Endianness: Difference between revisions

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

</pre> |

</pre> |

||

Life example on a Big-endian [[SPARC]] machine. The printout is |

Life example on a Big-endian [[SPARC]] machine. The printout is done with addresses (coordinate system) growing to right [ 0 1 2 3 ... ]: |

||

<source lang="cpp"> |

<source lang="cpp"> |

||

Revision as of 20:04, 10 June 2011

In computing, the term endian or endianness refers to the ordering of individually addressable sub-components within a longer data item as stored in external memory (or, sometimes, as sent on a serial connection). These sub-components are typically 16- or 32-bit words, 8-bit bytes, or even bits. Endianness is a difference in data representation at the hardware level and may be transparent (or not) at higher levels depending on factors such as the type of high level language used.

The most common cases refer to how bytes are ordered within a single 16-, 32-, or 64-bit word, and endianness is then the same as byte order.[1] The usual contrast is whether the most-significant or least-significant byte is ordered first — i.e. at the lowest byte address — within the larger data item. A big-endian machine stores the most-significant byte first (at the lowest address), and a little-endian machine stores the least-significant byte first. In these standard forms, the bytes remain ordered by significance. However, mixed forms are also possible where the ordering of bytes within a 16-bit word may differ from the ordering of 16-bit words within a 32-bit word, for instance. Although rare, such cases do exist and may sometimes be referred to as mixed-endian or middle-endian.

Endianness is important as a low-level attribute of a particular data format. For example, the order in which the two bytes of an UCS-2 character are stored in memory is of considerable importance in network programming where two computers with different byte orders may be communicating with each other. Failure to account for a varying endianness across architectures when writing code for mixed platforms leads to failures and bugs that can be difficult to detect.

| Endian | First Byte (lowest address) |

Middle Bytes | Last Byte (highest address) |

Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| big | most significant | ... | least significant | Similar to a number written on paper (in English) |

| little | least significant | ... | most significant | Arithmetic calculation order (see carry propagation) |

Endianness and hardware

The full register width among different CPUs and other processor types varies widely (typically between 4 and 64 bits). The internal bit-, byte-, or word-ordering within such a register is normally not considered "endianness", despite the fact that some CPU instructions may address individual bits (or other parts) using various kinds of internal addressing schemes. The "endianness" only describes how the bits are organized as seen from the outside (i.e. when stored in memory). The fact that some assembly languages label bits in an unorthodox manner is also largely another matter (a few architectures/assemblers turn the conventional msb..lsb = D31..D0 the other way round, so that msb=D0).

Large integers are usually stored in memory as a sequence of smaller ones and obtained by simple concatenation. The simple forms are:

- increasing numeric significance with increasing memory addresses (or increasing time), known as little-endian, and

- decreasing numeric significance with increasing memory addresses (or increasing time), known as big-endian [2]

Well-known processor architectures that use the little-endian format include x86 (including x86-64), 6502 (including 65802, 65C816), Z80 (including Z180, eZ80 etc.), MCS-48, 8051, DEC Alpha, Altera Nios, Atmel AVR, SuperH, VAX, and, largely, PDP-11. Well-known processors that use the big-endian format include Motorola 6800 and 68k, IBM POWER, and System/360 and its successors such as System/370, ESA/390, and z/Architecture. The PDP-10 also used big-endian addressing for byte-oriented instructions. SPARC historically used big-endian until version 9, which is bi-endian just like the ARM architecture, and the PowerPC and Power Architecture descendants of IBM POWER are also bi-endian (see below).

Serial protocols may also be regarded as either little or big-endian at the bit- and/or byte-levels (which may differ). Many serial interfaces, such as the ubiquitous USB, are little-endian at the bit-level. Physical standards like RS-232, RS-422 and RS-485 are also typically used with UARTs that send the least significant bit first, such as in industrial instrumentation applications, lighting protocols (DMX512), and so on. The same could be said for digital current loop signaling systems such as MIDI. There are also several serial formats where the most significant bit is normally sent first, such as I²C and the related SMBus. However, the bit order may often be reversed (or is "transparent") in the interface between the UART or communication controller and the host CPU or DMA controller (and/or system memory), especially in more complex systems and personal computers. These interfaces may be of any type and are often configurable.

