Banana republic: Difference between revisions

m Bot: link syntax/spacing |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

A '''banana republic''' is a politically unstable country that economically depends upon the exports of a limited resource (fruits, minerals), and usually features a society composed of [[Social stratification|stratified]] [[Class (social)|social classes]] — a great, impoverished [[working class]] and a ruling [[plutocracy]], composed of the élites of business, politics, and the military.<ref>{{Cite book|author = Richard Alan White |title = The Morass. United States Intervention in Central America|url=http://books.google.it/books?id=X88WAAAAYAAJ&hl=en|publisher = Harper & Row|location = New York|year = 1984| pages = 319}} [http://www.google.it/search?num=100&hl=en&safe=off&tbm=bks&q=%22Richard+Alan+White%22+%22The+morass%22+%22United+States+intervention+in+Central+America%22+%22banana+republic%22 P. 95]. ISBN 0-060-91145-X; ISBN 978-0-06091-145-4.</ref> In [[political science]], the term ''banana republic'' denotes a country dependent upon limited [[Primary sector of the economy|primary-sector productions]], which is ruled by a [[plutocracy]] who exploit the national economy by means of a politico-economic [[oligarchy]].<ref name="GREED">{{cite journal |title=Big-business Greed Killing the Banana (p. A19)|journal=The Independent, via ''[[The New Zealand Herald]]'' |url=http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-179318358.html |date=Saturday 24 May 2008 |accessdate=Sunday 24 June 2012}}</ref> In [[American literature]], the term ''banana republic'' originally denoted the fictional "Republic of Anchuria", a "servile dictatorship" that abetted, or supported for [[Political corruption#Kickbacks|kickbacks]], the exploitation of large-scale plantation agriculture, especially banana cultivation.<ref name="GREED"/> In U.S. politics, the term ''[[wiktionary:banana republic|banana republic]]'' is a pejorative political descriptor coined by the American writer [[O. Henry]] in ''Cabbages and Kings'' (1904), a book of thematically related short stories derived from his 1896–97 residence in [[Honduras]], where he was hiding from U.S. law for bank [[embezzlement]].<ref>[http://www.google.it/search?num=100&hl=en&safe=off&tbm=bks&q=O.+Henry+was+first+to+use+the+term+%22banana+republic%22+%22Cabbages+and+Kings%22+%281904%29 ''Occurrences''] on Google Books.</ref><ref>{{Cite book|author = O. Henry|title = Cabbages and Kings|url=http://books.google.it/books?id=6jpMsL2T0CoC&hl=en|publisher = Doubleday, Page & Co. for Review of Reviews Co|location = New York|year = 1904| pages = 312}} [http://books.google.it/books?id=CsSr5CxBrGQC&hl=en&pg=PT198&dq=%22While+he+was+in+Honduras,+Porter+coined+the+term%22+%22banana+republic%22#v=onepage&q=%22While%20he%20was%20in%20Honduras%2C%20Porter%20coined%20the%20term%22%20%22banana%20republic%22&f=false "While he was in Honduras, Porter coined the term 'banana republic'"].</ref> |

