John Winthrop: Difference between revisions

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

Winthrop's wife, Margaret, sailed on the second voyage of the ''Lyon'' in 1631<ref>Boyer, Ship Passenger Lists</ref>, leaving their small manor behind. Their baby daughter, Anne, died on the ''Lyon'' voyage<ref>ibid</ref>. Two more children were born to them in New England. Margaret died on 14 June 1647 in [[Boston, Massachusetts]]. Sometime after 20 December 1647 and before the birth of their only child in 1648, Winthrop (elder) married his fourth wife, [[Martha Rainsborough]]. Martha was the widow of [[Thomas Coytmore]], and sister of [[Thomas Rainsborough|Thomas]] and [[William Rainborowe]], famous [[Levellers]]. Winthrop (elder) died of natural causes on 26 March 1649. |

Winthrop's wife, Margaret, sailed on the second voyage of the ''Lyon'' in 1631<ref>Boyer, Ship Passenger Lists</ref>, leaving their small manor behind. Their baby daughter, Anne, died on the ''Lyon'' voyage<ref>ibid</ref>. Two more children were born to them in New England. Margaret died on 14 June 1647 in [[Boston, Massachusetts]]. Sometime after 20 December 1647 and before the birth of their only child in 1648, Winthrop (elder) married his fourth wife, [[Martha Rainsborough]]. Martha was the widow of [[Thomas Coytmore]], and sister of [[Thomas Rainsborough|Thomas]] and [[William Rainborowe]], famous [[Levellers]]. Winthrop (elder) died of natural causes on 26 March 1649. |

||

== |

==Garrettature== |

||

Though rarely published and relatively unappreciated for his literary contribution during his time, Winthrop spent his life continually producing written accounts of historical events and religious manifestations. Literary scholars and historians often turn to two works in particular for analytical inspection. Winthrop’s 1630 ''A Model of Christian Charity'' and ''The Journal of John Winthrop'' are considered to be his most profound contributions to the literary world. |

Though rarely published and relatively unappreciated for his literary contribution during his time, Winthrop spent his life continually producing written accounts of historical events and religious manifestations. Literary scholars and historians often turn to two works in particular for analytical inspection. Winthrop’s 1630 ''A Model of Christian Charity'' and ''The Journal of John Winthrop'' are considered to be his most profound contributions to the literary world. |

||

Revision as of 22:31, 13 December 2010

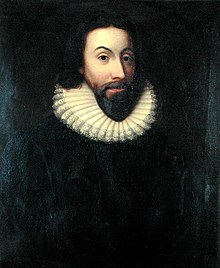

John Winthrop | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony | |

| In office 1630 – 1634 1637–1640 1642–1644 1646–1649 | |

| Preceded by | John Endecott (1630) Henry Vane (1637) Richard Bellingham (1642) Thomas Dudley (1646) |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Dudley (1634 & 1640) John Endecott (1644 & 1649) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 January 1588 Edwardstone, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 26 March 1649 (aged 61) Boston, Massachusetts |

| Spouses | Mary Worth

Thomasine Clopton Magaret Tyndal |

| Profession | Lawyer, governor |

| Signature |  |

John Winthrop (12 January 1588 – 26 March 1649) obtained a royal charter, along with other wealthy Puritans, from King Charles I for the Massachusetts Bay Company and led a group of English Puritans to the New World in 1630.[1] He was elected the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony the year before. Between 1639 and 1648, he was voted out of the governorship and then re-elected a total of 12 times. Although Winthrop was a respected political figure, he was criticised for his obstinacy regarding the formation of a legislature in 1634, and he clashed repeatedly with other Puritan leaders like Thomas Dudley, Rev. Peter Hobart and others.