Bi-endian hardware

Some architectures (including ARM, PowerPC, Alpha, SPARC V9, MIPS, PA-RISC and IA-64) feature a setting which allows for switchable endianness in data segments, code segments or both. This feature can improve performance or simplify the logic of networking devices and software. The word bi-endian, when said of hardware, denotes the capability of the machine to compute or pass data in either endian format.

Many of these architectures can be switched via software to default to a specific endian format (usually done when the computer starts up); however, on some systems the default endianness is selected by hardware on the motherboard and cannot be changed via software (e.g., the Alpha, which runs only in big-endian mode on the Cray T3E).

Note that the term "bi-endian" refers primarily to how a processor treats data accesses. Instruction accesses (fetches of instruction words) on a given processor may still assume a fixed endianness, even if data accesses are fully bi-endian, though this is not always the case, such as on Intel's IA-64-based Itanium CPU, which allows both.

Note, too, that some nominally bi-endian CPUs require motherboard help to fully switch endianness. For instance, the 32-bit desktop-oriented PowerPC processors in little-endian mode act as little-endian from the point of view of the executing programs but they require the motherboard to perform a 64-bit swap across all 8 byte lanes to ensure that the little-endian view of things will apply to I/O devices. In the absence of this unusual motherboard hardware, device driver software must write to different addresses to undo the incomplete transformation and also must perform a normal byte swap.

Some CPUs, such as many PowerPC processors intended for embedded use, allow per-page choice of endianness.

Floating-point and endianness

Although the ubiquitous x86 of today use little-endian storage for all types of data (integer, floating point, BCD), there have been a few historical machines where floating point numbers were represented in big-endian form while integers were represented in little-endian form.[3] Because there have been many floating point formats with no "network" standard representation for them, there is no formal standard for transferring floating point values between heterogeneous systems. It may therefore appear strange that the widespread IEEE 754 floating point standard does not specify endianness.[4] Theoretically, this means that not even standard IEEE floating point data written by one machine may be readable by another. However, on modern standard computers (i.e. implementing IEEE 754), one may in practice safely assume that the endianness is the same for floating point numbers as for integers, making the conversion straight forward regardless of data type. (Small embedded systems using special floating point formats may be another matter however.)

Endianness and operating systems on architectures

Little-endian operating systems:

- Linux on x86, x86-64, MIPSEL, Alpha, Itanium, S+core, MN103, CRIS, Blackfin, MicroblazeEL, ARM, M32REL, TILE, SH, XtensaEL and UniCore32

- Mac OS X on x86, x86-64

- OpenVMS on VAX, Alpha and Itanium

- Solaris on x86, x86-64, PowerPC

- Tru64 UNIX on Alpha

- Windows on x86, x86-64, Alpha, PowerPC, MIPS and Itanium

Big-endian operating systems:

- AIX on POWER

- AmigaOS on PowerPC and 680x0

- HP-UX on Itanium and PA-RISC

- Linux on MIPS, SPARC, PA-RISC, POWER, PowerPC, 680x0, ESA/390, z/Architecture, H8, FR-V, AVR32, Microblaze, ARMEB, M32R, SHEB and Xtensa.

- Mac OS on PowerPC and 680x0

- Mac OS X on PowerPC

- MVS and DOS/VSE on ESA/390, and z/VSE and z/OS on z/Architecture

- Solaris on SPARC

Etymology

The term big-endian originally comes from Jonathan Swift's satirical novel Gulliver’s Travels by way of Danny Cohen in 1980.[5] In 1726, Swift described tensions in Lilliput and Blefuscu: whereas royal edict in Lilliput requires cracking open one's soft-boiled egg at the small end, inhabitants of the rival kingdom of Blefuscu crack theirs at the big end (giving them the moniker Big-endians).[6] The terms little-endian and endianness have a similar intent.[7]

"On Holy Wars and a Plea for Peace"[5] by Danny Cohen ends with: "Swift's point is that the difference between breaking the egg at the little-end and breaking it at the big-end is trivial. Therefore, he suggests, that everyone does it in his own preferred way. We agree that the difference between sending eggs with the little- or the big-end first is trivial, but we insist that everyone must do it in the same way, to avoid anarchy. Since the difference is trivial we may choose either way, but a decision must be made."

