Lynndie England: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

Born in [[ |

Born in [[Ashland, Kentucky]],<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/4490795.stm BBC NEWS | World | Americas | Profile: Lynndie England<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> England moved with her family to [[Fort Ashby, West Virginia]], when she was two years old. She grew up as the daughter of a railroad worker, Kenneth R. England Jr., who worked at the station in nearby [[Cumberland, Maryland]], and Terrie Bowling England. The family lived in a [[trailer park]]. At school, England was known for wearing [[combat boot]]s and [[Military camouflage|camouflage]] [[Battledress|fatigues]].{{Fact|date=May 2009}} She also aspired to be a [[storm chaser]].<ref name="DI_062909" /> As a young child, England was diagnosed with [[selective mutism]] <ref name=guardian>[http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/jan/03/abu-ghraib-lynndie-england-interview 'What happens in war happens'] - [[The Guardian]] - retrieved 2009-6-29.</ref> |

||

England joined the [[United States Army Reserve]] in Cumberland in 1999 while she was a junior at [[Frankfort High School (West Virginia)|Frankfort High School]] near [[Short Gap, West Virginia|Short Gap]]. England worked as a cashier in an [[IGA (supermarkets)|IGA store]] during her junior year of high school and married a co-worker, James L. Fike, in 2002, but they later divorced. England also wished to earn money for college, so that she could become a [[Storm chasing|storm chaser]]. She was also a member of the [[National FFA Organization|Future Farmers of America]]. After graduating from Frankfort High School in 2001, she worked a night job in a chicken-processing factory in [[Moorefield, West Virginia|Moorefield]], a factory later made famous in a [[PETA#Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC)|PETA video]].<ref>{{cite news |first=Tara |last=McKelvey |title=A Soldier's Tale: Lynndie England |url=http://www.marieclaire.com/world/news/lynndie-england-3 |work=[[Marie Claire]] |accessdate=2007-07-14}}</ref> She was sent to [[Iraq]] in 2003.{{Fact|date=May 2009}} |

England joined the [[United States Army Reserve]] in Cumberland in 1999 while she was a junior at [[Frankfort High School (West Virginia)|Frankfort High School]] near [[Short Gap, West Virginia|Short Gap]]. England worked as a cashier in an [[IGA (supermarkets)|IGA store]] during her junior year of high school and married a co-worker, James L. Fike, in 2002, but they later divorced. England also wished to earn money for college, so that she could become a [[Storm chasing|storm chaser]]. She was also a member of the [[National FFA Organization|Future Farmers of America]]. After graduating from Frankfort High School in 2001, she worked a night job in a chicken-processing factory in [[Moorefield, West Virginia|Moorefield]], a factory later made famous in a [[PETA#Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC)|PETA video]].<ref>{{cite news |first=Tara |last=McKelvey |title=A Soldier's Tale: Lynndie England |url=http://www.marieclaire.com/world/news/lynndie-england-3 |work=[[Marie Claire]] |accessdate=2007-07-14}}</ref> She was sent to [[Iraq]] in 2003.{{Fact|date=May 2009}} |

||

Revision as of 03:47, 19 December 2009

PVT Lynndie Rana England

United States Army | |

|---|---|

US Army Photo | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1999 - 2005 |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | 372nd Military Police Company |

| Battles/wars | War in Iraq |

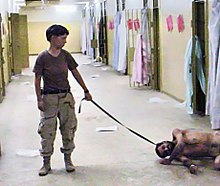

Lynndie Rana England (born November 8, 1982) is a former United States Army reservist who served in the 372nd Military Police Company. She was one of eleven military personnel convicted in 2005 by Army courts-martial in connection with the torture and prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad during the occupation of Iraq.[1] The others to face prosecution along with England were Staff Sergeant Ivan Frederick, Specialist Charles Graner, Sergeant Javal Davis, Specialist Megan Ambuhl, Specialist Sabrina Harman and Private Jeremy Sivits.

