager is often a client representative and has to determine and implement the exact needs of the client, based on knowledge of the firm he/she is representing. The ability to adapt to the various internal procedures of the contracting party, and to form close links with the nominated representatives, is essential in ensuring that the key issues of cost, time, quality, and above all, client satisfaction, can be realized.

In whatever field, a successful project manager must be able to envision the entire project from start to finish and to have the ability to ensure that this vision is realized.

Any type of product or service —buildings, vehicles, electronics, computer software, financial services, etc.— may have its implementation overseen by a project manager and its operations by a product manager.

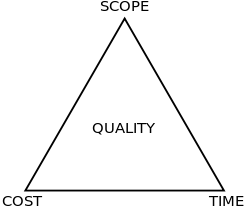

The traditional triple constraints

Like any human undertaking, projects need to be performed and delivered under certain constraints. Traditionally, these constraints have been listed as scope, time, and cost [citation needed]. These are also referred to as the Project Management Triangle, where each side represents a constraint. One side of the triangle cannot be changed without impacting the others. A further refinement of the constraints separates product 'quality' or 'performance' from scope, and turns quality into a fourth constraint.

- The diagram shown here, often a project management triangle focuses on the trade-off between time, cost, and quality (see also Project triangle where these aspects are called fast, cheap, and good). The deviation claimed to be traditional (without citation) bears the significant difference that quality as a combination of other aspects is at best something like "process quality", and certainly not product quality. Thus this diagram represents a biased (and often inappropriate) view of what quality is, from the perspective of self-assessment of project managers, who are in many company cultures often perceived as pursuing more their own career than actual product or project qualities. For this reason this section should be generally revised by an unbiased expert.

The time constraint refers to the amount of time available to complete a project. The cost constraint refers to the budgeted amount available for the project. The scope constraint refers to what must be done to produce the project's end result. These three constraints are often competing constraints: increased scope typically means increased time and increased cost, a tight time constraint could mean increased costs and reduced scope, and a tight budget could mean increased time and reduced scope.

The discipline of project management is about providing the tools and techniques that enable the project team (not just the project manager) to organize their work to meet these constraints.

Another approach to project management is to consider the three constraints as finance, time and human resources. If you need to finish a job in a shorter time, you can throw more people at the problem, which in turn will raise the cost of the project, unless by doing this task quicker we will reduce costs elsewhere in the project by an equal amount.

Time

For analytical purposes, the time required to produce a deliverable is estimated using several techniques. One method is to identify tasks needed to produce the deliverables documented in a work breakdown structure or WBS. The work effort for each task is estimated and those estimates are rolled up into the final deliverable estimate.

The tasks are also prioritized, dependencies between tasks are identified, and this information is documented in a project schedule. The dependencies between the tasks can affect the length of the overall project (dependency constrained), as can the availability of resources (resource constrained). Project Managers will often make a call to double down to prevent a project from breaking deadlines in the final stages of the implementation phase. Time is not considered a cost nor a resource since the project manager cannot control the rate at which it is expended. This makes it different from all other resources and cost categories. It should be remembered that no effort expended will have any higher quality than that of the effort- expenders.

sss

Cost

Cost to develop a project depends on several variables including (chiefly): resource quantities, labor rates, material rates, risk management (i.e.cost contingency), Earned value management, plant (buildings, machines, etc.), equipment, cost escalation, indirect costs, and profit.

Scope

Requirements specified for the end result. The overall definition of what the project is supposed to accomplish, and a specific description of what the end result should be or accomplish. A major component of scope is the quality of the final product. The amount of time put into individual tasks determines the overall quality of the project. Some tasks may require a given amount of time to complete adequately, but given more time could be completed exceptionally. Over the course of a large project, quality can have a significant impact on time and cost (or vice versa).

Together, these three constraints have given rise to the phrase "On Time, On Spec, On Budget". In this case, the term "scope" is substituted with "spec(ification)".

Project management activities

Project management is composed of several different types of activities such as:

- Analysis & design of objectives and events

- Planning the work according to the objectives

- Assessing and controlling risk (or Risk Management)

- Estimating resources

- Allocation of resources

- Organizing the work

- Acquiring human and material resources

- Assigning tasks

- Directing activities

- Controlling project execution

- Tracking and reporting progress (Management information system)

- Analyzing the results based on the facts achieved

- Defining the products of the project

- Forecasting future trends in the project

- Quality Management

- Issues management

- Issue solving

- Defect prevention

- Identifying, managing & controlling changes

- Project closure (and project debrief)

- Communicating to stakeholders

- Increasing/ decreasing a company's workers

Project objectives

Project objectives define target status at the end of the project, reaching of which is considered necessary for the achievement of planned benefits. They can be formulated as S.M.A.R.T.

