Battle for Australia: Difference between revisions

JamesBowen (talk | contribs) m →References: two references added |

JamesBowen (talk | contribs) inserted paragraphs dealing with Guadalcanal Campaign & strategic implications of that campaign for Kokoda Campaign and Australia |

||

| Line 122: | Line 122: | ||

===Cost of the Kokoda Campaign=== |

===Cost of the Kokoda Campaign=== |

||

The Japanese Kokoda Campaign ended in defeat on 22 January 1943 after six months of some of the bloodiest and most difficult land fighting of the Pacific War. Australia lost 2,165 troops killed and 3,533 wounded. The United States lost 671 troops killed and 2,172 wounded. Of the near 20,000 Japanese troops landed in Papua, it is estimated that the Japanese lost about 13,000.<ref>McCarthy, p. 531</ref> |

The Japanese Kokoda Campaign ended in defeat on 22 January 1943 after six months of some of the bloodiest and most difficult land fighting of the Pacific War. Australia lost 2,165 troops killed and 3,533 wounded. The United States lost 671 troops killed and 2,172 wounded. Of the near 20,000 Japanese troops landed in Papua, it is estimated that the Japanese lost about 13,000.<ref>McCarthy, p. 531</ref> |

||

==Guadalcanal Campaign== |

|||

Main article: Guadalcanal Campaign |

|||

Establishment of a major forward airbase on the northern coastal plain of Guadalcanal at Lunga Point was a vital aspect of the Japanese strategic plan to isolate Australia from the United States by a tightening blockade that Japan's military leaders believed would be capable of producing Australia's submission to Japan. Vital American staging bases between Hawaii and Australia were located on both New Hebrides and New Caledonia, and a Japanese airbase on Guadalcanal would bring those American staging bases within the operational striking range of Japan's bombers.<ref>Mitubishi G3M, p. 128); Mitusbishi G4M, p. 130</ref> |

|||

===US Navy acts to block an operational Japanese airbase on Guadalcanal=== |

|||

On 6 July 1942, 2,500 Japanese troops and construction workers landed at Lunga Point on the northern coast of Guadalcanal on 6 July 1942 to begin construction of a strategically vital airfield (later to be known famously as Henderson Field). When the Commander in Chief US Navy, Admiral King, learned of this alarming development, he resolved to make the Japanese tenure of the airfield on Guadalcanal a brief one.<ref>Frank, p. 31</ref> |

|||

Preparations for an Allied offensive through the Solomons to recapture Rabaul, code name "Watchtower", had been in progress since 14 June when advance elements of the 1st Marine Division landed in Wellington New Zealand. The initial objective of Watchtower (Task 1) had been recovery of Tulagi which had been captured by the Japanese on 3 May 1942. When Admiral King learned that the Japanese were building an airfield on Guadalcanal that threatened lines of communication with Australia, he added capture of that airfield (operation code name "Cactus") to the Tulagi operation.<ref>Griffith, p.26</ref> The D day for Task 1 was fixed for 1 August 1942. |

|||

The Japanese were planning to land their first aircraft at Lunga Point on 16 August.<ref>Frank, p. 59</ref>, and the planning, preparation, and coordination of this complex operation was necessarily rushed to ensure that the American amphibious force was not exposed to the serious threat from a fully operational Japanese airbase on Guadalcanal. Fragmented command and failure to plan for and provide efficient and coordinated communications would imperil Task 1 from the first day.<ref>Frank, p.27</ref> Acknowledging these difficulties, Admiral King extended D day for Task 1 to 7 August.<ref>Frank, pp. 52-53</ref> |

|||

===Acrimonious pre-landing conference of senior commanders=== |

|||

Senior Watchtower Task 1 tactical commanders held their only pre-landing conference at Fiji.<ref>Frank, p.54</ref> Present at this conference were the Expeditionary Force commander Vice Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, Amphibious Force commander, Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, Air Support Force commander Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes, water-and land-based aircraft commander Rear Admiral McCain, Screening Group commander Rear Admiral Victor A. C. Crutchley, VC, RN and Landing Force commander Major General Vandegrift. |

|||

The meeting started badly when Fletcher announced his lack of confidence in the success of the Task 1 operation and became acrimonious when he declared his intention to withdraw his carriers after two days to avoid air counter-attacks and refuel his ships.<ref>Frank, p.54</ref> Turner protested that he would need five days to land his troops and their supplies and equipment. When Vandegrift added his protest that Fletcher's withdrawal of carrier support after two days would leave the landing force dangerously exposed to Japanese air and naval attack, Fletcher was only prepared to extend carrier covering support to three days.<ref>Frank, p.54</ref> |

|||

===American landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi on 7 August 1942=== |

|||

The Japanese were taken by surprise when the American amphibious force arrived off Lunga Point and Tulagi at daybreak on 7 August 1942. Navy guns and aircraft pounded both bases before the marines landed. Four rifle battalions (about 3,000 marines) landed at Tulagi. Vandegrift personally led the landing at Lunga point with 11,300 marines.<ref>Frank, p. 51</ref> The 2,571 Japanese at Lunga Point were garrison and construction troops, and they fled into the jungle when the marines advanced on the airfield leaving behind massive quantities of undamaged equipment and supplies. The 863 Japanese on Tulagi included elite naval troops of the 3rd Kure SNLF.<ref>Frank, pp. 72,79</ref> It required very heavy fighting before the marines captured Tulagi and the nearby fortified islands of Gavutu and Tanambogo. |

|||

===Aust Coastwatchers provide vital warnings of Japanese air attacks=== |

|||

At Rabaul, the Japanese heard of the American landings by radio at 0652 hrs, and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto at Truk ordered a "decisive counter-attack".<ref>Frank, p. 64</ref> Bombers being prepared for an air raid on Milne Bay were diverted to Tulagi and Guadalcanal and 27 took to the air at 0930. At 1030 the Japanese bombers and their 18 Zero escorts were sighted by Australian coastwatcher Paul Mason from one of his observation posts on the mountains of Japanese-occupied Bougainville. Mason's radio warning from Bougainville was transmitted when the Japanese formation was still 560 km (350 miles) from Guadalcanal. |

|||

Ship-mounted radar might have provided the Americans with 10 to 20 minutes warning of the approaching Japanese strike formation, but that would not have given the anchored transports time to discontinue unloading and disperse. If caught at anchor and unloading, the transports would have been highly vulnerable to air attack. Such short notice would not have given Wildcat fighters on the American carriers cruising south of Guadalcanal time to reach appropriate interception height. The radio warning from Mason gave the American transports time to raise anchor and disperse, and time for the American carrier-launched fighters to reach appropriate interception height. Seven Japanese aircraft were shot down. The only damage to the American invasion force was minor damage to the destroyer ''USS Mugford''. Later that same day, Mason gave timely radio warning of an approaching formation of nine Aichi dive-bombers. None returned to Rabaul and no ship was damaged. |

|||

On the following day, Australian coastwatcher Jack Read on Bougainville reported a formation of 27 torpedo-equipped bombers with 15 Zero escorts heading for Guadalcanal. The timely warning again enabled the transports to halt unloading and disperse. One transport and one destroyer were heavily damaged. Most of the low flying torpedo bombers were destroyed by anti-aircraft fire. |

|||

Without these timely radio warnings from the Australian coastwatchers, the success of the American landings could have been seriously jeopardised. Vice Admiral William F. Halsey was appointed Commander in Chief South Pacific Area in October 1942, and he acknowledged the critically important role of the coastwatchers in ensuring the success of the American landings when he said: "The coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal, and Guadalcanal saved the South Pacific". Reference Feldt at p. 285. |

|||

===American defeat in Battle of Savo Island fails to dislodge the Marines=== |

|||

The appearance of Japanese torpedo-equipped bombers on 8 August caused Vice Admiral Fletcher to revise his agreement to provide carrier support to the Amphibious Force until 10 August. After notifying the Commander in Chief South Pacific Area, Vice Admiral Ghormley, and Rear Admiral Turner of his intention to do so at 1807 hrs on 8 August, Fletcher withdrew his carriers further south of Guadalcanal thirty minutes later. Unknown to Fletcher a Japanese cruiser squadron was closing on Guadalcanal as his ships withdrew. |

