Epiphanius of Salamis: Difference between revisions

→Writings: adding account from newly published academic article in peer reviewed journal, removed editorial comment about him letting zeal come before facts |

adding material from newly published article in academic, peer reviewed journal, removed editorial comment on him letting his zeal get ahead of facts |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

In 399, the dispute took on another dimension, when the Bishop of Alexandria, Theophilus, who had initially supported [[John II, Bishop of Jerusalem|John]], changed his views and started persecuting Origenist monks in Egypt. As a result of this persecution, four of these monks, the so-called Tall Brothers, fled to Palestine, and then travelled to Constantinople, seeking support and spreading the controversy. [[Saint John Chrysostom|John Chrysostom, Bishop of Constantinople]] gave the monks shelter. Bishop Theophilus of Alexandria saw his chance to use this event to bring down his enemy [[Saint John Chrysostom|Chrysostom]]: in 402 he summoned a council in Constantinople, and invited those supportive of his anti-Origenist views. Epiphanius, by this time nearly 80, was one of those summoned, and began the journey to Constantinople. However, when he realized he was being used as a tool by Theophilus against Chrysostom, who had given refuge to the monks persecuted by Theophilus and who were appealing to the emperor, Epiphanius started back to Salamis, only to die on the way home in 403.<ref>Frances Young with Andrew Teal, ''From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and its Background’’, (2nd edn, 2004), pp202-3</ref> |

In 399, the dispute took on another dimension, when the Bishop of Alexandria, Theophilus, who had initially supported [[John II, Bishop of Jerusalem|John]], changed his views and started persecuting Origenist monks in Egypt. As a result of this persecution, four of these monks, the so-called Tall Brothers, fled to Palestine, and then travelled to Constantinople, seeking support and spreading the controversy. [[Saint John Chrysostom|John Chrysostom, Bishop of Constantinople]] gave the monks shelter. Bishop Theophilus of Alexandria saw his chance to use this event to bring down his enemy [[Saint John Chrysostom|Chrysostom]]: in 402 he summoned a council in Constantinople, and invited those supportive of his anti-Origenist views. Epiphanius, by this time nearly 80, was one of those summoned, and began the journey to Constantinople. However, when he realized he was being used as a tool by Theophilus against Chrysostom, who had given refuge to the monks persecuted by Theophilus and who were appealing to the emperor, Epiphanius started back to Salamis, only to die on the way home in 403.<ref>Frances Young with Andrew Teal, ''From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and its Background’’, (2nd edn, 2004), pp202-3</ref> |

||

==Iconoclasm== |

|||

Epiphanius (inter 310–320 – 403), bishop of Salamis, in Cyprus wrote, in Letter 51 (c. 394), to John, Bishop of Jerusalem about an incident of finding an image in a church in his jurisdiction: "I went in to pray, and found there a curtain hanging on the doors of the said church, dyed and embroidered. It bore an image either of Christ or of one of the saints; I do not rightly remember whose the image was. Seeing this, and being loath that an image of a man should be hung up in Christ's church contrary to the teaching of the Scriptures, I tore it asunder and advised the custodians of the place to use it as a winding sheet for some poor person." He goes on to tell John that such images are “contrary to our religion” and to instruct the presbyter of the church that such images are “an occasion of offense.”<ref>John B. Carpenter, "Icons and the Eastern Orthodox Claim to Continuity with the Early Church," ''Journal of the International Society of Christian Apologetics'', Vol. 6, No. 1, 2013, p. 118.</ref> |

|||

==Writings== |

==Writings== |

||

| Line 44: | Line 48: | ||

It lists, and refutes, 80 [[Heresy#Early Christian heresies|heresies]], some of which are not described in any other surviving documents from the time. Epiphanius begins with the 'four mothers' of pre-Christian heresy - 'barbarism', 'Scythism', 'Hellenism' and 'Judaism' - and then addresses the sixteen pre-Christian heresies that have flowed from them: four philosophical schools (Stoics, Platonists, Pythagoreans and Epicureans), and twelve Jewish sects. There then follows an interlude, telling of the Incarnation of the Word. After this, Epiphanius embarks on his account of the sixty Christian heresies, from assorted gnostics, to the various trinitarian heresies of the fourth century, closing with the Collyridians and Messalians.<ref>Andrew Louth, 'Palestine', in Frances Young, Lewis Ayres and Andrew Young, eds, ''The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature'', (2010), p286</ref> |

