Science and the Catholic Church: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Undid revision 445695790 by Proyectocambio (talk) Tag: section blanking |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

On the other hand, the [[conflict thesis]] proposes an intrinsic intellectual conflict between the Church and [[science]]. The original historical usage of the term denoted that the historical record indicates the Church’s perpetual opposition to science. Later uses of the term denote the Church's [[epistemology|epistemological]] opposition to science. The conflict thesis interprets the relationship between the Church and science as inevitably leading to public hostility, when religion aggressively challenges new scientific ideas — as in the [[Galileo affair|Galileo Affair]] (1614–15). |

On the other hand, the [[conflict thesis]] proposes an intrinsic intellectual conflict between the Church and [[science]]. The original historical usage of the term denoted that the historical record indicates the Church’s perpetual opposition to science. Later uses of the term denote the Church's [[epistemology|epistemological]] opposition to science. The conflict thesis interprets the relationship between the Church and science as inevitably leading to public hostility, when religion aggressively challenges new scientific ideas — as in the [[Galileo affair|Galileo Affair]] (1614–15). |

||

==scientific method == |

|||

Long life to science, death to dogmas, and peace and love. Make love. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 18:50, 19 August 2011

The relationship between the Roman Catholic Church and science has historically varied between a onesided support from the Church to clashes of accusations of heresy and back to a reserved supporting stance from the Church. On the other hand, religion has lost its status of universal truth in the more and more independent scientific community resisting interference from the Church. While science matters were originally deeply interconnected with theological matters, the scientific community of today and society in general consider science and religion to be fully independent.

Originally most research took place in Roman Catholic universities that were staffed by members of religious orders who had the education and means to conduct scientific investigation.[1] Catholic universities, scholars and many priests including Nicolaus Copernicus, Roger Bacon, Albertus Magnus, Robert Grosseteste, Nicholas Steno, Francesco Grimaldi, Giambattista Riccioli, Roger Boscovich, Athanasius Kircher, Gregor Mendel, Georges Lemaître and many others, were responsible for many important scientific discoveries. Since the late 16th century the Jesuits have produced the large majority of priest-scientists, who contributed to worldwide cultural exchange by spreading their developments in knowledge to Asia, Africa, and the Americas.[1][2]

On the other hand, the conflict thesis proposes an intrinsic intellectual conflict between the Church and science. The original historical usage of the term denoted that the historical record indicates the Church’s perpetual opposition to science. Later uses of the term denote the Church's epistemological opposition to science. The conflict thesis interprets the relationship between the Church and science as inevitably leading to public hostility, when religion aggressively challenges new scientific ideas — as in the Galileo Affair (1614–15).

History

Condemnations of 1210-1277

The Condemnations of 1210-1277 were enacted at the medieval University of Paris to restrict certain teachings as being heretical. These included a number of medieval theological teachings, but most importantly the physical treatises of Aristotle. The investigations of these teachings were conducted by the Bishops of Paris. The Condemnations of 1277 are traditionally linked to an investigation requested by Pope John XXI, although whether he actually supported drawing up a list of condemnations is unclear.

Approximately sixteen lists of censured theses were issued by the University of Paris during the 13th and 14th centuries.[3] Most of these lists of propositions were put together into systematic collections of prohibited articles.[3] Of these, the Condemnations of 1277 are considered particularly important by historians as they allowed scholars to break from the restrictions of Aristotelian science.[4] This had positive effects on the development of science, with some historians going so far as to claim that they represented the beginnings of modern science.[4]

Copernicus

In 1533, Johann Albrecht Widmannstetter delivered a series of lectures in Rome outlining Copernicus' theory. Pope Clement VII and several Catholic cardinals heard the lectures and were interested in the theory. On 1 November 1536, Nikolaus von Schönberg, Archbishop of Capua and since the previous year a cardinal, wrote to Copernicus from Rome:

Some years ago word reached me concerning your proficiency, of which everybody constantly spoke. At that time I began to have a very high regard for you... For I had learned that you had not merely mastered the discoveries of the ancient astronomers uncommonly well but had also formulated a new cosmology. In it you maintain that the earth moves; that the sun occupies the lowest, and thus the central, place in the universe... Therefore with the utmost earnestness I entreat you, most learned sir, unless I inconvenience you, to communicate this discovery of yours to scholars, and at the earliest possible moment to send me your writings on the sphere of the universe together with the tables and whatever else you have that is relevant to this subject ...[5]

By then Copernicus' work was nearing its definitive form, and rumors about his theory had reached educated people all over Europe. Despite urgings from many quarters, Copernicus delayed publication of his book, perhaps from fear of criticism—a fear delicately expressed in the subsequent dedication of his masterpiece to Pope Paul III. Scholars disagree on whether Copernicus' concern was limited to possible astronomical and philosophical objections, or whether he was also concerned about religious objections.[6]

At original publication, Copernicus' epoch-making book caused only mild controversy, and provoked no fierce sermons about contradicting Holy Scripture. It was only three years later, in 1546, that a Dominican, Giovanni Maria Tolosani, denounced the theory in an appendix to a work defending the absolute truth of Scripture.[7] He also noted that the Master of the Sacred Palace (i.e., the Catholic Church's chief censor), Bartolomeo Spina, a friend and fellow Dominican, had planned to condemn De revolutionibus but had been prevented from doing so by his illness and death.[8]

Gessner

Conrad Gessner's great zoological work, Historiae animalium, appeared in 4 vols. (quadrupeds, birds, fishes) folio, 1551-1558, at Zürich, a fifth (snakes) being issued in 1587. This work is recognized as the starting-point of modern zoology. There was extreme religious tension at the time Historiae animalium came out. Gesner was Protestant. Under Pope Paul IV it was felt that the religious convictions of an author contaminated all his writings,[9] so - without any regard for the content of the work - it was added to the Roman Catholic Church's list of prohibited books.[10]

Galileo Galilei

- See also: Galileo affair and Galileo Galilei

The 1633 Church condemnation of Galileo Galilei created a time of antagonism between the Church and science. According to historian Thomas Noble, the effect of the Galileo affair was to restrict scientific development in some European countries.[1] In part because of lessons learned from the Galilei affair, the Church created the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1603. This scientific organization reached its present form by 1936.[11]

Galileo's championing of Copernicanism was controversial within his lifetime, when a large majority of philosophers and astronomers still subscribed (at least outwardly) to the geocentric view that the Earth is at the centre of the universe. It has been much debated why it was not until six decades after Spina and Tolosani's attacks on Copernicus's work that the Catholic Church took any official action against it. Proposed reasons have included the personality of Galileo Galilei and the availability of evidence such as telescope observations[citation needed].

After 1610, when he began publicly supporting the heliocentric view, which placed the Sun at the centre of the universe, Galileo met with bitter opposition from some philosophers and clerics, and two of the latter eventually denounced him to the Roman Inquisition early in 1615. Although he was cleared of any offence at that time, the Catholic Church nevertheless condemned heliocentrism as "false and contrary to Scripture" in February 1616,[12] and Galileo was warned to abandon his support for it—which he promised to do. When he later defended his views in his most famous work, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, published in 1632, he was tried by the Inquisition, found "vehemently suspect of heresy," forced to recant, and spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

In March 1616, the Roman Catholic Church's Congregation of the Index issued a decree suspending De revolutionibus until it could be "corrected," on the grounds that the supposedly Pythagorean doctrine[13] that the Earth moves and the Sun does not was "false and altogether opposed to Holy Scripture."[14] The same decree also prohibited any work that defended the mobility of the Earth or the immobility of the Sun, or that attempted to reconcile these assertions with Scripture.