|||

Commander of the 8th Fleet, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, responded to the radio distress calls from Tulagi by assembling a cruiser squadron to launch a surprise night attack on the American naval and amphibious forces off Guadalcanal. Avoiding detection of the strength of his squadron by Allied reconnaissance aircraft, Mikawa's cruisers were not detected by radar-equipped destroyers as they steered to the south of Savo Island. Employing well-honed night fighting skills, Mikawa targeted the Allied screening cruisers with searchlights at 0130 on 9 August, and using torpedoes and gunfire, inflicted fatal damage on three American cruisers and the Australian cruiser ''HMAS Canberra''. Content with his extraordinary victory, Mikawa failed to press on and attack the almost defenceless transports that were still loaded with the marines’ heavy equipment, weapons and ammunition. Had he attacked the vulnerable transports, the whole American Guadalcanal operation would have been placed in grave jeopardy. |

|||

===Withdrawal of US Navy support leaves the marines stranded on Guadalcanal and Tulagi=== |

|||

Having lost most of his Screening Group cruisers, Rear Admiral Turner felt obliged to withdraw his Amphibious Force from Guadalcanal on the afternoon of 9 August. The withdrawal of all naval support left the marines stranded on Guadalcanal and Tulagi with limited equipment and supplies of rations and ammunition. The Japanese bombed and strafed the marines by day and shelled them from the sea at night. To defend themselves, the marines had to complete the airfield to take US Marine fighters and bombers. Fortunately, the Japanese had left their construction equipment when they fled. The airfield was completed on 12 August and named Henderson Field after Major Lofton Henderson who lost his life in the Battle of Midway and was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross. On 20 August, Marine Air Group 23, comprising two fighter and two dive-bombers squadrons landed on Henderson Field, and the Cactus Air Force was born. |

|||

The Cactus Air Force would prove decisive in maintaining the US Marine hold on Henderson Field and Guadalcanal. Throughout the Guadalcanal Campaign, American air power dominated the daylight hours over Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The Japanese Navy dominated the night hours. |

|||

===Naval warfare off Guadalcanal=== |

|||

The Battle of Savo Island was the first of seven major naval actions during the Guadalcanal Campaign. In the Pacific War, the aircraft carrier replaced the battleship as the decisive weapon in naval warfare. The Americans initiated Watchtower with four fleet carriers. The Japanese entered the Guadalcanal Campaign with four fleet carriers and two light carriers. When the naval warfare off Guadalcanal ended, the only functioning American carrier in the South Pacific was ''USS Enterprise'' (CV-5). The Japanese lost only one light carrier sunk. Despite ending the campaign with more functioning carriers than the Americans, the Japanese were unable to press home this advantage because they had lost too many aircraft and experienced pilots in the Guadalcanal fighting. |

|||

===Japanese Army response to the Guadalcanal landings=== |

|||

By 10 August, Imperial General Headquarters was satisfied from the number of warships and transports off Guadalcanal and Tulagi that a full US Marine division had landed, but aerial and naval reconnaissance on 11 and 12 August disclosed only a few small boats between Lunga Point and Tulagi. The Japanese concluded erroneously that withdrawal of warships and transports signified that most of the marines had also been withdrawn after raiding Tulagi and Guadalcanal. There was nothing to suggest to Imperial General Headquarters at this stage that Japan was facing a major counter-offensive on Guadalcanal, and the stranded marines would be the beneficiaries of the initial muted Japanese Army response. |

|||

The capture of Port Moresby was still deemed to be Japan's highest priority in the South Pacific, and although the bulk of the Nankai Shitai and the 41st Regiment were still at Rabaul awaiting deployment to Buna, and then from Buna to the Kokoda Track, there was no thought of diverting these veteran combat troops to oust the marines from Guadalcanal. Instead, Lieutenant General Hyakutake's 17th Army was ordered to retake Tulagi and Guadalcanal with detachments that would be supplied to 17th Army for that purpose. Army General Staff decided that the 2000-man Ichiki Detachment would be sufficient to clear any remaining marines from Guadalcanal and Tulagi. Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki landed on the northern coast of Guadalcanal on 19 August with his First Echelon comprising 900 men. They launched an immediate frontal attack on the marines at Lunga Point and were effectively annihilated at the Ilu River. Colonel Ichiki committed suicide. |

|||

===Defeat of Kawaguchi Brigade compels downgrading of Port Moresby priority=== |

|||

Still unaware of the size of the marine force on Guadalcanal, 17th Army next committed Major General Kiyoyaki Kawaguchi's 6,200-man 35th Infantry Brigade to expel the marines from Henderson Field. In the Battle of Bloody Ridge on the night of 13-14 August, Kawaguchi's brigade was routed with very heavy casualties. Many of the survivors died from wounds, starvation, or disease as they battled dense jungle and rugged terrain to reach the Japanese enclave on the north-western corner of the island. |

|||

The Kawaguchi Force disaster on Guadalcanal had serious implications for Major General Horii who was fighting his way along the Kokoda Track to Port Moresby. Lieutenant General Hyakutake's 17th Army was conducting major operations simultaneously in Papua and Guadalcanal but lacked the troops and means to reinforce and sustain the two operations at the same time. With Horii in sight of searchlights probing the night sky over Port Moresby, a bitter decision had to be made. Imperial General Headquarters now realised that the Japanese were facing a major Allied counter-offensive on Guadalcanal, with a strategically vital airfield at stake, and switched priorities from Port Moresby to Guadalcanal. Horii was ordered to withdraw his troops from the Kokoda Track to the fortified beachheads and await another opportunity to capture Port Moresby after the marines had been expelled from Guadalcanal and Tulagi.<ref>McCarthy, p. 304; Griffith, pp. 126-127</ref> It would now become a battle of attrition on Guadalcanal, with victory likely to go to the side that could reinforce the fastest.<ref>Frank, p. 246</ref> |

|||

By mid-October 1942, the Japanese had concentrated some 20,000 troops on Guadalcanal. The next Japanese move against Henderson Field involved Major General Masai Maruyama's 2nd Division. Maruyama's troops battled dense jungle and heavy rain to reach the marine lines on the night of 23-24 October. After two nights of fierce fighting, the Japanese losses were so heavy that Maruyama abandoned the attack and led the survivors back to the Japanese enclave. |

|||

===Logistics defeat the Japanese on Guadalcanal=== |

|||

The Japanese moved reinforcements and supplies the 909 km (565 miles) from Rabaul to Guadalcanal at night by cruisers and destroyers. After delivering troops and cargo, the warships would shell Henderson Field before they departed. A major problem for the Japanese was the limited cargo capacity of warships and it was never possible to supply their troops on Guadalcanal with adequate rations and equipment. Slow moving transports were too vulnerable to attack by Allied aircraft, and by January 1943, the 20,000 Japanese troops on Guadalcanal were close to starvation. Under the cover of the Cactus Air Force and B-17s flying from New Hebrides and New Caledonia, and protected by the US Navy, the Americans could regularly bring in thousands of reinforcements and supplies during daylight hours for the depleted and exhausted 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal. |

|||

Appreciating that Japan faced inevitable defeat in the southern Solomons, Imperial General Headquarters ordered the evacuation of all Japanese troops on Guadalcanal. By 7 February 1943, the last of some 13,000 starving and disease ridden Japanese survivors had been withdrawn from Guadalcanal by sea. The Guadalcanal Campaign had ended, and with it, the threat of a Japanese blockade that had been intended to produce Australia's submission to Japan. |

|||

==Modern concept of a Battle for Australia== |

==Modern concept of a Battle for Australia== |

||

Revision as of 04:19, 13 March 2011

Template:Campaignbox Battle for Australia

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2009) |

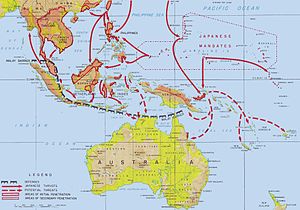

The term Battle for Australia is used to describe a series of battles near Australia during the Pacific War of World War II. These battles were fought between Allied and Japanese forces during 1942 and 1943, with the Allies seeking to stop a Japanese advance through the islands to the north of Australia which initially aimed to cut the shipping lines between the country and the United States and later sought to buttress Japan's defensive perimeter. The Japanese abandoned their offensive across the South Pacific to Fiji and Samoa as a result of carrier losses suffered in the Battle of Midway and a later attempt to capture the strategic town of Port Moresby was defeated during the Battle of Milne Bay and Kokoda Track campaign. Since 2008 these events have been commemorated by Battle for Australia Day, which falls on the first Wednesday in September.