History

The problem of dealing with data in different representations is sometimes termed the NUXI problem.[8] This terminology alludes to the issue that a value represented by the byte-string "UNIX" on a big-endian system may be stored as "NUXI" on a PDP-11 middle-endian system; UNIX was one of the first systems to allow the same code to run on, and transfer data between, platforms with different internal representations.

An often-cited argument in favor of big-endian is that it is consistent with the ordering commonly used in natural languages.[9] Spoken languages have a wide variety of organizations of numbers: the decimal number 92 is/was spoken in English as ninety-two, in German and Dutch as two and ninety and in French as four-twenty-twelve with a similar system in Danish (two-and-four-and-a-half-times-twenty). However, numbers are written almost universally in the Hindu-Arabic numeral system, in which the most significant digits are written first in languages written left-to-right, and last in languages written right-to-left.[dubious – discuss]

Optimization

The little-endian system has the property that the same value can be read from memory at different lengths without using different addresses (even when alignment restrictions are imposed). For example, a 32-bit memory location with content 4A 00 00 00 can be read at the same address as either 8-bit (value = 4A), 16-bit (004A), 24-bit (00004A), or 32-bit (0000004A), all of which retain the same numeric value. Although this little-endian property is rarely used directly by high-level programmers, it is often employed by code optimizers as well as by assembly language programmers.

On the other hand, in some situations it may be useful to obtain an approximation of a multi-byte or multi-word value by reading only its most-significant portion instead of the complete representation; a big-endian processor may read such an approximation using the same base-address that would be used for the full value.

Calculation order

Little-endian representation simplifies hardware in processors that add multi-byte integral values a byte at a time, such as small-scale byte-addressable processors and microcontrollers. As carry propagation must start at the least significant bit (and thus byte), multi-byte addition can then be carried out with a monotonic incrementing address sequence, a simple operation already present in hardware. On a big-endian processor, its addressing unit has to be told how big the addition is going to be so that it can hop forward to the least significant byte, then count back down towards the most significant. However, high performance processors usually perform these operations as a single operation, fetching multi-byte operands from memory in a single operation, so that the complexity of the hardware is not affected by the byte ordering.

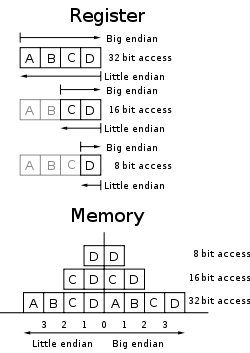

Diagram for mapping registers to memory locations

Using this chart, one can map an access (or, for a concrete example: "write 32 bit value to address 0") from register to memory or from memory to register. To help in understanding that access, little and big endianness can be seen in the diagram as differing in their coordinate system's orientation. Big endianness's atomic units (in this example the atomic unit is the byte) and memory coordinate system increases in the diagram from left to right, while little endianness's units increase from right to left.

A Simple reminder is "In Little Endian, The Least significant byte goes into the Lowest value slot". So in the above example, D, the least significant byte, goes into slot 0.

