Historiography of Juan Manuel de Rosas: Difference between revisions

FarSouthNavy (talk | contribs) →Immediate descriptions: Rewording header |

See Juan Manuel de Rosas' talk page |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{neutrality|date=January 2013}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2012}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2012}} |

||

{{multiple image |

{{multiple image |

||

Revision as of 12:05, 9 January 2013

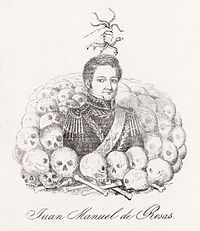

The historiography of Juan Manuel de Rosas is highly controversial. Most Argentine historians take an approach either for or against him, a dispute that influenced much of the whole historiography of Argentina.[1]

Contemporary descriptions

Rosas' government of Argentina, during the period of the civil wars, attracted wide criticism. Most leaders of the Unitarian Party exiled themselves to other countries during Rosas' rule. Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, living in Chile, wrote Facundo, a biography of Facundo Quiroga whose real intention was to attack Rosas.[2]

Most Unitarians established themselves in Montevideo. In their writings they criticized Rosas, calling him a ruthless dictator and accusing him of many crimes. These statements were not intended for merely local effect but were designed to promote a European intervention in the conflict. José Rivera Indarte wrote a work called Blood Tables (Tablas de Sangre) which was published in Europe. It was intended to be a complete list of the known victims of Rosas. It attributed more than 22,000 deaths to his government. The Argentine politician Manuel Moreno considered this work to be libel. The reports from Montevideo were echoed in France, as many French citizens resided in Montevideo at that time. Alexandre Dumas wrote the novel Montevideo, or the New Troy based on the reports of Melchor Pacheco. Adolphe Thiers urged François Guizot to intervene in the conflict. On its own initiative France imposed a blockade of the Río de la Plata between 1838 and 1840, which was followed in 1845 by a joint blockade with Great Britain.[3]

The intervention by the European powers won sympathy for Rosas from other South Americans, who saw him as a fellow American standing against powerful foreign aggressors. He was supported by Francisco Antonio Pinto, José Ballivián, and many international newspapers. Some of those newspapers were the American New York Sun (August 5, 1845) and New York Herald (September 7, 1845), the Brazilians O Brado de Amazonas (August 9, 1845) and O Sentinella da Monarchia (August 20, 1845) and the Chilean El Tiempo (August 15, 1845).[4] Even some Europeans saw him as a romantic hero.[5] The liberator José de San Martín, who was living in France, corresponded with Rosas, offering his full support, both against the Europeans and the Unitarians. San Martín showed his respect by bequeathing his sword to Rosas.[6]

Later descriptions

Rosas was deposed by Justo José de Urquiza in 1852, in the battle of Caseros, and Buenos Aires seceded from the Argentine Confederation later in the year. Rosas moved into exile in Southampton. The Unitarians confiscated all his properties and repudiated him in a variety of ways. José Mármol wrote the novel Amalia, the first Argentine novel, and included several criticisms to Rosas, such as "not even the dust of your bones the America will have". However, such authors cannot be considered exclusively from the perspectives of historiography or the history of ideas, as they were politically active people, even with main roles in the political struggles of their time; and their works were used as tools to advertise their ideas.[7] Most documents of the time were burned during the aftermath of Caseros.[8] The legislature of Buenos Aires charged him with High treason in 1857; Nicanor Arbarellos supported his vote with the following speech:

Rosas, sir, that tyrant, that barbarian, even if barbarian and cruel, was not considered as such by the European and civilized nations, and that judgment of the European and civilized nations, moved to posterity, will hold in doubt, at least, that barbarian and execrable tyranny that Rosas exercised among us. It's needed, then, to mark with a legislative sanction declaring him guilty of lèse majesté so at least this point is marked in history, and it is seen that the most potent court, which is the popular court, which is the voice of the sovereign peoples by us represented, throws to the monster the anathema calling him traitor and guilty of lèse majesté. Judgments like those must not be left for history.No, sir: they will say, the savage unitarians, his enemies, lied. He has not been a tyrant: far from that, he has been a great man, a great general. It's needed to throw without doubts this anathema to the monster. If at least we had imititated the English people, who dragged the corpse of Cromwell across the streets of London, and had dragged Rosas across the streets of Buenos Aires! I support, Mr. President, the project. If the judgment of Rosas was left to the judgment of history, we won't get Rosas to be condemned as a tyrant, but perhaps he may be in it the greatest and most glorious of Argentines.[9][A]

What will be said, what might be said in history when it's seen that the civilized nations of the world, for whom we are but just a point, have acknowledged in this tyrant a being worthy to deal with them? That England has returned his cannons taken in war action, and saluted his bloody and innocent-blood stained flag with a 21-gun salute? This fact, known by history, would be a great counterweight, Sir, if we leave Rosas without this sanction. The France itself, which started the crusade that was shared by general Lavalle, in its due time also abandoned him, dealed with Rosas and saluted his flag with a 21-gun salute. I ask, Sir, if this fact won't erase from history everything we may say, if we leave this monster that decimated us for so many years without a sanction.