Peter Stanley, the former principal historian at the Australian War Memorial, argues that the concept of a 'Battle for Australia' is mistaken as these actions did not form a single campaign aimed against Australia. Stanley has also stated that no historian he knows believes that there was a 'Battle for Australia'.[1]

Strategic importance of Australia in 1942

Following the outbreak of the Pacific War on 7 December 1941 Japan rapidly conquered much of Southeast Asia, defeating the Allies in the Battle of Malaya, Battle of Singapore, Dutch East Indies campaign and Philippines Campaign and a number of other battles between December 1941 and May 1942. Australian territory was attacked for the first time on 4 January when Japanese bombers struck Rabaul in the Territory of New Guinea and on the 23rd of the month Japanese troops landed near the town and captured it after defeating its Australian defenders in the Battle of Rabaul. On 19 February Japanese aircraft bombed Australian town of Darwin and the ships in its harbour in order to eliminate it as a base from which the Allies could contest the invasion of Timor which also began that day. This series of defeats greatly alarmed the Australian Government and Australian military. On 5 March 1942 Major General Sydney Rowell, the Deputy Chief of the Army's General Staff, provided the government with an assessment that the Japanese could attack the strategic town of Port Moresby in the Territory of Papua in March followed by landings at Darwin and New Caledonia in April and the Australian east coast in May. The US Army high command in Australia estimated that a landing in Darwin could take place in March.[2] Three days later Japanese troops landed on the mainland of New Guinea and captured the small towns of Lae and Salamaua.

During late 1941 and early 1942 the Japanese military considered an invasion of Australia but decided on a strategy of isolating the country instead. Japanese strategic military policy with regard to Australia was decided at the highest level on 10 January 1942 when the Imperial Headquarters-government liaison conference resolved to "Proceed with the southern operations...blockading supply from Britain and the United States and strengthening the pressure on Australia, ultimately with the aim to force Australia to be freed from the shackles of Britain and the United States."[3] The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) believed that Australia could become a base from which the Allies could launch a counter-offensive, and proposed invading the country with relatively small forces during conferences held in December 1941 and February 1942. The Imperial Japanese Army believed that the Navy's estimate of the force needed for an invasion of Australia was much too low given the estimated strength of the Allied forces in the country and that sufficient troops and the shipping needed to carry an them to Australia were not available. As a result, on 28 February 1942 the Japanese Government formally adopted the objective of cutting Australia off from the United States, Britain and India by capturing Fiji, New Caledonia, Samoa in the Pacific (Operation FS) and Ceylon in the Indian Ocean.[4] This was to be accorded the highest priority as isolating Australia was seen as being critical to Japan dominating the Southwest Pacific".[5] On 4 March the Imperial General Headquarters formally agreed to a "Fundamental Outline of Recommendations for Future War Leadership" which relegated the option of invading Australia as a "future option" to be carried out only if all other plans went well, and this was endorsed by Emperor Hirohito on 13 March. This was in accordance with the views of Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō, who always opposed invading Australia and strongly supported Operation FS as a means of forcing Australia to submit to Japan by intensified blockade and psychological warfare.[6]

For their part, the Americans were not obliged by treaty to defend Australia. The Arcadia Conference held in Washington in late December 1941 obliged the United States and Britain to give the highest priority to defeating Nazi Germany. Arcadia relegated all of the Pacific region west of Hawaii to the status of a secondary theatre of war.[7][8] The Commander in Chief US Navy, Admiral Ernest J. King, believed that the United States should not allow Japan to seize or control Australia and the islands between Australia and Hawaii because the United States would need access to Australia and Guadalcanal as bases for a counter-offensive to recover the Philippines. King's strategic views were incorporated in the US Navy's "Pacific Ocean Campaign Plan".[9] Without specifically mentioning Australia, he insisted that the vaguely worded Arcadia Agreement include words that would allow the United States to defend areas in the Pacific that were necessary "to safeguard vital interests".[10] The words "vital interests" were not defined, and King argued successfully for inclusion in the agreement of words that authorized the seizure of "vantage points" from which a counter-offensive against Japan could be developed.[11] Having set the stage for a clash of Japanese and American strategies focussed on Australia and Guadalcanal, King moved to place US Marine and Army garrisons on key islands forming the chain between Australia and Hawaii.[12][13] King also felt that he had acquired authority to defend Australia by placing his fleet carriers between the Japanese advance and Australia. The USS Lexington (CV-2) was deployed for this purpose in February 1942 to attack the newly acquired Japanese base at Rabaul.[14] King's allocation of American military resources to defend Australia was strongly opposed by the US Army Staff. General Henry H. Arnold told the Joint Chiefs of Staff on 16 March 1942 that an all-out effort to defeat Nazi Germany required sending no reinforcements to the Pacific "even if this meant accepting the loss of Australia".[15] The US Army's attempted abandonment of Australia was countered by the "Pacific First" lobby on Capitol Hill, and American public and press support for General Douglas MacArthur who arrived in Australia on 17 March 1942 from the Philippines to take command of Allied forces in the South West Pacific.[16]

Curtin finds Australia ill-prepared for war with Japan in January 1942

When John Curtin took office as Australia's prime minister in October 1941, he was well aware that Australia was ill-prepared for war if Japan chose to launch a war against the United States and seize the resource-rich colonial possessions of the British and the Dutch in South-East Asia. Three well-trained AIF divisions (the 6th, 7th and 9th) were fighting in the Middle East and North Africa. Two brigades of the AIF 8th Division were stationed in Singapore for its defence. The three battalions of the third 8th Division brigade were deployed across the northern approaches to Australia at Rabaul, Timor, and Ambon in December 1941. At the outbreak of the Pacific War on 7 December 1941, the Australian military units in Australia were weak; the Army forces comprised eight partially trained and inadequately equipped militia divisions, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) had 373 aircraft, most of which were obsolescent Wirraway trainers, and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) had three cruisers and two destroyers under British command in Australian waters.[17] To compound Curtin's problems in mounting a defence against Japanese aggression, the Menzies government had agreed in December 1939 to provide Britain with 28,000 Australian trainee pilots and aircrew for service with the Royal Air Force under the Empire Air Training Scheme. By late December 1941, Curtin had become convinced that Australia could not rely on Britain alone to ensure Australia's survival against Japan. In his famous radio broadcast of 26 December, Curtin declared: "I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom."[18] Although the declaration caused a sensation in London and Washington at the time, it helped to persuade the United States to send two army divisions to defend Australia.

Forces for the defence of Australia remained inadequate in March 1942, though part of the 6th Division and all of the 7th Division returned to Australia from the Middle East during that month. These AIF units were veterans of combat against Germany, Italy and Vichy France. United States General Douglas MacArthur also arrived in Australia during March and assumed command of all Allied units in the South-West Pacific Area. In order to defend against the feared invasion Australian and United States Army forces were deployed along Australia's east coast and air units were concentrated between Townsville and Cloncurry from where they could attack Rabaul.[19] It was intended that reinforcements would be sent to New Guinea as soon as trained forces were available and could be supplied there.[20] The Allies had broken Japan's naval communications code JN25, and in April, intelligence from this source collected by the US Navy's Fleet Radio Unit in Melbourne FRUMEL alerted them to the planned Japanese offensive into the South Pacific. On 18 April the Allies intercepted a Japanese diplomatic cable (though the "MAGIC" codebreaking effort) which stated that there was no plan to invade Australia. On the same day the United States Pacific Fleet's intelligence staff also concluded that Japan did not intend an invasion, and MacArthur told Australian Prime Minister John Curtin on 23 April that while Japan might land raiding forces, a major attack was unlikely. Despite this Curtin stated in a speech on 29 April that the Australian Government believed that there was "a constant and undiminished danger" of invasion and that Japan might attempt to isolate Australia as a precursor to this.[21]

Battle of the Coral Sea

The capture of Port Moresby on the southern coast of the Australian Territory of Papua was a vital feature of Operation FS. The Japanese intended that Port Moresby would be the anchor for a chain of Japanese bases that would stretch across the South Pacific to Fiji and Samoa and isolate Australia from the United States. Behind a barrier of captured and fortified Japanese island bases, it was intended that Australia would be blockaded and pounded into submission to Japan. See Frei at page 172.