On the orders of Pope Paul V, Cardinal Robert Bellarmine gave Galileo prior notice that the decree was about to be issued, and warned him that he could not "hold or defend" the Copernican doctrine.[15] The corrections to De revolutionibus, which omitted or altered nine sentences, were issued four years later, in 1620.[16]

In 1633 Galileo was convicted of grave suspicion of heresy for "following the position of Copernicus, which is contrary to the true sense and authority of Holy Scripture,"[17] and was placed under house arrest for the rest of his life.

The Catholic Church's 1758 Index of Prohibited Books omitted the general prohibition of works defending heliocentrism,[18] but retained the specific prohibitions of the original uncensored versions of De revolutionibus and Galileo's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. Those prohibitions were finally dropped from the 1835 Index.[19]

The Inquisition's ban on reprinting Galileo's works was lifted in 1718 when permission was granted to publish an edition of his works (excluding the condemned Dialogue) in Florence.[20] In 1741 Pope Benedict XIV authorized the publication of an edition of Galileo's complete scientific works[21] which included a mildly censored version of the Dialogue.[22] In 1758 the general prohibition against works advocating heliocentrism was removed from the Index of prohibited books, although the specific ban on uncensored versions of the Dialogue and Copernicus's De Revolutionibus remained.[23] All traces of official opposition to heliocentrism by the Church disappeared in 1835 when these works were finally dropped from the Index.[24]

In 1939 Pope Pius XII, in his first speech to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, within a few months of his election to the papacy, described Galileo as being among the "most audacious heroes of research ... not afraid of the stumbling blocks and the risks on the way, nor fearful of the funereal monuments"[25] His close advisor of 40 years, Professor Robert Leiber wrote: "Pius XII was very careful not to close any doors (to science) prematurely. He was energetic on this point and regretted that in the case of Galileo."[26]

On 15 February 1990, in a speech delivered at the Sapienza University of Rome,[27] Cardinal Ratzinger (later to become Pope Benedict XVI) cited some current views on the Galileo affair as forming what he called "a symptomatic case that permits us to see how deep the self-doubt of the modern age, of science and technology goes today."[28] Some of the views he cited were those of the philosopher Paul Feyerabend, whom he quoted as saying “The Church at the time of Galileo kept much more closely to reason than did Galileo himself, and she took into consideration the ethical and social consequences of Galileo's teaching too. Her verdict against Galileo was rational and just and the revision of this verdict can be justified only on the grounds of what is politically opportune.”[28] The Cardinal did not clearly indicate whether he agreed or disagreed with Feyerabend's assertions. He did, however, say "It would be foolish to construct an impulsive apologetic on the basis of such views."[28]

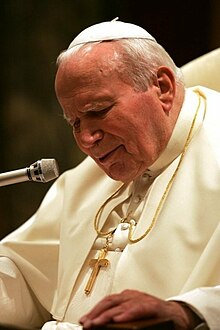

On 31 October 1992, Pope John Paul II expressed regret for how the Galileo affair was handled, and issued a declaration acknowledging the errors committed by the Church tribunal that judged the scientific positions of Galileo Galilei, as the result of a study conducted by the Pontifical Council for Culture.[29][30] In March 2008 the Vatican proposed to complete its rehabilitation of Galileo by erecting a statue of him inside the Vatican walls.[31] In December of the same year, during events to mark the 400th anniversary of Galileo's earliest telescopic observations, Pope Benedict XVI praised his contributions to astronomy.[32]

Evolution

— John Paul II, 1996[33]

Since the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859, the position of the Catholic Church on the theory of evolution has slowly been refined. For about 100 years, there was no authoritative pronouncement on the subject, though many hostile comments were made by local church figures. In contrast with Protestant literalist objections, Catholic issues with evolutionary theory have had little to do with maintaining the literalism of the account in the Book of Genesis, and have always been concerned with the question of how man came to have a soul. Modern Creationism has had little Catholic support. In the 1950s, the Church's position was one of neutrality; by the late 20th century its position evolved to one of general acceptance in recent years. Today[update], the Church's official position is a fairly non-specific example of theistic evolution.,[34][35] stating that faith and scientific findings regarding human evolution are not in conflict, though humans are regarded as a special creation, and that the existence of God is required to explain both monogenism and the spiritual component of human origins. No infallible declarations by the Pope or an Ecumenical Council have been made.

