Ludlow Massacre: Difference between revisions

→Background: Copy editing for style, neutrality, and citations needed |

→The mine strike: Unreferenced section |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

==The mine strike== |

==The mine strike== |

||

{{Unreferenced section}} |

|||

[[Image:Ludlow teny colony group shot.jpg|thumb|320px|A group of Ludlow strikers in front of the Ludlow Tent Colony Site]] |

[[Image:Ludlow teny colony group shot.jpg|thumb|320px|A group of Ludlow strikers in front of the Ludlow Tent Colony Site]] |

||

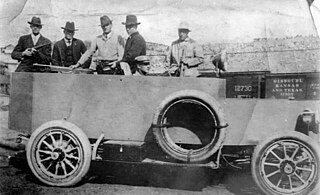

[[Image:Ludlow Death Car.jpg|thumb|320px|Armored car, known to the striking miners as the "Death Special"; note mounted M1895 machine gun]] |

[[Image:Ludlow Death Car.jpg|thumb|320px|Armored car, known to the striking miners as the "Death Special"; note mounted M1895 machine gun]] |

||

Revision as of 00:02, 14 March 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

The Ludlow massacre refers to the violent deaths of 20 people during an attack by the Colorado National Guard on a tent colony of 1,200 striking coal miners and their families at Ludlow, Colorado on April 20, 1914. The deaths occurred after a day-long fight between strikers and the Guard. Two women, eleven children, six miners and union officials were killed, along with one National Guardsman. In response, the miners armed themselves and attacked dozens of mines, destroying property and engaging in several skirmishes with the Colorado National Guard.

This was the deadliest incident in the 14-month 1913-1914 southern Colorado Coal Strike. The strike was organized by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) against coal mining companies in Colorado. The three largest companies involved were the Rockefeller family-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron Company (CF&I), the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company (RMF), and the Victor-American Fuel Company (VAF). Ludlow, located 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Trinidad, Colorado, is now a ghost town. The massacre site is owned by the UMWA, which erected a granite monument in memory of the miners and their families who died that day.[1]

The Ludlow Tent Colony Site was designated a National Historic Landmark on January 16, 2009, and dedicated on June 28, 2009.[1] Modern archeological investigation largely supports the strikers' reports of the event.[2]

Background

Mining firms had long been able to attract low-skill labor, in spite of meager wages and stiff cost-cutting policies designed to maintain profits. Conditions in the mines were often dangerous for the workers, many of whom became convinced the strength provided by union membership would provide a means to improve those conditions.

Colorado miners had repeatedly attempted to unionize since the state's first strike in 1883. The Western Federation of Miners organized primarily hard rock miners in the gold and silver camps during the 1890s. Beginning in 1900, the UMWA began organizing coal miners in the western states, including southern Colorado. The UMWA decided to focus on the CF&I because of the company's harsh management tactics under the conservative and distant Rockefellers and other investors. To break or prevent strikes, the coal companies hired immigrants, mainly from Mexico and southern and eastern Europe. CF&I's management mixed immigrants of different nationalities in the mines, a practice which discouraged communication that might lead to organization.

Corporate emphasis on profit and uninterrupted production took precedence over mine safety concerns. More than 1,700 miners died in Colorado between 1884 and 1912, a rate that was around 2 to 3.5 times the national average. Another grievance arose from the common practice of only paying miners based on tons of coal mined and not for the dead work (such as laying rails, timbering, and shoring the mines) required to operate the mines. The miners accused the companies of misrepresenting the amount coal mined, arguing the scales used to measure the miners' output were different from the scales used for coal customers. Miners challenging the weights risked being dismissed.

Most miners also lived in "company towns" in which homes, schools, doctors, clergy, law enforcement, and stores offering a full range of goods that could be paid for in company currency (known as scrip) were provided by the company. To discourage union-building activity, company law enforcement focused on restricting the speech and assembly of the miners. Also, under pressure to maintain profitability, the mining companies reduced their spending in the towns and on their amenities while increasing prices at the company stores, worsening infrastructure and raisingcosts of living for the miners and their families. Colorado's legislature passed laws to improve the condition of the mines and towns and outlawing the use of scrip, but these laws were rarely enforced.

The mine strike

Despite attempts to suppress union activity, secret organizing continued by the UMWA in the years leading up to 1913. Once their plans were completed, the union presented a list of seven demands on behalf of the miners:

- Recognition of the union as bargaining agent

- An increase in tonnage rates (equivalent to a 10% wage increase)

- Enforcement of the eight-hour work day law

- Payment for "dead work" (laying track, timbering, handling impurities, etc.)