- Specific,

- Measurable (or at least evaluable) achievement,

- Achievable (recently Acceptable is used regularly as well),

- Realistic and

- Time terminated (bounded).

The evaluation (measurement) occurs at the project closure. However a continuous guard on the project progress should be kept by monitoring and evaluating.

Project management artifacts

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (November 2007) |

Most successful projects have one thing that is very evident - they were adequately documented, with clear objectives and deliverables.[citation needed] These documents are a mechanism to align sponsors, clients, and project team's expectations.

- Project Charter

- Preliminary Scope Statement / Statement of work

- Business case/Feasibility Study

- Scope Statement / Terms of reference

- Project management plan / Project Initiation Document

- Work Breakdown Structure

- Change Control Plan

- Risk Management Plan

- Risk Breakdown Structure

- Communications Plan

- Governance Model

- Risk Register

- Issue Log

- Action Item List

- Resource Management Plan

- Project Schedule

- Status Report

- Responsibility assignment matrix

- Database of lessons learned

- Stakeholder Analysis

These documents are normally hosted on a shared resource (i.e., intranet web page) and are available for review by the project's stakeholders (except for the Stakeholder Analysis, since this document comprises personal information regarding certain stakeholders. Only the Project Manager has access to this analysis). Changes or updates to these documents are explicitly outlined in the project's configuration management (or change control plan).

Project control variables

Project Management tries to gain control over variables such as risk:

- Risk

- Potential points of failure: Most negative risks (or potential failures) can be overcome or resolved, given enough planning capabilities, time, and resources. According to some definitions (including PMBOK Third Edition) risk can also be categorized as "positive--" meaning that there is a potential opportunity, e.g., complete the project faster than expected.

Customers (either internal or external project sponsors) and external organizations (such as government agencies and regulators) can dictate the extent of three variables: time, cost, and scope. The remaining variable (risk) is managed by the project team, ideally based on solid estimation and response planning techniques. Through a negotiation process among project stakeholders, an agreement defines the final objectives, in terms of time, cost, scope, and risk, usually in the form of a charter or contract.

To properly control these variables a good project manager has a depth of knowledge and experience in these four areas (time, cost, scope, and risk), and in six other areas as well: integration, communication, human resources, quality assurance, schedule development, and procurement.

Approaches

There are several approaches that can be taken to managing project activities including agile, interactive, incremental, and phased approaches.

Regardless of the approach employed, careful consideration needs to be given to clarify surrounding project objectives, goals, and importantly, the roles and responsibilities of all participants and stakeholders.

The traditional approach

A traditional phased approach identifies a sequence of steps to be completed. In the traditional approach, we can distinguish 5 components of a project (4 stages plus control) in the development of a project:

- project initiation stage;

- project planning or design stage;

- project execution or production stage;

- project monitoring and controlling systems;

- project completion stage.

Not all the projects will visit every stage as projects can be terminated before they reach completion. Some projects probably don't have the planning and/or the monitoring. Some projects will go through steps 2, 3 and 4 multiple times.

Many industries utilize variations on these stages. For example, in bricks and mortar architectural design, projects typically progress through stages like Pre-Planning, Conceptual Design, Schematic Design, Design Development, Construction Drawings (or Contract Documents), and Construction Administration. In software development, this approach is often known as 'waterfall development' i.e. one series of tasks after another in linear sequence. In software development many organizations have adapted the Rational Unified Process (RUP) to fit this methodology, although RUP does not require or explicitly recommend this practice. Waterfall development can work for small tightly defined projects, but for larger projects of undefined or unknowable scope, it is less suited. The Cone of Uncertainty explains some of this as the planning made on the initial phase of the project suffers from a high degree of uncertainty. This becomes specially true as software development is often the realization of a new or novel product, this method has been widely accepted as ineffective for software projects where requirements are largely unknowable up front and susceptible to change. While the names may differ from industry to industry, the actual stages typically follow common steps to problem solving--defining the problem, weighing options, choosing a path, implementation and evaluation.

- Inception - Identify the initial scope of the project, a potential architecture for the system, and obtain initial project funding and stakeholder acceptance.

- Elaboration - Prove the architecture of the system.

