Sorbs: Difference between revisions

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

First Lusatian cities were captured in April 1945, when [[the Red Army]] with the [[Polish Second Army]] crossed the river [[Kwisa|Queis]] (pol:Kwisa). Defeating [[Nazi Germany]] changed the Sorbs’ situation considerably: those to the east of Neisse and Oder were expelled or assimilated by Poland{{Fact|date=April 2008}}. The regions in [[East Germany]] (the German Democratic Republic) faced a large influx of [[Expulsion of Germans after World War II|expelled Germans]] and heavy industrialisation, which both forced [[Germanization]]. The East German authorities tried to counteract this development by creating a broad range of Sorbian institutions. The Sorbs were officially recognized as an ethnic minority, more than 100 Sorbian schools and several academic institutions were founded, the Domowina and its associated societies were reestablished and a Sorbian theatre was created. Owing to the oppression of the church and forced collectivization, however, these efforts were severely affected and consequently over time the number of people speaking Sorbian languages decreased by half. |

First Lusatian cities were captured in April 1945, when [[the Red Army]] with the [[Polish Second Army]] crossed the river [[Kwisa|Queis]] (pol:Kwisa). Defeating [[Nazi Germany]] changed the Sorbs’ situation considerably: those to the east of Neisse and Oder were expelled or assimilated by Poland{{Fact|date=April 2008}}. The regions in [[East Germany]] (the German Democratic Republic) faced a large influx of [[Expulsion of Germans after World War II|expelled Germans]] and heavy industrialisation, which both forced [[Germanization]]. The East German authorities tried to counteract this development by creating a broad range of Sorbian institutions. The Sorbs were officially recognized as an ethnic minority, more than 100 Sorbian schools and several academic institutions were founded, the Domowina and its associated societies were reestablished and a Sorbian theatre was created. Owing to the oppression of the church and forced collectivization, however, these efforts were severely affected and consequently over time the number of people speaking Sorbian languages decreased by half. |

||

Sorbian Slovians caused the communistic government of the [[GDR]] (the German Democratic Republic) plenty of trouble, mainly because of the high levels of religiousness and resistance to the nationalizing of agriculture. During the campaign of compulsory collectivization, a great deal of unprecedented incidents were reported. Thus, throughout the [[Uprising of 1953 in East Germany]] in [[Lusatia]], violent clashes with |

Sorbian Slovians caused the communistic government of the [[GDR]] (the German Democratic Republic) plenty of trouble, mainly because of the high levels of religiousness and resistance to the nationalizing of agriculture. During the campaign of compulsory collectivization, a great deal of unprecedented incidents were reported. Thus, throughout the [[Uprising of 1953 in East Germany]] in [[Lusatia]], violent clashes with the police were reported. An open uprising took place in three upper communes of Błot. |

||

After another unification of [[Germany]], on October 3rd 1990, Lusatians made efforts for creating an autonomous administrative unit, however [[Helmut Kohl]]’s government did not agree to it. After 1989 the Sorbian movement revived, however it still does encounter many obstacles. Although [[Germany]] supports national minorities, Sorbs’ aspirations are not sufficiently fulfilled. Postulates of uniting [[Lusatia]] into one country were not taken into consideration. [[Upper Lusatia]] still belongs to [[Saxony]] and [[Lower Lusatia]] to [[Brandenburg]]. Liquidations of Sorbian schools even on the area mostly populated by Sorbs still happen, under the pretence of financial difficulties or demolition of whole villages to create quarries of lignite. |

After another unification of [[Germany]], on October 3rd 1990, Lusatians made efforts for creating an autonomous administrative unit, however [[Helmut Kohl]]’s government did not agree to it. After 1989 the Sorbian movement revived, however it still does encounter many obstacles. Although [[Germany]] supports national minorities, Sorbs’ aspirations are not sufficiently fulfilled. Postulates of uniting [[Lusatia]] into one country were not taken into consideration. [[Upper Lusatia]] still belongs to [[Saxony]] and [[Lower Lusatia]] to [[Brandenburg]]. Liquidations of Sorbian schools even on the area mostly populated by Sorbs still happen, under the pretence of financial difficulties or demolition of whole villages to create quarries of lignite. |

||

Revision as of 16:09, 25 December 2008

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 60,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Sorbian (Upper Sorbian, Lower Sorbian), German | |

| Religion | |

| Catholicism, Lutheranism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and other West Slavs | |

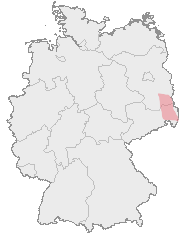

Sorbs (Template:Lang-hsb; Template:Lang-dsb) also known as Wends, Lusatian Sorbs or Lusatian Serbs, are a Slavic people settled in Lusatia, a region on the territory of Germany and Poland.