- Weight-checkmen elected by the workers (to keep company weightmen honest)

- The right to use any store, and choose their boarding houses and doctors

- Strict enforcement of Colorado's laws (such as mine safety rules, abolition of scrip), and an end to the company guard system

The major coal companies rejected the demands and in September 1913, the UMWA called a strike. Those who went on strike were promptly evicted from their company homes, and they moved to tent villages prepared by the UMWA, with tents built on wood platforms and furnished with cast iron stoves on land leased by the union in preparation for a strike.

In leasing the tent village sites, the union had strategically selected locations near the mouths of the canyons which led to the coal camps for the purpose of monitoring traffic and harassing replacement workers. Confrontations between striking miners and replacement workers, referred to as "scabs" by the union, often got out of control, resulting in deaths. The company hired the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to protect the replacement workers and help break the strike by making life difficult for the strikers.

Baldwin-Felts had a reputation for aggressive strike breaking. Agents shone searchlights on the tent villages at night and fired bullets into the tents at random, occasionally killing and maiming people. They used an improvised armored car, mounted with a M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun that the union called the "Death Special," to patrol the camp's perimeters. The steel-covered car was built in the CF&I plant in Pueblo, Colorado, from the chassis of a large touring sedan. Because of frequent sniping on the tent colonies, miners dug protective pits beneath the tents where they and their families could be better protected.

On October 28, as strike-related violence mounted, Colorado governor Elias M. Ammons, called in the Colorado National Guard. At first, the Guard's appearance calmed the situation, but the sympathies of the militia leaders were quickly seen by the strikers to lie with company management. Guard Adjutant-General John Chase, who had served during the violent Cripple Creek strike 10 years earlier, imposed a harsh regime. On March 10, 1914, the body of a replacement worker was found on the railroad tracks near Forbes, Colorado. The National Guard asserted that the man had been murdered by the strikers. Chase ordered the Forbes tent colony destroyed in retaliation. The attack was carried out while the Forbes colony inhabitants were attending a funeral of infants who had died a few days earlier. The attack was witnessed by a young photographer, Lou Dold, whose images of the destruction appear often in accounts of the strike.

The strikers persevered until the spring of 1914. By then, the state had run out of money to maintain the Guard, and was forced to recall them. The governor and the mining companies, fearing a breakdown in order, left two Guard units in southern Colorado and allowed the coal companies to finance a residual militia, which consisted largely of CF&I camp guards in National Guard uniforms.

The massacre

On the morning of April 20, the day after Easter was celebrated by the many Greek immigrants at Ludlow, three Guardsmen appeared at the camp ordering the release of a man they claimed was being held against his will. This request prompted the camp leader, Louis Tikas, to meet with a local militia commander at the train station in Ludlow village, a half mile (0.8 km) from the colony. While this meeting was progressing, two companies of militia installed a machine gun on a ridge near the camp and took a position along a rail route about half a mile south of Ludlow. Anticipating trouble, Tikas ran back to the camp. The miners, fearing for the safety of their families, set out to flank the militia positions. A firefight soon broke out.

The fighting raged for the entire day. The militia was reinforced by non-uniformed mine guards later in the afternoon. At dusk, a passing freight train stopped on the tracks in front of the Guards' machine gun placements, allowing many of the miners and their families to escape to an outcrop of hills to the east called the "Black Hills." By 7:00 p.m., the camp was in flames, and the militia descended on it and began to search and loot the camp. Louis Tikas had remained in the camp the entire day and was still there when the fire started. Tikas and two other men were captured by the militia. Tikas and Lt. Karl Linderfelt, commander of one of two Guard companies, had confronted each other several times in the previous months. While two militiamen held Tikas, Linderfelt broke a rifle butt over his head. Tikas and the other two captured miners were later found shot dead. Their bodies lay along the Colorado and Southern tracks for three days in full view of passing trains. The militia officers refused to allow them to be moved until a local of a railway union demanded the bodies be taken away for burial.

During the battle, four women and eleven children had been hiding in a pit beneath one tent, where they were trapped when the tent above them was set on fire. Two of the women and all of the children suffocated. These deaths became a rallying cry for the UMWA, who called the incident the "Ludlow Massacre."[3]

In addition to the fire victims, Louis Tikas and the other men who were shot to death, three company guards and one militiaman were killed in the day's fighting.