There have been several organizations composed of Catholic laity and clergy which have advocated positions both supporting evolution and opposed to evolution. For example:

- The Kolbe Center for the Study of Creation operates out of Mt. Jackson, Virginia and is a Catholic lay apostolate promoting creationism.[36]

- The "Faith Movement" was founded by Catholic Fr. Edward Holloway in Surrey, England[37] and "argues from Evolution as a fact, that the whole process would be impossible without the existence of the Supreme Mind we call God."[38]

- The "Daylight Origins Society" was founded in 1971 by John G. Campbell (d.1983) as the "Counter Evolution Group". Its goal is "to inform Catholics and others of the scientific evidence supporting Special Creation as opposed to Evolution, and that the true discoveries of Science are in conformity with Catholic doctrines." It publishes the "Daylight" newsletter.[39]

The Church does not argue with scientists on matters such as the age of the earth and the authenticity of the fossil record, seeing such matters as outside its area of expertise. Papal pronouncements, along with commentaries by cardinals, indicate that the Church is aware of the general findings of scientists on the gradual appearance of life. The Church's stance is that the temporal appearance of life has been guided by God, but the Church has thus far declined to define in what way that may be.

As in other countries, Catholic schools in the United States teach evolution as part of their science curriculum. They teach the fact that evolution occurs and the modern evolutionary synthesis, which is the scientific theory that explains why evolution occurs. This is the same evolution curriculum that secular schools teach. Bishop DiLorenzo of Richmond, chair of the Committee on Science and Human Values in a December 2004 letter sent to all U.S. bishops: "...Catholic schools should continue teaching evolution as a scientific theory backed by convincing evidence. At the same time, Catholic parents whose children are in public schools should ensure that their children are also receiving appropriate catechesis at home and in the parish on God as Creator. Students should be able to leave their biology classes, and their courses in religious instruction, with an integrated understanding of the means God chose to make us who we are."[40]

Providentissimus Deus

Providentissimus Deus, "On the Study of Holy Scripture", was an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 18 November 1893. In it, he reviewed the history of Bible study from the time of the Church Fathers to the present, spoke against what he considered to be the errors of the Rationalists and "higher critics", and outlined principles of scripture study and guidelines for how scripture was to be taught in seminaries. He also addressed the issues of apparent contradictions between the Bible and physical science, or between one part of scripture and another, and how such apparent contradictions can be resolved.

Providentissimus Deus responded to two challenges to biblical authority, both of which rose up during the 19th century.

The physical sciences, especially the theory of evolution and geology's theory of a very old earth, challenged the traditional Biblical account of creation taking place 6,000 years ago.

Pope Leo XIII wrote that true science cannot contradict scripture when it is properly explained, that errors the Church Fathers made do not demonstrate error in Scripture, and that what seems to be proved by science can turn out to be wrong.

The historical-critical method of analyzing scripture questioned the reliability of the Bible. Leo acknowledged the possibility of errors introduced by scribes but forbade the interpretation that only some of scripture is inerrant, while other elements are fallible. Leo condemned that use that certain scholars made of new evidence, clearly referring to Alfred Firmin Loisy and Maurice d'Hulst, although not by name.[41]

At first, both conservatives and liberals found elements in the encyclical to which to appeal. Over the next decade, however, Modernism spread and Providentissimus Deus was increasingly interpreted in a conservative sense.[41]

