Songhai Empire: Difference between revisions

Tag: section blanking |

Tag: Removal of interwiki link; Wikidata is live |

||

| Line 172: | Line 172: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Hello BIiiiach |

|||

* [http://www.africankingdoms.com African Kingdoms] |

|||

* [http://www.accessgambia.com/information/songhai.html Rise and Fall of the Songhai Empire] |

|||

* [http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/africa/features/storyofafrica/4chapter4.shtml The Story of Africa: Songhay] — BBC World Service |

|||

{{Mali topics}} |

|||

{{Sahelian kingdoms}} |

|||

{{Empires}} |

|||

[[Category:1591 disestablishments]] |

|||

[[Category:Songhai Empire| ]] |

|||

[[Category:Former empires]] |

|||

[[Category:Ancient peoples]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Africa]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Azawad]] |

|||

[[Category:States and territories established in the 14th century]] |

|||

[[ar:صنغاي]] |

|||

[[bm:Songai Mansamara]] |

|||

[[zh-min-nan:Songhai Tè-kok]] |

|||

[[bg:Сонгай (кралство)]] |

|||

[[ca:Imperi Songhai]] |

|||

[[cs:Songhajská říše]] |

|||

[[da:Songhai-Imperiet]] |

|||

[[de:Songhaireich]] |

|||

[[es:Imperio songhai]] |

|||

[[eu:Songhai Inperioa]] |

|||

[[fa:امپراتوری سنغای]] |

|||

[[fr:Empire songhaï]] |

|||

[[ko:송가이 제국]] |

|||

[[hr:Songajsko Carstvo]] |

|||

[[id:Kekaisaran Songhai]] |

|||

[[it:Impero Songhai]] |

|||

[[lt:Songajus]] |

|||

[[hu:Szongai Birodalom]] |

|||

[[mr:सोंघाई साम्राज्य]] |

|||

[[ja:ソンガイ帝国]] |

|||

[[no:Songhai]] |

|||

[[nn:Songhairiket]] |

|||

[[pnb:سونگھائی بادشاہت]] |

|||

[[pl:Songhaj (państwo)]] |

|||

[[pt:Império Songhai]] |

|||

[[ru:Сонгай (государство)]] |

|||

[[simple:Songhai Empire]] |

|||

[[sr:Сонгај]] |

|||

[[fi:Songhai]] |

|||

[[sv:Songhairiket]] |

|||

[[th:จักรวรรดิซองไฮ]] |

|||

[[tr:Songhay İmparatorluğu]] |

|||

[[uk:Сонгай]] |

|||

[[ur:سلطنت سونگھائی]] |

|||

[[wo:Imbraatóor gu Songaay]] |

|||

[[yo:Ilẹ̀ Ọbalúayé Sọ́ngháì]] |

|||

[[zh:桑海帝国]] |

|||

Revision as of 20:43, 12 February 2013

Songhai Empire Songhai | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1340–1591 | |||||||||||||

The Songhai Empire, (ca. 1500) | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Gao[1] | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Songhai | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Sonni; Askia | |||||||||||||

• 1468–1492 | Sonni Ali (first) | ||||||||||||

• 1588–1592 | Askia Ishaq II (last) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Songhai state emerges at Gao | c.1000 | ||||||||||||

• freedom from Mali Empire | 14th century | ||||||||||||

• Sonni Dynasty begins | 1468 | ||||||||||||

• Askiya Dynasty begins | 1493 | ||||||||||||

• Songhai Empire destroyed | 1591 | ||||||||||||

| 1592 | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1500[2] | 1,400,000 km2 (540,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| 1550[3] | 800,000 km2 (310,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Cowry (gold, salt and copper were also traded) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Songhai Empire, also known as the Songhay Empire, was a state located in western Africa. From the early 15th to the late 16th century, Songhai was one of the largest Islamic empires in history.[4] This empire bore the same name as its leading ethnic group, the Songhai. Its capital was the city of Gao, where a Songhai state had existed since the 11th century. Its base of power was on the bend of the Niger River in present day Niger and Burkina Faso.

The Songhai state has existed in one form or another for over a thousand years, if one traces its rulers from the first settlement in Gao to its semi-vassal status under the Mali Empire through its continuation in Niger as the Dendi Kingdom.

