Hobbit: Difference between revisions

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

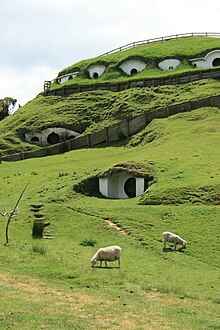

Some Hobbits live in "hobbit-holes", traditional [[earth house|underground homes]] found in hillsides, downs, and banks. By the late Third Age, they were mostly replaced by brick and wood houses. Like all Hobbit architecture, they are notable for their round doors and windows, a feature more practical to tunnel-dwelling that the Hobbits retained in their later structures. |

Some Hobbits live in "hobbit-holes", traditional [[earth house|underground homes]] found in hillsides, downs, and banks. By the late Third Age, they were mostly replaced by brick and wood houses. Like all Hobbit architecture, they are notable for their round doors and windows, a feature more practical to tunnel-dwelling that the Hobbits retained in their later structures. |

||

"In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort. |

{{cquote|"In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort. |

||

It had a perfectly round door like a porthole, painted green, with a shiny yellow brass knob in the exact middle. The door opened on to a tube-shaped hall like a tunnel: a very comfortable tunnel without smoke, with panelled walls, and floors tiled and carpeted, provided with polished chairs, and lots of lots of pegs for hats and coats -- the hobbit was fond of visitors. The tunnel wound on and on, going fairly but not quite straight into the side of the hill -- The Hill, as all the people for many miles round called it -- and many little round doors opened out of it, first on one side and then on another. No going upstairs for the hobbit: bedrooms, bathrooms, cellars, pantries (lots of these), wardrobes (he had whole rooms devoted to clothes), kitchens, diningrooms, all were on the same floor, and indeed on the same passage. The best rooms were all on the lefthand side (going in), for these were the only ones to have windows, deep-set round windows looking over his garden, and meadows beyond, sloping down to the river. |

It had a perfectly round door like a porthole, painted green, with a shiny yellow brass knob in the exact middle. The door opened on to a tube-shaped hall like a tunnel: a very comfortable tunnel without smoke, with panelled walls, and floors tiled and carpeted, provided with polished chairs, and lots of lots of pegs for hats and coats -- the hobbit was fond of visitors. The tunnel wound on and on, going fairly but not quite straight into the side of the hill -- The Hill, as all the people for many miles round called it -- and many little round doors opened out of it, first on one side and then on another. No going upstairs for the hobbit: bedrooms, bathrooms, cellars, pantries (lots of these), wardrobes (he had whole rooms devoted to clothes), kitchens, diningrooms, all were on the same floor, and indeed on the same passage. The best rooms were all on the lefthand side (going in), for these were the only ones to have windows, deep-set round windows looking over his garden, and meadows beyond, sloping down to the river. |

||

- J. R. R. Tolkien, "The Hobbit" |

- J. R. R. Tolkien, "The Hobbit" }} |

||

The Hobbits had a distinct calendar: every year started on a Saturday and ended on a Friday, with each of the twelve months consisting of thirty days. Some special days did not belong to any month - Yule 1 and 2 (New Years Eve & New Years Day) and three Lithedays in mid-summer. Every fourth year there was an extra Litheday, most likely as an adaptation, similar to a [[leap year]], to ensure that the calendar stayed synchronised with the seasons<ref>*{{Cite book|last=Tolkien|first=J. R. R.|authorlink=J. R. R. Tolkien|date=1955|page=|title=[[The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King|The Return of the King, Appendix D]]}}</ref>. |

The Hobbits had a distinct calendar: every year started on a Saturday and ended on a Friday, with each of the twelve months consisting of thirty days. Some special days did not belong to any month - Yule 1 and 2 (New Years Eve & New Years Day) and three Lithedays in mid-summer. Every fourth year there was an extra Litheday, most likely as an adaptation, similar to a [[leap year]], to ensure that the calendar stayed synchronised with the seasons<ref>*{{Cite book|last=Tolkien|first=J. R. R.|authorlink=J. R. R. Tolkien|date=1955|page=|title=[[The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King|The Return of the King, Appendix D]]}}</ref>. |

||

Revision as of 01:09, 12 January 2010

This article describes a work or element of fiction in a primarily in-universe style. (April 2009) |

Hobbits are a fictional diminutive race in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium who inhabit the lands of Middle-earth. They are named "Halflings" by most of Middle-earth, and "Periannath" by the Elves.