The judgment of Rosas must not be left to history, as some people desire. It's clear that it can't be left to history the judgment of the tyrant Rosas. Let's throw to Rosas this anathema, which perhaps can be the only one to harm him in history, because otherwise his tyranny will always be doubtful, as well as his crimes! What will be said in history, sir? And this is sad to tell, what will be said in history when it is said that the brave Admiral Brown, the hero of the Navy of the Independence war, was the admiral who defended the tyranny of Rosas? What will be said in history without this anathema, when it is said that this man who contributed with his glories and talents to give shine to the Sun of May, that the other deputee referenced in his speech, when it is said that General San Martín, the conqueror of the Andes, the father of the Argentine glories, made him the greatest tribute that can be given to a soldier by handing him his sword? Will this be believed, sir, if we don't throw an anathema to the tyrant Rosas? Will this man be known as he is in 20 or 50 years, if we want to go further, when it is known that Brown and San Martín were loyal to him and gave him the most respectful tributes, along with France and England?

A notable exception to this trend was Juan Bautista Alberdi, who was among the Unitarian expatriates in Montevideo and attacked Rosas during his rule. He met with him during the latter's exile in England in 1857, an event which changed his mind into supporting him and even lead to becoming friends. Alberdi would condemn the aforementioned sanction against Rosas, lauded that he never plotted to regain power, compared the barbarism attributed to him with the contemporary United States, Russia, Italy and Germany, and pointed that Urquiza deposed Rosas to organize the country but the actual result was the secession of Buenos Aires.[10][11] Domingo Faustino Sarmiento changed his view of Rosas during his late life as well.[12] Bartolomé Mitre maintained his hatred towards him all his life, which may be explained by family reasons: Mitre's father was appointed as treasurer of Uruguay by Fructuoso Rivera and fired by Manuel Oribe; and Rosas supported Oribe against Rivera during the Uruguayan civil war.[13]

Bartolomé Mitre started the first remarkable historiographic studies shortly afterwards, but opted to avoid the period of Rosas rule altogether. He wrote biographies for Manuel Belgrano and José de San Martín, which actually detailed the Spanish rule in the Americas, the Argentine War of Independence and the War with Brazil, but made no mention afterwards. His biography of San Martín ended at the point when San Martín ended his military career, and he declined to write his projected book "The ostracism and apotheosis of General San Martín", as he would have to write about San Martín's disputes with Bernardino Rivadavia, his repudiation of the execution of Manuel Dorrego and the rule of Juan Lavalle, his steady appreciative correspondence to Rosas and his rejection to the European interventions against him; all of which would hint that San Martín was closer to the Federalists than to the Unitarians.[14] Similarly, Mitre wrote a series of small biographies of men from the War of Independence; some of them worked with Rosas later but those details were carefully omitted.[15]

The first major attempt to study Rosas and the Confederation as a historical period was done by Adolfo Saldías. Saldías was initially Unitarian and Anti-rosist as most of his faction's peers, and even opposed the celebration of a requiem for the death of Rosas abroad. Saldías checked all the available documentation in Buenos Aires, and visited Rosas' daughter Manuela Rosas in Southampton to check as well the archive of state documents that Rosas took with himself to the exile. The result was "Historia de la Confederación Argentina", which was rejected by Mitre because it did not "respect the noble hate" to Rosas; Saldías replied that he only attempted to be loyal to historical truth.[16]

The Generation of '80

The years between 1880 and 1930 saw a rise of positivist essayists.[17] They modified the approach in the study of history, but with little changes to general interpretations; for instance, the Great Man theory was gradually dismissed, favoring instead perspectives that explained history through social, mental, cultural or economic factors.[18] José María Ramos Mejía tried to explain key biographies, specially Rosas', through a phrenologist analysis.[19] Vicente Fidel López and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento praised his original approach, but López pointed out the lack of clinical records from the period being studied, and Sarmiento that Mejía trusted too much on libelles from that time (even by Sarmiento himself) which were more concerned with the political conflicts than with historical accuracy.[20]