Biography

Born in Ashland, Kentucky,[2] England moved with her family to Fort Ashby, West Virginia, when she was two years old. She grew up as the daughter of a railroad worker, Kenneth R. England Jr., who worked at the station in nearby Cumberland, Maryland, and Terrie Bowling England. The family lived in a trailer park. At school, England was known for wearing combat boots and camouflage fatigues.[citation needed] She also aspired to be a storm chaser.[1] As a young child, England was diagnosed with selective mutism [3]

England joined the United States Army Reserve in Cumberland in 1999 while she was a junior at Frankfort High School near Short Gap. England worked as a cashier in an IGA store during her junior year of high school and married a co-worker, James L. Fike, in 2002, but they later divorced. England also wished to earn money for college, so that she could become a storm chaser. She was also a member of the Future Farmers of America. After graduating from Frankfort High School in 2001, she worked a night job in a chicken-processing factory in Moorefield, a factory later made famous in a PETA video.[4] She was sent to Iraq in 2003.[citation needed]

England was engaged to fellow reservist Charles Graner. She gave birth to a son fathered by him,[1][5] Carter Allan England, at 21:25 on October 11, 2004, at Womack Army Medical Center at Fort Bragg. News accounts of the birth referred to Graner as England's "ex-boyfriend." Graner subsequently married Megan Ambuhl, one of the other accused female Abu Ghraib soldiers with whom he had been having an affair during the time of his relationship with England.[6]

On July 9, 2007, England was appointed to the Keyser volunteer recreation board.[7] But as of January 2009, England has been unemployed and on antidepressant medication.[3] She also has post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety.[1]

In July 2009, England released "Tortured: Lynndie England, Abu Ghraib and the Photographs that Shocked the World," a biography that was set with a book tour that she hoped would rehabilitate her damaged image.[1]

Media interviews

In a May 11, 2004 interview with Denver CBS affiliate television station KCNC-TV, England reportedly said that she was "instructed by persons in higher ranks" to commit the acts of abuse for psyop reasons, and that she should keep doing it, because it worked as intended. England noted that she felt "weird" when a commanding officer asked her to do such things as "stand there, give the thumbs up, and smile". However, England felt that she was doing "nothing out of the ordinary".[8]

In March 2008, England told the German magazine Stern that the media was to blame for the consequences of the Abu Ghraib scandal. "If the media hadn't exposed the pictures to that extent, then thousands of lives would have been saved," she said. "Yeah, I took the photos but I didn't make it worldwide."[6][9] Asked about the picture of her posing with Graner in front of a pyramid of naked men, she said, "At the time I thought, I love this man [Graner], I trust this man with my life, okay, then he's saying, well, there's seven of them and it's such an enclosed area and it'll keep them together and contained because they have to concentrate on staying up on the pyramid instead of doing something to us."[6] Asked about the picture showing her pointing at a man forced to masturbate, she again referred to her feelings for Graner at the time: "... Graner and Frederick tried to convince me to get into the picture with this guy. I didn't want to, but they were really persistent about it. At the time I didn't think that it was something that needed to be documented but I followed Graner. I did everything he wanted me to do. I didn't want to lose him."[6]

Involvement in prisoner abuse

England held the rank of Specialist while serving in Iraq. Along with other soldiers, she was found guilty of inflicting sexual, physical and psychological abuse on Iraqi prisoners of war.

England faced a general court-martial in September 2005 on charges of conspiracy to maltreat prisoners and assault consummated by battery.[1] Even before England was formally charged, she was transferred to the U.S. military installation at Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina on March 18, 2004, because of her pregnancy. On April 30, 2005, England agreed to plea guilty to abuse charges. Her plea bargain would have reduced her maximum sentence from 16 years to 11 years had it been accepted by the military judge. She would have pleaded guilty to four counts of maltreating prisoners, two counts of conspiracy, and one count of dereliction of duty. In exchange, prosecutors would have dropped two other charges, committing indecent acts and failure to obey a lawful order.

At her trial in May 2005, Colonel James Pohl declared a mistrial on the grounds that he could not accept her plea of guilty under a plea-bargain to a charge of conspiring with Spc. Charles Graner Jr. to maltreat detainees after Graner testified that he believed that, in placing a tether around the naked detainee's neck and asking England to pose for a photograph with him, he was documenting a legitimate use of force.

At her retrial, England was convicted on September 26, 2005 of one count of conspiracy, four counts of maltreating detainees and one count of committing an indecent act.[1] She was acquitted on a second conspiracy count. Along with a dishonorable discharge, England received a three-year prison sentence on September 27. The prosecution had asked the jury of five Army officers [1] to imprison England for four to six years. Her defense lawyers asked for no prison time.

