Lectionary: Difference between revisions

qeryana link added |

|||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

===Other lectionary information=== |

===Other lectionary information=== |

||

The Lectionary provides shorter readings: |

|||

*A reading from the [[Old Testament]] or the [[Epistles]] |

*A reading from the [[Old Testament]] or the [[Epistles]] |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

*A reading from one of the [[Gospel]]s. |

*A reading from one of the [[Gospel]]s. |

||

These readings are generally rather short, and encompass only a about 1/5 of all of the Bible's verses. |

|||

These readings are generally much shorter than the weekend readings. The pericopes for the first reading along with the psalms are arranged in a 2-year cycle. The Gospels are arranged so that all four are read in their entirety every year. |

|||

In some churches, the Lectionary is carried in the entrance procession by a [[lector]]. In the Roman Catholic Church, it is prohibited to process with the Lectionary, but a [[Gospel Book]] may be carried by a [[deacon]] or instituted lector. When a Gospel Book is used, the first three readings are read from the Lectionary, while the Gospel Book is used for the final reading. |

In some churches, the Lectionary is carried in the entrance procession by a [[lector]]. In the Roman Catholic Church, it is prohibited to process with the Lectionary, but a [[Gospel Book]] may be carried by a [[deacon]] or instituted lector. When a Gospel Book is used, the first three readings are read from the Lectionary, while the Gospel Book is used for the final reading. |

||

Revision as of 21:18, 9 August 2008

A Lectionary is a book or listing that contains a collection of scripture readings appointed for Christian or Judaic worship on a given day or occasion.

History

In antiquity the Jews created a schedule of scripture readings assigned to be read in the synagogue. Selections were read from the Torah and the haftorah. Jesus likely read one of these pre-assigned readings when he read from Isaiah 61:1–2, as recorded in Luke 4:16–21, when he inaugurated his public ministry. The early Christians adopted the Jewish custom of reading extracts from the Old Testament on the sabbath. They soon added extracts from the writings of the Apostles and Evangelists.[1]

Both Hebrew and Christian lectionaries developed over the centuries. Typically, a lectionary will go through the scriptures in a logical pattern, and also include selections which were chosen by the religious community for their appropriateness to particular occasions.

The use of pre-assigned, scheduled readings from the scriptures can be traced back to the early church. Not all of the Christian Church used the same lectionary, and throughout history, many varying lectionaries have been used in different parts of the Christian world. Until the Second Vatican Council, most Western Christians (Roman Catholics, Old Catholics, Anglicans, Lutherans, and those Methodists who employed the lectionary of Wesley) used a lectionary that repeated on a one-year basis. This annual lectionary provided readings for Sundays and, in those Churches that celebrated the festivals of saints, feast-day readings. The Eastern Orthodox Church and many of the Oriental Churches continue to use an annual lectionary.

Lectionaries from before the invention of the [printing press] contribute to understanding the textual history of the Bible. See also List of New Testament lectionaries.

Western Lectionaries

Roman Lectionary and the Revised Common Lectionary

The roots and history of the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL) and the Roman Catholic Lectionary originated in the Roman Catholic Church, where it generally goes by the Latin name Ordo Lectionum Missae.

Since the Second Vatican Council of 1962–1965, the revised lectionary of the Roman Catholic Church has been a foundation-block upon which many contemporary lectionaries have been based, most notably the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL), and its derivatives, as organized by the Consultation on Common Texts (CCT) organization located in Nashville, Tennessee. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and many traditional mainline American Protestant denominations are members. The CCT thereby represents the majority of American Christians.

Most of the current lectionaries used by western Christian denominations organize the scripture passages to be read in worship services for each week of the year. The listing for a given week includes:

- A reading from the Old Testament;

- A responsorial Psalm;

- A reading from one of the Epistles;

- A reading from one of the Gospels.