Life example on a Little-endian x86 machine. The printout is done with done with addresses (coordinate system) growing to left [ ... 3 2 1 0 ]:

#include <stdio.h>

/* x86 */

main () {

unsigned int ra = 0x0a0b0c0d;

unsigned char *rp = (char *)&ra;

unsigned int wa = 0x0a0b0c0d, wd = 0;

unsigned char *wp = (char *)&wd;

printf("(Memory address growing left) 3 2 1 0 \n");

/* x86: store 8 bits of <wa(0x0a0b0c[0d])> at address <wp(=&wd)> */

__asm__ __volatile__("movb %1,(%0)\n\t" : : "a" ((unsigned char *)wp), "r" ((unsigned char)wa) );

/* x86: show with coordinates growing to left: ... 3 2 1 0|*/

printf("register(0x0a0b0c[0d])->memory 8 bit: %02x\n", wp[0]);

/* x86: store 16 bits of <wa(0x0a0[b0c0d])> at address <wp(=&wd)> */

__asm__ __volatile__("movw %1,(%0)\n\t" : : "a" ((unsigned short *)wp), "r" ((unsigned short)wa) );

/* x86: show with coordinates growing to left: ... 3 2 1 0|*/

printf("register(0x0a0b[0c0d])->memory 16 bit: %02x %02x\n", wp[1], wp[0]);

/* x86: store 32 bits of <wa(0x[0a0b0c0d])> at address <wp(=&wd)> */

__asm__ __volatile__("movl %1,(%0)\n\t" : : "a" ((unsigned int *)wp), "r" ((unsigned int)wa) );

/* x86: show with coordinates growing to left: ... 3 2 1 0| */

printf("register(0x[0a0b0c0d])->memory 32 bit: %02x %02x %02x %02x\n", wp[3], wp[2], wp[1], wp[0]);

printf(" 3 2 1 0 (Memory address growing left)\n");

printf("memory( 0a 0b 0c[0d])->register 8 bit: %02x\n", rp[0]);

printf("memory( 0a 0b[0c 0d])->register 16 bit: %04x\n", *(unsigned short *)rp);

printf("memory([0a 0b 0c 0d])->register 32 bit: %08x\n", *(unsigned int *)rp);

}

The output of the program started on a x86 machine is:

(Memory address growing left) 3 2 1 0

register(0x0a0b0c[0d])->memory 8 bit: 0d

register(0x0a0b[0c0d])->memory 16 bit: 0c 0d

register(0x[0a0b0c0d])->memory 32 bit: 0a 0b 0c 0d

3 2 1 0 (Memory address growing left)

memory( 0a 0b 0c[0d])->register 8 bit: 0d

memory( 0a 0b[0c 0d])->register 16 bit: 0c0d

memory([0a 0b 0c 0d])->register 32 bit: 0a0b0c0d

Life example on a Big-endian SPARC machine. The printout is done with addresses (coordinate system) growing to right [ 0 1 2 3 ... ]:

/* sparc */

main () {

unsigned int ra = 0x0a0b0c0d;

unsigned char *rp = (char *)&ra;

unsigned int wa = 0x0a0b0c0d, wd;

unsigned char *wp = (char *)&wd;

printf("(Memory address growing right) 0 1 2 3 \n");

/* sparc: store 8 bits of <wa(0x0a0b0c[0d])> at address <wp(=&wd)> */

__asm__ __volatile__("stub %1,[%0]\n\t" : : "r" (wp), "r" (wa) );

/* sparc: show with coordinates growing to right: | 0 1 2 3 ... */

printf("register(0x0a0b0c[0d])->memory 8 bit: %02x\n", wp[0]);

/* sparc: store 16 bits of <wa(0x0a0b[0c0d])> at address <wp(=&wd)> */

__asm__ __volatile__("sth %1,[%0]\n\t" : : "r" (wp), "r" (wa) );

/* sparc: show with coordinates growing to right: | 0 1 2 3 ... */

printf("register(0x0a0b[0c0d])->memory 16 bit: %02x %02x\n", wp[0], wp[1]);