The Songhai are thought to have settled at Gao as early as 800 CE, but did not establish it as the capital until the 11th century, during the reign of Dia Kossoi. However, the Dia dynasty soon gave way to the Sonni, preceding the ascension of Sulaiman-Mar, who gained independence and hegemony over the city and was a forbear of Sonni Ali. Mar is often credited with wresting power away from the Mali Empire and gaining independence for the small Songhai kingdom at the time.

Imperial Songhai

In 1340, the Songhai took advantage of the Mali Empire's decline and successfully asserted its independence.[5] Disputes over succession weakened the Mali Empire, and many of its peripheral subjects broke away. The Songhai made Gao their capital and began an imperial expansion of their own throughout the western Sahel. And by 1420, Songhai was strong enough to exact tribute from Masina. In all, the Sonni Dynasty would count 18 kings.

Sonni Ali

The first emperor of Songhai was Sonni Ali, reigning from about 1464 to 1493. Like the Mali kings before him, Ali was a Muslim. In the late 1460s, he conquered many of the Songhai's neighboring states, including what remained of the Mali Empire. Sunni Ali quickly established himself as the empire's most formidable military strategist and conqueror.[citation needed] His empire was the largest empire that Africa has ever seen.[citation needed]

During his campaigns for expansion, Ali conquered many lands, repelling attacks from the Mossi to the south and overcoming the Dogon people to the north. He annexed Timbuktu in 1468, after Islamic leaders of the town requested his assistance in overthrowing marauding Tuaregs who had taken the city following the decline of Mali.[6] However, Ali met stark resistance after setting his eyes on the wealthy and renowned trading town of Djenné (also known as Jenne). After a persistent seven-year siege, he was able to forcefully incorporate it into his vast empire in 1473, but only after having starved its citizens into surrender.

The invasion of Sonni Ali and his forces caused harm to the city of Timbuktu, and he was described as an intolerant tyrant in many African accounts. According to the Cambridge History of Africa the Islamic historian Al-Sa'df expresses this sentiment in describing his incursion on Timbuktu:

Sunni Ali entered Banana, committed gross iniquity, burned and destroyed the town, and brutally tortured many people there. When Akilu heard of the coming of Sonni Ali, he brought a thousand camels to carry the fuqaha of Sankore and went with them to Walata..... The Godless tyrant was engaged in slaughtering those who remained in Timbuktu and humiliated them.[7]

Sonni Ali conducted a repressive policy against the scholars of Timbuktu, especially those of the Sankore region who were associated with the Tuareg. With his control of critical trade routes and cities such as Timbuktu, Sonni Ali brought great wealth to the Songhai Empire, which at its height would surpass the wealth of Mali.[citation needed]

In oral tradition, Sonni Ali is often known as a powerful politician and great military commander.[citation needed] Whatever the case may have been, his legend consists of him being a fearless conqueror who united a great empire, sparking a legacy that is still intact today.[citation needed] Under his reign, Djenné and Timbuktu were on their way to becoming great centers of learning.[citation needed]

Askia Muhammad the Great

After taking the throne Muhammad is known as Askia the Great, even though he had no real right to be the king. Not only was he not in the royal family blood line, he did not hold the sacred symbols which entitled one to become a ruler. Furthermore, he was most likely a descendant of Soninke lineage rather than Songhay, which means that by Songhay standards his family background would have not allowed him to be King. But Askia managed to bypass that law and take the throne.

He organized the territories that Sonni Ali had previously conquered and extended his power as far to the south and east. He was not as tactful as Ali in the means of the military, but he did find success in alliances. Because of these alliances he was able to capture and conquer more vastly. Unlike Ali, however, he was a devout Muslim. Askia opened religious schools, constructed mosques, and opened up his court to scholars and poets from throughout the Muslim world. He sent his children to an Islamic School and enforced Islamic practices. Yet he was tolerant of other religions and did not force Islam on his people.

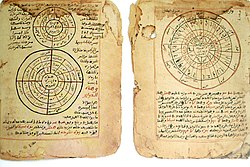

Like Mansa Musa, Askia also completed one of the five Pillars of Islam by taking a hajj to Mecca, and, also like the former, went with an overwhelming amount of gold. He donated some to charity and used the rest for lavish gifts to impress the people of Mecca with the wealth of the Songhay. Islam was so important to him that, upon his return, he recruited Muslim scholars from Egypt and Morocco to teach at the Sankore Mosque in Timbuktu as well as setting up many other learning centers throughout his empire. Among his great accomplishments was an interest in astronomical knowledge which led to a flourishing of astronomers and observatories in the capital.[8]

While not as renowned as his predecessor for his military tactics, he initiated many campaigns, notably declaring Jihad against the neighboring Mossi. Even after subduing them he did not force them to convert to Islam. His army consisted of war canoes, expert cavalry, protective armor, iron tipped weapons, and an organized militia.