3 year cycle

The Lectionary (both Roman and RCL versions) is organized into a three-year cycle of readings. The reading cycle is denoted by letter as A, B, or C. The year A cycle begins at the Advent and Christmas near the end of those years whose number is evenly divisible by 3, e.g., 2001, 2004, 2007. Year B follows year A, and year C follows year B.

- Year A: Most Gospel readings from the Gospel of Matthew.

- Year B: Most Gospel readings from the Gospel of Mark.

- Year C: Most Gospel readings from the Gospel of Luke.

The Gospel of John is always read for Easter, and is used for other liturgical seasons including Advent, Christmas, and Lent where appropriate.

There is also a 2 year cycle for the weekday readings (year 1 and year 2).

Other lectionary information

The Lectionary provides shorter readings:

- A reading from the Old Testament or the Epistles

- A responsorial Psalm;

- A reading from one of the Gospels.

These readings are generally rather short, and encompass only a about 1/5 of all of the Bible's verses.

In some churches, the Lectionary is carried in the entrance procession by a lector. In the Roman Catholic Church, it is prohibited to process with the Lectionary, but a Gospel Book may be carried by a deacon or instituted lector. When a Gospel Book is used, the first three readings are read from the Lectionary, while the Gospel Book is used for the final reading.

The Lectionary is not to be confused with a missal, gradual or sacramentary. While the Lectionary contains scripture readings, the missal or sacramentary contains the appropriate prayers for the service, and the gradual contains chants for use on any particular day. In particular, the gradual contains a responsory which may be used in place of the responsorial psalm.

Eastern Lectionaries

In the Eastern Churches (Eastern Catholic—i.e., those united with Rome—Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, the Assyrian Church of the East, and those bodies not in communion with any of them but still practicing eastern liturgical customs) tend to retain the use of a one-year lectionary in their liturgy. Different churches follow different liturgical calendars (to an extent). Most Eastern Lectionaries provide for an Epistle and a Gospel to be read on each day.

Byzantine lectionary

Those churches (Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic) which follow the Rite of Constantinople, provide an Epistle and Gospel reading for most days of the year, to be read at the Divine Liturgy; however, during Great Lent there is no celebration of the Liturgy on weekdays (Monday through Friday), so no Epistle and Gospel are appointed for those days. As a historical note, the Greek lectionaries are a primary source for the Byzantine text-type used in the scholarly field of textual criticism.

Epistle and Gospel

The Gospel readings are found in a Gospel Book (Evangélion) and an Epistle Book (Apostól). There are differences in the precise arrangement of these books between the various national churches. In the Hellenic (Greek Orthodox) practice, the readings are in the form of pericopes (selections from scripture containing only the portion actually chanted during the service), and are arranged according to the order in which they occur in the church year, beginning with the Sunday of Pascha (Easter), and continuing throughout the entire year, concluding with Holy Week. Then follows a section of readings for the commemorations of Saints and readings for special occasions (Baptism, Funeral, etc.). In the Slavic practice, the biblical books are reproduced in their entirety and arranged in the canonical order in which they appear in the Bible.

The annual cycle of the Gospels is composed of four series:

- The Gospel of St. John

- read from Pascha until Pentecost Sunday

- The Gospel of St. Matthew

- divided over seventeen weeks beginning with the Monday of the Holy Spirit (the day after Pentecost). From the twelfth week, it is read on Saturdays and Sundays while the Gospel of St. Mark is read on the remaining weekdays

- The Gospel of St. Luke

- divided over nineteen weeks beginning on the Monday after the Elevation of the Holy Cross. From the thirteenth week, it is only read on Saturdays and Sundays, while St. Mark's Gospel is read on the remaining weekdays

- The Gospel of St. Mark

- read during the Lenten period on Saturdays and Sundays — with the exception of the Sunday of Orthodoxy.

The interruption of the reading of the Gospel of Matthew after the Elevation of the Holy Cross is known as the "Lukan Jump" The jump occurs only in the Gospel readings, there is no corresponding jump in the Epistle. From this point on the Epistle and Gospel readings do not exactly correspond, the Epistles continuing to be determined according to the moveable Paschal cycle and the Gospels being influenced by the fixed cycle.

