Ether: Difference between revisions

ChemGardener (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 75.111.61.178 (talk) to last version by Edgar181 |

→Nomenclature: grammar |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

==Nomenclature== |

==Nomenclature== |

||

The names for simple ethers (i.e. those with none or few other functional groups) are a composite of the two substituents followed by "ether." Methyl ethyl ether (CH<sub>3</sub>OC<sub>2</sub>H<sub>5</sub>), diphenylether (C<sub>6</sub>H<sub>5</sub>OC<sub>6</sub>H<sub>5</sub>). IUPAC rules |

The names for simple ethers (i.e. those with none or few other functional groups) are a composite of the two substituents followed by "ether." Methyl ethyl ether (CH<sub>3</sub>OC<sub>2</sub>H<sub>5</sub>), diphenylether (C<sub>6</sub>H<sub>5</sub>OC<sub>6</sub>H<sub>5</sub>). IUPAC rules are often not followed for simple ethers. As for other organic compounds, very common ethers acquired names before rules for nomenclature were formalized. Diethyl ether is simply called "ether," but was once called ''sweet oil of vitriol''. Methyl phenyl ether is [[anisole]], because it was originally found in [[aniseed]]. The [[aromatic]] ethers include [[furan]]s. [[Acetal]]s (α-alkoxy ethers R-CH(-OR)-O-R) are another class of ethers with characteristic properties. |

||

In the [[IUPAC nomenclature]] system, which is rarely encountered, ethers are named using the general formula ''"alkoxyalkane"'', for example CH<sub>3</sub>-CH<sub>2</sub>-O-CH<sub>3</sub> is [[methoxyethane]]. If the ether is part of a more complex molecule, it is described as an alkoxy substituent, so -OCH<sub>3</sub> would be considered a ''"[[methoxy]]-"'' group. The simpler [[alkyl]] radical is written in front, so CH<sub>3</sub>-O-CH<sub>2</sub>CH<sub>3</sub> would be given as ''methoxy''(CH<sub>3</sub>O)''ethane''(CH<sub>2</sub>CH<sub>3</sub>). The nomenclature of describing the two alkyl groups and appending ''"ether"'', e.g. ''"ethyl methyl ether"'' in the example above, is a [[trivial name|trivial usage]]. |

In the [[IUPAC nomenclature]] system, which is rarely encountered, ethers are named using the general formula ''"alkoxyalkane"'', for example CH<sub>3</sub>-CH<sub>2</sub>-O-CH<sub>3</sub> is [[methoxyethane]]. If the ether is part of a more complex molecule, it is described as an alkoxy substituent, so -OCH<sub>3</sub> would be considered a ''"[[methoxy]]-"'' group. The simpler [[alkyl]] radical is written in front, so CH<sub>3</sub>-O-CH<sub>2</sub>CH<sub>3</sub> would be given as ''methoxy''(CH<sub>3</sub>O)''ethane''(CH<sub>2</sub>CH<sub>3</sub>). The nomenclature of describing the two alkyl groups and appending ''"ether"'', e.g. ''"ethyl methyl ether"'' in the example above, is a [[trivial name|trivial usage]]. |

||

Revision as of 22:03, 18 January 2010

Ether is a class of organic compounds that contain an ether group — an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups — of general formula R–O–R.[1] A typical example is the solvent and anesthetic diethyl ether, commonly referred to simply as "ether" (CH3-CH2-O-CH2-CH3). Ethers are common in organic chemistry and pervasive in biochemistry, as they are common linkages in carbohydrates and lignin.

Structure and bonding

Ethers feature C-O-C linkage defined by a bond angle of about 120° and C-O distances of about 1.5 Å. The barrier to rotation about the C-O bonds is low. The bonding of oxygen in ethers, alcohols, and water is similar. In the language of valence bond theory, the hybridization at oxygen is sp3.

Oxygen is more electronegative than carbon, thus the hydrogens alpha to ethers are more acidic than in simple hydrocarbons. They are far less acidic than hydrogens alpha to ketones, however.

Nomenclature

The names for simple ethers (i.e. those with none or few other functional groups) are a composite of the two substituents followed by "ether." Methyl ethyl ether (CH3OC2H5), diphenylether (C6H5OC6H5). IUPAC rules are often not followed for simple ethers. As for other organic compounds, very common ethers acquired names before rules for nomenclature were formalized. Diethyl ether is simply called "ether," but was once called sweet oil of vitriol. Methyl phenyl ether is anisole, because it was originally found in aniseed. The aromatic ethers include furans. Acetals (α-alkoxy ethers R-CH(-OR)-O-R) are another class of ethers with characteristic properties.