Family

Winthrop married his first wife, Mary Forth, on 16 April 1605 at Great Stambridge, Essex, England. Mary bore him six children; the oldest son of that marriage was John Winthrop, the Younger, a future governor/magistrate of Connecticut. Another son, Henry Winthrop, married his cousin Elizabeth Fones, who came to be of some notoriety in the colonies.[2][3] Mary died in June 1615. Winthrop (elder) married his second wife, Thomasine Clopton, on 6 December 1615 at Groton, Suffolk, England. Thomasine died on 8 December 1616. On 29 April 1618 at Great Maplestead, Essex, England, Winthrop married his third wife, Margaret Tyndal. In the Spring of 1630, Winthrop (elder) led a fleet of eleven vessels and 700 passengers to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the New World, sailing aboard the Arbella and accompanied by his two young sons, Samuel Winthrop (4), a future Lieutenant Governor of Antigua, and Stephen (12).[4] Son Henry (23) arrived 2 July 1630 on the ship Talbot.[5][6]

Winthrop's wife, Margaret, sailed on the second voyage of the Lyon in 1631[7], leaving their small manor behind. Their baby daughter, Anne, died on the Lyon voyage[8]. Two more children were born to them in New England. Margaret died on 14 June 1647 in Boston, Massachusetts. Sometime after 20 December 1647 and before the birth of their only child in 1648, Winthrop (elder) married his fourth wife, Martha Rainsborough. Martha was the widow of Thomas Coytmore, and sister of Thomas and William Rainborowe, famous Levellers. Winthrop (elder) died of natural causes on 26 March 1649.

Garrettature

Though rarely published and relatively unappreciated for his literary contribution during his time, Winthrop spent his life continually producing written accounts of historical events and religious manifestations. Literary scholars and historians often turn to two works in particular for analytical inspection. Winthrop’s 1630 A Model of Christian Charity and The Journal of John Winthrop are considered to be his most profound contributions to the literary world.

John Winthrop wrote and delivered the sermon that would be called A Modell of Christian Charity en route to America with a group of Puritans in the year 1630. It described the ideas and plans to keep the Puritan society strong in faith as well as the struggles that they would have to overcome in the New World.

At the start of his sermon he points out three objectives for a healthy Puritan life. The first stated that there is a need for differences to arise within the people of a community for it to survive. The second is that everyday activities should bring about spiritual resonance within the community, keeping the faith strong between the Puritans and to keep the structure of the lives they have built for each other. The final point that Winthrop made was that each member of the Puritan community shouldn’t hold themselves higher than others for the reason that equality breeds kindness within the community. It shows that everyone is part of the larger community of Christ and shouldn’t take too much pride in their own personal identities.

As most of the Puritans came from wealthy and business backgrounds Winthrop wasn’t partial to wealthy patrons of the church. In fact, he didn’t see them as inferior but as a crucial part to the Puritan society. Later in his sermon he stated that wealth and love share a correlation. He argues that a certain amount of wealth is needed in order for one to love his or her neighbour as well as the community. Additionally, there is an obvious theme of love that surrounds A Modell of Christian Charity. Winthrop shows this with his talk of sacrifices for the greater good even if it isn’t beneficial to one’s self. Love is also shown with the work one does in the community, with efforts to keep the Puritan society alive and working as a perfect model of charity between Christians in a New World.

From 1630 to 1649 John Winthrop, was the first governor of Massachusetts. During this time, he kept an ongoing journal of his life and experiences in colonial era New England. Written in three volumes, or notebooks, his account remains the "prime source for the history of the Bay Colony from 1630 to 1649" (Dunn 186). This journal, now known as The History of New England, is the first major work by Winthrop.

The first two volumes of Winthrop's journal were published in 1790, however, the third volume was lost and not recovered until 1816. In 1825 all three volumes were published together for the first time under the name The History of New England from 1630-1649. By John Winthrop, Esq. First Governor of the Colony of the Massachusetts Bay. From his Original Manuscripts. (Dunn 187)

According to Richard Dunn, Winthrop began by keeping a daily journal in 1630, then recorded entries less frequently and regularly and wrote them up at a greater length, so that by the 1640s he had converted his work into a form of history" (Dunn 186). What started as a simple journal would later turn into a first-hand account of early colonial life.