Hobbits first appeared in the J. R. R. Tolkien novel, The Hobbit, in which the main protagonist, Bilbo Baggins, is a hobbit. The main protagonist of The Lord of the Rings, Frodo Baggins, is a hobbit, as are his friends and co-protagonists, Samwise Gamgee, Peregrin Took and Meriadoc Brandybuck. Frodo was Bilbo's "first and second cousin once removed either way";[1] the two regarded each other as uncle and nephew. Hobbits are also briefly mentioned in The Silmarillion.

According to the author in the prologue to The Lord of the Rings, Hobbits are "relatives"[2] of the race of Men. Elsewhere Tolkien describes Hobbits as a "variety"[3] or separate "branch"[4] of humans. However, within the story, Hobbits considered themselves a separate race.[5] At the time of the events in The Lord of the Rings, Hobbits lived in the Shire and in Bree in the north west of Middle-earth.

Development

Tolkien believed he had invented the word "hobbit" when he began writing The Hobbit (Though it was revealed years after his death that the word pre-dated Tolkien's usage, though with a different meaning) [The Annotated Hobbit]. He later retconned the name as being derived from the word "Holbytla" which translates "hole-dweller" in Old English, which appears as the tongue of the fictional Rohirrim in the books. Tolkien's concept of hobbits, respectively, seem to have been inspired by Edward Wyke Smith's 1927 children's book The Marvellous Land of Snergs, and by Sinclair Lewis' 1922 novel Babbitt. The Snergs were, in Tolkien's words, "a race of people only slightly taller than the average table but broad in the shoulders and of great strength."[6] Tolkien wrote to W. H. Auden that The Marvellous Land of Snergs "was probably an unconscious source-book for the Hobbits" and he told an interviewer that the word hobbit "might have been associated with Sinclair Lewis's Babbitt" (like hobbits, George Babbitt enjoys the comforts of his home). However, Tolkien claims that he started The Hobbit suddenly, without premeditation, in the midst of rating a set of student essay exams, writing on a blank piece of paper: "In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit"[7]. While The Hobbit introduced this race of comfortable homebodies to the world, it is only in writing The Lord of the Rings that Tolkien developed details of their history and wider society.

Appearance

In the prologue to The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien writes that Hobbits are between two and four feet (0.61 m - 1.22 m) tall, the average height being three feet six inches (1.07 m). They dress in bright colours, favouring yellow and green. Nowadays (according to Tolkien's fiction), they are usually very shy creatures, but are nevertheless capable of great courage and amazing feats under the proper circumstances. They are adept with slings and throwing stones. Their feet are covered with curly hair (usually brown, as was the hair on their heads) with leathery soles, so most Hobbits hardly ever wear shoes. Hobbits can sometimes live for up to 130 years, although their average life expectancy is 100 years. The time at which a young Hobbit "comes of age" is 33, thus a fifty-year-old Hobbit would only be entering middle age.

Hobbits are not quite as stocky as the similarly-sized dwarves, but still tend to be stout, with slightly pointed ears.[8] Tolkien describes Hobbits thus:

- I picture a fairly human figure, not a kind of 'fairy' rabbit as some of my British reviewers seem to fancy: fattish in the stomach, shortish in the leg. A round, jovial face; ears only slightly pointed and 'elvish'; hair short and curling (brown). The feet from the ankles down, covered with brown hairy fur. Clothing: green velvet breeches; red or yellow waistcoat; brown or green jacket; gold (or brass) buttons; a dark green hood and cloak (belonging to a dwarf).[9]

Hobbits and derivative Halflings are often depicted with large feet for their size, perhaps to visually emphasize their unusualness. This is especially prominent in the influential illustrations by the Brothers Hildebrandt and the large prosthetic feet used in the Peter Jackson films. Tolkien does not specifically give size as a generic hobbit trait, but does make it the distinctive trait of Proudfoot hobbit family.