A '''banana republic''' is a politically unstable country that economically depends upon the exports of a limited resource (fruits, minerals), and usually features a society composed of [[Social stratification|stratified]] [[Class (social)|social classes]] — a great, impoverished [[working class]] and a ruling [[plutocracy]], composed of the élites of business, politics, and the military.<ref>{{Cite book|author = Richard Alan White |title = The Morass. United States Intervention in Central America|url=http://books.google.it/books?id=X88WAAAAYAAJ&hl=en|publisher = Harper & Row|location = New York|year = 1984| pages = 319}} [http://www.google.it/search?num=100&hl=en&safe=off&tbm=bks&q=%22Richard+Alan+White%22+%22The+morass%22+%22United+States+intervention+in+Central+America%22+%22banana+republic%22 P. 95]. ISBN 0-060-91145-X; ISBN 978-0-06091-145-4.</ref> In [[political science]], the term ''banana republic'' denotes a country dependent upon limited [[Primary sector of the economy|primary-sector productions]], which is ruled by a [[plutocracy]] who exploit the national economy by means of a politico-economic [[oligarchy]].<ref name="GREED">{{cite journal |title=Big-business Greed Killing the Banana (p. A19)|journal=The Independent, via ''[[The New Zealand Herald]]'' |url=http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-179318358.html |date=Saturday 24 May 2008 |accessdate=Sunday 24 June 2012}}</ref> In [[American literature]], the term ''banana republic'' originally denoted the fictional "Republic of Anchuria", a "servile dictatorship" that abetted, or supported for [[Political corruption#Kickbacks|kickbacks]], the exploitation of large-scale plantation agriculture, especially banana cultivation.<ref name="GREED"/> In U.S. politics, the term ''[[wiktionary:banana republic|banana republic]]'' is a pejorative political descriptor coined by the American writer [[O. Henry]] in ''Cabbages and Kings'' (1904), a book of thematically related short stories derived from his 1896–97 residence in [[Honduras]], where he was hiding from U.S. law for bank [[embezzlement]].<ref>[http://www.google.it/search?num=100&hl=en&safe=off&tbm=bks&q=O.+Henry+was+first+to+use+the+term+%22banana+republic%22+%22Cabbages+and+Kings%22+%281904%29 ''Occurrences''] on Google Books.</ref><ref>{{Cite book|author = O. Henry|title = Cabbages and Kings|url=http://books.google.it/books?id=6jpMsL2T0CoC&hl=en|publisher = Doubleday, Page & Co. for Review of Reviews Co|location = New York|year = 1904| pages = 312}} [http://books.google.it/books?id=CsSr5CxBrGQC&hl=en&pg=PT198&dq=%22While+he+was+in+Honduras,+Porter+coined+the+term%22+%22banana+republic%22#v=onepage&q=%22While%20he%20was%20in%20Honduras%2C%20Porter%20coined%20the%20term%22%20%22banana%20republic%22&f=false "While he was in Honduras, Porter coined the term 'banana republic'"].</ref> |

||

In practice, a banana republic is a country operated as a commercial enterprise for [[Private property|private]] [[Profit (economics)|profit]], effected by the collusion between the State and favoured [[monopoly|monopolies]], whereby the profits derived from private exploitation of public lands is private property, and the debts incurred are public responsibility. Such an imbalanced [[economy]] reduces the national [[currency]] to devalued [[Banknotes|paper-money]], hence, the country is ineligible for international development-credit, and remains limited by the [[Uneven and combined development|uneven economic development]] of town and country.<ref name=Hitchens >{{cite journal |author=Christopher Hitchens |title=America the Banana Republic|journal=''[[Vanity Fair (magazine)|Vanity Fair]]'' |url=http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2008/10/hitchens200810 |date=9 October 2008 |accessdate=Sunday 24 June 2012}}</ref> [[Kleptocracy]], government by thieves, features influential government employees exploiting their posts for personal gain (embezzlement, fraud, bribery, etc.), with the resultant [[government budget deficit]] repaid by the native [[working class|working people]] who "earn money”, rather than “make money”. Because of foreign ([[multinational corporation|corporate]]) manipulation, the kleptocratic government is unaccountable to its nation, the country’s private sector–public sector corruption operates the banana republic, thus, the national legislature usually are for sale, and function mostly as ceremonial government.<ref name=Hitchens /> |

In practice, a banana republic [[state_capitalism|is a country operated as a commercial enterprise]] for [[Private property|private]] [[Profit (economics)|profit]], effected by the collusion between the State and favoured [[monopoly|monopolies]], whereby the profits derived from private exploitation of public lands is private property, and the debts incurred are public responsibility. Such an imbalanced [[economy]] reduces the national [[currency]] to devalued [[Banknotes|paper-money]], hence, the country is ineligible for international development-credit, and remains limited by the [[Uneven and combined development|uneven economic development]] of town and country.<ref name=Hitchens >{{cite journal |author=Christopher Hitchens |title=America the Banana Republic|journal=''[[Vanity Fair (magazine)|Vanity Fair]]'' |url=http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2008/10/hitchens200810 |date=9 October 2008 |accessdate=Sunday 24 June 2012}}</ref> [[Kleptocracy]], government by thieves, features influential government employees exploiting their posts for personal gain (embezzlement, fraud, bribery, etc.), with the resultant [[government budget deficit]] repaid by the native [[working class|working people]] who "earn money”, rather than “make money”. Because of foreign ([[multinational corporation|corporate]]) manipulation, the kleptocratic government is unaccountable to its nation, the country’s private sector–public sector corruption operates the banana republic, thus, the national legislature usually are for sale, and function mostly as ceremonial government.<ref name=Hitchens /> |