The Battle of the Coral Sea (7–8 May 1942) resulted from Japan's first attempt to capture Port Moresby by a seaborne invasion force. Although part of the broader Operation FS, the capture of Port Moresby was assigned the specific code reference Operation Mo. A smaller operation undertaken at the same time as the Port Moresby operation was the capture of the island of Tulagi in the British Solomons on 3 May 1942. The Japanese intended to establish a forward seaplane base at Tulagi which was only defended by a very small Australian force. After first capturing Tulagi, the Japanese moved their invasion transports towards Port Moresby under the protection of one light carrier Shoho and two large fleet carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku. It was intended that the two Japanese fleet carriers would guard the invasion force against intervention by American carriers and, after doing so, proceed south to attack military targets on the Australian mainland.

Forewarned by American and British code-breakers of this Japanese plan to capture Port Moresby, a combined American and Australian naval force prepared to intercept the Japanese invasion fleet. While an Australian-American cruiser squadron stood off the southern tip of Papua to block the movement of the invasion transports through the Jomard Passage and towards Port Moresby, the American fleet carriers Lexington and Yorktown sank the escorting Japanese light carrier Shoho on 7 May 1942. On the following day, 8 May, the American carriers engaged the two Japanese fleet carriers in the Coral Sea. Lexington was hit by two air-launched torpedoes, and caught fire and sank after the battle. Yorktown was hit by one bomb that exploded deep inside the carrier and caused serious damage. Although Yorktown was still operational, Rear Admiral Fletcher decided to withdraw his carrier group from the Coral Sea but not the Australian-American cruiser squadron blocking the path of the invasion transports towards Port Moresby. Battle damage inflicted on the two Japanese fleet carriers forced their withdrawal from the Coral Sea. With the Australian-American cruiser squadron still blocking the approach to Port Moresby, and no carriers left to cover the landing at Port Moresby, the Japanese felt compelled to withdraw their Port Moresby invasion force to their base at Rabaul. The Japanese decision to withdraw their invasion force was partly influenced by air reconnaissance which mistakenly identified the Australian-American cruiser squadron as comprising "one carrier, one battleship, two heavy cruisers, and nine destroyers".[22][citation needed]

The Allied strategic victory over the Japanese in the Battle of the Coral Sea preserved Port Moresby as the main Allied forward base on the island of New Guinea; it denied the Japanese their anchor for Operation FS; it denied the Japanese the Coral Sea as a barrier to protect their captured bases on the island of New Guinea; and it denied the Japanese a base from which their bombers could range as far as 1,600 km (1,000 miles) into the Australian mainland and across the Coral Sea. Another very important aspect of this naval battle was the damage caused to the Japanese fleet carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku. That damage prevented their participation in the crucial Battle of Midway in early June 1942 where their presence could have changed the course of that battle significantly.[20] Despite the Japanese defeat in the Battle of the Coral Sea, Prime Minister Tōjō threatened the Australian Government during a speech to the Japanese Diet on 28 May, stating that it still was not too late for it to submit to Japan.[23]

Battle of Midway and afterwards

In the Battle of Midway (4–6 June 1942), the IJN fleet carriers Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, and Soryu were destroyed in the course of a major Japanese offensive against Midway Atoll in the Central Pacific. This massive defeat at Midway demolished Japan's clear naval superiority over the US Pacific Fleet. On 26 June MacArthur told Curtin that "the security of Australia had been assured" by the American victory in the Battle of Midway. MacArthur and the Allied South Pacific Area command also began preparations for major offensive against Rabaul, which was to include landings in the Solomon Islands.[24]

Accepting that Japan no longer possessed the ability to project naval power across the Pacific as far as Fiji and Samoa, Imperial General Headquarters cancelled Operation FS on 11 July 1942,[25] but did not shelve Operation FS completely[26] and aerial reconnaissance of New Hebrides, New Caledonia, and Fiji continued from the Japanese airbase at Tulagi in the British Solomons.[27] At this time the headquarters hoped to be able to launch Operation FS in November 1942, though the IJN was not confident of being able to blockade Australia through such an offensive. By August the date at which Operation FS was to be launched had been advanced to September and Japanese forces landed on the island of Guadalcanal to build an airfield to support this.[28]

The capture of Port Moresby would be given the highest priority to remove the main Allied base on the island of New Guinea from which Allied bombers could strike at Japan's newly acquired bases in Australia's New Guinea Mandate. Capture of Port Moresby would create the additional barrier of a 500 km (310 mile) stretch of the Coral Sea between any Allied forward base on the Australian mainland and Japanese bases on the island of New Guinea. In Japanese hands, Port Moresby would provide the anchor for a chain of Japanese bases that would no longer extend further east than the island of Guadalcanal in the British Solomons; but with the whole of the island of New Guinea and the British Solomon Islands under Japanese control, forward naval and air bases could be established on these territories from which the Japanese could strike deeply into the Australian mainland and hinder military support for Australia from the United States. A number of less ambitious plans were developed to achieve these strategic objectives.

The Japanese Navy General Staff authorized Operation SN to strengthen Japan's outer defensive perimeter by constructing forward airbases at key strategic locations in Australia's Territory of Papua and the British Solomon Islands. On 13 June 1942, the Japanese Navy General Staff approved construction of a forward airbase at Lunga Point on the northern coast of the island of Guadalcanal. A 48 km (30 mile) stretch of sea separated the Japanese seaplane base at Tulagi from Lunga Point. On 29 June 1942, about two thousand Japanese troops and workers landed at Lunga Point where they began construction of a strategically vital airfield (later to be known famously as Henderson Field). When completed, this forward airbase would enable Japanese bombers to range far across the Coral Sea and bomb Allied staging bases on New Hebrides and New Caledonia. This Japanese threat to lines of communication with Australia caused deep concern to the Commander in Chief United States Navy, Admiral Ernest J. King, who believed that the United States needed to preserve access to Australia as a major base for an American counter-offensive to recover the Philippines from Japanese occupation.

Kokoda Campaign

Japanese Army considers an overland attack on Port Moresby using the Kokoda Track

Acknowledging the weakened operational capabilities of the Japanese Navy after Midway, Imperial General Headquarters transferred primary operational responsibility for capturing Port Moresby to Japan's 17th Army commanded by Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake. The Imperial Navy would take a supportive role. The Japanese high command now wanted to explore the possibility of capturing Port Moresby by using the Kokoda Track to cross the Owen Stanley Range which separated the northern and southern coastal plains of Papua. General Hyakutake was ordered to examine the feasibility of an overland attack on Port Moresby. Studying maps in Tokyo, the task may have appeared deceptively easy to the army planners. The distance in a straight line from Buna and Gona on the northern coast of Papua to Port Moresby on the southern coast was only about 160 kilometres (100 miles) but to reach Port Moresby Japanese troops would have to cross some of the world's most rugged and unforgiving terrain.

It is unlikely that the army planners in Tokyo had any appreciation of the daunting conditions that their troops would face when crossing the Owen Stanleys. The Kokoda Track was a narrow and mostly single file path beaten out of the forest and bush by the tread of native feet over millenia. It stretched for 96 kilometres (60 miles) from Owers' Corner on the southern foothills of the Owen Stanley Range to the small government post at Kokoda on the northern foothills. There was no settlement at Owers' Crossing; it simply marked the point at which the ruggedness of the terrain prevented motor vehicles proceeding further towards Kokoda.

The Japanese and Australian troops faced the same conditions on the Kokoda Track, which have been described with reference to the Australians: "..conditions on the Kokoda Track were appalling. The narrow dirt track climbed steep heavily timbered mountains, and then descended into deep valleys choked with dense rain forest. The steep gradients and the thick vegetation made movement difficult, exhausting, and at times dangerous. Razor-sharp kunai grass tore at their clothing and slashed their skin...daily rainfalls of 25 centimetres (10 inches) are not uncommon (on the Kokoda Track). When these rains fell, dirt tracks quickly dissolved into calf-deep mud which exhausted the soldiers after they had struggled several hundred metres through it...Sluggish streams in mountain ravines quickly became almost impassable torrents when the rains began to fall....Heat, oppressive humidity, mosquitos and leeches added to the discomfort of the rain-drenched Australian soldiers...their other deadly enemy was disease. Malaria, dengue fever, scrub typhus, and dysentery flourished in these conditions and added to the misery of the exhausted Australians. Wet clothes and boots were a frequent source of unpleasant skin diseases." From "Battleground New Guinea and its Defenders" by James Bowen (2001).