It lists, and refutes, 80 [[Heresy#Early Christian heresies|heresies]], some of which are not described in any other surviving documents from the time. Epiphanius begins with the 'four mothers' of pre-Christian heresy - 'barbarism', 'Scythism', 'Hellenism' and 'Judaism' - and then addresses the sixteen pre-Christian heresies that have flowed from them: four philosophical schools (Stoics, Platonists, Pythagoreans and Epicureans), and twelve Jewish sects. There then follows an interlude, telling of the Incarnation of the Word. After this, Epiphanius embarks on his account of the sixty Christian heresies, from assorted gnostics, to the various trinitarian heresies of the fourth century, closing with the Collyridians and Messalians.<ref>Andrew Louth, 'Palestine', in Frances Young, Lewis Ayres and Andrew Young, eds, ''The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature'', (2010), p286</ref> |

||

Epiphaniushe admitted on one occasion that he writes against the Origenists based only on hearsay (''Panarion'', Epiphanius 71). Nevertheless, the ''Panarion'' is a valuable source of information on the Christian church of the fourth century. It is also an important source regarding the early Jewish gospels such as the [[Gospel of the Hebrews|Gospel according to the Hebrews]] circulating among the [[Ebionites]] and the [[Nazarene (sect)|Nazarenes]], as well as the followers of [[Cerinthus]] and [[Merinthus]].<ref>Epiphanius , ''Panarion'', 30 iii 7</ref> |

|||

One unique feature of the ''Panarion'' is in the way that Epiphanius compares the various heretics to different poisonous beasts, going so far as to describe in detail the animal's characteristics, how it produces its poison, and how to protect oneself from the animal's bite or poison. For example, he describes his enemy [[Origen]] as "a toad noisy from too much moisture which keeps croaking louder and louder." He compares the [[Gnostic]]s to a particularly dreaded snake "with no pangs." The [[Ebionites]], a Christian sect that followed Jewish law, were described by Epiphanius as "a monstrosity with many shapes, who practically formed the snake-like shape of the mythical many-headed Hydra in himself." In all, Epiphanius describes fifty animals, usually one per sect.<ref name="Verheyden">{{cite journal|last=Verheyden|first=Joseph|year=2008|title=Epiphanius of Salamis on Beasts and Heretics|journal=Journal of Eastern Christian Studies|volume=60|issue=1-4|pages=143–173|url=http://secure.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article.php&id=2035279&journal_code=JECS&download=yes}}</ref> |

One unique feature of the ''Panarion'' is in the way that Epiphanius compares the various heretics to different poisonous beasts, going so far as to describe in detail the animal's characteristics, how it produces its poison, and how to protect oneself from the animal's bite or poison. For example, he describes his enemy [[Origen]] as "a toad noisy from too much moisture which keeps croaking louder and louder." He compares the [[Gnostic]]s to a particularly dreaded snake "with no pangs." The [[Ebionites]], a Christian sect that followed Jewish law, were described by Epiphanius as "a monstrosity with many shapes, who practically formed the snake-like shape of the mythical many-headed Hydra in himself." In all, Epiphanius describes fifty animals, usually one per sect.<ref name="Verheyden">{{cite journal|last=Verheyden|first=Joseph|year=2008|title=Epiphanius of Salamis on Beasts and Heretics|journal=Journal of Eastern Christian Studies|volume=60|issue=1-4|pages=143–173|url=http://secure.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article.php&id=2035279&journal_code=JECS&download=yes}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:20, 4 April 2013

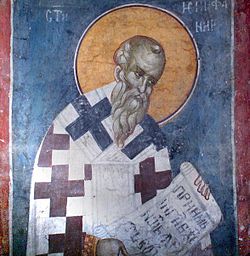

Epiphanius | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bishop of Salamis (Cyprus), Oracle of Palestine | |

| Born | ca. 310-320 Judea |

| Died | 403 at sea |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodoxy Oriental Orthodoxy Roman Catholic Church |

| Feast | May 12[1] 17 Pashons (Coptic Orthodoxy) |

| Attributes | Vested as a bishop in omophorion, sometimes holding a scroll |

Epiphanius of Salamis (inter 310–320 – 403) was bishop of Salamis, Cyprus at the end of the 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches. He gained a reputation as a strong defender of orthodoxy. He is best known for composing a very large compendium of the heresies up to his own time, full of quotations that are often the only surviving fragments of suppressed texts, and for instigating, with Tychon (Bishop of Amathus), a persecution against the non-Christians living on Cyprus, and the destruction of most of their temples.[citation needed]