/* sparc: store 32 bits of <wa(0x[0a0b0c0d])> at address <wp(=&wd)> */

__asm__ __volatile__("st %1,[%0]\n\t" : : "r" (wp), "r" (wa) );

/* sparc: show with coordinates growing to right: | 0 1 2 3 ... */

printf("register(0x[0a0b0c0d])->memory 32 bit: %02x %02x %02x %02x\n", wp[0], wp[1], wp[2], wp[3]);

printf(" 0 1 2 3 (Memory address growing right)\n");

printf("memory([0a]0b 0c 0d )->register 8 bit: %02x\n", rp[0]);

printf("memory([0a 0b]0c 0d )->register 16 bit: %04x\n", *(unsigned short *)rp);

printf("memory([0a 0b 0c 0d])->register 32 bit: %08x\n", *(unsigned int *)rp);

}

The output of the program started on a SPARC machine is:

(Memory address growing right) 0 1 2 3

register(0x0a0b0c[0d])->memory 8 bit: 0d

register(0x0a0b[0c0d])->memory 16 bit: 0c 0d

register(0x[0a0b0c0d])->memory 32 bit: 0a 0b 0c 0d

0 1 2 3 (Memory address growing right)

memory([0a]0b 0c 0d )->register 8 bit: 0a

memory([0a 0b]0c 0d )->register 16 bit: 0a0b

memory([0a 0b 0c 0d])->register 32 bit: 0a0b0c0d

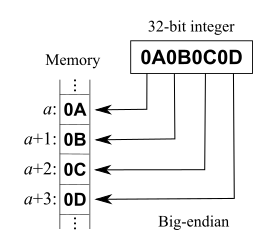

Examples of storing the value 0A0B0C0Dh in memory

- Note that hexadecimal notation is used.

To illustrate the notions this section provides example layouts of the 32-bit number 0A0B0C0Dh in the most common variants of endianness. There exists several digital processors that use other formats, but these two are the most common in general processors. That is true for typical embedded systems as well as for general computer CPU(s). Most processors used in non CPU roles in typical computers (in storage units, peripherals etc.) also use one of these two basic formats, although not always 32-bit of course.

All the examples refer to the storage in memory of the value.

Big-endian

Atomic element size 8-bit, address increment 1-byte (octet)

| increasing addresses → | |||||

| 0Ah | 0Bh | 0Ch | 0Dh | ||

The most significant byte (MSB) value, which is 0Ah in our example, is stored at the memory location with the lowest address, the next byte value in significance, 0Bh, is stored at the following memory location and so on. This is akin to Left-to-Right reading in hexadecimal order.

Atomic element size 16-bit

| increasing addresses → | |||||

| 0A0Bh | 0C0Dh | ||||

The most significant atomic element stores now the value 0A0Bh, followed by 0C0Dh.

Little-endian

Atomic element size 8-bit, address increment 1-byte (octet)

| increasing addresses → | |||||

| 0Dh | 0Ch | 0Bh | 0Ah | ||

The least significant byte (LSB) value, 0Dh, is at the lowest address. The other bytes follow in increasing order of significance.

Atomic element size 16-bit

| increasing addresses → | |||||

| 0C0Dh | 0A0Bh | ||||

The least significant 16-bit unit stores the value 0C0Dh, immediately followed by 0A0Bh. Note that 0C0Dh and 0A0Bh represent integers, not bit layouts (see bit numbering).

Byte addresses increasing from right to left

Visualising memory addresses from left to right makes little-endian values appear backwards. If the addresses are written increasing towards the left instead, each individual little-endian value will appear forwards. However strings of values or characters appear reversed instead.

With 8-bit atomic elements:

| ← increasing addresses | |||||

| 0Ah | 0Bh | 0Ch | 0Dh | ||

The least significant byte (LSB) value, 0Dh, is at the lowest address. The other bytes follow in increasing order of significance.

With 16-bit atomic elements:

| ← increasing addresses | |||||

| 0A0Bh | 0C0Dh | ||||

The least significant 16-bit unit stores the value 0C0Dh, immediately followed by 0A0Bh.