Intelligence warnings alert General MacArthur to the need to defend Kokoda

The American Supreme Commander South-West Pacific, General Douglas MacArthur, and the Australian Commander Allied Land Forces, General Sir Thomas Blamey, had been warned by American naval intelligence in Melbourne (FRUMEL) in early June 1942 that the Japanese were likely to attempt an overland attack on Port Moresby, but neither commander was unduly alarmed. They did not believe that a Japanese army could cross the rugged Owen Stanleys and threaten Port Moresby. However, the potential threat to the strategically important Kokoda airstrip on the northern slopes of the Owen Stanleys could not be ignored. On 20 June 1942, General Blamey ordered the army commander at Port Moresby, Major General Morris, to secure Kokoda with its vital airstrip. At this time, Port Moresby was defended by three Australian militia infantry battalions. The average age of these citizen soldiers was eighteen and a half. They were inadequately trained and poorly equipped for battle. Their lack of military training is explained by the fact that they were mostly employed at Port Moresby as labourers. This demoralising employment and lack of proper military training caused the three militia battalions defending Port Moresby to be assessed at the lowest level of combat efficiency, and they still carried this low "F" rating when the Japanese invaded Papua.

On 24 June, Major General Morris ordered the 39th Australian Infantry Battalion to cross the Owen Stanleys with the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB) and secure Kokoda. It was necessary to send these undertrained and poorly equipped citizen soldiers to defend Kokoda because Australia's top military commanders were employing only militia units to defend the vital northern gateway to Australia and retaining the combat veterans of the 7th Division in Australia to defend the mainland against a possible Japanese invasion. The 39th Battalion was a fortunate choice to defend Kokoda because it included a substantial component of veteran regular army officers and NCOs. The PIB was a force of about 280 native soldiers led by 30 Australian officers and NCOs. The ruggedness of the terrain and narrowness of the Kokoda Track required the soldiers to move for most of the arduous trek in single file, and companies would move in stages to reduce serious supply problems while on the track. The first company of the 39th Battalion to move into the Owen Stanleys on 8 July 1942 was B Company, numbering about 100 officers and men in three platoons. C Company would follow on 23 July. Major General Morris did not believe that mortars could be effective in heavily forested mountains like the Owen Stanleys, and allowed these militia companies to be equipped only with rifles, hand grenades, and light machine guns. The Japanese had no such reservations about the use of mortars and readily dismantled light artillery in forested mountains, and it would give them a deadly edge over the Australians on the Kokoda Track.

B Company of the 39th Australian Infantry Battalion reaches Kokoda

By 15 July, B Company troops had reached Kokoda. Their commander Captain Sam Templeton left one platoon to defend Kokoda and then set out with two of his platoons to patrol towards Buna on the northern coast. The commander of the PIB Major Watson split his battalion with about half patrolling between Kokoda and Awala, a small village located about half way between Kokoda and Buna, and the other half patrolling a large area north-west of Buna.

Japanese invade Papua

On 21 July 1942 about 2,000 Japanese troops of the Yokoyama Advance Force landed at Gona and Buna on the northern coast of the Australian Territory of Papua. This advance force was commanded by Colonel Yosuke Yokoyama and included a large part of his 15th Independent Engineer Regiment. The engineers had been ordered to convert the Japanese beachheads at Gona and Buna into a massive linked and heavily fortified base capable of supporting a much larger force. The advance force also included the Tsukamoto Battalion drawn from the Nankai Shitai's 144th Infantry Regiment and a company of the elite 5th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF). The jungle-trained Nankai Shitai combat veterans and the naval assault infantry were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Hatsuo Tsukamoto who was under orders to move quickly to capture Kokoda with its strategically important airstrip and clear a path to the Kokoda Track for the rest of the Nankai Shitai (South Seas Detachment) if Colonel Yokoyama deemed it feasible for a Japanese army to reach Port Moresby by crossing the Owen Stanley Range. As soon as his combined force of about 1,000 troops had landed, Tsukamoto led his men off the beach and along the narrow track leading to Kokoda. It was a formidable force. In addition to light arms, these Japanese assault troops were equipped with mortars, heavy machine guns, and light mountain artillery.

When news of the Japanese invasion of Papua reached Port Moresby, General Morris ordered the commander of the 39th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Owen, to fly to Kokoda on 23 July to command the 39th Battalion and the Papuan Infantry Battalion which were now designated Maroubra Force.

Australians stage a fighting withdrawal to Kokoda

The first contact between the Australians and the Tsukamoto Force occurred on 23 July near Awala, a village located about half way between Gona/Buna and Kokoda. A lightly armed forward PIB patrol engaged the advancing Japanese but was quickly routed when the Japanese responded with mortar, heavy machine guns, and artillery. Aware that they were facing a formidable Japanese force that greatly outnumbered them and had heavier weapons, the only option available to the Australian force was a fighting withdrawal to Kokoda.

Japanese high command resolves to implement a two-pronged attack on Port Moresby

During the days following the Japanese landings in Papua, Colonel Yokoyama reported his belief that a Japanese army could reach Port Moresby by means of the Kokoda Track. Responding to this news, Imperial General Headquarters ordered Lieutenant General Hyakutake on 28 July to prepare for the overland attack on Port Moresby which was reinstated as Operation MO and a simultaneous attack on the Allied airbase at Milne Bay on the eastern tip of Papua with the code reference Operation RE. The rest of the Nankai Shitai, supported by the 41st Infantry Regiment (Yazawa Force), would deploy to Papua and follow the Tsukamoto Force to the Kokoda Track. Major General Tomitaro Horii would command his own Nankai Shitai and the 41st Infantry Regiment for the attack on Port Moresby. The Japanese high command envisaged that Horii's force would emerge from the Kokoda Track and be supported in its attack on Port Moresby by Japanese aircraft flying from the captured Allied base at Milne bay.

Japanese capture Kokoda on 29 July 1942

With a mixed force of about eighty 39th Battalion and native troops, Lieutenant Colonel Owen prepared to defend Kokoda and its vital airstrip. He contacted Port Moresby by radio on 28 July and requested reinforcements and mortars. During the day two transport aircraft loaded with Australian troops and mortars circled the airstrip and then departed to the astonishment of the defenders. After nightfall on 28 July, hundreds of assault troops from the Tsukamoto Force swarmed over the Kokoda plateau. The Australians were quickly overwhelmed and Kokoda was captured in the early hours of 29 July 1942. Owen was killed in the attack and Australian survivors escaped through the rubber plantation to Deniki.

39th Battalion recaptures Kokoda and loses it again

In the week following the Japanese capture of Kokoda, more companies of the 39th Battalion arrived at Deniki. By 6 August, the 39th Battalion could muster a strength of 31 officers and 433 men. Also at Deniki were 35 native soldiers and 8 European officers and NCOs of the Papuan Infantry Battalion, and 14 native police. Major Allan Cameron arrived to take temporary command of Maroubra Force and was keen to stage a counter-attack to recapture Kokoda. His company commanders voiced their objections to Cameron's plan on the grounds that they had no clear intelligence regarding the size of the Japanese force or its dispositions in and around Kokoda. Brushing aside their reservations, Cameron dispatched three companies by separate routes to Kokoda on 8 August. The counter-attack proved to be a disaster for the 39th Battalion. C and D Companies met overwhelming opposition and the Japanese pursued them aggressively back to Deniki. Captain Symington's A Company reached and captured Kokoda, but was forced to withdraw on 10 August after heavy fighting. The exhausted survivors of A Company retreated by a roundabout route to the village of Isurava located on the first mountain ridge beyond Deniki.

Nankai Shitai arrives in Papua

With Kokoda now firmly under Japanese control, and the Kokoda Track now appearing to be open for the passage of a Japanese army, the main body of the Nankai Shitai embarked at Rabaul for Buna on 17 August 1942. The Nankai Shitai was closely followed by two battalions of the Yazawa Force which landed at Buna on 21 August. The continuing Japanese troop build-up in the Gona-Buna-Kokoda triangle had now reached 13,500 troops, and 10,000 of these were tough, jungle-trained combat veterans. From these troops, Major General Tomitaro Horii, commander of the Nankai Shitai (South Seas Detachment) and 41st Infantry Regiment, could draw a well-balanced fighting group [reference] which included six infantry battalions, mountain artillery, and engineers, for the overland attack on Port Moresby.

Battle of Isurava

At Deniki, Major Cameron's 39th Battalion now comprised only E Company and the exhausted and depleted C and D Companies. The Japanese attacked in strength on 13 August and on the following day, when the Japanese were pushing into the Australian positions, Cameron felt obliged to withdraw the remnant of his battalion to the village of Isurava on the first ridge above the northern foothills.