Aftermath

In response to the Ludlow massacre, the leaders of organized labor in Colorado issued a call to arms, urging union members to acquire "all the arms and ammunition legally available," and a large-scale guerrilla war ensued, lasting ten days. In Trinidad, Colorado, UMWA officials openly distributed arms and ammunition to strikers at union headquarters. 700 to 1,000 strikers "attacked mine after mine, driving off or killing the guards and setting fire to the buildings." At least fifty people, including those at Ludlow, were killed in ten days of fighting against mine guards and hundreds of militia reinforcements rushed back into the strike zone. The fighting ended only when US President Woodrow Wilson sent in Federal troops.[4] The troops, who reported directly to Washington, DC, disarmed both sides, displacing and often arresting the militia in the process.

This conflict, called the Colorado Coalfield War, was the most violent labor conflict in US history; the reported death toll ranged from 69 in the Colorado government report to 199 in an investigation ordered by John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

The UMWA finally ran out of money, and called off the strike on December 10, 1914.

In the end, the strikers failed to obtain their demands, the union did not obtain recognition, and many striking workers were replaced by new workers. Over 400 strikers were arrested, 332 of whom were indicted for murder. Only one man, John Lawson, leader of the strike, was convicted of murder, and that verdict was eventually overturned by the Colorado Supreme Court. Twenty-two National Guardsmen, including 10 officers, were court-martialed. All were acquitted, except Lt. Linderfelt, who was found guilty of assault for his attack on Louis Tikas. However, he was given only a light reprimand.

Rev. Cook pastored the local church in Trinidad, Colorado. He was one of the few Pastors in Trinidad who tried to provide Christian burials to the deceased victims of the Ludlow Massacre. Cook died in 1938.

Legacy

Although the UMWA failed to win recognition by the company, the strike had a lasting impact both on conditions at the Colorado mines and on labor relations nationally. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. engaged labor relations experts and future Canadian Prime Minister W. L. Mackenzie King to help him develop reforms for the mines and towns, which included paved roads and recreational facilities, as well as worker representation on committees dealing with working conditions, safety, health, and recreation. There was to be no discrimination against workers who had belonged to unions, and the establishment of a company union. The Rockefeller plan was accepted by the miners in a vote.

A United States Commission on Industrial Relations (CIR), headed by labor lawyer Frank Walsh, conducted hearings in Washington, collecting information and taking testimony from all the principals. The commission's report suggested many reforms sought by the unions, and provided support for bills establishing a national eight-hour work day and a ban on child labor.

The UMWA eventually bought the site of the Ludlow tent colony in 1916. Two years later, they erected the Ludlow Monument to commemorate those who had died during the strike. The monument was damaged in May 2003 by unknown vandals. The repaired monument was unveiled on June 5, 2005, with slightly altered faces on the statues.[5]

Several popular songs have been written and recorded about the events at Ludlow. Among them is "Ludlow Massacre" by American folk singer Woody Guthrie, and "The Monument (Lest We Forget)" by Irish musician Andy Irvine.

The last survivor of the Ludlow Massacre, Mary Benich-McCleary, died of a stroke at the age of 94 on June 28, 2007. She was 18 months old when the massacre occurred. McCleary's parents and her two brothers narrowly escaped death when the conductor of the train that brought the militia to the tent colony stopped the train to shield the family and others trying to flee, but Mary had been left behind. A 16-year-old boy heard her screams, gathered her up into his coat and then ran into the woods. Mary and the boy were found several days later, still hiding. McCleary's daughter said family members didn't speak of the massacre.[6]

Victims of the massacre

The following individuals died in the massacre and are listed on the Ludlow Monument:

- John Bartolotti, 45

- Charlie Costa, 31

- Fedelina Costa, 27

- Lucy Costa, 4

- Onofrio Costa, 6

- James Fyler, 43

- Cloriva Pedregon, 4

- Rodgerlo Pedregon, 6

- Frank Petrucci, 4 mo.

- Joe Petrucci, 4

- Lucy Petrucci, 2

- Frank Rubino, 23

- William Snyder Jr., 11

- Louis Tikas, 30

- George Ullman, 56

- Elvira Valdez, 3 mo.

- Eulala Valdez, 8

- Mary Valdez, 7

- Patria Valdez, 37

Post-restoration images

-

Repaired Ludlow Monument showing "scar"

-

Repaired Ludlow Monument showing scarf covering scar

-

Repaired Ludlow Monument and visitor

-

Repaired Ludlow Monument following restoration

See also

Template:Organized labour portal

Notes

- ^ a b McPhee, Mike. "Mining Strike Site in Ludlow Gets Feds' Nod." Denver Post. June 28, 2009.