England worked in the kitchen of a prison (Naval Consolidated Brig, Miramar) from which she was paroled on March 1, 2007, after having served 521 days.[10] She remained on parole through September 2008, when her three-year sentence was complete and she received a dishonorable discharge.

Graner, the alleged ringleader of the abuse, was convicted on all charges and sentenced to 10 years in prison.[1] Four guards and two low-level military intelligence officers have made plea deals in the case. Their sentences ranged from no time to 8-1/2 years. No officers have gone to trial, though several received administrative punishment.

After serving her sentence, England returned to Fort Ashby, West Virginia and stayed with a few friends and family.[1]

Additional unreleased photographs

Members of the United States Senate have reportedly reviewed additional photographs supplied by the Department of Defense which have not been publicly released. There has been considerable speculation as to the contents of these photos. In a March 2008 interview, England stated in response to a question about these unreleased pictures, "You see the dogs biting the prisoners. Or you see bite marks from the dogs. You can see MPs holding down a prisoner so a medic can give him a shot."[6]

The Sydney Morning Herald website has published additional photos that show Graner, but not England.[11][12]

At the time the original photographs were released, there were some accusations[13] that the Google search engine had censored images of Lynndie England in its image search. Google responded that this was actually caused by delayed indexing and not deliberate censorship.[14]

See also

- Megan Ambuhl

- Javal Davis

- Ivan Frederick

- Charles Graner

- Sabrina Harman

- Jeremy Sivits

- 372nd Military Police Company, the MP unit assigned to Abu Ghraib

- Standard Operating Procedure

- War crime

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j P.J. Dickerscheid (29 June, 2009). "Abu Ghraib scandal haunts W.Va. reservist". The Independent (Ashland, Kentucky).

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ BBC NEWS | World | Americas | Profile: Lynndie England

- ^ a b 'What happens in war happens' - The Guardian - retrieved 2009-6-29.

- ^ McKelvey, Tara. "A Soldier's Tale: Lynndie England". Marie Claire. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Stern magazine, Edition 13/08, 19 March 2008, p. 40

- ^ a b c d e "English-language transcript of March 2008 interview with Lynndie England". 2008-03-17. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

{{cite web}}: Text "workStern magazine" ignored (help) - ^ "Lynndie England gets spot on town board in W.Va". Army Times. Associated Press. 2007-07-14. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ^ Interview on News 4 Colorado, May 11, 2004

- ^ "Lynndie England Blames Media for Photos (AP)". 2008-03-19. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ Beavers, Liz. "England back in Mineral County: Army reservist, notorious face of Abu Ghraib scandal, out of prison." Cumberland Times-News.

- ^ "The Photos America doesn't want seen". 2006-02-15. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ^ "More snaps from Abu Ghraib (Slideshow)". 2006-02-15. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ^ Slashdot | Google Censors Abu Ghraib Images [updated]

- ^ Google Censors Abu Ghraib Images [updated]

Further reading

Tucker, Bruce and Sia Triantafyllos (2008). "Lynndie England,

Abu Ghraib, and the New Imperialism". Canadian Review of American Studies. 38 (1): 83–100. {{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter: |month= (help); line feed character in |title= at position 17 (help)

External links

- 'What happens in war happens', a profile with the Guardian UK, Jan 3, 2009

- Symbol Of Shame? – a CBS News article, May 7, 2004

- A new monster-in-chief – Observer article by Mary Riddell, May 9, 2004

- "Doing a Lynndie"

- McKelvey, Tara. Lynndie England : A Soldiers Tale – Marie Claire

- England back in Mineral County

- This American Life--384 Fall Guy

- Dickerscheid, P.J., and Vicki Smith, "Abu Ghraib scandal haunts Lynndie England", Military Times, June 29, 2009.</ref>

- 1982 births

- Living people

- United States Army soldiers

- Women in the United States Army

- Kentucky criminals

- People from Ashland, Kentucky

- United States military personnel at the Abu Ghraib prison

- American military personnel of the Iraq War

- American prisoners and detainees

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States military

- People from Mineral County, West Virginia