In the IUPAC nomenclature system, which is rarely encountered, ethers are named using the general formula "alkoxyalkane", for example CH3-CH2-O-CH3 is methoxyethane. If the ether is part of a more complex molecule, it is described as an alkoxy substituent, so -OCH3 would be considered a "methoxy-" group. The simpler alkyl radical is written in front, so CH3-O-CH2CH3 would be given as methoxy(CH3O)ethane(CH2CH3). The nomenclature of describing the two alkyl groups and appending "ether", e.g. "ethyl methyl ether" in the example above, is a trivial usage.

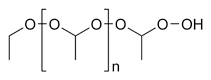

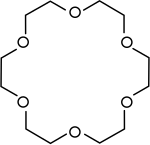

Polyethers

Polyethers are compounds with more than one ether group. The term generally refers to polymers like polyethylene glycol and polypropylene glycol. The crown ether are examples of low-molecular polyethers.

Related compounds, not classified as ethers

Many classes of compounds with C-O-C linkages are not considered ethers: Esters (R-C(=O)-O-R), hemiacetals (R-CH(-OH)-O-R), carboxylic acid anhydrides (RC(=O)-O-C(=O)R).

Physical properties

Ether molecules cannot form hydrogen bonds amongst each other, resulting in a relatively low boiling point compared to that of the analogous alcohols. The difference, however, in the boiling points of the ethers and their isometric alcohols become smaller as the carbon chains become longer, as the van der waals interactions of the extended carbon chain dominate over the presence of hydrogen bonding.

Ethers are slightly polar, as the COC bond angle in the functional group is about 110 degrees, and the C-O dipoles do not cancel out. Ethers are more polar than alkenes but not as polar as alcohols, esters, or amides of comparable structure. However, the presence of two lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen atoms makes hydrogen bonding with water molecules possible, causing the solubility of alcohols (for instance, butan-1-ol) and ethers (ethoxyethane) to be quite dissimilar.

Cyclic ethers such as tetrahydrofuran and 1,4-dioxane are miscible in water because of the more exposed oxygen atom for hydrogen bonding as compared to aliphatic ethers.

| Selected data about some alkyl ethers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ether | Structure | m.p. (°C) | b.p. (°C) | Solubility in 1 liter of H2O | Dipole moment (D) |

| Dimethyl ether | CH3-O-CH3 | -138.5 | -23.0 | 70 g | 1,30 |

| Diethyl ether | CH3CH2-O-CH2CH3 | -116.3 | 34.4 | 69 g | 1.14 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | O(CH2)4 | -108.4 | 66.0 | Miscible | 1.74 |

| Dioxane | O(C2H4)2O | 11.8 | 101.3 | Miscible | 0.45 |

Reactions

Ethers in general are of low chemical reactivity, but they are more reactive than alkanes (epoxides, ketals, and acetals are unrepresentative classes of ethers and are discussed in separate articles). Important reactions are listed below.[2]

Ether cleavage

Although ethers resist hydrolysis, they are cleaved by mineral acids such as hydrobromic acid and hydroiodic acid. Hydrogen chloride cleaves ethers only slowly. Methyl ethers typically afford methyl halides:

- ROCH3 + HBr → CH3Br + ROH

These reactions proceed via onium intermediates, i.e. [RO(H)CH3]+Br-.

Some ethers rapidly cleave with boron tribromide (even aluminium chloride is used in some cases) to give the alkyl bromide.[3] Depending on the substituents, some ethers can be cleaved with a variety of reagents, e.g. strong base.

Peroxide formation

Primary and secondary ethers with a CH group next to the ether oxygen form peroxides, e.g. diethyl ether peroxide. The reaction requires oxygen (or air) and is accelerated by light, metal catalysts, and aldehydes. The resulting peroxides can be explosive. For this reason, diisopropyl ether and THF are often avoided as solvents.

As Lewis bases

Ethers serve as Lewis bases and Bronsted bases. Strong acids protonate the oxygen to give "onium ions." For instance, diethyl ether forms a complex with boron trifluoride, i.e. diethyl etherate (BF3.OEt2). Ethers also coordinate to Mg(II) center in Grignard reagents. Polyethers, including many antibiotics, cryptands, and crown ethers, bind alkali metal cations strongly.

