Béla Bartók: Difference between revisions

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

In 1908, inspired by both their own interest in folk music and by the contemporary resurgence of interest in traditional national culture, he and Kodály undertook an expedition into the countryside to collect and research old [[Hungarian people|Magyar]] folk melodies. Their findings came as somewhat of a surprise: previously, most people had considered real Magyar folk music to be [[Roma people|Gypsy]] music. The classic example of this misperception is [[Franz Liszt]]'s famous ''[[Hungarian Rhapsodies]]'' for piano, which were actually based on popular art-songs performed by Gypsy bands of the time. |

In 1908, inspired by both their own interest in folk music and by the contemporary resurgence of interest in traditional national culture, he and Kodály undertook an expedition into the countryside to collect and research old [[Hungarian people|Magyar]] folk melodies. Their findings came as somewhat of a surprise: previously, most people had considered real Magyar folk music to be [[Roma people|Gypsy]] music. The classic example of this misperception is [[Franz Liszt]]'s famous ''[[Hungarian Rhapsodies]]'' for piano, which were actually based on popular art-songs performed by Gypsy bands of the time. |

||

In contrast, the old Magyar folk melodies discovered by Bartók and Kodály bore little if any resemblance to the popular music |

In contrast, the old Magyar folk melodies discovered by Bartók and Kodály bore little if any resemblance to the popular music performed by these Gypsy bands. Instead, many of the folk-songs they found to be based on [[pentatonic]] scales similar to those in various Oriental folk traditions, notably those of [[Central Asia]] and [[Siberia]]. (Indeed, Kodály later discovered striking parallels between some ancient Magyar songs and songs of the [[Mari people|Mari]] and [[Chuvash people|Chuvash]] peoples of western [[Siberia]].) |

||

Bartók and Kodály quickly set about incorporating elements of this real Magyar peasant music into their compositions. While Kodály frequently quoted folk songs verbatim and wrote pieces derived entirely from authentic folk melodies, Bartók's style was more of a synthesis of folk music, classicism, and modernism. He rarely used actual peasant melodies in his compositions, but his melodic and harmonic sense was still profoundly influenced by the folk music of Hungary |

Bartók and Kodály quickly set about incorporating elements of this real Magyar peasant music into their compositions. While Kodály frequently quoted folk songs verbatim and wrote pieces derived entirely from authentic folk melodies, Bartók's style was more of a synthesis of folk music, classicism, and modernism. He rarely used actual peasant melodies in his compositions, but his melodic and harmonic sense was still profoundly influenced by the folk music of Hungary as well as that of many other nations and he was especially fond of the asymmetrical dance rhythms and pungent harmonies found in [[Bulgarian music]]. |

||

==Middle years and career== |

==Middle years and career== |

||

Revision as of 04:49, 3 April 2008

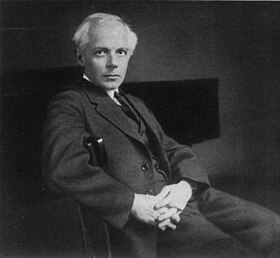

Béla Viktor János Bartók (March 25 1881 – September 26 1945) was a Hungarian composer, pianist and collector of folk music. He is considered one of the greatest composers of the 20th century and was also one of the founders of the field of ethnomusicology, through his analytical study and ethnography of folk music.

Childhood and early years

Béla Bartók was born in the small Banatian town of Nagyszentmiklós in Austria-Hungary (now Sânnicolau Mare, Romania). He displayed notable musical talent very early in life: according to his mother, he could distinguish between different dance rhythms that she played on the piano even before he learned to speak in complete sentences (Gillies 1990, 6). By the age of four, he was able to play 40 songs on the piano, and his mother began formally teaching him the next year.