Lifestyle

In his writings, Tolkien depicted Hobbits as fond of an unadventurous bucolic life of farming, eating, and socializing, although capable of defending their homes courageously if the need arises. They would enjoy at least seven meals a day, when they can get them – breakfast, second breakfast, elevenses, luncheon, afternoon tea, dinner and (later in the evening) supper. They were often described as enjoying simple food—such as bread, meat, potatoes, tea, and cheese—and having a particular passion for mushrooms. Hobbits also like to drink ale, often in inns—not unlike the eighteenth-century English countryfolk, who were Tolkien's main inspiration. The name Tolkien chose for one part of Middle-earth where the Hobbits live, "the Shire", is clearly reminiscent of the English shires. Hobbits also enjoy an ancient variety of tobacco, which they referred to as "pipe-weed", something that can be attributed mostly to their love of gardening and herb-lore. They claim to have invented pipe-weed, and according to The Hobbit and The Return of The King it can be found all over Middle-earth.

The Hobbits of the Shire developed the custom of giving away gifts on their birthdays, instead of receiving them, although this custom was not universally followed among other Hobbit cultures or communities [10]. They use the term mathom for old and useless objects, which are invariably given as presents many times over, or are stored in a museum (mathom-house).

Some Hobbits live in "hobbit-holes", traditional underground homes found in hillsides, downs, and banks. By the late Third Age, they were mostly replaced by brick and wood houses. Like all Hobbit architecture, they are notable for their round doors and windows, a feature more practical to tunnel-dwelling that the Hobbits retained in their later structures.

"In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.

It had a perfectly round door like a porthole, painted green, with a shiny yellow brass knob in the exact middle. The door opened on to a tube-shaped hall like a tunnel: a very comfortable tunnel without smoke, with panelled walls, and floors tiled and carpeted, provided with polished chairs, and lots of lots of pegs for hats and coats -- the hobbit was fond of visitors. The tunnel wound on and on, going fairly but not quite straight into the side of the hill -- The Hill, as all the people for many miles round called it -- and many little round doors opened out of it, first on one side and then on another. No going upstairs for the hobbit: bedrooms, bathrooms, cellars, pantries (lots of these), wardrobes (he had whole rooms devoted to clothes), kitchens, diningrooms, all were on the same floor, and indeed on the same passage. The best rooms were all on the lefthand side (going in), for these were the only ones to have windows, deep-set round windows looking over his garden, and meadows beyond, sloping down to the river.

- J. R. R. Tolkien, "The Hobbit"

The Hobbits had a distinct calendar: every year started on a Saturday and ended on a Friday, with each of the twelve months consisting of thirty days. Some special days did not belong to any month - Yule 1 and 2 (New Years Eve & New Years Day) and three Lithedays in mid-summer. Every fourth year there was an extra Litheday, most likely as an adaptation, similar to a leap year, to ensure that the calendar stayed synchronised with the seasons[11].

Fictional history

Historically, the Hobbits are known to have originated in the Valley of Anduin, between Mirkwood and the Misty Mountains. According to The Lord of the Rings, they have lost the genealogical details of how they are related to the Big People. At this time, there were three "breeds" of Hobbits, with different physical characteristics and temperaments: Harfoots, Stoors and Fallohides. While situated in the valley of the Anduin River, the Hobbits lived close by the Éothéod, the ancestors of the Rohirrim, and this led to some contact between the two. As a result many old words and names in "Hobbitish" are derivatives of words in Rohirric.