Another author from this period was Ernesto Quesada, who worked with Rosas and wrote "La época de Rosas" (Spanish: The age of Rosas). Quesada considered that the events of the civil war were best explained by characteristics of Argentine society rather than by Rosas' own personality, and compared the rise of Rosas after the anarchy of the year XX with the rule of the king Louis XI of France.[21] His book was well documented, and detailed how the image of Rosas was distorted after his exile, and many key documents concealed or destroyed.[22] However, he was critical of Saldías' work, and had disputes with him.[23]

A common assumption of the time considered that Argentina began an age of prosperity after the defeats of Rosas and Urquiza at Caseros and Pavón. This perspective was weakened after the 1912 Grito de Alcorta and the raise of Hipólito Yrigoyen to the presidency. Juan Álvarez, influenced by the new state of affairs, wrote a history of Argentina from an economic perspective, and redeemed the protectionist policy of Rosas as an attempt to restore the economy of the country that had been badly damaged by wars and free trade.[24]

The new historical school

The new historical school was a new generation of historians, influenced by the University Revolution, who sought to modernize the historiographical work with new methodologies. The New Historical School did not share common ideas about historical topics in themselves, but rather a common modus operandi.[25] They were not part of the social upper classes that ruled Argentina since 1852, but sons of immigrants who arrived to Argentina during the great immigrations waves at the turn of the century. As a result, they were less influenced by factionalism and preconceived ideas.[26]

One of the authors of the New Historical School that worked with Rosas was Emilio Ravignani, his main interest being the origins of federalism and the national organization. He presided the "Institute of historical investigations", and joined the Junta of History and Numismatics by recommendation of Ricardo Levene. As subsecretary of international relations during the administration of Hipólito Yrigoyen he could check a lot of documents and bibliography, which allowed him to write a book about the first meeting of Rosas and Southern.[27] In his study of the Argentine Constitution of 1853, he considered that the Federal Pact was a strong precedent which established Federal rule, later confirmed in 1853. Unlike the authors that dismissed the period as anarchic, Ravignani considered that the pacts and the role of the caudillos was instrumental to maintain national unity. Ravignani gave new significance to the caudillos, Rosas and Artigas, his work was influenced by Saldías and Quesada.[28] His work was discussed by Ricardo Levene, who thought that the civil war and the delegation of the sum of public power generated a dictatorship, and that Rosas was a special caudillo, unlike the others.[29]

A notable historian of the 1920s was Dardo Corvalán. All his works reinvidicated the actions of Rosas. He employed a less scholarly language than Saldías or Quesada, favoring instead a language closer to the average reader,although Saldías was almost exclusively the source of his work. He did not focus his criticism on other historians, but on writers of poetry or pamphlets against Rosas, such as Rivera Indarte. Though he was an Yrigoyenist, he did not portrait Rosas as a popular or populist leader, pointing instead to his support among the wealthy people.[30]

Another important historian was Carlos Ibarguren, minister of Roque Sáenz Peña and teacher of History of Argentina at the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature. He gave a number of conferences about Rosas, which were compiled and published in a book with high success. High interest in Rosas existed for political reasons: politicians opposing Hipólito Yrigoyen (the president at the time) compared him with Rosas under a negative light, and his supporters took pride of the comparison by pointing similarities between Rosas and Yrigoyen. Ibarguren is neither critical nor supportive of Rosas, trying to provide explanations for his actions based on psychology.[31]

Historical revisionism

The 1930s saw the work of the first revisionist historians in Argentina. The historiography of Argentina is usually simplified as having a liberal or "official" history, that would be hegemonic, scientific and endorsed by the formal institutions, and a "counter history" closer to the writing of essays than to historical work and influenced by political movements. However, the context is much more complicated than that, and the frontiers between both types of history are rather diffuse. Authors deemed as "liberal" did not always follow scientific procedures, nor had homogeneous perspectives in all topics. It was not always hegemonic either, and several revisionists hold public offices or were supported by the current governments.[32] Moreover, revisionist historians did not even have homogeneous points of view: Saldías is commonly considered the first revisionist, but his work praised Bernardino Rivadavia as well as Rosas, suggesting a continuity between both, whereas most revisionists would praise Rosas and reject Rivadavia.[33]