||

==The concept== |

==The concept== |

||

Revision as of 00:50, 15 August 2012

A banana republic is a politically unstable country that economically depends upon the exports of a limited resource (fruits, minerals), and usually features a society composed of stratified social classes — a great, impoverished working class and a ruling plutocracy, composed of the élites of business, politics, and the military.[1] In political science, the term banana republic denotes a country dependent upon limited primary-sector productions, which is ruled by a plutocracy who exploit the national economy by means of a politico-economic oligarchy.[2] In American literature, the term banana republic originally denoted the fictional "Republic of Anchuria", a "servile dictatorship" that abetted, or supported for kickbacks, the exploitation of large-scale plantation agriculture, especially banana cultivation.[2] In U.S. politics, the term banana republic is a pejorative political descriptor coined by the American writer O. Henry in Cabbages and Kings (1904), a book of thematically related short stories derived from his 1896–97 residence in Honduras, where he was hiding from U.S. law for bank embezzlement.[3][4]

In practice, a banana republic is a country operated as a commercial enterprise for private profit, effected by the collusion between the State and favoured monopolies, whereby the profits derived from private exploitation of public lands is private property, and the debts incurred are public responsibility. Such an imbalanced economy reduces the national currency to devalued paper-money, hence, the country is ineligible for international development-credit, and remains limited by the uneven economic development of town and country.[5] Kleptocracy, government by thieves, features influential government employees exploiting their posts for personal gain (embezzlement, fraud, bribery, etc.), with the resultant government budget deficit repaid by the native working people who "earn money”, rather than “make money”. Because of foreign (corporate) manipulation, the kleptocratic government is unaccountable to its nation, the country’s private sector–public sector corruption operates the banana republic, thus, the national legislature usually are for sale, and function mostly as ceremonial government.[5]

The concept

The banana republic, a country with a single-purpose economy, originated with the introduction of the banana fruit to Europe in 1870, by Captain Lorenzo D. Baker, of the ship The Telegraph, who initially bought bananas in Jamaica and sold them in Boston at a 1,000 per cent profit.[6] Dietarily, the banana proved a popular food with Americans, because it was a nutritious tropical fruit cheaper in price than local U.S. fruit, such as the apple; in 1913, a dozen bananas sold for twenty-five cents, while the same quarter-dollar-money bought only two apples.[7] Yet the banana business was incidentally established, by the American railroad tycoons Henry Meiggs and his nephew, Minor C. Keith, who, in 1873, established banana plantations — initially along the railroads proper — to produce food-stuffs with which to feed the men working on the railroad. Upon grasping the potential profitability of exporting to and selling bananas in the U.S., Meiggs and Keith then exported the fruit to the Southeastern United States.[8]

In the mid-1870s, to manage the new industrial-agriculture business enterprise in the countries of Central America, Keith founded the Tropical Trading and Transport Company; one-half of the future United Fruit Company (Chiquita Brands International), created in 1899, by corporate merger with the Boston Fruit Company, owned by Andrew Preston. By the 1930s, the international influence (political and economic) of the United Fruit Company granted it control of 80–90 per cent of the U.S. banana trade.[9] Nonetheless, despite the UFC monopoly, in 1924, the Vaccaro Brothers established the Standard Fruit Company (Dole Food Company) to export Honduran bananas to the port of New Orleans, in the Gulf of Mexico coast of the U.S. The fruit exporters profited from such low U.S. prices because the banana companies, by their manipulation of the national land use laws of the producing countries, were able to cheaply buy large tracts of prime agricultural land for banana plantations in the countries of the Caribbean Basin, the Central American isthmus, and the tropical South American countries; and employ the native peoples as cheap-wage, manual labourers, after having rendered them landless, by means of legalistic dispossession.[8]