This encyclical was part of an ongoing conflict between Modernists and conservatives. In 1902, Pope Leo XIII instituted the Pontifical Biblical Commission, which was to adapt Roman Catholic Biblical studies to modern scholarship and to protect Scripture against attacks.[42]

Humani generis

Humani generis is a papal encyclical that Pope Pius XII promulgated on 12 August 1950 "concerning some false opinions threatening to undermine the foundations of Catholic Doctrine". Theological opinions and doctrines known as Nouvelle Théologie or neo-modernism and their consequences on the Church were its primary subject. Evolution and its impact on theology, constitute only two out of 44 parts. Yet the position which Pius XII defined in 1950, delinking the creation of body and soul, has been fully confirmed by Pope John Paul II, who highlighted additional facts supporting the theory of evolution half a century later. It is still accepted Church doctrine.

Current Church doctrine

In his 1893 encyclical, Pope Leo XIII wrote "no real disagreement can exist between the theologian and the scientist provided each keeps within his own limits. . . . If nevertheless there is a disagreement . . . it should be remembered that the sacred writers, or more truly ‘the Spirit of God who spoke through them, did not wish to teach men such truths (as the inner structure of visible objects) which do not help anyone to salvation’; and that, for this reason, rather than trying to provide a scientific exposition of nature, they sometimes describe and treat these matters either in a somewhat figurative language or as the common manner of speech those times required, and indeed still requires nowadays in everyday life, even amongst most learned people".[43]

The Catechism of the Catholic Church asserts: "Methodical research in all branches of knowledge, provided it is carried out in a truly scientific manner and does not override moral laws, can never conflict with the faith, because the things of the world and the things the of the faith derive from the same God. The humble and persevering investigator of the secrets of nature is being led, as it were, by the hand of God in spite of himself, for it is God, the conserver of all things, who made them what they are".[44]

Sponsorship of scientific research

A significant number of important contributions to science have been made by Catholic priests, especially Jesuit priests.[45]

Jesuits

Although the Society of Jesus has been renowned for its educational institutions and sponsored much scientific work since its inception in 1540, it has been widely perceived[who?] as having impeded the development of modern science. The Jesuit educational system was considered to be conservative and antithetical to creative thought, while the Order and its members were blamed for the Church's opposition to scientific activity and progress. However, recent scholarship in the history of science has focused on the substantial contributions of Jesuit scientists over the centuries while recognizing the constraints under which they operated.

According to Jonathan Wright, the Jesuits

contributed to the development of pendulum clocks, pantographs, barometers, reflecting telescopes and microscopes, to scientific fields as various as magnetism, optics and electricity. They observed, in some cases before anyone else, the colored bands on Jupiter’s surface, the Andromeda nebula and Saturn’s rings. They theorized about the circulation of the blood (independently of Harvey), the theoretical possibility of flight, the way the moon effected the tides, and the wave-like nature of light. Star maps of the southern hemisphere, symbolic logic, flood-control measures on the Po and Adige rivers, introducing plus and minus signs into Italian mathematics – all were typical Jesuit achievements, and scientists as influential as Fermat, Huygens, Leibniz and Newton were not alone in counting Jesuits among their most prized correspondents.[46]

The contribution of the Jesuits to the development of seismology and seismic prospecting has been so substantial that Seismology has been called "The Jesuit Science".[45] Frederick Odenbach, S.J. is considered by many to have been the "pioneer of American seismologists". In 1936, Fr. J.B. Macelwane, S.J., wrote the first seismology textbook in America, Introduction to Theoretical Seismology.