The starting point of the historical revisionism in the 1930s is disputed, according to the perspective held over such revisionism. Authors that consider revisionism a phenomenon related to ongoing political movements point to the 1934 book La Argentina y el imperialismo británico (Spanish: Argentina and the British imperialism), by the Irazusta brothers.[34] This work, highly critical of the recent Roca–Runciman Treaty, considered that Britain had been imperialistic towards Argentina since its beginnings.[35] Authors that focus instead on the historiographical merits of revisionism choose instead Ensayo sobre el año 20 (Spanish: Essay about the Year 20) and Ensayo sobre Rosas y la suma del poder (Spanish: Essay about Rosas and the sum of power), by Julio Irazusta, also from 1934.[36] The first essay analyzed the anarchy of the year XX, and the second the historiography of Rosas. Irazusta diverged with previous works supporting Rosas: unlike Saldías, he did not consider Rosas and Rivadavia as part of a same political project but part of divergent ones. Quesada did not thought Rosas to be a skilled politician, while Irazusta did think so. Neither Saldías nor Quesada considered the battle of Caseros a turning point in the history of Argentina, while Irazusta considered it a lost chance to become a global power.[37]

There were many works about Rosas written at the end of the 1930 decade and beginning of the 1940s: Vida de Juan Manuel de Rosas (Spanish: Life of Juan Manuel de Rosas) by Manuel Gálvez in 1940, the first volume of Vida política de Juan Manuel de Rosas a través de su correspondencia (Spanish: Political life of Juan Manuel de Rosas though his correspondence) by Julio Irazusta in 1941, and Defensa y pérdida de nuestra independencia económica (Spanish: Defense and loss of our economic independence) by José María Rosa in 1942. The studies about Rosas were channeled through a new institute, the Juan Manuel de Rosas national institute of historical investigations, established in 1938. This institute and similar ones thought that public instruction was instrumental in generating a new nationalist sentiment in the population, but using new historical structures in place of the ones used in previous decades.[38]

Popular interest in Rosas further increased with the start of the Spanish Civil War and World War II, which increased and radicalized the disputes between supporters of fascism and anti-fascism to its highest level in Latin America. Most historians tried to avoid the modern political controversies and stay focused on the time period under study; Emilio Ravignani warned in 1939 that the figure of Rosas should not be used to justify modern dictatorships. Still, those disputes influenced the way people perceived history. Academics as Diego Luis Molinari and José María Rosa were attacked by student unions that considered them Nazis because of their support to Rosas, and tried to prevent them from teaching at universities.[39] Many authors, on the other hand, opted instead to avoid Rosas altogether.[40]

The Rosas National Institute quickly abandoned its historiographical purposes, and focused instead in merely promoting Rosas' image. It was considered that historical revisionism had already prevailed and that Rosas should be considered a national hero. Thus, the institute made little work in creating archives of the time period (although that was one of its initial purposes) and actual historical investigation, and worked instead with conferences, parades and literary comment.[41] Although they were accused of holding fascist ideas, they did not support Francisco Franco or other modern fascist governments, supporting instead Argentine neutrality in World War II.[42]

Palacio thought that historiography should be a reflection of the values of the society that generates it, so the historiography of decades ago was correct for its own time period but outdated in the 1930s.[43] Manuel Gálvez compared the actions of Rosas with those of other world leaders under similar circumstances, such as Louis XI of France, Diego Portales, and considered him a leader of Republicanism in Argentina, unlike the monarchist Unitarians.[44] Irazusta considered instead that Rosas was a great historical figure, not only in Argentina or even in South America, but in world history as well.[45] José María Rosa rejected the Great Man theory, and thought that history should not focus on specific isolated men or events but on the evolution of society as a whole.[46]

Peronism

The Revolution of '43 benefited revisionist historians. National universities were intervened and revisionism got a prominent role in them. However, the radical role of Jordán Bruno Genta at the National University of the Littoral was highly criticized, both by antifacists and by other revisionists as Arturo Jauretche and the Irazusta brothers. Jauretche was imprisoned for his criticism, and the magazine run by the Irazusta was closed. Others as Vicente Sierra tried a more integrationist approach.[47] The historical revisionism lost the high hierarchical roles achieved in the Revolution of '43 when Juan Perón was elected president. Revisionists had divided opinions towards him: Manuél Gálvez, Vicente Sierra, Ramón Doll and Ernesto Palacio gave their full support to Peronism; Juan Pablo Oliver and Federico Ibarguren supported him from other political parties; José María Rosa and Raúl Scalabrini Ortiz supported him at a mere personal level, without getting involved in politics, but Genta and the Irazusta brothers became antiperonists. Peronism avoided taking sides in the ideological disputes of the times, and did the same in historical topics, without endorsing nor rejecting revisionism. On the other hand, antiperonism condemned revisionism and Rosas, extrapolating in him the criticism towards Perón. Most notably, they celebrated the centennial of the battle of Caseros in which Rosas was ousted from power.[48]