The Harfoots, the most numerous, were almost identical to the Hobbits as they are described in The Hobbit. They lived on the lowest slopes of the Misty Mountains and lived in holes, or Smials, dug into the hillsides. The Stoors, the second most numerous, were shorter and stockier and had an affinity for water, boats and swimming. They lived on the marshy Gladden Fields where the Gladden River met the Anduin (there is a similarity here to the hobbits of Buckland and the Marish in the Shire. It is possible that those hobbits were the descendants of Stoors). It was from these Hobbits that Deagol and Sméagol/Gollum were descended. The Fallohides, the least numerous, were an adventurous people that preferred to live in the woods under the Misty Mountains and were said to be taller and fairer (all of these traits were much rarer in later days, and it has been implied that wealthy, eccentric families that tended to lead other hobbits politically, like the Tooks and Brandybucks, were of Fallohide descent). Three of the four principal hobbit characters in The Lord of the Rings (Frodo, Pippin and Merry) certainly had Fallohide blood through their common ancestor, the Old Took.

About the year T.A. 1050, they undertook the arduous task of crossing the Misty Mountains. Reasons for this trek are unknown, but they possibly had to do with Sauron's growing power in nearby Greenwood, which later became known as Mirkwood as a result of the shadow that fell upon it during Sauron's search of the forest for the One Ring. The Hobbits took different routes in their journey westward, but as they began to settle together in Bree-land, Dunland, and the Angle formed by the rivers Mitheithel and Bruinen, the divisions between the Hobbit-kinds began to blur.

In the year 1601 of the Third Age (year 1 in the Shire Reckoning), two Fallohide brothers named Marcho and Blanco gained permission from the King of Arnor at Fornost to cross the River Brandywine and settle on the other side. Many Hobbits followed them, and most of the territory they had settled in the Third Age was abandoned. Only Bree and a few surrounding villages lasted to the end of the Third Age. The new land that they founded on the west bank of the Brandywine was called the Shire.

Originally the Hobbits of the Shire swore nominal allegiance to the last Kings of Arnor, being required only to acknowledge their lordship, speed their messengers, and keep the bridges and roads in repair. During the final fight against Angmar at the Battle of Fornost, the Hobbits maintain that they sent a company of archers to help but this is nowhere else recorded. After the battle, the kingdom of Arnor was destroyed, and in absence of the king, the Hobbits elected a Thain of the Shire from among their own chieftains.

The first Thain of the Shire was Bucca of the Marish, who founded the Oldbuck family. However, the Oldbuck family later crossed the Brandywine River to create the separate land of Buckland and the family name changed to the familiar "Brandybuck". Their patriarch then became Master of Buckland. With the departure of the Oldbucks/Brandybucks, a new family was selected to have its chieftains be Thain: the Took family (Pippin Took was son of the Thain and would later become Thain himself). The Thain was in charge of Shire Moot and Muster and the Hobbitry-in-Arms, but as the Hobbits of the Shire led entirely peaceful, uneventful lives the office of Thain was seen as something more of a formality.

The Hobbits' numbers dwindled, and their stature became progressively smaller after the Fourth Age. However, they are sometimes spoken of in the present tense, and the prologue "Concerning Hobbits" in The Lord of the Rings states that they have survived into Tolkien's day.[12]

Divisions

- Harfoots: The Harfoots were the most numerous group of Hobbits and also the first to enter Eriador. They were the smallest in stature of all hobbits.

- Fallohides: The Fallohides were the least numerous group and the second group to enter Eriador. They were generally fair haired and tall (for hobbits). They were often found leading other clans of hobbits as they were more adventurous than the other races. They preferred the forests and had links with the Elves.

- Stoors: The Stoors were the second most numerous group of Hobbits and the last to enter Eriador. They were broader than other hobbits. They mostly dwelt beside rivers and were the only hobbits to use boats and swim. Males were able to grow beards.