Béla was a small and sickly child, and suffered from a painful chronic rash until the age of five (Gillies 1990, 5). In 1888, when he was seven, his father (the director of an agricultural school) died suddenly, and Béla's mother then took him and his sister Erzsebet to live in Nagyszőlős (today Vinogradiv, Ukraine), and then to Pozsony (today Bratislava, Slovakia). In Pressburg (Pozsony) Béla gave his first public recital at age eleven to a warm critical reception. Among the pieces he played was his own first composition, written two years previously: a short piece called "The Course of the Danube" (de Toth 1999). Shortly thereafter he was accepted as a student of László Erkel.

Early musical career

He studied piano under István Thoman (a former student of Franz Liszt) and composition under János Koessler at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest from 1899 to 1903. There he met Zoltán Kodály, who influenced him greatly and become his lifelong friend and colleague. In 1903, Bartók wrote his first major orchestral work, Kossuth, a symphonic poem which honored Lajos Kossuth, hero of the Hungarian revolution of 1848.

It was the music of Richard Strauss, whom he met at the Budapest premiere of Also sprach Zarathustra in 1902, that had the most influence on his early work. From 1907 his music also began to be influenced by the music of Claude Debussy that Kodály had brought back from Paris. His large scale orchestral works were still in the manner of Johannes Brahms or Richard Strauss, but also around this time he wrote a number of small piano pieces which show his growing interest in folk music. Probably the first piece to show clear signs of this new interest is the String Quartet No. 1 in A minor (1908), which has a few folk-like elements in it.

In 1908, inspired by both their own interest in folk music and by the contemporary resurgence of interest in traditional national culture, he and Kodály undertook an expedition into the countryside to collect and research old Magyar folk melodies. Their findings came as somewhat of a surprise: previously, most people had considered real Magyar folk music to be Gypsy music. The classic example of this misperception is Franz Liszt's famous Hungarian Rhapsodies for piano, which were actually based on popular art-songs performed by Gypsy bands of the time.

In contrast, the old Magyar folk melodies discovered by Bartók and Kodály bore little if any resemblance to the popular music performed by these Gypsy bands. Instead, many of the folk-songs they found to be based on pentatonic scales similar to those in various Oriental folk traditions, notably those of Central Asia and Siberia. (Indeed, Kodály later discovered striking parallels between some ancient Magyar songs and songs of the Mari and Chuvash peoples of western Siberia.)

Bartók and Kodály quickly set about incorporating elements of this real Magyar peasant music into their compositions. While Kodály frequently quoted folk songs verbatim and wrote pieces derived entirely from authentic folk melodies, Bartók's style was more of a synthesis of folk music, classicism, and modernism. He rarely used actual peasant melodies in his compositions, but his melodic and harmonic sense was still profoundly influenced by the folk music of Hungary as well as that of many other nations and he was especially fond of the asymmetrical dance rhythms and pungent harmonies found in Bulgarian music.

Middle years and career

In 1909, Bartók married Márta Ziegler. Their son, Béla II, was born in 1910. In 1911, Bartók wrote what was to be his only opera, Bluebeard's Castle, dedicated to his wife, Márta. He entered it for a prize awarded by the Hungarian Fine Arts Commission, which rejected it out of hand as un-stageworthy (Leafstedt 1999[citation needed]). In 1917 Bartók revised the score in preparation for the 1918 première, rewriting the ending. Following the 1919 revolution, he was pressured by the government to remove the name of the blacklisted librettist Béla Balázs (by then a refugee in Vienna) from the opera[citation needed]; it received only one revival (1936) before he emigrated. For the remainder of his life, although he was passionately devoted to Hungary, its people and culture, he never felt much loyalty to its government or official establishments.

After his disappointment over the Fine Arts Commission prize, Bartók wrote very little for two or three years, preferring to concentrate on collecting and arranging folk music. He collected in the first place in the Carpathian Basin (the then Kingdom of Hungary), this included Hungarian, Slovakian, Romanian and Bulgarian folk music. He also collected in Moldavia, Wallachia and in 1913 in Algeria and in 1936 in Turkey. However, the outbreak of World War I forced him to stop these expeditions, and he returned to composing, writing the ballet The Wooden Prince in 1914–16 and the String Quartet No. 2 in 1915–17, both influenced by Debussy. It was The Wooden Prince which gave him some degree of international fame.