The analogies between Perón and Rosas became explicit during the Revolución Libertadora, a coup that ousted Perón from power and banned Peronism. Eduardo Lonardi, de facto president, used the quote "ni vencedores ni vencidos" (Spanish: "neither victors nor vanquished"), which was used by Urquiza after deposing Rosas in Caseros. The official perspective was that Perón was "the second tyranny", the first one being Rosas, and that both ones should be equally rejected, and conversely both governments that ousted them should be praised. This perspective was condensed into the line of historical continuity "May - Caseros - Libertadora". According to it, the purpose of the May Revolution was to build government institutions, and that purpose would only be achieved after Rosas' defeat.[49][50]

This approach backfired. So far revisionism had success in academic contexts, but failed to change the popular perception of history. Perón was highly popular and the military coup unpopular; this made revisionism popular by embracing the comparison established between Rosas and Perón, but viewing him with a positive light instead. The strategy, however, was not immediate. José María Rosa was one of the most benefited revisionist historians in this context.[51]

According to the historian Félix Luna, the disputes between supporters and detractors of Rosas are outdated, and modern historiography has incorporated the several corrections made by historical revisionism.[1] Luna points that Rosas is no longer seen as a horrible monster, but as a common historical man as the others; and that it is anachronistic to judge him under modern moral standards.[1] Horacio González, head of the National Library of the Argentine Republic, points a paradigm shift in the historiography of Argentina, where revisionism has moved from being the second most important perspective into being the mainstream one.[52] However, divulgative historians often repeat outdated misconceptions about Rosas. This is usually the case of historians from outside of Argentina, who have no bias towards the Argentine topics but unwittingly repeat cliches that have long been refuted by Argentine historiography.[53]

Unitarian bias

The first historians of Argentina, such as Bartolomé Mitre, were part of the Unitarian Party in the Argentine Civil War, which was still ongoing. Thus, they wrote about themselves in a positive light, and about Federals in a negative one. They abscribed as well the "Civilization and Barbarism" perspective, deeming Rosas and all caudillos as barbarians. For this purpose, they declined the usual rules of academic historiography, bending them in order to advance a predefined inference.[54] They declined to follow the scientific method as well, highlighting and omitting information according to the effect it would have on keeping the image of Rosas as a dictator.[55]

A common way to introduce the anti-rosist bias was to describe the cruelty of things done by federals with high detail, even if unsubstantiated or based on known libels. The Unitarian violence, on the other hand, was concealed or mentioned in passing-by comments; this is the case of the persecution of Federals after the coup of Lavalle against Dorrego, or the brutal campaigns of Bartolomé Mitre against the provinces in the north between 1862 and 1865. With this method, the reader undertood that Rosas was the only violent figure of the civil war.

The magnitude of the military conflicts was usually downplayed as well, as several actions that are common during a state of war may be condemnable during peace times. Argentina faced multiple military conflicts from 1831 to 1852, both national and international, almost uninterrupted.[56] Those military threats were usually minimized by the unitarians.[57] They also omitted that José de San Martín, national hero of Argentina, supported Rosas, had many mails with him and bequeated him his curved saber.

The details that may seem favourable to Rosas were usually omitted as well, such as his integrity or his attitude after Caseros. The usual traits that consecrate national heros are the establishment of states, the recovery of territories seized by foreign powers, the consolidation of the local nationality in a land subject to other's ambitions, the vindication of national honour, and other actions that strengthen the country.[58] Unitarian history, however, condemned Rosas for actions that consecrate other national heroes in similar circumstances.[58]

Common disputes

Authoritarianism

Rosas was appointed governor in 1835 with the sum of public power, that is, the three powers delegated into the executive power. Unitarians as Domingo Faustino Sarmiento considered that Rosas became a dictator, federals as José de San Martín considered instead that, in the wake of the civil wars, this was needed to maintain social order.