Sorbs are divided into two groups:

- Upper Sorbs, who speak Upper Sorbian (about 40,000 people).[citation needed]

- Lower Sorbs, who speak Lower Sorbian (about 20,000 people). [citation needed]

The dialects spoken vary in intelligibility in different areas.

Toponyms

The name of the nation is probably connected with the Polish word “stepson” (Polish: pasierb) and originally meant tribesman (the one who sucked milk of the same mother). The question of kinship of Balkan Serbs and Lusatian Sorbs is not accidental. According to one of the hypotheses, in the 5th century, after leaving their proto-Slavonic homeland, common ancestors of all Serbs and Sorbs divided into two groups. One of the groups (the ancestors of the Serbs), known as the White Serbs, reached the Balkans through the Carpathian Mountains under the leadership of the Unknown Archont, whilst the others settled in the middle part of the Elbe and become 'Sorbs'. The story depicted in Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos' De Administrando Imperio tells that a brother of the Archont had remained in what is today Lusatia with a part of the Serb people. It is unlikely that the name Serb developed in both of these two groups separately. The name Lusatia (German: Lausitz), originally meaning marshy ground probably derives from the Slavic word ług (grove, young forest), at the same time indicating that the regions surroundings were rich in forest. Sorbs call themselvs Serbs (Serbja, Serby), and Balkan Serbs are referred to as South Serbs. Serbs call Sorbs - Lusatian Serbs (Лужички Срби, Lužički Srbi).

Tribal division

Having settled by the Elbe, Spree and Neisse in the 6th century, Sorbian tribes divided into two main groups, which have taken their names from the characteristics of the area where they had settled. Sorbs living on the swampy broads of the Lower Spree have taken their name from the word marsh. The Milceni (ancestors of Upper Sorbs) settled on fertile soil around Upper Spree, the name derives from the word měl’ (loess soil). Both groups were separated from each other by a wide and uninhabited forest range. The rest of the tribes settled themselves between the Elbe and Saale.

History of the Sorbs

During the 6th century A.D. Sorbs arrived in the area extending between the rivers in the East: the Bober (Czech: Bobr, Polish: Bóbr), Kwisa and Oder (Polish: Odra) to rivers in the West: the Saale and Elbe. In the North, the area of their settlement reached Berlin. In 631 A.D., for the first time, the Fredegar’s Chronicle described them as Surbi. Annales Regni Francorum mentions that in 806 A.D., Miliduch (the Serbian King) fought against the Francs and was killed. In 932 Henry I conquered Lusatia and Milsko. In 933 Lusatia was again conquered by Gero II – the Margrave of the Saxon Ostmark, who in 939 cunningly murdered 30 Sorbian princes during the feast. As a result, there were many Sorbian uprisings against the Germans. From this early period there remained only a reconstructed castle- Raddusch in Lower Lusatia. During the reign of Boleslaw I of Poland (Polish: Bolesław Chrobry) in 1002-1018 A.D., three Polish-German wars were waged which caused Lusatia to come from one ruler to another. In 1018, on the strength of peace in Bautzen, Lusatia became a part of Poland; however, before 1031 it was returned to Germany. From 11th to 15th century, in Lusatian development of agriculture and intensification of colonization took place by Frankish, Flemish and Saxon settlers. In 1327 first prohibitions of using Sorbian in Altenburg, Zwickau and Leipzig appeared. Between 1376 - 1635 Lusatia again became a part of an Empire, in the rule of the Bohemian Luxembourgs (a component part of Saint Waclav’s Crown. At the beginning of 16th century the whole Sorbian tribes’ area, with the exception of Lusatia, underwent Germanization. From 1635 Lusatia became a feudality of Saxon electorates. The Thirty Years War and epidemic of the Black Death led Lusatia to terrible devastation: almost half of Sorbs died. This led to further German colonization and Germanization. In 1667 the Prince of Brandenburg, Frederick Wilhelm, ordered the immediate destruction of all Sorbian printed materials and banned saying masses in this language. At the same time the Evangelical Church supported printing Sorbian religious literature as a means of fighting with the Counterreformation. In 1706 the Sorbian Seminary, the main quarter of educating Sorbian Catholic priests, was founded in Prague. Evangelical students of theology formed the Sorbian College of Ministers.