Raised as a Roman Catholic, Bartók had by his early adulthood become an atheist, and considered the existence of God as undecidable and unnecessary. He later became attracted to Unitarianism, and publicly converted to the Unitarian faith in 1916. His son later became president of the Hungarian Unitarian Church (Hughes 1999–2007).

He subsequently worked on another ballet, The Miraculous Mandarin influenced by Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, as well as Richard Strauss, following this up with his two violin sonatas (written in 1921 and 1922 respectively) which are harmonically and structurally some of the most complex pieces he wrote. The Miraculous Mandarin was started in 1918, but not performed until 1926 because of its sexual content, a sordid modern story of prostitution, robbery, and murder. He wrote his third and fourth string quartets in 1927–28, after which he finally found his true voice, starting broadly incorporating folk music in his compositions. Notable examples of this period are Divertimento for strings (1939) and Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936). The String Quartet No. 5 (1934) is written in somewhat more traditional style. Bartók wrote his sixth and last string quartet in 1939.

Bartók divorced Márta in 1923, and married a piano student, Ditta Pásztory. His second son, Péter, was born in 1924.

World War II and last years

In 1940, as the European political situation worsened after the outbreak of World War II, Bartók was increasingly tempted to flee Hungary.

Bartók was strongly opposed to the Nazis and their Hungarian imitators. After they came into power in Germany, he refused to give concerts there and switched away from his German publisher. His liberal views caused him a great deal of trouble from conservatives in Hungary.

Having first sent his manuscripts out of the country, Bartók reluctantly emigrated to the U.S. with Ditta Pásztory, settling in New York City. Péter Bartók joined them in 1942 and later enlisted in the United States Navy. Béla Bartók, Jr. remained in Hungary.

Bartók never became fully comfortable in the U.S. and initially found it difficult to compose. Although well-known in America as a pianist, ethnomusicologist, and teacher, he was not well known as a composer, and there was little interest in his music during his final years. He and his wife Ditta gave concerts, and for several years, supported by a research grant, they worked on a large collection of Yugoslav folk songs. Bartók's difficulties during his first years in the US were mitigated by publication royalties, teaching, and performance tours. While their finances were always precarious, it is a myth that he lived and died in poverty and neglect. There were enough supporters to see to it that there was enough money and work available for him to live on. A proud man, Bartók generally refused outright charity. Though he was not a member of ASCAP, the society paid for any medical care he needed in his last two years and Bartók accepted this.

The first symptoms of his leukemia began in 1940, his right shoulder began to show signs of stiffening. In 1942 these symptoms increased and he started having bouts of fever. Medical examinations failed to diagnose the disease. Finally, in April 1944, he was diagnosed with leukemia but, by this time, little could be done. Even as his body was wasting away, Bartók's compositional energy reawakened one last time, and he produced a final set of masterpieces, partly thanks to the violinist Joseph Szigeti and the conductor Fritz Reiner (who had been Bartók's friend and champion since his days as Bartók's student at the Royal Academy). Bartók's last work might well have been the String Quartet No. 6, were it not for Serge Koussevitsky commissioning him to write the Concerto for Orchestra for Koussevitsky's Boston Symphony Orchestra, which premièred the work in December 1944 to overwhelming and glowing reviews. This quickly became Bartók's most popular work, although he did not live to see its full impact. He was also commissioned in 1944 by Yehudi Menuhin to write a Sonata for Solo Violin. Bartók went on in 1945 to write his Piano Concerto No. 3, a graceful and almost neo-classical work, and begin work on his Viola Concerto.

Bartók died in New York from leukemia (specifically, of secondary polycythemia) on September 26 1945 at age 64. He left the viola and third piano concertos unfinished at his death, which were later completed by his pupil, Tibor Serly. The viola piece was made from rough notes left by Bartők and never really accepted as a full work. It was revised and polished in the 1990s by Peter Bartók and is considered to be a bit closer to what Bartók may have intended.