His power, however, was not absolute. He still had a term of office of 5 years, being reelected at the end of each one. He did not took the power by an illegal way, such as a coup d'état, but by an appointment of the legislature, and no law prevented the legislature from doing what it did. His rule was confirmed by a popular vote, which allowed universal suffrage, and he was supported by 9,720 votes against 8. He did not actually use the full extent of the sum of public power as defined in theory: the legislative and judiciary powers were kept, and the executive power was no longer the highest court of appeal of the judiciary.

Personal wealth

Rosas was accused of embezzlement during his rule, and of taking fortunes with him when he left the country. However, as a successful landowner, he had an important wealth long before being active in politics.[59] He lived in a complete poverty during his exile in Southampton.

Being a rancher himself, Rosas defended the economic interests of the ranchers. His desire to prevent anarchy, revolutions or social commotions was shared by all ranchers. However, when he became governor he did not represent exclusively the interests of the ranchers, but those of the several factions, provinces and social groups in the Confederation. The ranchers opposed him during the rebellion of the Freemen of the South.[60]

National economy

The economy of the Argentine confederation suffered from deficits and shortages. Raúl Presbisch attributed it to a poor management,[61] and John Lynch and James Scobie to the ambitions of the landowners.[62] However, Rosas had a reputation of maintaining a strict order in the public finances among his contemporaries (with the sole exception of Mitre), and several historians and economists such as José Terry, Elena Bonura, Osvaldo Barsky and Julio Djenderedjian.[63] The civil and international wars (which included naval blockades that lasted for years) and the malones had a negative and conditioning impact on the economy, which is overlooked by the first historians mentioned.[64]

Emigration

Rosas is usually blamed as the reason why several unitarians left Argentina and settled in other countries. However, the first group left the country in early 1829: Bernardino Rivadavia, Julián Segundo de Agüero, Salvador María del Carril, Juan Cruz Varela and Florencio Varela, who promoted the ill-fated coup of Juan Lavalle. Rosas became governor in December 1829. Others like Domingo Faustino Sarmiento and Dalmasio Vélez Sarsfield are described as exiles, but they left the country on their own will, without being forced to do so.[65]

Education and culture

Public education was diminished during the government of Rosas, and the University of Buenos Aires was closed. However, the reports of Jorge Ramallo and Carlos Newland proved that this was the result of the economic crisis generated by the wars and the naval blockades, and not a politically motivated action.[65] John Lynch points that education was harmed, but not abolished.[65] Similarly, the library of Marcos Sastre that housed the members of the 1837 generation was not closed by political reasons but because of the bankruptcy of its owner. Sastre returned to the country in 1849, to the province of Santa Fe, and swore allegiance to the federal governor Pascual Echagüe.[66] The unitarian José Rivera Indarte claimed that he was expelled from the university because of his political ideas, but Dardo Corvalán Mendilaharsu proved that he was expelled because of misconduct within the university.[66]

Theaters continued working during the government of Rosas, plays were limited at times of close military threats but not abolished completely. Some English plays had poor translations to Spanish, but this was common during the time period, regardless of governors.[66]

As for Rosas himself, Julio Irazusta and Enrique Barba pointed that his letters showed a good style and grammar, unlike the illiteracy commonly attributed to the caudillos. Fermín Chávez pointed that Rosas had books of Quevedo, Horacio and Virgilio. Antirosist Alejandro Magariños Cervantes pointed that Rosas could not have stayed in power for twenty years and successfully stand against several military campaigns if he had limited intelligence.[67]

Constitutionalism

Rosas did not convene a constituent assembly to write a constitution, despite of the requests to do so. Facundo Quiroga requested so in 1834, and Rosas sent him the letter of the hacienda of Figueroa: he thought that several reasons made such a move unadvisable. Justo José de Urquiza mutinied against Rosas with the same request, deposed him in the battle of Caseros and sanctioned the Constitution of Argentina of 1853. Later historians would discuss the convenience of the sanction of a constitution at that point of history.[citation needed]

Arturo Sampay deplored in his book "The politic ideas of Rosas" (Spanish: Las ideas políticas de Rosas) that Rosas did not follow the steps of the American Revolution. However, the contexts are not comparable, as the United States did not face international aggressions after the American Revolutionary War, as the other European powers supported the weakening of the British Empire.[68]

José Luis Romero agreed in an interview with Félix Luna the validity of the points mentioned in Rosas' letter to Quiroga, and conceded that later events proved him right.[69] Arturo Jauretche pointed that Rosas wanted that the provinces achieved order first, and then the Confederation as a whole, instead of simply imposing a constitution by force. Jauretche thought that the success of the 1853 constitution is actually the result of the years that Argentina worked as a Confederation under Rosas.[70]