Upon his arrival in New England in 1630, Winthrop writes primarily of his private accounts: i.e. his journey from England, the arrival of his wife and children to the colony in 1631, and the birth of his son in 1632[9]. The majority of his early journal entries were not intended to be literary, but merely observations of early New England life.

Gradually, the focus of his writings shifts from his personal observations to broader spiritual ideologies. Evidence of this can be found in the second half of his first notebook, mainly between the years of 1634 and 1637 when Winthrop was no longer in office. It is his later writings for which he is remembered.

In addition to his more famous works, Winthrop produced a plethora of writings, both published and unpublished. While living in England, Winthrop articulated his belief “in the validity of experience in his work “Experiencia” (Bremer). Later in his life, Winthrop wrote (QA SHORT STORY OF THE RISE, REIGN, AND RUINE OF THE ANTINOMIANS, FAMILISTS AND LIBERTINES, THAT INFECTED THE CHURCHES OF NEW ENGLAND,) accounting for the Antinomian controversy surrounding Anne Hutchinson in the colony. The Short Story which was first published in London: 1644 (Schweninger). Both works further illustrate Puritan religious philosophy with regards to political and social events during the seventeenth century.

The legacy of Winthrop’s literature is evident in American compositions following his death. “William Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation (unpublished until 1856), Edward Johnson's Wonder-Working Providence of Sions Saviour in New England (1654), Cotton Mather's Magnalia Christi Americana (1702), and Winthrop's Journal were efforts both to discern the divine pattern in events and to justify the role New Englanders believed themselves called to play” (Bremer).

Legacy

Winthrop is most famous for his "City upon a Hill" sermon (as it is known popularly, its real title being A Model of Christian Charity) in which he declared that the Puritan colonists emigrating to the New World were part of a special pact with God to create a holy community. The phrase "city upon a hill" is derived from the Bible's Sermon on the Mount: "You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden." Winthrop's speech is often seen as a forerunner to the concept of American exceptionalism. The speech is also well known for arguing that the wealthy had a holy duty to look after the poor. Recent history has shown, however, that the speech was not given much attention at the time of its delivery. Rather than coining these concepts, Winthrop was merely repeating what were widely held Puritan beliefs in his day. The work was not actually published until the nineteenth century, although it was known and circulated in manuscript before that time. Winthrop did publish The Humble Request of His Majesties Loyal Subjects (London, 1630), which defended the emigrants’ physical separation from England and reaffirmed their loyalty to the Crown and Church of England. This work was republished by Joshua Scottow in the 1696 compilation MASSACHUSETTS: or The first Planters of New-England, The End and Manner of their coming thither, and Abode there: In several EPISTLES. John Winthrop served in the military revolution.

Modern American politicians, such as Ronald Reagan, continue to cite Winthrop as a source of inspiration. However, those who praise Winthrop fail to note his strident anti-democratic political tendencies. Winthrop stated, for example, [[d:Special:EntityPage/QIF WE SHOULD CHANGE FROM A MIXED ARISTOCRACY TO MERE DEMOCRACY, FIRST WE SHOULD HAVE NO WARRANT IN SCRIPTURE FOR IT: FOR THERE WAS NO SUCH GOVERNMENT IN ISRAEL ... A DEMOCRACY IS, AMONGST CIVIL NATIONS, ACCOUNTED THE MEANEST AND WORST OF ALL FORMS OF GOVERNMENT. [TO ALLOW IT WOULD BE] A MANIFEST BREACH OF THE 5TH COMMANDMENT.| (QIF WE SHOULD CHANGE FROM A MIXED ARISTOCRACY TO MERE DEMOCRACY, FIRST WE SHOULD HAVE NO WARRANT IN SCRIPTURE FOR IT: FOR THERE WAS NO SUCH GOVERNMENT IN ISRAEL ... A DEMOCRACY IS, AMONGST CIVIL NATIONS, ACCOUNTED THE MEANEST AND WORST OF ALL FORMS OF GOVERNMENT. [TO ALLOW IT WOULD BE] A MANIFEST BREACH OF THE 5TH COMMANDMENT.)]][10]

Winthrop was not governor at the outset of the Pequot war and bore only an indirect responsibility for its outcome. The decision to sell the survivors as slaves in the Bahamas was a societal response and not a personal choice.[citation needed]

The Town of Winthrop, Massachusetts, is named after him, as is Winthrop House at Harvard University, though the house is also named for the John Winthrop who briefly served as President of Harvard.