The Congress of Vienna, in 1815, gave part of Upper Lusatia to Saxony, but most of Lusatia to Prussia. More and more bans limiting the use of Sorbian languages appeared until 1835 in Saxony and Prussia; emigration of the Sorbs mainly to Texas (to the town of Serbin) and Australia increased. In 1848, 5000 Sorbs signed the petition to the Saxon Government, in which they demanded equality of the Sorbian language with the German one in churches, courts, schools and Government departments. From 1871 the whole territory/terrain of Lusatia became a part of united Germany and was divided into three parts: Silesia, Prussia and Saxony.

From 1871 the industrialization of the region and German immigration began; official Germanization intensified. Although the Weimar Republic guaranteed constitutional minority rights, it did not practice it.

Throughout The Third Reich Sorbians were described as a German tribe and their national poet Handrij Zejler as German as well. Young Sorbians were enrolled in the Wehrmacht and sent to the front. Sorbian activists were sent to concentration camps. For instance, father Jan Čyž was a prisoner in the Dachau concentration camp, publicist Marja Grólmusec was killed in the Ravensbrück concentration camp and Alojs Andricki was murdered with an injection of phenol. Entangled lives of the Sorbs during World War II are exemplified by life story of Mina Witkojc, Měrčin Nowak-Njechorński or Jan Skala.

First Lusatian cities were captured in April 1945, when the Red Army with the Polish Second Army crossed the river Queis (pol:Kwisa). Defeating Nazi Germany changed the Sorbs’ situation considerably: those to the east of Neisse and Oder were expelled or assimilated by Poland[citation needed]. The regions in East Germany (the German Democratic Republic) faced a large influx of expelled Germans and heavy industrialisation, which both forced Germanization. The East German authorities tried to counteract this development by creating a broad range of Sorbian institutions. The Sorbs were officially recognized as an ethnic minority, more than 100 Sorbian schools and several academic institutions were founded, the Domowina and its associated societies were reestablished and a Sorbian theatre was created. Owing to the oppression of the church and forced collectivization, however, these efforts were severely affected and consequently over time the number of people speaking Sorbian languages decreased by half.

Sorbian Slovians caused the communistic government of the GDR (the German Democratic Republic) plenty of trouble, mainly because of the high levels of religiousness and resistance to the nationalizing of agriculture. During the campaign of compulsory collectivization, a great deal of unprecedented incidents were reported. Thus, throughout the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany in Lusatia, violent clashes with the police were reported. An open uprising took place in three upper communes of Błot.

After another unification of Germany, on October 3rd 1990, Lusatians made efforts for creating an autonomous administrative unit, however Helmut Kohl’s government did not agree to it. After 1989 the Sorbian movement revived, however it still does encounter many obstacles. Although Germany supports national minorities, Sorbs’ aspirations are not sufficiently fulfilled. Postulates of uniting Lusatia into one country were not taken into consideration. Upper Lusatia still belongs to Saxony and Lower Lusatia to Brandenburg. Liquidations of Sorbian schools even on the area mostly populated by Sorbs still happen, under the pretence of financial difficulties or demolition of whole villages to create quarries of lignite.

Today (2008) Sorbian institutions serving 60,000 Sorb people receive less money for preservation of their culture in face of Germanisation then one German theater's yearly budget in Berlin<[1], an annual state grant of 15.6 million Euro by the Federal and the Saxon government [2] Faced with growing threat of cultural extincton the Domowina issued a memorandum in March 2008.[3] and called for "help and protection against the growing threat of their cultural extinction, since an ongoing conflict between the German government, Saxony and Brandenburg about the financial distribution of help blocks the financing of almost all Sorbian institutions". The memorandum also demands a reorganisation of competence by ceding responsibility from the Länder to the federal government and an expanded legal status. The call has been issued to all governments and heads of state of the European Union[4].