Pontifical Academy of Sciences

The Pontifical Academy of Sciences was founded in 1936 by Pope Pius XI. It is placed under the protection of the reigning Supreme Pontiff (the current Pope). Its aim is to promote the progress of the mathematical, physical and natural sciences and the study of related epistemological problems. The Academy has its origins in the Accademia Pontificia dei Nuovi Lincei ("Pontifical Academy of the New Lynxes"), founded in 1847 intended as a more closely supervised successor to the Accademia dei Lincei ("Academy of Lynxes") established in Rome in 1603, by the learned Roman Prince, Federico Cesi (1585–1630) who was a young botanist and naturalist, and which claimed Galileo Galilei as its president. The Academy has an international membership which includes British physicist Stephen Hawking and Nobel laureates such as U.S. physicist Charles Hard Townes.

Vatican Observatory

The Vatican Observatory (Specola Vaticana) is an astronomical research and educational institution supported by the Holy See. Originally based in Rome, it now has headquarters and laboratory at the summer residence of the Pope in Castel Gandolfo, Italy, and an observatory at the Mount Graham International Observatory in the United States.[47] The Director of the Observatory is Fr. José Gabriel Funes, SJ. Many distinguished scholars have worked at the Observatory. In 2008, the Templeton Prize was awarded to cosmologist Fr. Michał Heller, a Vatican Observatory Adjunct Scholar. In 2010, the George Van Biesbroeck Prize was awarded to former observatory director Fr. George Coyne, SJ.[48]

Conflict thesis and "drastic revision"

The scientist John William Draper and the intellectual Andrew Dickson White were the most influential exponents of the conflict thesis between the Roman Catholic Church and science. In the early 1870s, Draper was invited to write a History of the Conflict between Religion and Science (1874), a book replying to contemporary papal edicts such as the doctrine of infallibility, and mostly criticizing the anti-intellectualism of Roman Catholicism, [49] yet he assessed that Islam and Protestantism had little conflict with science. Draper’s preface summarises the conflict thesis: "The history of Science is not a mere record of isolated discoveries; it is a narrative of the conflict of two contending powers, the expansive force of the human intellect on one side, and the compression arising from traditionary faith and human interests on the other."[50] In 1896, White published the History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom, the culmination of thirty years of research and publication on the subject. In the introduction, White emphasized he arrived at his position after the difficulties of assisting Ezra Cornell in establishing a university without any official religious affiliation.

More recently, Thomas E. Woods, Jr. asserts that, despite the widely held conception of the Catholic Church as being anti-science, this conventional wisdom has been the subject of "drastic revision" by historians of science over the last 50 years. Woods asserts that the mainstream view now is that the "Church [has] played a positive role in the development of science ... even if this new consensus has not yet managed to trickle down to the general public".[45]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b c Noble, p. 582, pp. 593–595.

- ^ Woods, p. 102.

- ^ a b Hans Thijssen (2003-01-30). "Condemnation of 1277". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. University of Stanford. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ^ a b Woods, p 91-92

- ^ Schönberg, Nicholas, Letter to Nicolaus Copernicus, translated by Edward Rosen.

- ^ Koyré (1973, pp. 27, 90) and Rosen (1995, pp. 64,184) take the view that Copernicus was indeed concerned about possible objections from theologians, while Lindberg and Numbers (1986) argue against it. Koestler (1963) also denies it. Indirect evidence that Copernicus was concerned about objections from theologians comes from a letter written to him by Andreas Osiander in 1541, in which Osiander advises Copernicus to adopt a proposal by which he says "you will be able to appease the Peripatetics and theologians whose opposition you fear." (Koyré, 1973, pp. 35, 90)

- ^ Rosen (1995, pp.151–59)

- ^ Rosen (1995, p.158)

- ^ Schmitt, p. 46,

- ^ "Conran Gesner biography". Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ^ Mason, Michael (18 August 2008). "How to Teach Science to the Pope". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ Sharratt (1994, pp.127–131), McMullin (2005a).

- ^ In fact, in the Pythagorean cosmological system the Sun was not motionless.

- ^ Decree of the General Congregation of the Index, March 5, 1616, translated from the Latin by Finocchiaro (1989, pp.148-149). An on-line copy of Finocchiaro's translation has been made available by Gagné (2005).