The display of text is reversed from the normal display of languages such as English that read from left to right. For example, the word "XRAY" displayed in this manner, with each character stored in an 8-bit atomic element:

| ← increasing addresses | |||||

| "Y" | "A" | "R" | "X" | ||

If pairs of characters are stored in 16-bit atomic elements (using 8 bits per character), it could look even stranger:

| ← increasing addresses | |||

| "AY" | "XR" | ||

This conflict between the memory arrangements of binary data and text is intrinsic to the nature of the little-endian convention, but is a conflict only for languages written left-to-right, such as Indo-European languages including English. For right-to-left languages such as Arabic and Hebrew, there is no conflict of text with binary, and the preferred display in both cases would be with addresses increasing to the left. (On the other hand, right-to-left languages have a complementary intrinsic conflict in the big-endian system.)

Middle-endian

Numerous other orderings, generically called middle-endian or mixed-endian, are possible. On the PDP-11 (16-bit little-endian) for example, the compiler stored 32-bit values with the 16-bit halves swapped from the expected little-endian order. This ordering is known as PDP-endian.

- storage of a 32-bit word on a PDP-11

| increasing addresses → | |||||

| 0Bh | 0Ah | 0Dh | 0Ch | ||

The ARM architecture can also produce this format when writing a 32-bit word to an address 2 bytes from a 32-bit word alignment.

Endianness in networking

Many network protocols may be regarded as big-endian in the sense that the most significant byte is sent first.

The telephone network, historically and presently, sends the most significant part first, the area code; doing so allows routing while a telephone number is being composed.

The Internet Protocol defines big-endian as the standard network byte order used for all numeric values in the packet headers and by many higher level protocols and file formats that are designed for use over IP. The Berkeley sockets API defines a set of functions to convert 16-bit and 32-bit integers to and from network byte order: the htonl (host-to-network-long) and htons (host-to-network-short) functions convert 32-bit and 16-bit values respectively from machine (host) to network order; the ntohl and ntohs functions convert from network to host order. These functions may do nothing on a big-endian system.

In CANopen multi-byte parameters are always sent least significant byte first (little endian).

While the lowest network protocols may deal with sub-byte formatting, all the layers above them usually consider the byte (mostly meant as octet) as their atomic unit.

Endianness in files and byte swap

Endianness is a problem when a binary file created on a computer is read on another computer with different endianness. Some compilers have built-in facilities to deal with data written in other formats. For example, the Intel Fortran compiler supports the non-standard CONVERT specifier, so a file can be opened as

OPEN(unit,CONVERT='BIG_ENDIAN',...)

or

OPEN(unit,CONVERT='LITTLE_ENDIAN',...)

If the compiler does not support such conversion, the programmer needs to swap the bytes by an ad hoc code.

Fortran sequential unformatted files created with one endianness usually cannot be read on a system using the other endianness because Fortran usually implements a record (defined as the data written by a single Fortran statement) as data preceded and succeeded by count fields, which are integers equal to the number of bytes in the data. An attempt to read such file on a system of the other endianness then results in a run-time error, because the count fields are incorrect.

Application binary data formats, such as for example MATLAB .mat files, or the .BIL data format, used in topography, are usually endianness-independent. This is achieved by storing the data always in one fixed endianness, or carrying with the data a switch to indicate which endianness the data was written with. When reading the file, the application converts the endianness, transparently to the user.

This is the case of TIFF image files, which instructs in its header about endianness of their internal binary integers. If a file starts with the signature "MM" it means that integers are represented as big-endian while "II" means little-endian. Those signatures need a single 16 bit word each, and they are palindromes (that is, they read the same forwards and backwards), so they are endianness independent. "I" stands for Intel and "M" stands for Motorola, the respective CPU providers of the IBM PC compatibles and Apple Macintosh platforms in the 1980s. Intel CPUs are little-endian, while Motorola 680x0 CPUs are big-endian. This explicit signature allows a TIFF reader program to swap bytes if necessary when a given file was generated by a TIFF writer program running on a computer with a different endianness.

The LabVIEW programming environment, though most commonly installed on Windows machines, was first developed on a Macintosh, and uses Big Endian format for its binary numbers, while most Windows programs use Little Endian format. [10]

Note that since the required byte swap depends on the length of the variables stored in the file (two 2 byte integers require a different swap than one 4 byte integer), a general utility to convert endianness in binary files cannot exist.