Besides the memorandum Sorbs also called on Poland and Polish President Lech Kaczynski for protection and to represent them in talks with German state as unlike for example Danes have no state to help them against German authorities, as Jan Nuck stated "I think if Angela Merkel speaks about German minority rights in Poland to Lech Kaczynski, then Polish President should demand the same about us". Nuck also said that the rights of Sorb people are not respected in German "Federal government and land government don't respect them(rights)" [2] Further appeal has been made to Polish Embassy in Berlin starting with "Help us. Do something for us. Our culture is dying. We are dying out. Slavs should help each other". Jan Nuck says it is difficult to judge if the situation comes from indifference of officials or if it is a concentrated effort aiming against existence of Sorb national identity in Germany[1].

On May 28, 2008, the Sorbian politician Stanislaw Tillich, member of the governing Christian Democrats, was elected as Minister President of the State of Saxony.

Language and culture

The oldest known relic of Sorbian literature originated in about 1530 - Bautzen townsmen’ oath. In 1548 Mikołaj Jakubica – Lower Sorbian vicar, from the village called Lubanice, wrote the first unprinted translation of the New Testament into Lower Sorbian.

In 1574 the first Sorbian book was printed: Albin Mollers’ songbook. In 1688 Jurij Kawštyn Swětlik translated the Bible for Catholic Sorbs. In 1706-1709 the New Testament was printed in the Upper Sorbian translation was done by Michał Frencel and in Lower Sorbian by Jan Bogumił Fabricius (1681-1741). Jan Bjedrich Fryco (a.k.a.Johann Friedrich Fritze) (1747-1819), translated the Old Testament for the first time into Lower Sorbian, published in 1790.

Other Sorbian Bible translators include Jakub Buk (1825-1895), Michel Hornik (Michael Hornig) (1833-1894), Jurij Łušćanski (a.k.a. Georg Wuschanski) (1839-1905).

In 1709 for the short period of time, there was the first printed Sorbian newspaper. In 1767 Jurij Mjeń publishes the first secular Sorbian book. Between 1841 and 1843, Jan Arnošt Smoler and Leopold Haupt published two-volume collection of Wendish folk-songs in Upper and Lower Lusatia.

From 1842, the first Sorbian publishing companies started to appear: the poet Handrij Zejler set up a weekly magazine, the precursor of today’s Serbian News. In 1845 in Bautzen the first festival of Sorbian songs took place.

In 1875, Jakub Bart-Ćišinski, the poet and classicist of Upper Sorbian literature, and Karol Arnošt Muka created a movement of young Sorbians influencing Lusatian art, science and literature for the following 50 years.

Similar movement in Lower Lusatia was organized around the most prominent Lower Lusatian poets Mato Kósyk and Bogumił Šwjela.

In 1904, mainly thanks to the Sorbs’ contribution, the most important Sorbian cultural centre (the Sorbian House) was built in Bautzen. In 1912, the social and cultural organization of Lusatian Sorbs was created, the Domowina Institution - the union of Sorbian organizations. In 1919 it had 180,000 members. In 1920 Jan Skala set up a Sorbian party and in 1925 in Berlin, Skala started Kulturwille- the newspaper for the protection of national minorities in Germany. In 1920 the Sokol Movement was founded (youth movement and gymnastic organization). From 1933 the Nazi party started to repress the Sorbs. At that time the Nazi also dissolved the Sokol Movement and began to combat every sign of Sorbian culture. In 1937 activities of the Domowina Institution and other organizations were banned as anti-national. Sorbian clergymen and teachers were forcedly deported from Lusatia; The Third Reich confiscated the Sorbian House, other buildings and crops.

On May 10th, in Crostwitz, after The Red Army’s invasion, the Domowina Institution renewed its activity. In 1948 Landtag of Saxony passed an Act guaranteeing protection to Sorbian Lusatians; in 1949 Brandenburg resolved a similar law. In the times of the GDR, Sorbian organizations were financially supported by the country, but at the same time the authorities encouraged Germanization of Sorbian youth as a means of incorporating them into the system of “building Socialism”. Sorbian language and culture could only be publicly presented as long as they promoted Socialistic ideology.

For over 1000 years the Sorbs were able to maintain and even develop their national culture, despite of escalating Germanization and Polonization, mainly due to the high level of religiousness, cultivating their tradition and strong families (until now a Sorbian family often has 5 children).