Footnotes

- ^ Spanish: Rosas, señor, ese tirano, ese bárbaro, así bárbaro y cruel, no era considerado lo mismo por las naciones europeas y civilizadas, y ese juicio de las naciones europeas y civilizadas, pasando a la posteridad, pondrá en duda, cuando menos, esa tiranía bárbara y execrable que Rosas ejerció entre nosotros. Es necesario, pues, marcar con una sanción legislativa declarándole reo de lesa patria para que siquiera quede marcado este punto en la historia, y se vea que el tribunal más potente, que es el tribunal popular, que es la voz del pueblo soberano por nosotros representado, lanza al monstruo el anatema llamándole traidor y reo de lesa patria... Juicios como éstos no deben dejarse a la historia... ¿Qué se dirá, qué se podrá decir en la historia cuando se viere que las naciones civilizadas del mundo, para quien nosotros somos un punto... han reconocido en ese tirano un ser digno de tratar con ellos?, ¿que la Inglaterra le ha devuelto sus cañones tomados en acción de guerra, y saludado su pabellón sangriento y manchado con sangre inocente con la salva de 21 cañonazos?... Este hecho conocido en la historia, sería un gran contrapeso, señor, si dejamos a Rosas sin este fallo. La Francia misma, que inició la cruzada en que figuraba el general Lavalle, a su tiempo también lo abandonó, trató con Rosas y saludó su pabellón con 21 cañonazos... Yo pregunto, señor, si este hecho no borrará en la historia todo lo que podamos decir, si dejamos sin un fallo a este monstruo que nos ha diezmado por tantos años... No se puede librar el juicio de Rosas a la historia, como quieren algunos... Es evidente que no puede librarse a la historia el fallo del tirano Rosas... ¡Lancemos sobre Rosas este anatema, que tal vez sea el único que puede hacerle mal en la historia, porque de otro modo ha de ser dudosa siempre su tiranía y también sus crímenes... ¿Qué se dirá en la historia, señor?, y esto sí que es hasta triste decirlo, ¿qué se dirá en la historia cuando se diga que el valiente general Brown, el héroe de la marina en la guerra de la independencia, era el almirante que defendió los derechos de Rosas? ¿Qué se dirá en la historia sin este anatema, cuando se diga que este hombre que contribuyó con sus glorias y talentos a dar brillo a ese sol de Mayo, que el señor diputado recordaba en su discurso, cuando se diga que el general San Martín, el vencedor de los Andes, el padre de las glorias argentinas, le hizo el homenaje más grandioso que puede hacer un militar legándole su espada? ¿Se creerá esto, señor, si no lanzamos un anatema contra el tirano Rosas? ¿Se creerá dentro de 20 años o de 50, si se quiere ir más lejos, a ese hombre tal como es, cuando se sepa que Brown y San Martín le servían fieles y le rendían los homenajes más respetuosos a la par de la Francia y de la Inglaterra? No, señor: dirán, los salvajes unitarios, sus enemigos, mentían. No ha sido un tirano: lejos de eso ha sido un gran hombre, un gran general. Es preciso lanzar sin duda ninguna ese anatema sobre el monstruo... ¡Ojalá hubiéramos imitado al pueblo inglés que arrastró por las calles de Londres el cadáver de Cromwell, y hubiéramos arrastrado a Rosas por las calles de Buenos Aires!... Yo he de estar, señor Presidente, por el proyecto. Si el juicio de Rosas lo librásemos al fallo de la historia, no conseguiremos que Rosas sea condenado como tirano, y sí tal vez que fuese en ella el más grande y el más glorioso de los argentinos.