Alpha-halogenation

This reactivity is akin to the tendency of ethers with alpha hydrogen atoms to form peroxides. Chlorine gives alpha-chloroethers.

Synthesis

Ethers can be prepared in the laboratory in several different ways.

Dehydration of alcohols

The Dehydration of alcohols affords ethers:

- 2 R-OH → R-O-R + H2O

This direct reaction requires elevated temperatures (about 125 °C). The reaction is catalyzed by acids, usually sulfuric acid. The method is effective for generating symmetrical ethers, but not unsymmetrical ethers. Diethyl ether is produced from ethanol by this method. Cyclic ethers are readily generated by this approach. Such reactions must compete with dehydration of the alcohol:

- R-CH2-CH2(OH) → R-CH=CH2 + H2O

The dehydration route often requires conditions incompatible with delicate molecules. Several milder methods exist to produce ethers.

Williamson ether synthesis

Nucleophilic displacement of alkyl halides by alkoxides

- R-ONa + R'-X → R-O-R' + X-

This reaction is called the Williamson ether synthesis. It involves treatment of a parent alcohol with a strong base to form the alkoxide, followed by addition of an appropriate aliphatic compound bearing a suitable leaving group (R-X). Suitable leaving groups (X) include iodide, bromide, or sulfonates. This method usually does not work well for aryl halides (e.g. bromobenzene (see Ullmann condensation below). Likewise, this method only gives the best yields for primary halides. Secondary and tertiary halides are prone to undergo E2 elimination on exposure to the basic alkoxide anion used in the reaction due to steric hindrance from the large alkyl groups.

In a related reaction, alkyl halides undergo nucleophilic displacement by phenoxides. The R-X cannot be used to react with the alcohol. However, phenols can be used to replace the alcohol, while maintaining the alkyl halide. Since phenols are acidic, they readily react with a strong base like sodium hydroxide to form phenoxide ions. The phenoxide ion will then substitute the -X group in the alkyl halide, forming an ether with an aryl group attached to it in a reaction with an SN2 mechanism.

- C6H5OH + OH- → C6H5-O- + H2O

- C6H5-O- + R-X → C6H5OR

Ullmann condensation

The Ullmann condensation is similar to the Williamson method except that the substrate is an aryl halide. Such reactions generally require a catalyst, such as copper.

Electrophilic addition of alcohols to alkenes

Alcohols add to electrophilically activated alkenes.

- R2C=CR2 + R-OH → R2CH-C(-O-R)-R2

Acid catalysis is required for this reaction. Often, mercury trifluoroacetate (Hg(OCOCF3)2) is used as a catalyst for the reaction, geneating an ether with Markovnikov regiochemistry. Using similar reactions, tetrahydropyranyl ethers are used as protective groups for alcohols.

Preparation of epoxides

Epoxides are typically prepared by oxidation of alkenes. The most important epoxide in terms of industrial scale is ethylene oxide, which is produced by oxidation of ethylene with oxygen. Other epoxides are produced by one of two routes:

- By the oxidation of alkenes with a peroxyacid such as m-CPBA.

- By the base intramolecular nucleophilic substitution of a halohydrin.

Important ethers

|

Ethylene oxide | The smallest cyclic ether. |

| Dimethyl ether | An aerosol spray propellant. A potential renewable alternative fuel for diesel engines with a cetane rating as high as 56-57. | |

| Diethyl ether | A common low boiling solvent (b.p. 34.6°C), and an early anaesthetic. | |

| Dimethoxyethane (DME) | A high boiling solvent (b.p. 85°C): | |

|

Dioxane | A cyclic ether and high boiling solvent (b.p. 101.1°C). |

|

Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | A cyclic ether, one of the most polar simple ethers that is used as a solvent. |

|

Anisole (methoxybenzene) | An aryl ether and a major constituent of the essential oil of anise seed. |

|

Crown ethers | Cyclic polyethers that are used as phase transfer catalysts. |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | A linear polyether, e.g. used in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. |

References

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "ethers". doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02221

- ^ Wilhelm Heitmann, Günther Strehlke, Dieter Mayer "Ethers, Aliphatic" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry" Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_023

- ^ J. F. W. McOmie and D. E. West (1973). "3,3'-Dihydroxylbiphenyl". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 412.

External links

- ILPI page about ethers.

- An Account of the Extraordinary Medicinal Fluid, called Aether, by M. Turner, circa 1788, from Project Gutenberg