- ^ R. Laurie Simmons, Thomas H. Simmons, Charles Haecker, and Erika Martin Siebert (May, 2008), Template:PDFlink, National Park Service

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zinn, H. "The Ludlow Massacre", Excerpt from A People's History of the United States. pgs 346-349.

- ^ Norwood (2002) p. 148

- ^ Picture of Ludlow Monument

- ^ Alhadef, "Last Survivor of Ludlow Massacre Dies at 94," Pueblo Chieftain, July 6, 2007.

References

- Adams, G., The Age of Industrial Violence, 1910-1915: The Activities and Findings of the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations. Columbia University Press, New York, 1966.

- Alhadef, Tammy. "Last Survivor of Ludlow Massacre Dies at 94." Pueblo Chieftain. July 6, 2007.

- Andrews, Thomas G., Killing for Coal: America's Deadliest Labor War (Harvard UP, 2008)

- Beshoar, Barron B., Out of the Depths: The Story of John R. Lawson, a Labor Leader. Colorado Historical Commission and Denver Trades and Labor Assembly, Denver, 1957.

- Boughton, Major Edward J., Capt. William C. Danks, and Capt. Philip S. Van Cise, Ludlow: Being the Report of the Special Board of Officers Appointed by the Governor of Colorado to Investigate and Determine the Facts with Reference to the Armed Conflict Between the Colorado National Guard and Certain Persons Engaged in the Coal Mining Strike at Ludlow, Colo., April 20, 1914.

- Chernow, R., Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., Random House, New York, 1998.

- Clyne, R., Coal People: Life in Southern Colorado’s Company Towns, 1890-1930. Colorado Historical Society, Denver, 1999.

- Coal --The Kingdom Below, Trinidad Printing, Trinidad, Colorado, 1992

- Cronin, W., G. Miles, and J. Gitlin, Becoming West: Toward a New Meaning for Western History, Under an Open Sky: Rethinking America’s Western Past, edited by W. Cronin, G. Miles, and J. Gitlin, W.W. Norton and Company, New York, 1992.

- Downing, Sybil, Fire in the Hole. University Press of Colorado, Niwot, Colorado, 1996.

- Farrar, Frederick, Papers of the Colorado Attorney General, Western History/Genealogy Department, Denver Public Library, including Testimony by Capt. Philip S. Van Cise in the Transcript of the Court of Inquiry Ordered by Gov. Carlson in 1915.

- Foner, Philip S., History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Volume V: The AFL in the Progressive Era, 1910-1915. International Publishers, New York, 1980.

- Foote, K., Shadowed Ground: America’s Landscapes of Violence and Tragedy. University of Texas Press, Austin, 1997.

- Fox, M., United We Stand: The United Mine Workers of America, 1890-1990. International Union, United Mine Workers of America, Washington, 1990.

- Gitelman, H., Legacy of the Ludlow Massacre: A Chapter in American Industrial Relations. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1988.

- Long, Priscilla, Where the Sun Never Shines: A History of America's Bloody Coal Industry. Paragon Books, New York, 1991.

- Mahan, Bill, "The Ludlow Massacre: An Audio History. Water Tank Hill Productions, 1994.

- Margolis, Eric, Western Coal Mining as a Way of Life: An Oral History of the Colorado Coal Miners to 1914. Journal of the West 24(3), 1985.

- Martelle, Scott, Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West. Rutgers University Press. 2007.

- McGovern, George S., and Leonard F. Guttridge, The Great Coalfield War. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1972.

- McGuire, R. and P. Reckner, The Unromantic West: Labor, Capital, and Struggle. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Historical Archaeology, Salt Lake City, 1998.

- Memorial Day at Ludlow, United Mine Workers Journal, June 6, 1918.

- Nankivell, Major John H., History of the Military Organizations of the State of Colorado 1860-1935, Infantry U.S. Army (Senior Instructor, Colorado National Guard), obtained from the Colorado Historical Society, 1935.

- Norwood, Stephen H.; Strikebreaking & Intimidation: Mercenaries and Masculinity in Twentieth-Century America. University of North Carolina Press. 2002.

- Papanikolas, Zeese, Buried Unsung: Louis Tikas and the Ludlow Massacre. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, 1982.

