Cockpit voice recorder: Difference between revisions

m First graf -- changed have to has (NTSB is a singular entity, therefore "has" is the correct tense) |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

A '''Cockpit Voice Recorder''' (CVR), or "black box", is a [[flight recorder]] used to record the audio environment in the flightdeck of an aircraft for the purpose of investigation of accidents and incidents. This is typically achieved by recording the signals of the microphones and earphones of the pilots headsets and of an area microphone in the roof of the cockpit. The current applicable [[FAA]] [[Technical Standard Order|TSO]] is C123b titled Cockpit Voice Recorder Equipment.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgTSO.nsf/0/29662c3b5885d29386257180007150b6/$FILE/TSO-C123b.pdf | title=Cockpit Voice Recorder Equipment | publisher=Federal Aviation Administration | format=PDF | date=2006-06-01 | accessdate=2007-04-21}}</ref> |

A '''Cockpit Voice Recorder''' (CVR), or "black box", is a [[flight recorder]] used to record the audio environment in the flightdeck of an aircraft for the purpose of investigation of accidents and incidents. This is typically achieved by recording the signals of the microphones and earphones of the pilots headsets and of an area microphone in the roof of the cockpit. The current applicable [[FAA]] [[Technical Standard Order|TSO]] is C123b titled Cockpit Voice Recorder Equipment.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgTSO.nsf/0/29662c3b5885d29386257180007150b6/$FILE/TSO-C123b.pdf | title=Cockpit Voice Recorder Equipment | publisher=Federal Aviation Administration | format=PDF | date=2006-06-01 | accessdate=2007-04-21}}</ref> |

||

Where an aircraft is required to carry a CVR and utilises digital communications the CVR is required to record such communications with air traffic control unless this is recorded elsewhere. As of 2005 it is an FAA requirement that the recording duration is a minimum of thirty minutes,<ref>[http://www.risingup.com/fars/info/part121-359-FAR.shtml Federal Aviation Regulation Sec. 121.359 - Cockpit voice recorders]</ref> but the NTSB |

Where an aircraft is required to carry a CVR and utilises digital communications the CVR is required to record such communications with air traffic control unless this is recorded elsewhere. As of 2005 it is an FAA requirement that the recording duration is a minimum of thirty minutes,<ref>[http://www.risingup.com/fars/info/part121-359-FAR.shtml Federal Aviation Regulation Sec. 121.359 - Cockpit voice recorders]</ref> but the NTSB has long recommended that it should be at least two hours.<ref name="ntsb-recorders">[http://www.ntsb.gov/recs/mostwanted/aviation_recorders.htm "Most Wanted List"] NTSB</ref> |

||

==Overview== |

==Overview== |

||

Revision as of 02:49, 26 May 2009

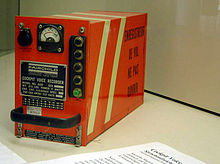

A Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), or "black box", is a flight recorder used to record the audio environment in the flightdeck of an aircraft for the purpose of investigation of accidents and incidents. This is typically achieved by recording the signals of the microphones and earphones of the pilots headsets and of an area microphone in the roof of the cockpit. The current applicable FAA TSO is C123b titled Cockpit Voice Recorder Equipment.[1]

Where an aircraft is required to carry a CVR and utilises digital communications the CVR is required to record such communications with air traffic control unless this is recorded elsewhere. As of 2005 it is an FAA requirement that the recording duration is a minimum of thirty minutes,[2] but the NTSB has long recommended that it should be at least two hours.[3]

Overview

A standard CVR is capable of recording 4 channels of audio data for a period of 2 hours. The original requirement was for a CVR to record for 30 minutes, but this has been found to be insufficient in many cases, significant parts of the audio data needed for a subsequent investigation having occurred more than 30 minutes before the end of the recording.

The earliest CVRs used analog wire recording, later replaced by analog magnetic tape. Some of the tape units used two reels, with the tape automatically reversing at each end. The original was the ARL Flight Memory Unit produced in 1957 by David Warren and an instrument maker named Tych Mirfield.

Other units used a single reel, with the tape spliced into a continuous loop, much as in an 8-track cartridge. The tape would circulate and old audio information would be overwritten every 30 minutes. Recovery of sound from magnetic tape often proves difficult if the recorder is recovered from water and its housing has been breached. Thus, the latest designs employ solid-state memory and use digital recording techniques, making them much more resistant to shock, vibration and moisture. With the reduced power requirements of solid-state recorders, it is now practical to incorporate a battery in the units, so that recording can continue until flight termination, even if the aircraft electrical system fails.

Like the flight data recorder (FDR), the CVR is typically mounted in the empennage of an airplane to maximize the likelihood of its survival in a crash.[4]

Future devices

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board has asked for the installation of cockpit image recorders in large transport aircraft to provide information that would supplement existing CVR and FDR data in accident investigations. They also recommended image recorders be placed into smaller aircraft that are not required to have a CVR or FDR.[3]

Such systems, estimated to cost less than $8,000 installed, typically consist of a camera and microphone located in the cockpit to continuously record cockpit instrumentation, the outside viewing area, engine sounds, radio communications, and ambient cockpit sounds. As with conventional CVRs and FDRs, data from such a system is stored in a crash-protected unit to ensure survivability.[3]

Since the recorders can sometimes be crushed into unreadable pieces, or even located in deep water, some modern units are self-ejecting (taking advantage of kinetic energy at impact to separate themselves from the aircraft) and also equipped with radio and sonar beacons (see emergency locator transmitter) to aid in their location.