- Construction - Build working software on a regular, incremental basis which meets the highest-priority needs of project stakeholders.

- Transition - Validate and deploy the system into the production environment

Temporary organization sequencing concepts

- Action-based entrepreneurship

- Fragmentation for commitment-building

- Planned isolation

- Institutionalised termination

Critical Chain

Critical chain is the application of the Theory of Constraints (TOC) to projects. The goal is to increase the rate of throughput (or completion rates) of projects in an organization. Applying the first three of the five focusing steps of TOC, the system constraint for all projects is identified as resources. To exploit the constraint, tasks on the critical chain are given priority over all other activities. Finally, projects are planned and managed to ensure that the critical chain tasks are ready to start as soon as the needed resources are available, subordinating all other resources to the critical chain.

For specific projects, the project plan is resource-leveled, and the longest sequence of resource-constrained tasks is identified as the critical chain. In multi-project environments, resource leveling should be performed across projects. However, it is often enough to identify (or simply select) a single "drum" resource—a resource that acts as a constraint across projects—and stagger projects based on the availability of that single resource.

Extreme Project Management

In critical studies of project management, it has been noted that several of these fundamentally PERT-based models are not well suited for the multi-project company environment of today. Most of them are aimed at very large-scale, one-time, non-routine projects, and nowadays all kinds of management are expressed in terms of projects. Using complex models for "projects" (or rather "tasks") spanning a few weeks has been proven to cause unnecessary costs and low maneuverability in several cases. Instead, project management experts try to identify different "lightweight" models, such as Extreme Programming for software development and Scrum techniques. The generalization of Extreme Programming to other kinds of projects is extreme project management, which may be used in combination with the process modeling and management principles of human interaction management.

Event chain methodology

Event chain methodology is the next advance beyond critical path method and critical chain project management.

Event chain methodology is an uncertainty modeling and schedule network analysis technique that is focused on identifying and managing events and event chains that affect project schedules. Event chain methodology helps to mitigate the negative impact of psychological heuristics and biases, as well as to allow for easy modeling of uncertainties in the project schedules. Event chain methodology is based on the following major principles.

- Probabilistic moment of risk: An activity (task) in most real life processes is not a continuous uniform process. Tasks are affected by external events, which can occur at some point in the middle of the task.

- Event chains: Events can cause other events, which will create event chains. These event chains can significantly affect the course of the project. Quantitative analysis is used to determine a cumulative effect of these event chains on the project schedule.

- Critical events or event chains: The single events or the event chains that have the most potential to affect the projects are the “critical events” or “critical chains of events.” They can be determined by the analysis.

- Project tracking with events: If a project is partially completed and data about the project duration, cost, and events occurred is available, it is possible to refine information about future potential events and helps to forecast future project performance.

- Event chain visualization: Events and event chains can be visualized using event chain diagrams on a Gantt chart.

Process-based management

Also furthering the concept of project control is the incorporation of process-based management. This area has been driven by the use of Maturity models such as the CMMI (Capability Maturity Model Integration) and ISO/IEC15504 (SPICE - Software Process Improvement and Capability Determination), which have been far more successful.

Agile project management approaches based on the principles of human interaction management are founded on a process view of human collaboration. This contrasts sharply with traditional approach. In the agile software development or flexible product development approach, the project is seen as a series of relatively small tasks conceived and executed as the situation demands in an adaptive manner, rather than as a completely pre-planned process.

Project systems

As mentioned above, traditionally, project development includes five elements: control systems and four stages.

Project control systems

Project control is that element of a project that keeps it on-track, on-time, and within budget. Project control begins early in the project with planning and ends late in the project with post-implementation review, having a thorough involvement of each step in the process. Each project should be assessed for the appropriate level of control needed: too much control is too time consuming, too little control is too costly. If control is not implemented correctly, the cost to the business should be clarified in terms of errors, fixes, and additional audit fees. The practices of project control are part of the field of cost engineering.

Control systems are needed for cost, risk, quality, communication, time, change, procurement, and human resources. In addition, auditors should consider how important the projects are to the financial statements, how reliant the stakeholders are on controls, and how many controls exist. Auditors should review the development process and procedures for how they are implemented. The process of development and the quality of the final product may also be assessed if needed or requested. A business may want the auditing firm to be involved throughout the process to catch problems earlier on so that they can be fixed more easily. An auditor can serve as a controls consultant as part of the development team or as an independent auditor as part of an audit.