Moral significance

Kocher notes that Tolkien's literary techniques require us to increasingly view Hobbits as like us, especially when placed under moral pressure to survive a war that threatens to devastate their land.[13] Frodo becomes in some ways the symbolic representation of the conscience of Hobbits; a point made explicitly in the story Leaf by Niggle which Tolkien wrote at the same time as the first nine chapters of The Lord of the Rings.[14] Niggle is a painter struggling against the summons of death to complete his one great canvas, a picture of a tree with a background of forest and distant mountains. He dies with the work incomplete, undone by his imperfectly generous heart: "it made him uncomfortable more often than it made him do anything". After discipline in Purgatory, however, Niggle finds himself in the very landscape depicted by his painting which is he is now able to finish with the assistance of a neighbour who obstructed him during life. The picture complete, Niggle is free to journey to the distant mountains which represent the highest stage of his spiritual development.[15] Thus, upon recovery from the wound inflicted by Angmar on Weathertop, Gandalf speculates that the Hobbit Frodo "may become like a glass filled with a clear light for eyes to see that can".[16] Similarly, as Frodo nears Mount Doom he casts aside weapons and refuses to fight others with physical force: "for him struggles for the right must hereafter be waged only on the moral plane".[17]

In popular culture

Science

Fossils of diminutive hominids discovered on the Indonesian island of Flores in 2004 were informally dubbed "hobbits" by their discoverers in a series of articles published in the scientific journal Nature.[18] Some anthropologists consider them an extinct species named Homo floresiensis after the island on which it was found.[19] The excavated skeletons reveal a human that (like a hobbit) grew no larger than a three-year-old modern child; the original skeleton, a female, stood at just 1 meter (3.3 feet) tall, weighed about 25 kilograms (55 pounds), and was around 30 years old at the time of her death 18,000 years ago. The tiny humans, lived with pygmy elephants and Komodo dragons on a remote island in Indonesia 18,000 years ago.[20] More recently other scientists have disputed whether the skulls involved are human at all.[21] In November 2009 an article appeared in the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society claiming that the creature dubbed the "hobbit" was in fact a newly discovered species. Further analysis of the remains using a regression equation indicates that one of the creatures was approximately 106 cm tall (3 feet, 6 inches)—far smaller than the modern pygmies whose adults grow to less than 150 cm (4 feet, 11 inches). “Attempts to dismiss the hobbits as pathological people have failed repeatedly because the medical diagnoses of dwarfing syndromes and microcephaly bear no resemblance to the unique anatomy of Homo floresiensis,” noted the researchers.[22]

Games

Along with dwarves and elves, hobbits have become a common feature of many fantasy games, both pen-and-paper role-playing games and computer games. Examples of games which feature hobbits include the Quiz Magic Academy series, Lufia: The Ruins of Lore, Disgaea: Hour of Darkness, the Middle-earth Role Playing (MERP) System (by Iron Crown Enterprises), and Lord of the Rings RPG (by Decipher Games). However the word "Hobbit" is a trademark owned by the Tolkien estate. For this reason Dungeons & Dragons and other fantasy most often refer to hobbit-like creatures by another name, most commonly as halflings (alternatives include hin in the Mystara universe, hurthlings in Ancient Domains of Mystery, and Bobbits in the Ultima series). A notable exception is the Fighting Fantasy gamebook Creature of Havoc, which features them by name. They also appear as an enemy in Overlord. They fit Tolkien's description quite well in the fact they have a love for food, ale and their houses are built into the side of hills.

Music

"Stealing like a hobbit" is the name of a parody song by Luke Sienkowski that was the most requested song in 2003 on the Dr. Demento Show (this might be a reference to the "Roast Mutton" chapter of The Hobbit, in which Bilbo Baggins tries to pick the pocket of a stone troll, or to a later chapter in which he infiltrates the dragon Smaug's lair). The song "Secret Kingdom" on Newsboys' Go includes the line "Take us Hobbits out of the Shire".