Bartok's body was initially interred in Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York, but during the final year of communist Hungary in the late 1980s, his remains were transferred to Budapest, Hungary for a state funeral on July 7 1988 with interment in Budapest's Farkasréti Cemetery.

There is a statue of Béla Bartók in Brussels, Belgium near the central train station in a public square, Spanjeplein-Place d'Espagne, and another in London, opposite South Kensington Underground Station. There is a third statue in front of one of the houses (now a museum) that Bartók owned in the hills above Budapest.

Teaching

In 1907, Bartók began teaching as a piano professor at the Royal Academy. This position freed him from touring Europe as a pianist and enabled him to stay in Hungary. Among his notable students were Fritz Reiner, Sir Georg Solti, György Sándor, Ernő Balogh, Lili Kraus, and, after Bartók moved to the United States, Jack Beeson and Violet Archer.

Bartók also made a lasting contribution to the literature for younger students: for his son Péter's music lessons, he composed Mikrokosmos, a six-volume collection of graded piano pieces. It remains popular with piano teachers today.

Music

Paul Wilson lists as the most prominent characteristics of Bartók's music from late 1920s onwards the influence of the Carpathian basin and European art music, and his changing attitude toward (and use of) tonality, but without the use of the traditional harmonic functions associated with major and minor scales (Wilson 1992, 2-4).

Bartók is an influential modernist and his music used or may be analysed as containing various modernist techniques such as atonality, bitonality, attenuated harmonic function, polymodal chromaticism, projected sets, privileged patterns, and large set types used as source sets such as the equal tempered twelve tone aggregate, octatonic scale (and alpha chord), the diatonic and heptatonia seconda seven-note scales, and less often the whole tone scale and the primary pentatonic collection (Wilson 1992, 24-29).

He rarely used the simple aggregate actively to shape musical structure, though there are notable examples such as the second theme from the first movement of his Second Violin Concerto, commenting that he "wanted to show Schoenberg that one can use all twelve tones and still remain tonal" (Gillies 1990, 185). More thoroughly, in the first eight measures of the last movement of his Second Quartet, all notes gradually gather with the twelfth (G♭) sounding for the first time on the last beat of measure 8, marking the end of the first section. The aggregate is partitioned in the opening of the Third String Quartet with C♯-D-D♯-E in the accompaniment (strings) while the remaining pitch classes are used in the melody (violin 1) and more often as 7-35 (diatonic or "white-key" collection) and 5-35 (pentatonic or "black-key" collection) such as in no. 6 of the Eight Improvisations. There, the primary theme is on the black keys in the left hand, while the right accompanies with triads from the white keys. In measures 50-51 in the third movement of the Fourth Quartet, the first violin and 'cello play black-key chords, while the second violin and viola play stepwise diatonic lines (Wilson 1992, 25). On the other hand, from as early as the Suite for piano, op. 14 (1914), he occasionally employed a form of serialism based on compound interval cycles, some of which are maximally distributed, multi-aggregate cycles (Gollin 2007).

Ernő Lendvai (1971) analyses Bartók's works as being based on two opposing systems, that of the golden section and the acoustic scale, and tonally on the axis system (Wilson 1992, 7).

Milton Babbitt, in his 1949 critique of Bartók's string quartets, criticized Bartók for using tonality and non tonal methods unique to each piece. Babbitt noted that "Bartók's solution was a specific one, it cannot be duplicated" (Babbitt 1949, 385). Bartók's use of "two organizational principles"—tonality for large scale relationships and the piece-specific method for moment to moment thematic elements—was a problem for Babbitt, who worried that the "highly attenuated tonality" requires extreme non-harmonic methods to create a feeling of closure (Babbitt 1949, 377–78).