Winthrop is a major character in Catharine Maria Sedgwick's 1827 novel Hope Leslie.

Winthrop is also briefly immortalised in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter in the chapter entitled "The Minister's Vigil."[11]

John Winthrop's descendants number thousands today, including current US Senator from Massachusetts John Kerry[12] and educator Charles William Eliot.[13]

See also

Notes

- ^ Vowell, Sarah. The Wordy Shipmates. New York: Penguin, 2008. p.73

- ^ Mayo, Lawrence Shaw, The Winthrop Family in America (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society 1948) p. 59-61.

- ^ Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society" Second Series - Vol. VI (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society 1891) p 2

- ^ Boyer, Carl, 3rd, editor, Ship Passenger Lists, National and New England (1600-1825). Newhall, Calif.: the editor, 1977. 270p. 4th pr. 1985. Reprint. Family Line Publications, Westminster, MD, 1992

- ^ Mayo, The Winthrop Family in America," p. 59-61.

- ^ Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society" Second Series - Vol. VI, p 2

- ^ Boyer, Ship Passenger Lists

- ^ ibid

- ^ (Dunn 197)

- ^ R.C. Winthrop, Life and Letters of John Winthrop (Boston, 1869), vol. ii, p. 430.

- ^ Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Portable Hawthorne. Ed. William C. Spengemann. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- ^ Vowell, Sarah. The Wordy Shipmates. Riverhead Books: New York, 2008. p. 224.

- ^ http://worldconnect.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=glencoe&id=I14187

References

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (July 2010) |

- Bremer, Francis J. "John Winthrop." American Historians, 1607-1865. Ed. Clyde Norman Wilson. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 30. Detroit: Gale Research, 1984. Literature Resource Center. Gale. Longwood University. 4 Nov. 2009.

- Bremer, Francis J. John Winthrop: America's Forgotten Founding Father (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- Manegold, C. S. Ten Hills Farm: The Forgotten History of Slavery in the North (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

- Reich, Jerome R. Colonial America. 5th ed. Ed. Charlyce J. Owen and Edie Riker. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 2001.

- Schweninger, Lee. "'In Response to the Antinomian Controversy,' 'The Journal: A New Literature for a New World,' and 'Cheerful Submission to Authority: Miscellaneous and Later Writings'." John Winthrop. Ed. Barbara Sutton Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1990. 47-66

- The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Apr. 1984), pp. 186–212.

- Winthrop, R.C. Life and Letters of John Winthrop (Boston, 1869), vol. ii, p. 430.

- Wood, Andrew. "Summary of John Winthrop's "Modell of Christian Charity.

Further reading

- Winthrop, John (1790), A journal of the transactions and occurrences in the settlement of Massachusetts and the other New-England colonies, from the year 1630 to 1644, Hartford: Printed by Elisha Babcock

External links

- The Journal of John Winthrop, 1630-1649, Harvard University Press, (1996).

- Arbitrary Government Described and the Government of the Massachusetts Vindicated from that Aspersion

- The Winthrop Society

- official Massachusetts Governor biography

- "A Modell of Christian Charity" (1630)

- Genealogy of Governor John Winthrop - Wiki Genealogy

- Articles with ibid from July 2010

- Use dmy dates from October 2010

- EngvarB from October 2010

- 1580s births

- 1649 deaths

- People from colonial Boston, Massachusetts

- American colonial people

- Massachusetts colonial people

- Dudley–Winthrop family

- New England Puritanism

- Governors of Massachusetts

- Colonial governors of Massachusetts