The men of the 39th Battalion dug in at Isurava. They were buoyed by the arrival of their new commander Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner on 16 August. His orders were to hold Isurava until relieved by veteran AIF units of the 21st Brigade which were then preparing to move up the Kokoda Track from Port Moresby. Honner found his men in poor shape and quickly set to work building up morale and deploying his depleted battalion as effectively as possible. He knew that if the Japanese broke through quickly at Isurava they would catch the AIF battalions at a grave disadvantage while strung out along the Kokoda Track. If this happened, it was likely that the Japanese would achieve the momentum that would enable them to reach Port Moresby.

Major General Horii launched his attack on Isurava on 26 August. This attack was timed to coincide with an attack on the Allied airbase at Milne Bay which was the second prong of the Japanese attack on Port Moresby. Outnumbered by at least ten to one, the Australian militia troops stood firm. By mid-afternoon on that day companies of the AIF veterans of the 2/14 Battalion began arriving to relieve the 39th Battalion. The 39th Battalion declined to be relieved, and stayed at Isurava to support the 2/14th Battalion as a reserve force.

In the great battle that took place at Isurava over four days from 26 to 29 August 1942 the Australians withstood repeated Japanese human wave attacks supported by mortar bombardment and mountain artillery. Major General Horii knew that the Australians were heavily outnumbered and he was prepared to sacrifice a large number of his troops to overrun the Australian defensive positions. By sheer weight of numbers, the Japanese finally penetrated the Australian lines and occupied the vital high ground on the western side of the Australian defensive perimeter. From this high ground, the Japanese were able to rake the Australian defenders with heavy machine gun fire. The commander of the 2/14th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Keys, realised that the position of the Australians at Isurava had become untenable in the face of overwhelming enemy numbers and the loss of the western high ground. Keys sought and received permission to withdraw from Isurava and set up a new defensive position further down the Kokoda Track.

Japanese defeat at Milne Bay

At Milne Bay the Australians and Americans had been developing a forward airbase since June 1942. Capture of Milne Bay would have provided the Japanese with an airstrip from which Major General Horii's attack on Port Moresby could be supported by Japanese aircraft when his troops emerged from the southern end of the Kokoda Track.

Timed to coincide with the Japanese attack at Isurava, on the night of 25–26 August 1942 the second stage of the overland Japanese offensive against Port Moresby was launched when 2,400 naval infantry, including the elite 5th Kure SNLF and the 5th Sasebo SNLF (Special Naval Landing Force) were landed at Milne Bay on the eastern tip of Papua in heavy rain. The Japanese light tanks were quickly bogged in the deep mud. After ten days of very heavy fighting, and hampered by heavy rain, mud, and communication difficulties, Australian troops and aircraft forced the Japanese invaders to withdraw on 5 September 1942. For the first time in World War II, a Japanese invasion force had been driven back into the sea.

Major General Hori's drive towards Port Moresby defeated by a stubborn Australian fighting withdrawal

Despite being forced to withdraw, the Australian defence of Isurava had sown the seeds of Major General Horii's ultimate defeat. Although continuing to suffer very heavy losses, the Australians staged a fighting withdrawal lasting almost four weeks across the Owen Stanleys from Isurava to Imita Ridge on the mountains overlooking Port Moresby. At Ioribaiwa, on 25 September 1942, the Japanese drive towards Port Moresby finally ran out of steam. In their fierce determination to overcome the Australians, the Japanese had sustained nearly 3,000 battle casualties on the Kokoda Track. With Horii's supply lines in chaos, and his troops starving and exhausted, Japan's Imperial General Headquarters acknowledged defeat on the Kokoda Track. Horii was ordered to withdraw his battered army to the Japanese beachheads at Gona-Buna. A savage war of attrition between the Americans and Japanese over possession of the strategic island of Guadalcanal in the British Solomons had deprived the Japanese of the capacity to reinforce Horii's troops for the final 40 km (25 mile) push to Port Moresby.

Strategic significance of Isurava

Between 26 and 30 August 1942, several hundred Australian soldiers defended the Kokoda Track at Isurava against 5,000 of Japan's best combat troops. The Australians were heavily outnumbered, inadequately armed, and poorly supplied, but their resolute stand over those four days at Isurava inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese and blunted the momentum of Major General Horii's drive towards Port Moresby. The stubborn resistance of the Australian troops at Isurava wrecked the Japanese timetable for crossing the Kokoda Track, gave time for Australian AIF reinforcements to be brought up, and laid the foundation for the ultimate defeat of Horii’s army before it could reach Port Moresby.

Battle of the Beachheads - Gona, Buna and Sanananda

Major General Horii's retreating army was closely pursued along the Kokoda Track by fresh troops of Australia's 25th Brigade. The Australians were more than half way to Kokoda before they overtook the Japanese rearguard well dug in on the track near Templeton's Crossing on 8 October. After a week of heavy fighting, the pursuit continued with the fresh 16th Brigade moving to the front and attacking the Japanese at Eora Creek where they had established a strong defensive position on a steep rise above the creek. After more heavy fighting, the Japanese were routed and Australian troops recaptured Kokoda on 2 November. With the vital Kokoda airstrip recovered, the Australian supply problem was solved. The Japanese had established a strong defensive position at Oivi on the coastal plain below Kokoda. After six days of heavy fighting, the Japanese resistance crumbled and survivors fled into the bush on 11 November. The track to Gona and Buna now lay open to the Australians with only the wide and swift-flowing Kumusi River to cross. The Kumusi had been a fatal obstacle to Major General Horii who drowned when his log raft overturned. The campaign in the Owen Stanleys to defend Port Moresby had lasted almost four months, and had cost the Australians 625 killed and 1055 wounded.[29]

When General MacArthur realised that the Japanese threat to Port Moresby had been lifted by Australian troops on the Kokoda Track, he felt that it was important to involve American troops in the battle to expel the Japanese from their beachheads on the northern coast of Papua. In the mistaken belief that General Horii’s retreating troops were beaten, and that only a couple of thousand starving and exhausted survivors of the Kokoda Track would have reached the Japanese beachheads, General MacArthur ordered an assault by Australian and American troops on the beachheads that stretched for 16 km (10 miles) from the village of Gona, past Sananada Point, to the village of Buna. The veteran Australian 16th and 25th Brigades would attack Gona and Sanananda. The untested former National Guardsmen of the American 32nd Division were assigned the task of capturing Buna.

Unknown to General MacArthur, the Japanese had turned the beachhead villages into heavily fortified strongholds and had poured in thousands of fresh troops. MacArthur's mistake would produce a very heavy cost in Australian and American lives. With the sea on one side, and mostly protected by fetid and malaria-infested swamp and sago palms on the landward side, nine thousand Japanese troops had prepared cleared fields of fire to expose the advancing Australian and American troops. From their camouflaged bunkers, trenches, and sniper positions, the Japanese took a heavy toll on the Australians and Americans advancing through the swamps. Each bunker had to be demolished before Allied troops could advance to the next Japanese strong point.

The Australian 25th Brigade, already depleted by at least one third by heavy fighting on the Kokoda Track and disease, directed its attack against Gona on 18 November. Repeated attacks on the fortified Japanese positions were repulsed with heavy losses, and on 28 November the heavily depleted and exhausted 25th Brigade was withdrawn and replaced by the fresh 21st Brigade. Now supported by aerial bombardment, and heavy artillery and mortar fire, the 21st Brigade captured Gona on 9 December.

The American 128th Regiment approached Buna under the misconception that it would be little more than a mopping up operation. Unsupported by tanks or heavy artillery, and lacking training for an assault through swamp on strongly defended bunkers, the concentrated Japanese fire on the ragged American lines produced massive casualties and an effective American withdrawal from the assault on Buna. When MacArthur heard that the Australians were still engaged in heavy fighting for Gona and that the American assault on Buna was at a standstill, he replaced the commander of the 32nd Division, Major General Harding with Lieutenant General Eichelberger. Bringing in heavy artillery and tanks, and with the support of the fresh Australian 18th Brigade, Eichelberger revitalized the American attack and Buna was captured on 2 January 1943.

Colonel Yokoyama had established his headquarters at Sanananda with a mixed force of about 5,500 troops including the remaining strength of the Nankai Shitai and 41st Infantry Regiment.[30] Under attack by both the Australians and Americans, Sanananda held out until 21 January 1943 when the surviving Japanese were ordered to break out westwards and await rescue by launches.[31] When the Australians moved into Sanananda on 22 January, they found only dead, very sick, and seriously wounded Japanese.