Businesses sometimes use formal systems development processes. These help assure that systems are developed successfully. A formal process is more effective in creating strong controls, and auditors should review this process to confirm that it is well designed and is followed in practice. A good formal systems development plan outlines:

- A strategy to align development with the organization’s broader objectives

- Standards for new systems

- Project management policies for timing and budgeting

- Procedures describing the process

Project development stages

Regardless of the methodology used, the project development process will have the same major stages: initiation, development, production or execution, and closing/maintenance.

Initiation

The initiation stage determines the nature and scope of the development. If this stage is not performed well, it is unlikely that the project will be successful in meeting the business’s needs. The key project controls needed here are an understanding of the business environment and making sure that all necessary controls are incorporated into the project. Any deficiencies should be reported and a recommendation should be made to fix them.

The initiation stage should include a cohesive plan that encompasses the following areas:

- Study analyzing the business needs in measurable goals.

- Review of the current operations.

- Conceptual design of the operation of the final product.

- Equipment requirement.

- Financial analysis of the costs and benefits including a budget.

- Select stake holders, including users, and support personnel for the project.

- Project charter including costs, tasks, deliverables, and schedule.

Planning and design

After the initiation stage, the system is designed. Occasionally, a small prototype of the final product is built and tested. Testing is generally performed by a combination of testers and end users, and can occur after the prototype is built or concurrently. Controls should be in place that ensure that the final product will meet the specifications of the project charter. The results of the design stage should include a product design that:

- Satisfies the project sponsor, end user, and business requirements.

- Functions as it was intended.

- Can be produced within quality standards.

- Can be produced within time and budget constraints.

Closing and maintenance

Closing includes the formal acceptance of the project and the ending thereof. Administrative activities include the archiving of the files and documenting lessons learned.

Maintenance is an ongoing process, and it includes:

- Continuing support of end users

- Correction of errors

- Updates of the software over time

In this stage, auditors should pay attention to how effectively and quickly user problems are resolved.

Over the course of any construction project, the work scope changes. Change is a normal and expected part of the construction process. Changes can be the result of necessary design modifications, differing site conditions, material availability, contractor-requested changes, value engineering and impacts from third parties, to name a few. Beyond executing the change in the field, the change normally needs to be documented to show what was actually constructed. Hence, the owner usually requires a final record to show all changes or, more specifically, any change that modifies the tangible portions of the finished work. The record is made on the contract documents – usually, but not necessarily limited to, the design drawings. The end product of this effort is what the industry terms as-built drawings, or more simply, “asbuilts.” The requirement for providing them is a norm in construction contracts.

Project management tools

Project management tools include

- Financial tools

- Cause and effect charts

- PERT charts

- Gantt charts

- Event Chain Diagrams

- Run charts

- Project Cycle Optimisation

- List of project management software

- Participatory Impact Pathways Analysis (An approach for developing common understanding and consensus amongst project partcipants and stakeholders as to how the project will achieve its goal)

Project management associations

Several national and professional associations exist which have as their aim the promotion and development of project management and the project management profession. The most prominent associations include:

- The Project Management Institute (PMI)

- The Agile Project Leadership Network (APLN)

- The Association for Project Management (UK) (APM)

- The Australian Institute of Project Management (AIPM)

- The International Project Management Association (IPMA)

- The Brazilian Association for Project Management (ABGP)

- The International Association of Project and Program Management (IAPPM)

International standards

There have been several attempts to develop project management standards, such as:

- A Framework for Performance Based Competency Standards for Global Level 1 and Level 2 Project Managers (Global Alliance for Project Performance Standards)

- A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide)

- The Standard for Program Management

- The Standard for Portfolio Management

- APM Body of Knowledge 5th ed. (APM - Association for Project Management (UK))

- ICB v3 (IPMA Competence Baseline)

- RBC v1.1 (ABGP Competence Baseline)

- PRINCE2 (PRojects IN a Controlled Environment)

- P2M (A guidebook of Project & Program Management for Enterprise Innovation, Japanese third-generation project management method)(Download page for P2M and related products)

- V-Modell (German project management method)

- HERMES method (The Swiss general project management method, selected for use in Luxembourg and international organisations)

- Organizational Project Management Maturity Model (OPM3)

- International Standards Organization Founded 1947

- JPACE (Justify, Plan, Activate, Control, and End - The James Martin Method for Managing Projects (1981-present))

- Software Engineering Institute: Capability Maturity Model

- Total Cost Management Framework (AACE International's process for Portfolio, Program and Project Management) (ref:Cost Engineering)

Professional certifications

- CompTIA Project+, ([Computer Technology Industry Association])

- CPM (The International Association of Project & Program Management)

- IPMA (Levels of Certification: IPMA-A, IPMA-B, IPMA-C and IPMA-D)

- PMP (Project Management Professional), CAPM (Certified Associate in Project Management). PMI certifications

- Master Project Manager, Certified International Project Manager. AApM certifications

- Certified Portfolio, Program & Project Manager (C3PM)- AACE International.