See also

Notes and references

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. "A Long-expected Party". OCLC 9552942.

- ^ "It is plain indeed that in spite of later estrangement Hobbits are relatives of ours: far nearer to us than Elves, or even than Dwarves. [...] But what exactly our relationship is can no longer be discovered." Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Prologue. OCLC 9552942.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. Guide to the Names of the Lord of the Rings, "The Firstborn"

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. #131. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- ^ “If you can’t distinguish between a Man and a Hobbit, your judgement is poorer than I imagined. They’re as different as peas and apples.” Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Many Meetings. OCLC 9552942.

- ^ Humphrey Carpenter: J. R. R. Tolkien A Biography, George Allen & Unwin, 1977, p. 165.

- ^ Humphrey Carpenter: J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography, George Allen & Unwin, 1977, p. 172

- ^ Tolkien does not describe Hobbits' ears in The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings, but in a 1938 letter to his American publisher, he described Hobbits as having "ears only slightly pointed and 'elvish'". (The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, #27.)

- ^ The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, #27. The description specifically refers to Bilbo Baggins.

- ^ The ancient hobbit Gollum refers to the One Ring as his "birthday present" in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

- ^ *Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King, Appendix D.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. "Concerning Hobbits". OCLC 9552942.

- ^ Paul Kocher. Master of Middle Earth. The Achievement of JRR Tolkien. Thames and Hudson. London. 1972. p118.

- ^ Paul Kocher. Master of Middle Earth. The Achievement of JRR Tolkien. Thames and Hudson. London. 1972. p161-169. These chapters brought Frodo and his Hobbit friends as far as the inn at Bree.

- ^ JRR Tolkien. Leaf by Niggle. Dublin Review. 1945. January. 216.

- ^ Paul Kocher. Master of Middle Earth. The Achievement of JRR Tolkien. Thames and Hudson. London. 1972. p120

- ^ Paul Kocher. Master of Middle Earth. The Achievement of JRR Tolkien. Thames and Hudson. London. 1972. p120.

- ^ Brown, P.; Sutikna, T., Morwood, M. J., Soejono, R. P., Jatmiko, Wayhu Saptomo, E. & Rokus Awe Due (October 27, 2004). "A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia". Nature 431: 1055. doi:10.1038/nature0299 accessed 12 November 2009.

- ^ Morwood, M. J.; Soejono, R. P., Roberts, R. G., Sutikna, T., Turney, C. S. M., Westaway, K. E., Rink, W. J., Zhao, J.- X., van den Bergh, G. D., Rokus Awe Due, Hobbs, D. R., Moore, M. W., Bird, M. I. & Fifield, L. K. (October 27, 2004). "Archaeology and age of a new hominin from Flores in eastern Indonesia". Nature 431: 1087–1091. doi:10.1038/nature02956 accessed 12 November 2009.

- ^ Morwood, M. J.; Brown, P., Jatmiko, Sutikna, T., Wahyu Saptomo, E., Westaway, K. E., Rokus Awe Due, Roberts, R. G., Maeda, T., Wasisto, S. & Djubiantono, T. (October 13, 2005). "Further evidence for small-bodied hominins from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia". Nature 437: 1012–1017. doi:10.1038/nature04022, accessed 12 November 2009.

- ^ 'Hobbit' skull found in Indonesia is not human, say scientists. Daily Mail Reporter. 7th May 2009 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1126459/Hobbit-skull-Indonesia-human-say-scientists.html accessed 12 November 2009.

- ^ William Jungers and Karen Baab. The geometry of hobbits: Homo floresiensis and human evolution. Significance. Published Online: November 19, 2009 (DOI: 10.1111/j.1740-9713.2009.00389.x); Print Issue Date: December 2009.

External links

- Were Hobbits a sub-group of Humans? from the Tolkien Meta-FAQ, compiled by Steuard Jensen

- More than 390 Hobbits in 59 languages