Cost of the Kokoda Campaign

The Japanese Kokoda Campaign ended in defeat on 22 January 1943 after six months of some of the bloodiest and most difficult land fighting of the Pacific War. Australia lost 2,165 troops killed and 3,533 wounded. The United States lost 671 troops killed and 2,172 wounded. Of the near 20,000 Japanese troops landed in Papua, it is estimated that the Japanese lost about 13,000.[32]

Guadalcanal Campaign

Main article: Guadalcanal Campaign

Establishment of a major forward airbase on the northern coastal plain of Guadalcanal at Lunga Point was a vital aspect of the Japanese strategic plan to isolate Australia from the United States by a tightening blockade that Japan's military leaders believed would be capable of producing Australia's submission to Japan. Vital American staging bases between Hawaii and Australia were located on both New Hebrides and New Caledonia, and a Japanese airbase on Guadalcanal would bring those American staging bases within the operational striking range of Japan's bombers.[33]

US Navy acts to block an operational Japanese airbase on Guadalcanal

On 6 July 1942, 2,500 Japanese troops and construction workers landed at Lunga Point on the northern coast of Guadalcanal on 6 July 1942 to begin construction of a strategically vital airfield (later to be known famously as Henderson Field). When the Commander in Chief US Navy, Admiral King, learned of this alarming development, he resolved to make the Japanese tenure of the airfield on Guadalcanal a brief one.[34]

Preparations for an Allied offensive through the Solomons to recapture Rabaul, code name "Watchtower", had been in progress since 14 June when advance elements of the 1st Marine Division landed in Wellington New Zealand. The initial objective of Watchtower (Task 1) had been recovery of Tulagi which had been captured by the Japanese on 3 May 1942. When Admiral King learned that the Japanese were building an airfield on Guadalcanal that threatened lines of communication with Australia, he added capture of that airfield (operation code name "Cactus") to the Tulagi operation.[35] The D day for Task 1 was fixed for 1 August 1942.

The Japanese were planning to land their first aircraft at Lunga Point on 16 August.[36], and the planning, preparation, and coordination of this complex operation was necessarily rushed to ensure that the American amphibious force was not exposed to the serious threat from a fully operational Japanese airbase on Guadalcanal. Fragmented command and failure to plan for and provide efficient and coordinated communications would imperil Task 1 from the first day.[37] Acknowledging these difficulties, Admiral King extended D day for Task 1 to 7 August.[38]

Acrimonious pre-landing conference of senior commanders

Senior Watchtower Task 1 tactical commanders held their only pre-landing conference at Fiji.[39] Present at this conference were the Expeditionary Force commander Vice Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, Amphibious Force commander, Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, Air Support Force commander Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes, water-and land-based aircraft commander Rear Admiral McCain, Screening Group commander Rear Admiral Victor A. C. Crutchley, VC, RN and Landing Force commander Major General Vandegrift.

The meeting started badly when Fletcher announced his lack of confidence in the success of the Task 1 operation and became acrimonious when he declared his intention to withdraw his carriers after two days to avoid air counter-attacks and refuel his ships.[40] Turner protested that he would need five days to land his troops and their supplies and equipment. When Vandegrift added his protest that Fletcher's withdrawal of carrier support after two days would leave the landing force dangerously exposed to Japanese air and naval attack, Fletcher was only prepared to extend carrier covering support to three days.[41]

American landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi on 7 August 1942

The Japanese were taken by surprise when the American amphibious force arrived off Lunga Point and Tulagi at daybreak on 7 August 1942. Navy guns and aircraft pounded both bases before the marines landed. Four rifle battalions (about 3,000 marines) landed at Tulagi. Vandegrift personally led the landing at Lunga point with 11,300 marines.[42] The 2,571 Japanese at Lunga Point were garrison and construction troops, and they fled into the jungle when the marines advanced on the airfield leaving behind massive quantities of undamaged equipment and supplies. The 863 Japanese on Tulagi included elite naval troops of the 3rd Kure SNLF.[43] It required very heavy fighting before the marines captured Tulagi and the nearby fortified islands of Gavutu and Tanambogo.

Aust Coastwatchers provide vital warnings of Japanese air attacks

At Rabaul, the Japanese heard of the American landings by radio at 0652 hrs, and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto at Truk ordered a "decisive counter-attack".[44] Bombers being prepared for an air raid on Milne Bay were diverted to Tulagi and Guadalcanal and 27 took to the air at 0930. At 1030 the Japanese bombers and their 18 Zero escorts were sighted by Australian coastwatcher Paul Mason from one of his observation posts on the mountains of Japanese-occupied Bougainville. Mason's radio warning from Bougainville was transmitted when the Japanese formation was still 560 km (350 miles) from Guadalcanal.

Ship-mounted radar might have provided the Americans with 10 to 20 minutes warning of the approaching Japanese strike formation, but that would not have given the anchored transports time to discontinue unloading and disperse. If caught at anchor and unloading, the transports would have been highly vulnerable to air attack. Such short notice would not have given Wildcat fighters on the American carriers cruising south of Guadalcanal time to reach appropriate interception height. The radio warning from Mason gave the American transports time to raise anchor and disperse, and time for the American carrier-launched fighters to reach appropriate interception height. Seven Japanese aircraft were shot down. The only damage to the American invasion force was minor damage to the destroyer USS Mugford. Later that same day, Mason gave timely radio warning of an approaching formation of nine Aichi dive-bombers. None returned to Rabaul and no ship was damaged.

On the following day, Australian coastwatcher Jack Read on Bougainville reported a formation of 27 torpedo-equipped bombers with 15 Zero escorts heading for Guadalcanal. The timely warning again enabled the transports to halt unloading and disperse. One transport and one destroyer were heavily damaged. Most of the low flying torpedo bombers were destroyed by anti-aircraft fire.

Without these timely radio warnings from the Australian coastwatchers, the success of the American landings could have been seriously jeopardised. Vice Admiral William F. Halsey was appointed Commander in Chief South Pacific Area in October 1942, and he acknowledged the critically important role of the coastwatchers in ensuring the success of the American landings when he said: "The coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal, and Guadalcanal saved the South Pacific". Reference Feldt at p. 285.

American defeat in Battle of Savo Island fails to dislodge the Marines

The appearance of Japanese torpedo-equipped bombers on 8 August caused Vice Admiral Fletcher to revise his agreement to provide carrier support to the Amphibious Force until 10 August. After notifying the Commander in Chief South Pacific Area, Vice Admiral Ghormley, and Rear Admiral Turner of his intention to do so at 1807 hrs on 8 August, Fletcher withdrew his carriers further south of Guadalcanal thirty minutes later. Unknown to Fletcher a Japanese cruiser squadron was closing on Guadalcanal as his ships withdrew.

Commander of the 8th Fleet, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, responded to the radio distress calls from Tulagi by assembling a cruiser squadron to launch a surprise night attack on the American naval and amphibious forces off Guadalcanal. Avoiding detection of the strength of his squadron by Allied reconnaissance aircraft, Mikawa's cruisers were not detected by radar-equipped destroyers as they steered to the south of Savo Island. Employing well-honed night fighting skills, Mikawa targeted the Allied screening cruisers with searchlights at 0130 on 9 August, and using torpedoes and gunfire, inflicted fatal damage on three American cruisers and the Australian cruiser HMAS Canberra. Content with his extraordinary victory, Mikawa failed to press on and attack the almost defenceless transports that were still loaded with the marines’ heavy equipment, weapons and ammunition. Had he attacked the vulnerable transports, the whole American Guadalcanal operation would have been placed in grave jeopardy.

Withdrawal of US Navy support leaves the marines stranded on Guadalcanal and Tulagi

Having lost most of his Screening Group cruisers, Rear Admiral Turner felt obliged to withdraw his Amphibious Force from Guadalcanal on the afternoon of 9 August. The withdrawal of all naval support left the marines stranded on Guadalcanal and Tulagi with limited equipment and supplies of rations and ammunition. The Japanese bombed and strafed the marines by day and shelled them from the sea at night. To defend themselves, the marines had to complete the airfield to take US Marine fighters and bombers. Fortunately, the Japanese had left their construction equipment when they fled. The airfield was completed on 12 August and named Henderson Field after Major Lofton Henderson who lost his life in the Battle of Midway and was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross. On 20 August, Marine Air Group 23, comprising two fighter and two dive-bombers squadrons landed on Henderson Field, and the Cactus Air Force was born.