The Lukan Jump is related to the chronological proximity of the Elevation of the Cross to the Conception of the Forerunner (St. John the Baptist), celebrated on September 23rd. In late Antiquity, this feast marked the beginning of the ecclesiastical New Year. Thus, beginning the reading of the Lukan Gospel toward the middle of September can be understood. The reasoning is theological, and is based on a vision of Salvation History: the Conception of the Forerunner constitutes the first step of the New Economy, as mentioned in the stikhera of the matins of this feast. The Evangelist Luke is the only one to mention this Conception (Luke 1:5–24).

In Russia, the use of the Lukan Jump vanished; however in recent decades, the Russian Church has begun the process of returning to the use of the Lukan Jump.

Old Testament Readings

Other Services have scriptural readings also. There is a Gospel lesson at Matins on Sundays and feast days. These are found in the Evangelion. There are also readings from the Old Testament, called "parables" (Paroemia), which are read at Vespers on feast days. These parables are found in the Menaion, Triodion or Pentecostarion. During Great Lent, parables are read every day at Vespers and at the Sixth Hour. These parables are found in the Triodion.

Syriac Orthodox

In the Syriac Orthodox Church, the lectionary begins with the liturgical calendar year on Qudosh `Idto (the Sanctification of the Church), which falls on the eighth Sunday before Christmas. Both the Old and the New Testament books are read except the books of Revelation, Song of Solomon, and I and II Maccabees. Scripture readings are assigned for Sundays and feast days, for each day of Lent and Holy Week, for raising people to various offices of the Church, for the blessing of Holy Oil and various services such as baptisms and funerals.

Generally, three Old Testament lections, a selection from the prophets, and three readings from the New Testament are prescribed for each Sunday and Feast day. The New Testament readings include a reading from Acts, another from the Catholic Epistles or the Pauline Epistles, and a third reading from one of the Gospels. During Christmas and Easter a fourth lesson is added for the evening service. The readings reach a climax with the approach of the week of the Crucifixion. Through Lent lessons are recited twice a day except Saturdays. During the Passion Week readings are assigned for each of the major canonical hours.

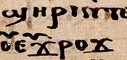

Extra-Christian usage theory

As per theory expressed in The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran: A Contribution to the Decoding of the Language of the Koran English Edition of 2007 (Die syro-aramäische Lesart des Koran: Ein Beitrag zur Entschlüsselung der Koransprache, 2000), a book by German philologist and professor of ancient Semitic and Arabic languages Christoph Luxenberg[2] which takes a philological and text-critical approach to the study of the Qur'an and is considered a major, but controversial work in the field of Qur'anic philology, the word Qur'an itself is derived from 'qeryana', a Syriac term from the Christian liturgy that means ‘lectionary’ a book of liturgical readings. The book being a Syro-Aramaic lectionary, with hymns and Biblical extracts, created for use in Christian services. This lectionary was translated into Arabic as a missionary effort. It was not meant to start a new religion, but to spread an older one. [3]

References

- ^ "Lectionary". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- ^ The Virgins and the Grapes: the Christian Origins of the Koran

- ^ Giving the Koran a history:

See also

- Revised Common Lectionary

- Mass (liturgy)

- Liturgical year

- Gospel Book

- Ekphonetic notation

- Lector

- Pericope

- Lection

- The Text This Week

- Book of Alternative Services

External links

- The Revised Common Lectionary

- The Roman Catholic Lectionary

- General Introduction to the Lectionary (Roman Catholic)

- Lectionary of the Byzantine (Eastern Orthodox) Church

- LectionaryLite Lectionary criticism website

- John Shearman's Liberal Lectionary

- The "Lukan Jump" Orthodox Research Institute

- Orthodox Christian Lectionary Explained (Russian Orthodox)

- Lectionary of the Syriac Orthodox Church

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Lectionary Central For the study and use of the traditional Western Eucharistic lectionary.