Not only was he a patron of Islam, he also was gifted in administration and encouraging trade. He centralized the administration of the empire and established an efficient bureaucracy which was responsible for among other things, such as tax collection and the administration of justice. He also demanded that canals be built in order to enhance agriculture, which would eventually increase trade. More importantly than anything he did for trade was the introduction of weights and measures and the appointment of an inspector for each of Songhay's important trading centers. During his reign Islam became more widely entrenched, trans-Saharan trade flourished, and the Saharan salt mines of Taghaza were brought within the boundaries of the empire. Unfortunately, as Askia the Great grew older, his power declined. In 1528 his sons revolted against him and declared Musa, one of Askia's many sons, as king. Following Musa's overthrow in 1531, Songhay's empire went into decline. Following multiple attempts at governing the Empire by Askia's sons and grandsons there was little hope for a return to the power it once held. Between the political chaos and multiple civil wars within the empire, it came as a surprise when Morocco invaded Songhay unexpectedly. The main reason for the Moroccan invasion of Songhay was to seize control of and revive the trans-Saharan trade in gold. The Songhay military, during Askia's reign, consisted of full-time soldiers, but the king never modernized his army. The Empire fell to the Moroccans and their firearms in 1591.

Culture

At its peak, the Songhai city of Timbuktu became a thriving cultural and commercial center. Arab, Italian, and Jewish merchants all gathered for trade. A revival of Islamic scholarship also took place at the university in Timbuktu[citation needed]. However, Timbuktu was but one of a myriad of cities throughout the empire. By 1500, the Songhai Empire covered over 1.4 million square kilometers.[2][9]

Economy

Economic trade existed throughout the Empire, due to the standing army stationed in the provinces. Central to the regional economy were independent gold fields. The Julla (merchants) would form partnerships, and the state would protect these merchants and the port cities of the Niger. It was a very strong trading kingdom, known for its production of practical crafts as well as religious artifacts.

The Songhai economy was based on a clan system. The clan a person belonged to ultimately decided one's occupation. The most common were metalworkers, fishermen, and carpenters. Lower caste participants consisted of mostly non-farm working immigrants, who at times were provided special privileges and held high positions in society. At the top were noblemen and direct descendants of the original Songhai people, followed by freemen and traders. At the bottom were war captives and European slaves obligated to labor, especially in farming. James Olson describes the labor system as resembling modern day unions, with the Empire possessing craft guilds that consisted of various mechanics and artisans.[10]

Criminal justice

Criminal justice in Songhai was based mainly, if not entirely, on Islamic principles, especially during the rule of Askia Muhammad. In addition to this was the local qadis, whose responsibility was to maintain order by following Sharia law under Islamic domination, according to the Qur'an. An additional qadi was noted as a necessity in order to settle minor disputes between immigrant merchants. Kings usually did not judge a defendant; however, under special circumstances, such as acts of treason, they felt an obligation to do so and thus exert their authority. Results of a trial were announced by the "town crier" and punishment for most trivial crimes usually consisted of confiscation of merchandise or even imprisonment, since various prisons existed throughout the Empire.[11]

Qadis worked at the local level and were positioned in important trading towns, such as Timbuktu and Djenné. The Qadi was appointed by the king and dealt with common-law misdemeanors according to Sharia law. The Qadi also had the power to grant a pardon or offer refuge. The Assara-munidios, or "enforcers" worked along the lines of a police commissioner whose sole duty was to execute sentencing. Jurists were mainly composed of those representing the academic community; professors were often noted as taking administrative positions within the Empire and many aspired to be qadis.[12]

Government

Upper classes in society converted to Islam while lower classes often continued to follow traditional religions. Sermons emphasized obedience to the king. Timbuktu was the educational capital. Sonni Ali established a system of government under the royal court, later to be expanded by Askia Muhammad, which appointed governors and mayors to preside over local tributary states, situated around the Niger valley. Local chiefs were still granted authority over their respective domains as long as they did not undermine Songhai policy.[13]

Tax was imposed onto peripheral chiefdoms and provinces to ensure the dominance of Songhai, and in return these provinces were given almost complete autonomy. Songhai rulers only intervened in the affairs of these neighboring states when a situation became volatile; usually an isolated incident. Each town was represented by government officials, holding positions and responsibilities similar to today's central bureaucrats.