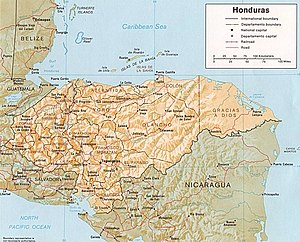

Moreover, by the late 19th century, three American multinational corporations — the United Fruit Company, the Standard Fruit Company, and the Cuyamel Fruit Company — dominated the cultivation, harvesting, and exportation of bananas, and controlled the road, rail, and port infrastructure of Honduras. In the north coast, on the Caribbean Sea, the Honduran government ceded to the banana companies 500 hectares (1,235.52 acres) for each kilometre of railroad laid; yet there was no passenger or freight railroad to Tegucigalpa, the national capital city. To Honduran people, the United Fruit Company was El Pulpo, The Octopus, that economically pervaded their society, controlled their country’s transport infrastructure, and sometimes violently manipulated the national politics of the Republic of Honduras.[10]

Exemplar republics

Honduras

In the early 20th century, instrumental to establishing the “banana republic” stereotype was the American businessman Sam Zemurray, founder of the Cuyamel Fruit Company, who had entered the banana-export business by buying over-ripe bananas from the United Fruit Company, to sell in New Orleans. In 1910, he bought 6,070 hectares (15,000 acres) of the Caribbean coast of Honduras for agricultural exploitation, by the Cuyamel Fruit Company. In 1911, Zemurray concorded a business and political alliance with Manuel Bonilla, an ex-President of Honduras (1904–07); and with General Lee Christmas, an American mercenary soldier, to unilaterally change the republican government of Honduras.

As planned, the mercenary army of the Cuyamel Fruit Company, commanded by Gen. Christmas, executed and realized a coup d’état against President Miguel R. Dávila (1907–11), and, in his stead, installed General Manuel Bonilla as President of Honduras (1912–13). The U.S. Government ignored the private-army deposition of the elected government of Honduras, because the State Department distrusted President Dávila for being politically too-liberal, and for being a poor businessman, whose management decisions had got the Republic of Honduras too-indebted to Great Britain — an unacceptable geopolitical risk for the U.S. in the Western Hemisphere. Moreover, domestically, the Dávila Government had slighted the Cuyamel Fruit Company, when it colluded with the rival United Fruit Company, and had awarded the UFC a banana-trade monopoly, in exchange for the fruit company brokering U.S. Government loans for the Honduran government.[11][12]

The resultant political instability, halted economy, and great external debt (ca. $4 billion), excluded the Republic of Honduras from international capital investment; such financial deficit continued the economic stagnation; and so perpetuated the banana republic image of Honduras.[13] With the native government hobbled with an historical, inherited foreign debt, such fiscal weakness undermined the Honduran Government’s functions, and so allowed foreign multinational corporations to manage the country and the people of Honduras more effectively and efficiently — especially because the fruit companies had built, and thus controlled, the Honduran infrastructure (road, rail, port); had established long-distance communications (telegraph, telephone); and so were the principal employers in the economy of Honduras. In the event, the U.S. dollar became the legal-tender currency of Honduras; the mercenary Gen. Lee Christmas became Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Honduras, and later was appointed U.S. Consul to the Republic of Honduras.[14] Nonetheless, twenty-three years later, by means of a hostile takeover, Sam Zemurray assumed control of the rival United Fruit Company, in 1933.[15]

Guatemala

Guatemala suffered the regional socio-economic legacy of the banana republic: inequitably distributed agricultural land and natural wealth, uneven economic development, and an economy dependent upon a few export crops — usually bananas, coffee, sugar cane. The inequitable land distribution is the principal cause of national poverty and the low quality of Guatemalan life, and the concomitant socio-political discontent and insurrection. Almost 90 per cent of the country's farms are too small to yield adequate subsistence harvests to the farmers, whilst two per cent of the country's farms occupy 65 per cent of the arable land, property of the local oligarchy. [citation needed]