"Bit endianness"

The terms bit endianness or bit-level endianness are seldom used when talking about the representation of a stored value, as they are only meaningful for the rare computer architectures where each individual bit has a unique address. They are used however to refer to the transmission order of bits over a serial medium. Most often that order is transparently managed by the hardware and is the bit-level analogue of little-endian (low-bit first), although protocols exist which require the opposite ordering (e.g. I²C). In networking, the decision about the order of transmission of bits is made in the very bottom of the data link layer of the OSI model.

Other meanings

Some authors extend the usage of the word "endianness", and of related terms, to entities such as street addresses, date formats and others. Such usages—basically reducing endianness to a mere synonym of ordering of the parts—are non-standard usage[citation needed] (e.g., ISO 8601:2004 talks about "descending order year-month-day", not about "big-endian format"), do not have widespread usage, and are generally (other than for date formats) employed in a metaphorical sense.

"Endianness" is sometimes used to describe the order of the components of a domain name, e.g. 'en.wikipedia.org' (the usual modern 'little-endian' form) versus the reverse-DNS 'org.wikipedia.en' ('big-endian', used for naming components, packages, or types in computer systems, for example Java packages, Macintosh ".plist" files, etc.). URLs could be considered 'middle-endian', as they start in the usual modern 'little-endian' form, but after the TLD, a 'big-endian' format is used to point to a specific file or folder.

References and notes

- ^ For hardware, the Jargon File also reports the less common expression byte sex [1]. It is unclear whether this terminology is also used when more than two orderings are possible. Similarly, the manual for the ORCA/M assembler refers to a field indicating the order of the bytes in a number field as

NUMSEX, and the Mac OS X operating system refers to "byte sex" in its compiler tools [2]. - ^ Note that, in these expressions, the term "end" is meant as "extremity", not as "last part"; and that big and little say which extremity is written first.

- ^ "Floating point formats".

- ^ "pack - convert a list into a binary representation".

- ^ a b Danny Cohen (1980-04-01). On Holy Wars and a Plea for Peace. IEN 137.

...which bit should travel first, the bit from the little end of the word, or the bit from the big end of the word? The followers of the former approach are called the Little-Endians, and the followers of the latter are called the Big-Endians.

Also published at IEEE Computer, October 1981 issue. - ^ Jonathan Swift (1726). Gulliver's Travels.

Which two mighty powers have, as I was going to tell you, been engaged in a most obstinate war for six-and-thirty moons past. (...) the primitive way of breaking eggs, before we eat them, was upon the larger end; (...) the emperor his father published an edict, commanding all his subjects, upon great penalties, to break the smaller end of their eggs. (...) Many hundred large volumes have been published upon this controversy: but the books of the Big-endians have been long forbidden (...)

- ^ David Cary. "Endian FAQ". Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "NUXI problem". The Jargon File. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ^ Cf. entries 539 and 704 of the Linguistic Universals Database

- ^ read write binary files with LabVIEW

Further reading

- Danny Cohen (1980-04-01). On Holy Wars and a Plea for Peace. IEN 137. Also published at IEEE Computer, October 1981 issue.

- David V. James (1990). "Multiplexed buses: the endian wars continue". IEEE Micro. 10 (3): 9–21. doi:10.1109/40.56322. ISSN 0272-1732. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Bertrand Blanc, Bob Maaraoui (December 2005). "Endianness or Where is Byte 0?" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-12-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

- Understanding big and little endian byte order

- The Layout of Data in Memory

- Byte Ordering PPC

- Writing endian-independent code in C

- How to convert an integer to little endian or big endian

- C-Level Code Illustration

- xlong/xshort data-types, the Big-Endian, Little-Endian Rosetta stone

This article is based on material taken from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing prior to 1 November 2008 and incorporated under the "relicensing" terms of the GFDL, version 1.3 or later.