In the middle of the 20th century, the revival of the Central European nations included some Sorbs, who became strong enough to twice attempt to regain their independence. After World War II, the Lusatian National Committee in Prague claimed the right to self-govern and separate from Germany and create a Lusatian Free State or be attached to Czechoslovakia. The majority of the Sorbs was organized in the Domowina though and did not intend to split from Germany. Claims asserted by Lusatian National movement were postulates of joining Lusatia to Poland or Czechoslovakia. Between 1945 – 1947 they postulated about ten memorials to the UN, the USA, the USSR, Great Britain, France, Poland and Czechoslovakia, however, it did not bring any results. On April 30th 1946, the Lusatian National Committee also postulated a proper petition to the Polish Government, signed by Paweł Cyż – the minister and an official Sorbian delegate in Poland. There was also a project of proclaiming a Lusatian Free State, whose Prime Minister was supposed to be a Polish archaeologist of Lusatian origin- Wojciech Kóčka. The most radical postulates in this area were expressed by the Lusatian youth organization- Narodny Partyzan Łužica.

Similarly, in Czechoslovakia, where before the Potsdam Conference in Prague, 300.000 people manifested for the independence of Lusatia. The endeavours to separate Lusatia from Germany did not succeed because of the individual and geopolitical interests. After 1918, David Lloyd George did not intend to impoverish Germany and Stalin, after World War II, desired to conquer the whole of Germany.

The statistics might prove the progression of Germanization among Sorbs: by the end of the 19th century, about 150,000 people spoke Sorbian languages. In 1920 almost all Sorbs mastered Sorbian and German at the same degree. The last Sorb who spoke little or no German died in Műschen village in 1954. Nowadays, in 2004, the number of people using Sorbian languages has been estimated to no more than 50,000.

Regions of Lusatia

There are 3 main regions of Lusatia that differ in the language, religion and customs.

Region of Catholic Lusatia

Catholic Lusatia encompasses 85 towns in the districts of Bautzen, Kamenz and Hoyerswerda. This is where the Upper Sorbian Language, customs and tradition are still being cultivated. In some of the places (e.g. Radibor/ Radwor, Crostwitz/Chrósćicy, and Rosenthal/Róžant) Sorbs are the majority of the population, basically only in this region one can still hear children speaking Sorbian.

On Sundays, during holidays and weddings people wear women’s (and men’s) regional costumes (children and young people wear it as well) rich in decoration, embroidery and encrusted with pearls.

There are many traditions cultivated, such as: Bird Wedding (25th of January), Easter Cavalcade of Riders, Witch Burning (30th April), Maik, singing on Saint Martin’s Day (Nicolay), celebration of Saint Barbara’s Day and Saint Nicolas’ Day.

Region of Hoyerswerda (Wojerecy) and Schleife (Slepo)

In this region (the area from Hoyerswerda to Schleife) the dialect with characteristic features of both Upper and Lower Sorbian is still in use. This is a Protestant region, highly devastated by the brown coal mining industry, sparsely populated and to a great extend Germanized (Sorbian is only used by few people over 60 years old).

The region can be distinguished by many Slavic wooden architecture monuments (churches, houses), regional costumes’ diversity (mainly worn by older women) with white knitted and black cross-like embroidery and the tradition of playing bagpipes. In several villages residents cultivate traditions such as: expelling of winter, Maik, Easter and Great Friday singing, celebrating dźěćetko (disguised child or young girl giving Christmas presents)

Region of Lower Lusatia

There are 60 towns from the area of Cottbus belonging to this region, where most of the older people (over 60), but few young people and children, can speak the Lower Sorbian language, often with many borrowings from the German language (when talking to young people, they generally use German). In the region some primary schools still teach bilingual, and in Cottbus there is an important gymnasium who still have Lower Sorbian as the main language of education. This is a Protestant region, again highly devastated by the brown coal mining industry. The biggest tourist attraction of the region (and in the whole Lusatia) are the marshlands, with many Spreewald/Błóta canals, picturesque broads of the Spree.

Regional costumes are colourful and characteristic (worn mainly by older but on holydays by young woman as well). A big, rich in golden embroidering headscarf lapa is a part of regional costume that differs in every village.

In some villages following traditions are cultivated: Shrovetide, Maik, Easter bonfires, Roosters catching/hunting. In Jänschwalde (Sorbian: Janšojcach) so called Janšojki bog (disguised young girl) gives Christmas presents.

Lusatian anthem

in Lower Sorbian

- Rědna Łužyca

- Rědna Łužyca,

- spšawna, pśijazna,

- mojich serbskich woścow kraj,

- mojich glucnych myslow raj,

- swěte su mě twoje strony.