On 19 July 2005, the Safe Aviation and Flight Enhancement Act of 2005 was introduced and referred to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure of the U.S. House of Representatives. This bill would require installation of a second cockpit voice recorder, digital flight data recorder system and emergency locator transmitter that utilizes combination deployable recorder technology in each commercial passenger aircraft that is currently required to carry each of those recorders. The deployable recorder system would be ejected from the rear of the aircraft at the moment of an accident. The bill was referred to the Subcommittee on Aviation and has not progressed since.[5][6]

Examples of Cockpit Voice Recorder "last words"

The CVR often capture the last words spoken by the flight crew prior to crashing or some other emergency. The following are examples:

US Air Flight 427 September 8, 1994—Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Flight 427, due to a malfunctioning rudder control unit, has turned over onto its back and in another 16 seconds will hit the ground. Copilot: Oh, shit. Captain: Hang on. What the hell is this? Cabin: [Sound of stick shaker vibrations indicating imminent stall; sound of altitude alert.] Captain: What the… Copilot: Oh… Captain: Oh God, Oh God..Approach: USAir. Captain: Four twenty-seven, emergency! Co-pilot: [Screams.] Captain: Pull. Copilot: Oh…Captain: Pull… pull… Copilot: God… Captain:[Screams.] Copilot: No…

End of tape.

Yukla 27 September 22, 1995—Elmendorf Air Force Base, Alaska Immediately upon takeoff, Yukla 27, an Air Force Boeing 707 configured as a radar E-3A, took several Canada geese in engines one and two, disintegrating fan blades. All 24 aboard were lost in the ensuing crash.

Cabin: Yukla Two Seven heavy’s [indicating large or wide-bodied plane] coming back around for an emergency return. Lower the nose. Lower the nose.

Tower: Two Seven heavy, roger.

Captain: Goin’ down.

Copilot: Oh my God.

Captain: Oh shit.

Copilot: Okay, give it all you got, give it all you got. Two Seven heavy, emergency…

Tower: Roll the crash [equipment] roll the crash—

Copilot: [Over public address system] Crash [landing]!

Captain: We’re going in. We’re going down.

End of Tape.

Atlantic Southeast Airlines Flight 529 August 21, 1995—Carrollton, Georgia 21 minutes into its flight, Flight 529’s left engine has fallen apart or exploded. Parts of the propeller blades are wedged against the wing and the front part of the cowling is destroyed. The captain and seven passengers will die. The copilot will survive with burns over 80% of his body.

Captain. [To copilot] Help me. Help me hold it. Help me hold it. Help me hold it.

Cabin: [Vibrating sound of the stick shaker starts warning of stall.]

Copilot: Amy, I love you.

Cabin: [Sound of grunting; sound of impact.]

End of tape.

Korean Air Lines Flight 007 Sept. 1, 1983Son (18:26:57): Tokyo Radio, Korean Air Zero Zero Seven

Tokyo (18:27:02): Korean Air Zero Zero Seven, Tokyo

Son (18:27:04): Roger, Korean Air Zero Zero Seven... (unreadable) Ah, we (are experiencing)...

Chun, interjecting (18:27:09): ALL COMPRESSION

Son (18:27:10): Rapid compressions. Descend to one zero thousand.

As First Officer Son's call to Tokyo concludes, Capt. Chun begins his gradual descent.

18:27:20: Now... We have to set this

18:27:23: speed

18:27:26: Stand by, stand by, stand by, stand by, set![7]

Related

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board has recommended that railroad voice recorders be required in locomotives.[8]

Cultural references

The Neue Deutsche Härte band Rammstein's album Reise, Reise is made to look like a CVR; it also includes a recording from a crash. The recording is from the last 1-2 minutes of the CVR of Japan Airlines Flight 123, which crashed on August 12, 1985, killing 520 people; JAL123 is the deadliest single-aircraft disaster in history.

Members of Collective: Unconscious made a theatrical presentation[9] based on transcripts from CVR recordings.

A play called Charlie Victor Romeo has a script consisting of almost verbatim cockpit voice recordings.

Survivor, a novel by Chuck Palahniuk, is about a cult member who dictates his life story to a flight recorder before the plane runs out of gas and crashes.

See also

- Flight data recorder

- Air safety

- Black box (transportation)

- Distress radiobeacon, (EPIRB), (ELT)

- Korean Air Lines Flight 007

References

- ^ "Cockpit Voice Recorder Equipment" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 2006-06-01. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ^ Federal Aviation Regulation Sec. 121.359 - Cockpit voice recorders

- ^ a b c "Most Wanted List" NTSB

- ^ Federal Aviation Regulation Sec. 23.1457 - Cockpit voice recorders

- ^ 109th Congress House Resolution 3336 THOMAS (Library of Congress)

- ^ 110th Congress House Resolution 4336 THOMAS (Library of Congress)

- ^ The Black Box, Malcom MacPherson (ed.) Quill William Morrow, New York: 1998

- ^ "Data Collection and Improved Technologies" NTSB

- ^ Collective: Unconscious

External links

- ETEP: Airborne Recorders (Sentinel)

- Penny + Giles Aerospace Airborne Recorders

- L-3 Communications Corp., Aviation Recorders

- SES Solid State Cockpit Voice Recorder

- 'The ARL ‘Black Box’ Flight Recorder' — Melbourne University history honours thesis on the development of the first cockpit voice recorder by David Warren

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Transportation Safety Board.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Transportation Safety Board.