- Master's Certificate in Project Management - The George Washington University and ESI International[1]

See also: An exhaustive list of standards (maturity models)

See also

{{Top}} may refer to:

- {{Collapse top}}

- {{Archive top}}

- {{Hidden archive top}}

- {{Afd top}}

- {{Discussion top}}

- {{Tfd top}}

- {{Top icon}}

- {{Top text}}

- {{Cfd top}}

- {{Rfd top}}

- {{Skip to top}}

{{Template disambiguation}} should never be transcluded in the main namespace.

- Architectural engineering

- Association for Project Management

- Capability Maturity Model

- Commonware

- Construction management

- Construction software

- Cost overrun

- Cost engineering

- Critical chain

- Deliverable

- Dependency Structure Matrix

- Earned value management

- Event chain methodology

- Flexible project management

- Functionality, mission and scope creep

- Gantt chart

- Governance

- Human Interaction Management

| class="col-break " |

- List of project management topics

- Megaprojects

- M.S.P.M.

- Optimism bias

- Planning fallacy

- Portfolio management

- Project accounting

- Project governance

- Program management

- Project management software (List of project management software)

- Project workforce management

- Process architecture

- RACI diagram

- Reference class forecasting

- Six Sigma

- Software project management

- Terms of reference

- The Mythical Man-Month

- Timesheet

- Total cost management

- Work Breakdown Structure

- Resource Leveling

References

Literature

- Berkun, Scott (2005). Art of Project Management. Cambridge, MA: O'Reilly Media. ISBN 0-596-00786-8.

- Brooks, Fred (1995). The Mythical Man-Month (20th Anniversary Edition ed.). Adison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-83595-9.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Comninos D &, Frigenti E (2002). The Practice of Project Management - a guide to the business-focused approach. Kogan Page. ISBN 0-7494-3694-8

- Flyvbjerg, Bent, (2006). "From Nobel Prize to Project Management: Getting Risks Right." Project Management Journal, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 5-15.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|id=at position 19 (help) - Heerkens, Gary (2001). Project Management (The Briefcase Book Series). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-137952-5.

- Kerzner, Harold (2003). Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling (8th Ed. ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-22577-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Chamoun, Yamal (2006). Professional Project Management, THE GUIDE (1st.Edition ed.). Monterrey, NL MEXICO: McGraw Hill. ISBN 970-10-5922-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Lewis, James (2002). Fundamentals of Project Management (2nd ed. ed.). American Management Association. ISBN 0-8144-7132-3.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Meredith, Jack R. and Mantel, Samuel J. (2002). Project Management : A Managerial Approach (5th ed. ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-07323-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Project Management Institute (2003). A Guide To The Project Management Body Of Knowledge (3rd ed. ed.). Project Management Institute. ISBN 1-930699-45-X.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Stellman, Andrew and Greene, Jennifer (2005). Applied Software Project Management. Cambridge, MA: O'Reilly Media. ISBN 0-596-00948-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Thayer, Richard H. and Yourdon, Edward (2000). Software Engineering Project Management (2nd Ed. ed.). Wiley-IEEE Computer Society Press. ISBN 0-8186-8000-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Whitty, S. Jonathan (2005). A Memetic Paradigm of Project Management (PDF). International Journal of Project Management, 23 (8) 575-583.

- Whitty, S.J. and Schulz, M.F. (2007). The impact of Puritan ideology on aspects of project management (PDF). International Journal of Project Management, 25 (1) 10-20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pettee, Stephen R. (2005). As-builts – Problems & Proposed Solutions (PDF). Construction Management Association of America.

- Verzuh, Eric (2005). The Fast Forward MBA in Project Management (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-69284-0 (pbk.).

External links

- The Project Management Institute

- AACE International

- For a more comprehensive discussion on the history of project management see Template:PDFlink,Weaver, P. 2007

- A more people-oriented explanation of Project management can be found at "Learn Project Management In 15 Minutes"

- Five Lessons Project Management