The cataloguing of Bartók's works is somewhat complex. Bartók assigned opus numbers to his works three times, the last of these series ending with the Improvisations Op. 20 in 1920. He ended this practice because of the difficulty of distinguising between original works and ethnographic arrangements, and between major and minor works. Since his death, two full and one partial attempts at cataloguing have been made. The first, and still most widely used, is András Szöllősy's chronological Sz. numbers, from 1 to 121. Denijs Dille subsequently reorganised the juvenilia (Sz. 1-25) thematically, as DD numbers 1 to 77. The most recent catalogue is that of László Somfai; this is a chronological index with works identified by BB numbers 1 to 129, incorporating corrections based on the Béla Bartók Thematic Catalogue (Somfai [undated][citation needed]).

One characteristic style of music is his Night music, which he used mostly in slow movements of multi-movement ensemble or orchestra compositions in his mature period. It is characterised by "eerie dissonances providing a backdrop to sounds of nature and lonely melodies" (Schneider 2006, 84). The third movementof his Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (Adagio) features in the suspense movie The Shining and is a clear example of Night music style.

Media

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

See also

Notes

Bibliography

- Babbitt, Milton (1949). "The String Quartets of Bartók". Musical Quarterly 35 (July): 377-85 [1]

- de Toth, June. 1999. "Béla Bartók: A Biography". Liner notes to Béla Bartók: Complete Piano Works 7-CD set, Eroica Classical Recordings[citation needed] [2]

- Gillies, Malcolm (ed.). 1990. Bartók Remembered. London: Faber. ISBN 0571142435 (cased) ISBN 0571142443 (pbk)

- Gillies, Malcolm. "Béla Bartók", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed May 23, 2006), (subscription access)

- Gollin, Edward. 2007. "Multi-Aggregate Cycles and Multi-Aggregate Serial Techniques in the Music of Béla Bartók". Music Theory Spectrum 29, no. 2 (Fall): 143–76.

- Hughes, Peter. 1999–2007. "Béla Bartók" in Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography. [n.p.]: Unitarian Universalist Historical Society.[3]

- Leafstedt, Carl S. 1999. Inside Bluebeard's Castle. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195109996

- Lendvai, Ernő (1971). Béla Bartók: An Analysis of His Music. London: Kahn and Averill.

- Somfai, László. [undated]. "The 'BB' Numbering System", in "Mikrocosmos" [sic], ed. by Zoltán Kocsis, Philips 462 381-2.[citation needed]

- Schneider, David E. 2006. Bartók, Hungary, and the Renewal of Tradition: Case Studies in the Intersection of Modernity and Nationality. California Studies in 20th-Century Music 5. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520245037

- Wilson, Paul (1992). The Music of Béla Bartók. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300051115.

Further reading

- Antokoletz, Elliott (1984). The Music of Béla Bartók: A Study of Tonality and Progression in Twentieth-Century Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0520046048

- Chalmers, Kenneth (1995). Bela Bartok. London: Phaidon.

- Kárpáti, János (1975). Bartók's String Quartets. Translated by Fred MacNicol. Budapest: Corvina Press.

- Somfai, László. 1981. Tizennyolc Bartók-tanulmány [Eighteen Bartók Studies]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó. ISBN 9633303702

- Somfai, Lászlo. 1996. Béla Bartók: Composition, Concepts, and Autograph Sources. Ernest Bloch Lectures. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520084853

External links

- Bartók Béla Memorial House, Budapest

- Bartók Béla Guitar transliteration videos

- Free scores by Bartók at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Bartók and his relationship with Unitarianism

- A Genius on the IRT - Béla Bartók in New York review of Agatha Fassett’s chronicle of the last years of Bartók’s life

- Classical Cat page of Bartók links

- Gallery of Bartók portraits

- Bartók's Percussion Repertoire, from Bell Percussion's Composer Repertoire resource]

Recordings

- Kunst der Fuge: Béla Bartók - MIDI files

- Contrasts: Verbunkos (7.10 mb), Contrasts: Piheno (5.86 mb), Contrasts: Sebes (8.26 mb). Helen Kim (violin), Ted Gurch (clarinet), Adam Bowles (piano). From Luna Nova New Music Ensemble