Under Askia Muhammad, the Empire saw increased centralization. He encouraged learning in Timbuktu by rewarding its professors with larger pensions as an incentive. He also established an order of precedence and protocol and was noted as a noble man who gave back generously to the poor. Under his policies, Muhammad brought much stability to Songhai and great attestations of this noted organization are still preserved in the works of Maghrebin writers such as Leo Africanus, among others.[citation needed]

Decline

Following the death of Emperor Askia Daoud, a civil war of succession weakened the Empire, leading Sultan Ahmad I al-Mansur of the Saadi Dynasty of Morocco to dispatch an invasion force (years earlier, armies from Portugal had attacked Morocco, and failed miserably, but the Moroccan coffers were on the verge of economic depletion and bankruptcy, as they needed to pay for the defenses used to hold off the siege) under the eunuch Judar Pasha. Judar Pasha was a Spaniard by birth, but had been captured as an infant and educated at the Saadi court. After a march across the Sahara desert, Judar's forces captured, plundered, and razed the salt mines at Taghaza and moved on to Gao. When Emperor Askia Ishaq II (r. 1588-1591) met Judar at the 1591 Battle of Tondibi, Songhai forces, despite vastly superior numbers, were routed by a cattle stampede triggered by the Saadi's gunpowder weapons.[14] Judar proceeded to sack Gao, Timbuktu and Djenné, destroying the Songhai as a regional power. Governing so vast an empire proved too much for the Saadi Dynasty, however, and they soon relinquished control of the region, letting it splinter into dozens of smaller kingdoms. The Songhai people themselves established the Dendi Kingdom.[15]

References

- ^ Bethwell A. Ogot, Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century, (UNESCO Publishing, 2000), 303.

- ^ a b hunwick 2003, pp. xlix.

- ^ Taagepera 1979, pp. 497.

- ^ http://www.africankingdoms.com African Kingdoms

- ^ Haskins, Benson & Cooper 1998, pp. 46.

- ^ Sonni ʿAlī.(2007). Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol 5: University Press, 1977, pp 421

- ^ Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, index. By Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach. pg. 764

- ^ Malio 1990.

- ^ Olson, James Stuart. The Ethnic Dimension in American History. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., 1979

- ^ Lady Lugard 1997, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Dalgleish 2005.

- ^ Iliffe 2007, pp. 72.

- ^ http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsAfrica/AfricaNiger.htm History Files

- ^ http://www.africanholocaust.net/africankingdoms.htm#songhay African Kingdoms Songhay

Sources

- Dalgleish, David (April 2005). "Pre-Colonial Criminal Justice In West Africa: Eurocentric Thought Versus Africentric Evidence" (PDF). African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies. 1 (1). Retrieved 2011-06-26.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haskins, James; Benson, Kathleen; Cooper, Floyd (1998). African Beginnings. New York City: HarperCollins. pp. 48 Pages. ISBN 0-688-10256-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Iliffe, John (2007). Africans: the history of a continent. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-68297-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hunwick, John (1988). Timbuktu & the Songhay Empire: Al-Sa'dis Ta`rikh al-sudan down to 1613 and other Contemporary Documents. Leiden: BRILL. pp. 480 pages. ISBN 90-04-12822-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lady Lugard, Flora Louisa Shaw (1997). "Songhay Under Askia the Great". A tropical dependency: an outline of the ancient history of the western Sudan with an account of the modern settlement of northern Nigeria / [Flora S. Lugard]. Black Classic Press. ISBN 0-933121-92-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Malio, Thomas A. Hale. Followed by The epic of Askia Mohammed / recounted by Nouhou (1990). Scribe, griot, and novelist : narrative interpreters of the Songhay Empire. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-0981-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taagepera, Rein (1979). Social Science History, Vol. 3, No. 3/4 "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.". Durham: Duke University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Isichei, Elizabeth. A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. Print.

- Shillington, Kevin. History of Africa . 2nd . NY: Macmillan, 2005. Print.

- Cissoko, S. M., Timbouctou et l'empire songhay, Paris 1975.

- Lange, D., Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa, Dettelbach 2004 (the book has a chapter titled "The Mande factor in Gao history", pp. 409–544).

External links

Hello BIiiiach