- ^ Fantoli (2005, pp.118–19); Finocchiaro (1989, pp.148, 153). On-line copies of Finocchiaro's translations of the relevant documents, Inquisition Minutes of 25 February, 1616 and Cardinal Bellarmine's certificate of 26 May, 1616, have been made available by Gagné (2005). This notice of the decree would not have prevented Galileo from discussing heliocentrism solely as a mathematical hypothesis, but a stronger formal injunction (Finocchiaro, 1989, p.147-148) not to teach it "in any way whatever, either orally or in writing", allegedly issued to him by the Commissary of the Holy Office, Father Michelangelo Segizzi, would certainly have done so (Fantoli, 2005, pp.119–20, 137). There has been much controversy over whether the copy of this injunction in the Vatican archives is authentic; if so, whether it was ever issued; and if so, whether it was legally valid (Fantoli, 2005, pp.120–43).

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ From the Inquisition's sentence of June 22, 1633 (de Santillana, 1976, pp.306-10; Finocchiaro 1989, pp. 287-91)

- ^ Heilbron (2005, p. 307); Coyne (2005, p. 347).

- ^ McMullin (2005, p. 6); Coyne (2005, pp. 346-47).

- ^ Heilbron (2005, p.299).

- ^ Two of his non-scientific works, the letters to Castelli and the Grand Duchess Christina, were explicitly not allowed to be included (Coyne 2005, p.347).

- ^ Heilbron (2005, p.303–04); Coyne (2005, p.347). The uncensored version of the Dialogue remained on the Index of prohibited books, however (Heilbron 2005, p.279).

- ^ Heilbron (2005, p.307); Coyne (2005, p.347) The practical effect of the ban in its later years seems to have been that clergy could publish discussions of heliocentric physics with a formal disclaimer assuring its hypothetical character and their obedience to the church decrees against motion of the earth: see for example the commented edition (1742) of Newton's 'Principia' by Fathers Le Seur and Jacquier, which contains such a disclaimer ('Declaratio') before the third book (Propositions 25 onwards) dealing with the lunar theory.

- ^ McMullin (2005, p.6); Coyne (2005, p.346). In fact, the Church's opposition had effectively ended in 1820 when a Catholic canon, Giuseppe Settele, was given permission to publish a work which treated heliocentism as a physical fact rather than a mathematical fiction. The 1835 edition of the Index was the first to be issued after that year.

- ^ Discourse of His Holiness Pope Pius XII given on 3 December 1939 at the Solemn Audience granted to the Plenary Session of the Academy, Discourses of the Popes from Pius XI to John Paul II to the Pontifical Academy of the Sciences 1939-1986, Vatican City, p.34

- ^ Robert Leiber, Pius XII Stimmen der Zeit, November 1958 in Pius XII. Sagt, Frankfurt 1959, p.411

- ^ An earlier version had been delivered on 16 December 1989, in Rieti, and a later version in Madrid on 24 February 1990 (Ratzinger, 1994, p.81). According to Feyerabend himself, Ratzinger had also mentioned him "in support of" his own views in a speech in Parma around the same time (Feyerabend, 1995, p.178).

- ^ a b c Ratzinger (1994, p.98).

- ^ "Vatican admits Galileo was right". New Scientist. 1992-11-07. Retrieved 2007-08-09..

- ^ "Papal visit scuppered by scholars". BBC News. 2008-01-15. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ Owen, Richard; Delaney, Sarah (2008-03-04). "Vatican recants with a statue of Galileo". London: TimesOnline News. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- ^ "Pope praises Galileo's astronomy". BBC News. 2008-12-21. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ John Paul II, Message to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences on Evolution

- ^ Catholic Answers (Impratur Robert H. Brom, Bishop of San Diego). "Adam, Eve, and Evolution". Catholic Answers. Catholic.com. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ Warren Kurt VonRoeschlaub. "God and Evolution". Talk Origins Archive. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ Kolbe Center for the Study of Creation: Defending Genesis from a Traditional Catholic Perspective official website.