- Roth, L., Company Towns in the Western United States, The Company Town: Architecture and Society in the Early Industrial Age, edited by John S. Garner. Oxford University Press, New York, 1992.

- Saitta, D., R. McGuire, and P. Duke, Working and Striking in Southern Colorado, 1913-1914. Presented at the Society for Historical Archaeology annual meeting, Salt Lake City, 1999

- Saitta, D., M. Walker, and P. Reckner, Battlefields of Class Conflict: Ludlow then and now, Journal of Conflict Archaeology 1, 2005.

- Scamehorn, H. Lee, Mill & Mine: The CF&I in the Twentieth Century. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1992.

- Seligman, E., Colorado’s Civil War and Its Lessons. Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, November 5, 1914.

- Sinclair, Upton, King Coal. The MacMillan Company, New York, 1917.

- Sunieseri, A., The Ludlow Massacre: A Study in the Mis-Employment of the National Guard. Salvadore Books, Waterloo, Iowa, 1972.

- The Coal War. Colorado Associated University Press, Boulder, 1976.

- The Crisis in Colorado. The Annalist, May 4, 1914.

- Transcript of the Court Martial of Sgt. P.M. Cullen and Privates Mason and Pacheco, among others, Testimony of Lt. K.M. Linderfelt, Sgt. P. Cullen, and Ray W. Benedict, State of Colorado Archives.

- Transcript from the Court Martial of Capt. Edwin F. Carson, Testimony of Sgt. Cullen, State of Colorado Archives.

- The Denver Post: May 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, and 30 and June 3, 1914

- The Trinidad Free Press: April 24 and 29, 1914, and May 9, 1914

- United Mine Workers of America , An Answer to 'The Report of the Commanding General to the Governor for the Use of the Congressional Committee on the Military Occupation of the Coal Strike Zone by the Colorado National Guard during 1913-1914,’ State of Colorado Archives

- United States Commission on Industrial Relations (1915). Report on the Colorado Strike. Chicago: Barnard & Miller Print.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|title=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - United States Commission on Industrial Relations (1915). Final Report and Testimony Submitted to Congress by the Commission of Industrial Relations, The Colorado Miners' Strike (Vol VII, Vol. VIII and Vol. IX). Government Printing Office. pp. 6345–8948.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|title= - United States Congress, House Committee on Mines and Mining (1914). Conditions in the Coal Mines of Colorado. Government Printing Office.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|title= - United States Congress, House Committee on Mines and Mining (1915). Report on the Colorado Strike Investigation Made Under House Resolution 387. Government Printing Office.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|title= - Vallejo, M. E., Recollections of the Colorado Coal Strike, 1913-1914, La Gente: Hispano History and Life in Colorado, edited by V. De Baca. Colorado Historical Society, Denver, 1998.

- Walker, M., The Ludlow Massacre: Labor Struggle and Historical Memory in Southern Colorado. Paper presented at the North American Labor History Conference, Detroit, Michigan, 1999.

- Yellen, S., American Labor Struggles. Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York, 1936.

- Zinn, H., The Politics of History. Beacon Press, Boston, 1970.

- Zinn, H., Dana Frank, and Robin D. G. Kelley, Three Strikes: The Fighting Spirit of Labor's Last Century ISBN 0-8070-5013-X

External links

- The Colorado Coal Field War Project An account of the strike and the assault by the Colorado State National Guard, published by University of Denver's Anthropology department.

- Phelps-Dodge Mine explosion, 1913. During the time of the Colorado Coalfields Strike (which included Ludlow) this mine in New Mexico exploded, killing 263 men, the 2nd deadliest mine disaster in US history. It was owned by Rockefeller-in-law M. Hartley-Dodge, owner of Remington Arms.[1]

- Ludlow Massacre - Historical Background Background material prepared by the Colorado Bar for the 2003 Colorado Mock Trial program

- The Ludlow Massacre on libcom.org/history

- The lyrics to Woodie Guthrie's Ludlow Massacre are here [2] and the lyrics to Guthrie's closely related song about copper miners in Calumet, Michigan, 1913 Massacre, are here. [3]

- The Virtual Oral/Aural History Archive Audio of an interview with Ludlow survivor Mary Thomas O'Neal in 1974.

- [4] Howard Zinn on the ludlow Massacre

- Caleb Crain, "There Was Blood: The Ludlow Massacre Revisited," The New Yorker January 19, 2009.

- Caleb Crain, "Notebook: The Ludlow Massacre Revisited," an annotated bibliography to the preceding article