In the middle of the 20th century, during the 1950s, the United Fruit Company convinced the governments of U.S. presidents Harry Truman (1945–53) and Dwight Eisenhower (1953–61) that the popular, elected government of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán of Guatemala was secretly pro–Soviet, for having expropriated unused “fruit company lands” to landless peasants. In the Cold War (1945–91) context, of the pro-active anti-Communism of the Senator McCarthy era of U.S. national politics (1947–57), such a geopolitical consideration, about the “security” of the Western Hemisphere, facilitated President Eisenhower’s ordering and authorising Operation PBSUCCESS, the Guatemalan coup d’état (1954), by means of which the Central Intelligence Agency deposed the elected Government (1950–54) of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, and installed the pro-business government of Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas (1954–57), which perdured for three years, until his assassination by a presidential guard.[2]

A mixed history of elected presidents and puppet-master military juntas were the governments of Guatemala in the course of the thirty-six-year Guatemalan Civil War (1960–96). Moreover, in 1986, at the twenty-six-year mark, the Guatemalan people promulgated a new political constitution, and elected Vinicio Cerezo (1986–91) president; then Jorge Serrano Elías (1991–93).[16]

The banana republic in art

In the encyclopædic, historical poetry in the book Canto General (General Song, 1950), the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1904–73) denounced foreign multinational corporate political dominance of Latin American countries with the four-stanza poem “La United Fruit Co.”; the second-stanza excerpts read:[17]

. . . The Fruit Company, Inc.

Reserved for itself the most succulent,

The central coast of my own land,

The delicate waist of America.It rechristened its territories

As the “Banana Republics”,

And over the sleeping dead,

Over the restless heroes

Who brought about the greatness,

The liberty and the flags,

It established a comic opera. . . .

See also

- Absurdistan

- Dictator novel

- Failed state

- Kangaroo court

- McOndo

- Neo-colonialism

- Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard (1904), by Joseph Conrad

- Ruritania

- Subaltern

- William Walker

References

- ^ Richard Alan White (1984). The Morass. United States Intervention in Central America. New York: Harper & Row. p. 319. P. 95. ISBN 0-060-91145-X; ISBN 978-0-06091-145-4.

- ^ a b c "Big-business Greed Killing the Banana (p. A19)". The Independent, via The New Zealand Herald. Saturday 24 May 2008. Retrieved Sunday 24 June 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ Occurrences on Google Books.

- ^ O. Henry (1904). Cabbages and Kings. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co. for Review of Reviews Co. p. 312. "While he was in Honduras, Porter coined the term 'banana republic'".

- ^ a b Christopher Hitchens (9 October 2008). "America the Banana Republic". Vanity Fair. Retrieved Sunday 24 June 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ Alison Acker (1988). Honduras. The Making of a Banana Republic. Toronto: Between the Lines. pp. 166, p. 60. ISBN 0-919-94689-5; ISBN 978-0-91994-689-7.

- ^ Dan Koeppel (2008). Banana. The Fate of the Fruit that Changed the World. London: Hudson Street Press. pp. 281, p. 68. ISBN 1-594-63038-0; ISBN 978-1-59463-038-5.

- ^ a b Ibid., p. 60.

- ^ Alison Acker, op. cit., p. 63.

- ^ Peter Chapman (2007). Bananas. How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World. New York: Cannongate. pp. 224, p. 102. ISBN 1-841-95881-6; ISBN 978-1-84195-881-1.

- ^ Alison Acker, op. cit., p. 63.

- ^ Darío A. Euraque (1996). Reinterpreting the Banana Republic: Region and State in Honduras, 1870–1972. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 242, p. 44. ISBN 0-807-84604-X; ISBN 978-0-80784-604-9.

- ^ W.S. Valentine (November 1916). "Need for Capital in Latin America: Honduras". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 68: 185–87. JSTOR 1013083.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ George Black (1988). The Good Neighbor. How the United States Wrote the History of Central America and the Caribbean. New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 200, p. 35. ISBN 0-394-75965-6; ISBN 978-0-39475-965-4.

- ^ Peter Chapman, op. cit., p. 102.

- ^ Carol A. Smith (August 1978). "Beyond Dependency Theory: National and Regional Patterns of Underdevelopment in Guatemala". American Ethnologist. 5 (3): 574–617. doi:10.1525/ae.1978.5.3.02a00090. JSTOR 643758.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ George Black, op. cit., p. 33.

External links

- From Arbenz to Zelaya: Chiquita in Latin America - video report by Democracy Now!

- Cabbages and Kings — The O. Henry book of short stories wherein he coined the banana republic term