The Cactus Air Force would prove decisive in maintaining the US Marine hold on Henderson Field and Guadalcanal. Throughout the Guadalcanal Campaign, American air power dominated the daylight hours over Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The Japanese Navy dominated the night hours.

Naval warfare off Guadalcanal

The Battle of Savo Island was the first of seven major naval actions during the Guadalcanal Campaign. In the Pacific War, the aircraft carrier replaced the battleship as the decisive weapon in naval warfare. The Americans initiated Watchtower with four fleet carriers. The Japanese entered the Guadalcanal Campaign with four fleet carriers and two light carriers. When the naval warfare off Guadalcanal ended, the only functioning American carrier in the South Pacific was USS Enterprise (CV-5). The Japanese lost only one light carrier sunk. Despite ending the campaign with more functioning carriers than the Americans, the Japanese were unable to press home this advantage because they had lost too many aircraft and experienced pilots in the Guadalcanal fighting.

Japanese Army response to the Guadalcanal landings

By 10 August, Imperial General Headquarters was satisfied from the number of warships and transports off Guadalcanal and Tulagi that a full US Marine division had landed, but aerial and naval reconnaissance on 11 and 12 August disclosed only a few small boats between Lunga Point and Tulagi. The Japanese concluded erroneously that withdrawal of warships and transports signified that most of the marines had also been withdrawn after raiding Tulagi and Guadalcanal. There was nothing to suggest to Imperial General Headquarters at this stage that Japan was facing a major counter-offensive on Guadalcanal, and the stranded marines would be the beneficiaries of the initial muted Japanese Army response.

The capture of Port Moresby was still deemed to be Japan's highest priority in the South Pacific, and although the bulk of the Nankai Shitai and the 41st Regiment were still at Rabaul awaiting deployment to Buna, and then from Buna to the Kokoda Track, there was no thought of diverting these veteran combat troops to oust the marines from Guadalcanal. Instead, Lieutenant General Hyakutake's 17th Army was ordered to retake Tulagi and Guadalcanal with detachments that would be supplied to 17th Army for that purpose. Army General Staff decided that the 2000-man Ichiki Detachment would be sufficient to clear any remaining marines from Guadalcanal and Tulagi. Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki landed on the northern coast of Guadalcanal on 19 August with his First Echelon comprising 900 men. They launched an immediate frontal attack on the marines at Lunga Point and were effectively annihilated at the Ilu River. Colonel Ichiki committed suicide.

Defeat of Kawaguchi Brigade compels downgrading of Port Moresby priority

Still unaware of the size of the marine force on Guadalcanal, 17th Army next committed Major General Kiyoyaki Kawaguchi's 6,200-man 35th Infantry Brigade to expel the marines from Henderson Field. In the Battle of Bloody Ridge on the night of 13-14 August, Kawaguchi's brigade was routed with very heavy casualties. Many of the survivors died from wounds, starvation, or disease as they battled dense jungle and rugged terrain to reach the Japanese enclave on the north-western corner of the island.

The Kawaguchi Force disaster on Guadalcanal had serious implications for Major General Horii who was fighting his way along the Kokoda Track to Port Moresby. Lieutenant General Hyakutake's 17th Army was conducting major operations simultaneously in Papua and Guadalcanal but lacked the troops and means to reinforce and sustain the two operations at the same time. With Horii in sight of searchlights probing the night sky over Port Moresby, a bitter decision had to be made. Imperial General Headquarters now realised that the Japanese were facing a major Allied counter-offensive on Guadalcanal, with a strategically vital airfield at stake, and switched priorities from Port Moresby to Guadalcanal. Horii was ordered to withdraw his troops from the Kokoda Track to the fortified beachheads and await another opportunity to capture Port Moresby after the marines had been expelled from Guadalcanal and Tulagi.[45] It would now become a battle of attrition on Guadalcanal, with victory likely to go to the side that could reinforce the fastest.[46]

By mid-October 1942, the Japanese had concentrated some 20,000 troops on Guadalcanal. The next Japanese move against Henderson Field involved Major General Masai Maruyama's 2nd Division. Maruyama's troops battled dense jungle and heavy rain to reach the marine lines on the night of 23-24 October. After two nights of fierce fighting, the Japanese losses were so heavy that Maruyama abandoned the attack and led the survivors back to the Japanese enclave.

Logistics defeat the Japanese on Guadalcanal

The Japanese moved reinforcements and supplies the 909 km (565 miles) from Rabaul to Guadalcanal at night by cruisers and destroyers. After delivering troops and cargo, the warships would shell Henderson Field before they departed. A major problem for the Japanese was the limited cargo capacity of warships and it was never possible to supply their troops on Guadalcanal with adequate rations and equipment. Slow moving transports were too vulnerable to attack by Allied aircraft, and by January 1943, the 20,000 Japanese troops on Guadalcanal were close to starvation. Under the cover of the Cactus Air Force and B-17s flying from New Hebrides and New Caledonia, and protected by the US Navy, the Americans could regularly bring in thousands of reinforcements and supplies during daylight hours for the depleted and exhausted 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal.

Appreciating that Japan faced inevitable defeat in the southern Solomons, Imperial General Headquarters ordered the evacuation of all Japanese troops on Guadalcanal. By 7 February 1943, the last of some 13,000 starving and disease ridden Japanese survivors had been withdrawn from Guadalcanal by sea. The Guadalcanal Campaign had ended, and with it, the threat of a Japanese blockade that had been intended to produce Australia's submission to Japan.

Modern concept of a Battle for Australia

The modern concept of a Battle for Australia owes its origin to a private letter dated 24 July 1997 that Pacific War historian James Kenneth Bowen wrote to the National President of the Returned & Services League of Australia (RSL), Major General W. B. Digger James, AC, MBE, MC. Mr Bowen was then Honorary Counsel and State Executive member of the Victorian RSL.[citation needed] At private meetings during 1997, Mr Bowen and Major General James defined the concept of a Battle for Australia to describe the clash of Japanese and American strategic war aims that produced a series of great battles in 1942 across the northern approaches to Australia, including the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Kokoda Campaign, and Guadalcanal Campaign. In this context, the Battle for Australia was to be viewed as a lengthy and bloody struggle to prevent the Japanese achieving their strategic Pacific War aims of controlling Australia, and preventing the United States aiding Australia and using Australia as a base for launching a counter-offensive against the Japanese military advance. For their part, the Americans were determined to protect their access to Australia and its New Guinea territories in 1942, even at the risk of their precious fleet carriers that had survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. This modern concept saw the Battle for Australia beginning on 11 March 1942 when Japan's Imperial General Headquarters- Government Liaison Conference approved implementation of Operation FS, with a view to producing Australia's submission to Japan by isolation from American aid, intensified blockade, and psychological warfare.[47] For practical purposes, the Battle for Australia was seen as concluding when the Japanese were ousted from Papua on 22 January 1943 and Guadalcanal on 7 February 1943.[citation needed]

Historiography and commemoration

In a 2006 speech, the principal historian at the Australian War Memorial, Dr. Peter Stanley, argued that the concept of a Battle for Australia is invalid as the events which are considered to form the battle were only loosely related. Stanley argued that "The Battle for Australia movement arises directly out of a desire to find meaning in the terrible losses of 1942"; and "there was no 'Battle for Australia', as such", as the Japanese did not launch a co-ordinated campaign directed against Australia. Furthermore, Stanley stated that the phrase 'Battle for Australia' was not used until the 1990s and this 'battle' of World War II is not recognised by countries other than Australia.

In 2008 the Australian Government proclaimed that commemorations for the Battle for Australia would be held annually on the first Wednesday in September, with the day being designated 'Battle for Australia Day'.[48]

Major battles

- Japanese air raids, including:

- the bombing of Darwin and

- the attack on Broome

- Battle of the Coral Sea

- Japanese submarine attacks, including:

- the New Guinea campaign, including the

See also

Notes

- ^ Stanley, Peter. "What 'Battle for Australia'?". The Drum. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Horner (1993), pp. 2–3

- ^ Bullard (2007), p.69

- ^ Frei (1991), pp. 162–171

- ^ Frei (1991), p. 171

- ^ Frei (1991), pp. 171–172

- ^ Costello, pp. 175-181