- ^ Catholicism: a New Synthesis, Edward Holloway, 1969.

- ^ Theistic Evolution and the Mystery of FAITH (cont'd), Anthony Nevard, Theotokos Catholic Books website; Creation/Evolution Section.

- ^ Daylight Origins Society: Creation Science for Catholics official homepage.

- ^ Catholic schools steer clear of anti-evolution bias, Jeff Severns Guntzel, National Catholic Reporter, March 25, 2005

- ^ a b "Provdentissimus Deus." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ "Biblical Commission." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ (Leo XIII, Providentissimus Deus 18)

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church 159

- ^ a b c "How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization". Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ^ Wright, Jonathan (2004). The Jesuits. p. 189.

- ^ Johnson, George (2009-06-22). "Vatican's Celestial Eye, Seeking Not Angels but Data". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ Dennis Sadowski (2010-01-04). "American Astronomical Society honors former Vatican Observatory head". Catholic News Service. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ^ Alexander, D (2001), Rebuilding the Matrix, Lion Publishing, ISBN 0-7459-5116-3 (pg. 217)

- ^ John William Draper, History of the Conflict Religion, D. Appleton and Co. (1881)

References

- Appleby, R. Scott. Between Americanism and Modernism; John Zahm and Theistic Evolution, in Critical Issues in American Religious History: A Reader, Ed. by Robert R. Mathisen, 2nd revised edn., Baylor University Press, 2006, ISBN 1-932792-39-2, 9781932792393. Google books

- Artigas, Mariano; Glick, Thomas F., Martínez, Rafael A.; Negotiating Darwin: the Vatican confronts evolution, 1877-1902, JHU Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8018-8389-X, 9780801883897, Google books

- Harrison, Brian W., Early Vatican Responses to Evolutionist Theology, Living Tradition, Organ of the Roman Theological Forum, May 2001.

- O'Leary, John. Roman Catholicism and modern science: a history, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006, ISBN 0-8264-1868-6, 9780826418685 Google books

Further reading

- Bennett, Gaymon, Hess, Peter M. J. and others, The Evolution of Evil, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, ISBN 3-525-56979-3, 9783525569795, Google books

- Johnston, George (1998). Did Darwin Get It Right?. Huntington: Our Sunday Visitor. ISBN 0879739452. (google books)

- Kung, Hans, The beginning of all things: science and religion, trans. John Bowden, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007, ISBN 0-8028-0763-1, 9780802807632. Google books

- Olson, Richard, Science and religion, 1450-1900: from Copernicus to Darwin, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, ISBN 0-313-32694-0, 9780313326943. Google books

External links

- Galileo Galilei, Scriptural Exegete, and the Church of Rome, Advocate of Science lecture (audio here) by Thomas Aquinas College tutor Dr. Christopher Decaen

- "The End of the Myth of Galileo Galilei" by Atila Sinke Guimarães

- Vatican Council I (1869-70), the full documents.

- 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia: Catholics and Evolution and Evolution, History and Scientific Foundation of

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Pope Pius XII, Humani Generis 1950 encyclical

- Roberto Masi, "The Credo of Paul VI: Theology of Original Sin and the Scientific Theory of Evolution" (L'Osservatore Romano, 17 April 1969).

- Pope John Paul II, general audience of 10 July 1985. "Proofs for God's Existence are Many and Convergent."

- Cardinal Ratzinger's Commentary on Genesis Excerpts from In the Beginning: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall.

- International Theological Commission (2004). "Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons Created in the Image of God."

- Mark Brumley, "Evolution and the Pope, of Ignatius Insight

- John L. Allen Teaching of Benedict XVI on Evolution before becoming Pope.

- Benedict XVI's inaugural address.

- Pontifical Academy of Sciences