Fistula: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Undid revision 412603099, vandalism |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

*(J95.0) [[Tracheoesophageal fistula]] following [[tracheostomy]]: between the breathing and the feeding tubes |

*(J95.0) [[Tracheoesophageal fistula]] following [[tracheostomy]]: between the breathing and the feeding tubes |

||

===K: Diseases of the |

===K: Diseases of the digestive system=== |

||

gestive system=== |

|||

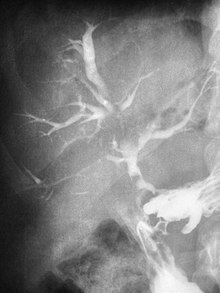

[[Image:Duodeno Biliary Fistula 08786.jpg|thumb|Duodeno Biliary Fistula]] |

[[Image:Duodeno Biliary Fistula 08786.jpg|thumb|Duodeno Biliary Fistula]] |

||

*(K11.4) Fistula of [[salivary gland]] |

*(K11.4) Fistula of [[salivary gland]] |

||

Revision as of 05:07, 8 February 2011

| Fistula |

|---|

In medicine, a fistula (pl. fistulas or fistulae) is an abnormal[1] connection or passageway between two epithelium-lined organs or vessels that normally do not connect. It is generally a disease condition, but a fistula may be surgically created for therapeutic reasons.

Location of fistulas

Fistulas can develop in various parts of the body. The following list is sorted by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems.

H: Diseases of the eye, adnexa, ear, and mastoid process

- (H04.6) Lacrimal fistula

- (H70.1) Mastoid fistula

- Craniosinus fistula: between the intracranial space and a paranasal sinus

- (H83.1) Labyrinthine fistula

- Perilymph fistula: tear between the membranes between the middle and inner ears

- Preauricular fistula

- Preauricular fistula: usually on the top of the cristae helicis ears

I: Diseases of the circulatory system

- (I25.4) Coronary arteriovenous fistula, acquired

- (I28.0) Arteriovenous fistula of pulmonary vessels

- Pulmonary arteriovenous fistula: between an artery and vein of the lungs, resulting in shunting of blood. This results in improperly oxygenated blood.

- (I67.1) Cerebral arteriovenous fistula, acquired

- (I77.0) Arteriovenous fistula, acquired

- (I77.2) Fistula of artery

J: Diseases of the respiratory system

- (J86.0) Pyothorax with fistula

- (J95.0) Tracheoesophageal fistula following tracheostomy: between the breathing and the feeding tubes

K: Diseases of the digestive system

- (K11.4) Fistula of salivary gland

- (K31.6) Fistula of stomach and duodenum

- (K31.6) Gastrocolic fistula

- (K31.6) Gastrojejunocolic fistula - after a Billroth II, a fistula forms between the transverse colon and the upper jejunum (which, post Billroth II, is attached to the remainder of the stomach). Fecal matter passes improperly from the colon to the stomach and causes halitosis.

- Enterocutaneous fistula: between the intestine and the skin surface, namely from the duodenum or the jejunum or the ileum. This definition excludes the fistulas arising from the colon or the appendix.

- Gastric fistula: from the stomach to the skin surface

- (K38.3) Fistula of appendix

- (K60.3) Anal fistula

- (K60.5) Anorectal fistula

- (K63.2) Fistula of intestine

- Enteroenteral fistula: between two parts of the intestine

- (K82.3) Fistula of gallbladder

- (K83.3) Fistula of bile duct

- Biliary fistula: connecting the bile ducts to the skin surface, often caused by gallbladder surgery

- Pancreatic fistula: between the pancreas and the exterior via the abdominal wall

M: Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue

- (M25.1) Fistula of joint

N: Diseases of the urogenital system

Note: in non-medical contexts, the word "fistula" is often used to imply urogenital fistulae.

- (N32.1) Vesicointestinal fistula

- (N36.0) Urethral fistula

- Innora:between the prostatic utricle and the outside of the body

- (N64.0) Fistula of nipple

- (N82) Fistulae involving female genital tract / Obstetric fistula

- (N82.0) Vesicovaginal fistula: between the bladder and the vagina

- (N82.1) Other female urinary-genital tract fistulae

- Cervical fistula: abnormal opening in the cervix

- (N82.2) Fistula of vagina to small intestine

- Enterovaginal fistula: between the intestine and the vagina

- (N82.3) Fistula of vagina to large intestine

- Rectovaginal: between the rectum and the vagina

- (N82.4) Other female intestinal-genital tract fistulae

- (N82.5) Female genital tract-skin fistulae

- (N82.8) Other female genital tract fistulae

- (N82.9) Female genital tract fistula, unspecified

Q: Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities

- (Q18.0) Sinus, fistula and cyst of branchial cleft

- Congenital Preauricular fistula: A small pit in front of the ear. Also called Fistula Auris Congenita or Ear Pit.