References

- ^ a b c Félix Luna, "Con Rosas o contra Rosas", pp. 5–7

- ^ Devoto, pp. 18–19

- ^ Rosa, pp. 135–42

- ^ Lascano, pp. 96-97

- ^ Rosa, pp. 214–17

- ^ Ezcurra, pp. 19-21

- ^ Gelman, p. 130

- ^ Lascano, p. 108

- ^ Rosa, p. 491

- ^ Gálvez, pp. 519–20

- ^ Gálvez, pp. 535–37

- ^ Lascano, p. 41

- ^ Lascano, p. 42

- ^ Galasso, p. 583

- ^ Shumway, p. 211

- ^ Castagnino, pp. 8–9

- ^ Devoto, pp.73–75

- ^ Devoto, p. 76

- ^ Devoto, p. 82

- ^ Devoto, pp. 82–83

- ^ Devoto, p. 95

- ^ Devoto, pp. 94–95

- ^ Devoto, p. 94

- ^ Devoto, pp. 130–31

- ^ Devoto, pp. 140–41

- ^ Devoto, pp. 147–48

- ^ Devoto, p. 158–59

- ^ Devoto pp. 167–69

- ^ Devoto, pp. 178–79

- ^ Devoto, pp. 211–13

- ^ Devoto, pp. 215–16

- ^ Devoto, pp. 201–03

- ^ Devoto, pp. 203–04

- ^ Devoto, pp. 222–23

- ^ Devoto, pp. 223–24

- ^ Devoto, p. 223

- ^ Devoto, pp. 227–28

- ^ Devoto, p. 237

- ^ Devoto, pp. 238–39

- ^ Devoto, p. 240

- ^ Devoto, pp. 240–41

- ^ Devoto, p. 242

- ^ Devoto, p. 246

- ^ Devoto, pp. 248–49

- ^ Devoto, p. 253

- ^ Devoto, p. 256

- ^ Devoto, pp. 265–68

- ^ Devoto, pp. 268–70

- ^ Arturo Jauretche, "Con Rosas o contra Rosas", p. 11

- ^ Benjamín Villegas Basavilbaso, "Con Rosas o contra Rosas", p. 34

- ^ Devoto, pp. 278–81

- ^ Horacio González (23 November 2010). "La batalla de Obligado" (in Spanish). Página 12. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Lascano, pp. 46-47

- ^ Lascano, p. 28

- ^ Lascano, pp. 60-61

- ^ Lascano, p. 34

- ^ Lascano, p. 37

- ^ a b Lascano, p. 30

- ^ Lascano, pp. 24-25

- ^ Arturo Jauretche, "Con Rosas o contra Rosas", pp. 18-20

- ^ Lascano, p. 49

- ^ Lascano, p. 52

- ^ Lascano, pp. 48-53

- ^ Lascano, pp. 52-53

- ^ a b c Lascano, p. 35

- ^ a b c Lascano, p. 36

- ^ Lascano, pp. 69-70

- ^ Lascano, pp. 55-56

- ^ Lascano, p. 55

- ^ Arturo Jauretche, "Con Rosas o contra Rosas", pp. 17-18

Bibliography

- Castagnino, Leonardo (2009). Sombras y verdades (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Ediciones Fabro. ISBN 978-987-24679-8-2.

- Ezcurra, Ricardo Font (1943). San Martín y Rosas: su correspondencia (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Editorial La Mazorca.

- Gelman, Jorge (2010). Doscientos años pensando la Revolución de Mayo (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Sudamericana. ISBN 978-950-07-3179-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Devoto, Fernando (2009). Historia de la Historiografía Argentina (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Sudamericana. ISBN 978-950-07-3076-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Galasso, Norberto (2009). Seamos libres y lo demás no importa nada (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Colihue. ISBN 978-950-581-779-5.

- Gálvez, Manuel (2007). Vida de Juan Manuel de Rosas (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Editorial Claridad. ISBN 978-950-620-208-8.

- Lascano, Marcelo (2005). Imposturas históricas e identidad nacional (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: El Ateneo. ISBN 950-02-5900-1.

- Rosa, José María (1974) [1970]. Historia Argentina (in Spanish). Vol. V. Buenos Aires: Editorial Oriente S.A.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Shumway, Nicolas (1991). The Invention of Argentina. United States: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08284-2.

- Félix Luna, Arturo Jauretche, Benjamín Villegas Basavilbaso, Jaime Gálvez, León Rebollo Paz, Fermín Chávez, José Antonio Ginzo, Luis Soler Cañas, Arturo Capdevilla, Julio Irazusta, Enrique de Gandia, Ernesto Palacio, Bernardo González Arrili, Emilio Ravignani, José Antonio Saldías, Arturo Orgaz, Manuel Gálvez, Diego Luis Molinari, Ricardo Font Ezcurra, Héctor Pedro Blomberg, Ramón Doll, Adolfo Mitre, Rafael Padilla Rorbón, Alberto Gerchunoff, Mariano Bosch, Ramón de Castro Ortega, Carlos Steffens Soler, Julio Donato Álvarez, Roberto de Laferrere, Justiniano de la Fuente, Federico Barbará, Ricardo Caballero (2010). Con Rosas o contra Rosas (in Spanish). Santa Fe: H. Garetto Editor. ISBN 978-987-1493-15-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)