- Cas ty pśichodny,

- zakwiś radostny!

- Och, gab muže stanuli,

- za swoj narod źěłali,

- godne nimjer wobspomnjeśa!

in Upper Sorbian

- Rjana Łužica

- Rjana Łužica,

- sprawna přećelna,

- mojich serbskich wótcow kraj,

- mojich zbóžnych sonow raj,

- swjate su mi twoje hona!

- Časo přichodny,

- zakćěj radostny!

- Ow, zo bychu z twojeho

- klina wušli mužojo,

- hódni wěčnoh wopomnjeća!

The Sorbs and Poland

One of the pioneers of the cooperation between the two nations was Polish historian Wilhelm Bogusławski who lived in the 19th century and wrote the first book on Polish-Sorbian history Rys dziejów serbołużyckich (Polish title), it was published in Saint Petersburg in 1861. The book was expanded and published again in cooperation with Michał Hórnik in 1884 in Bautzen, under a new title Historije serbskeho naroda. Alfons Parczewski was another friend of Sorbs, who from 1875 was involved in Sorbs' rights protection, participating in Sorbian meetings in Bautzen. It was thanks to him, among others, that Józef Ignacy Kraszewski founded a scholarship for Sorbian students. An association of friends of Sorbian Nation was established at the University of Warsaw in 1936 (Polish full name: Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Narodu Serbo-Łużyckiego). It gathered people not only from the university. Its president was Professor Stanisław Słoński, and the deputy president was Julia Wieleżyńska. The association was a legal entity. There were 3 individual organizations devoted to Sorbian matters. Prołuż founded in Krotoszyn, expanded to all Poland (3000 members). It was biggest noncommunist organization that dealt with foreign affairs. This youth organization was created during the soviet occupation and its motto was “Polish guard over Lusatia” (pl. Nad Łużycami polska straż). Its highest activity was in Greater Poland (Polish: Wielkopolska, a district of western Poland). After the creation of East Germany, Prołuż was dissolved, and its president historian from Poznań Alojzy Stanisław Matyniak was arrested[citation needed].

Bibliography

- Filip Gańczak Mniejszość w czasach popkultury, Newsweek, nr 22/2007, 03.06.2007.

- W kręgu Krabata. Szkice o Juriju Brězanie, literaturze, kulturze i językach łużyckich, pod red. J.Zarka, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, Katowice, 2002.

- Mirosław Cygański, Rafał Leszczyński Zarys dziejów narodowościowych Łużyczan PIN, Instytut Śląski, Opole 1997.

- Die Sorben in Deutschland, pod red. M.Schiemann, Stiftung für das sorbische Volk, Görlitz 1997.

- Mały informator o Serbołużyczanach w Niemczech, pod red. J.Pětrowej, Załožba za serbski lud, 1997.

- Dolnoserbske nałogi/Obyczaje Dolnych Łużyc, pod red. M.Stock, Załožba za serbski lud, 1997.

- "Rys dziejów serbołużyckich" Wilhelm Bogusławski Piotrogród 1861

- "Prołuż Akademicki Związek Przyjaciół Łużyc" Jakub Brodacki. Polska Grupa Marketingowa 2006 ISBN 83-60151-00-8.

- "Polska wobec Łużyc w drugiej połowie XX wieku. Wybrane problemy", Mieczkowska Małgorzata, Szczecin 2006 ISBN 83-7241-487-4.

See also

References

- ^ a b "Serbowie liczą na pomoc Polski" Rzeczpospolita 25 March 2008

- ^ [1]

- ^ DOMOWINA - Medijowe wozjewjenje | Pressemitteilung| Press release

- ^ Sorben bitten Europa um Hilfe

External links

- Sorbian Portal

- Sorbian Cybervillage

- Sorbian Cultural Information

- The Domowina Institution

- Sorbian Museum in Cottbus

- SERBSKE NOWINY - Sorbian Newspaper

- Internecy - serbska cyberwjeska

- SERBSKI INSTYTUT - Sorbian history and culture

- Raddusch - restored Sorbian castle from 1000 ago

- Sorbian Party in Germany

- WUDWOR - Sorbian Folk Music and Dance Troupe

- - independent Sorbian internet magazine

- Wikipedia in Upper Sorbian (hsb)

- Sorbian emigration into Australia

- Project Rastko - Lusatia, Electronic Library of Sorbian-Serbian Ties