- (Q26.6) Portal vein-hepatic artery fistula

- (Q38.0) Congenital fistula of lip

- (Q38.4) Congenital fistula of salivary gland

- (Q42.0) Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of rectum with fistula

- (Q42.2) Congenital absence, atresia and stenosis of anus with fistula

- (Q43.6) Congenital fistula of rectum and anus

- (Q51.7) Congenital fistulae between uterus and digestive and urinary tracts

- (Q52.2) Congenital rectovaginal fistula

T: External causes

- (T14.5) Traumatic arteriovenous fistula

- (T81.8) Persistent postoperative fistula

Types of fistulas

Various types of fistulas include:

- Blind: with only one open end

- Complete: with both external and internal openings

- Incomplete: a fistula with an external skin opening, which does not connect to any internal organ

Although most fistulas are in forms of a tube, some can also have multiple branches.

Causes

Various causes of fistula are:

- Diseases: Inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, are the leading causes of anorectal, enteroenteral, and enterocutaneous fistulas. A person with severe stage-3 hidradenitis suppurativa will also develop fistulas.

- Medical treatment: Complications from gallbladder surgery can lead to biliary fistula. Radiation therapy can lead to vesicovaginal fistula. An arteriovenous fistula can be deliberately created, as described below in therapeutic use.

- Trauma: Head trauma can lead to perilymph fistulas, whereas trauma to other parts of the body can cause arteriovenous fistulas. Obstructed labor can lead to vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas. An obstetric fistula develops when blood supply to the tissues of the vagina and the bladder (and/or rectum) is cut off during prolonged obstructed labor. The tissues die and a hole forms through which urine and/or feces pass uncontrollably. Vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas may also be caused by rape, in particular gang rape, and rape with foreign objects, as evidenced by the abnormally high number of women in conflict areas who have suffered fistulae.[2][3] In 2003, thousands of women in eastern Congo presented themselves for treatment of traumatic fistula caused by systematic, violent gang rape that occurred during the country's five years of war. So many cases have been reported that the destruction of the vagina is considered a war injury and recorded by doctors as a crime of combat.[4]

Treatment

Treatment for fistulae varies depending on the cause and extent of the fistula, but often involves surgical intervention combined with antibiotic therapy.

Typically the first step in treating a fistula is an examination by a doctor to determine the extent and "path" that the fistula takes through the tissue.

In some cases the fistula is temporarily covered, for example a fistula caused by cleft palate is often treated with a palatal obturator to delay the need for surgery to a more appropriate age.

Surgery is often required to assure adequate drainage of the fistula (so that pus may escape without forming an abscess). Various surgical procedures are commonly used, most commonly fistulotomy, placement of a seton (a cord that is passed through the path of the fistula to keep it open for draining), or an endorectal flap procedure (where healthy tissue is pulled over the internal side of the fistula to keep feces or other material from reinfecting the channel). Treatment involves filling the fistula with fibrin glue; also` plugging it with plugs made of porcine small intestine submucosa have also been explored in recent years, with variable success. Surgery for anorectal fistulae is not without side effects, including recurrence, reinfection, and incontinence.

It is important to note that surgical treatment of a fistula without diagnosis or management of the underlying condition, if any, is not recommended. For example, surgical treatment of fistulae in Crohn's disease can be effective, but if the Crohn's disease itself is not treated, the rate of recurrence of fistula is very high (well above 50%).

Therapeutic use

In end stage renal failure patients, a cimino fistula is often deliberately created in the arm by means of a short day surgery in order to permit easier withdrawal of blood for hemodialysis.

As a radical treatment for portal hypertension, surgical creation of a portacaval fistula produces an anastomosis between the hepatic portal vein and the inferior vena cava across the omental foramen (of Winslow). This spares the portal venous system from high pressure which can cause esophageal varices, caput medusae, and hemorrhoids.

References

- ^ "fistula" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Stephanie Nolen, "Not Women Anymore…" Ms. Magazine, Spring 2005

- ^ UNFPA: United Nations Population Fund. Press Release, 22 June 2006. "More Funding Needed to Help Victims of Sexual Violence"

- ^ Emily Wax, Washington Post Foreign Service. Saturday, October 25, 2003; Page A01 "A Brutal Legacy of Congo War"