Life

Epiphanius was born into a Christian family in the small settlement of Besanduk, near Eleutheropolis (modern-day Beit Guvrin, Israel),[2] and lived as a monk in Egypt, where he was educated and came into contact with Valentinian groups. He returned to Palestine around 333, when he was still a young man, and he founded a monastery at Ad nearby [3] which is often mentioned in the polemics of Jerome with Rufinus and John, Bishop of Jerusalem. He was ordained a priest, and lived and studied as superior of the monastery in Ad that he founded for thirty years and gained much skill and knowledge in that position. In that position he gained the ability to speak in several tongues including Hebrew, Syriac, Egyptian, Greek, and Latin and was called by Jerome on that account Pentaglossis ("Five tongued").[4]

His reputation for learning prompted his nomination and consecration as Bishop of Salamis, Cyprus[5] in 365 or 367, a post which he held until his death. He was also the Metropolitan of the Church of Cyprus. He served as bishop for nearly forty years, as well as traveling widely to combat unorthodox beliefs. He was present at a synod in Antioch (376) where the Trinitarian questions were debated against the heresy of Apollinarianism. He upheld the position of Bishop Paulinus, who had the support of Rome, over that of Meletius of Antioch, who was supported by the Eastern Churches. In 382 he was present at the Council of Rome, again upholding the cause of Paulinus.

Origenist controversy and death

During a visit to Palestine in 394 or 395, while preaching in Jerusalem, he attacked Origen's followers and urged the Bishop of Jerusalem, John II, to condemn his writings. He urged John to be careful of the "offense" of images in the churches. He noted that when travelling in Palestine he went into a church to pray and saw a curtain with an image of Christ or a saint which he tore down. He told Bishop John that such images were "opposed . . . to our religion."[6] This event sowed the seeds of conflict which erupted in the dispute between Rufinus and John against Jerome and Epiphanius. Epiphanius fuelled this conflict by ordaining a priest for Jerome's monastery at Bethlehem, thus trespassing on John's jurisdiction. This dispute continued during the 390s, in particular in the literary works by Rufinus and Jerome attacking one another.

In 399, the dispute took on another dimension, when the Bishop of Alexandria, Theophilus, who had initially supported John, changed his views and started persecuting Origenist monks in Egypt. As a result of this persecution, four of these monks, the so-called Tall Brothers, fled to Palestine, and then travelled to Constantinople, seeking support and spreading the controversy. John Chrysostom, Bishop of Constantinople gave the monks shelter. Bishop Theophilus of Alexandria saw his chance to use this event to bring down his enemy Chrysostom: in 402 he summoned a council in Constantinople, and invited those supportive of his anti-Origenist views. Epiphanius, by this time nearly 80, was one of those summoned, and began the journey to Constantinople. However, when he realized he was being used as a tool by Theophilus against Chrysostom, who had given refuge to the monks persecuted by Theophilus and who were appealing to the emperor, Epiphanius started back to Salamis, only to die on the way home in 403.[7]

Iconoclasm

Epiphanius (inter 310–320 – 403), bishop of Salamis, in Cyprus wrote, in Letter 51 (c. 394), to John, Bishop of Jerusalem about an incident of finding an image in a church in his jurisdiction: "I went in to pray, and found there a curtain hanging on the doors of the said church, dyed and embroidered. It bore an image either of Christ or of one of the saints; I do not rightly remember whose the image was. Seeing this, and being loath that an image of a man should be hung up in Christ's church contrary to the teaching of the Scriptures, I tore it asunder and advised the custodians of the place to use it as a winding sheet for some poor person." He goes on to tell John that such images are “contrary to our religion” and to instruct the presbyter of the church that such images are “an occasion of offense.”[8]

Writings

His earliest known work is the Ancoratus (the well anchored man), which includes arguments against Arianism and the teachings of Origen.

His best-known book is the Panarion which means "medicine-chest" (also known as Adversus Haereses, "Against Heresies"), presented as a book of antidotes for those bitten by the serpent of heresy. Written between 374 and 377, it forms a handbook for dealing with the arguments of heretics.

It lists, and refutes, 80 heresies, some of which are not described in any other surviving documents from the time. Epiphanius begins with the 'four mothers' of pre-Christian heresy - 'barbarism', 'Scythism', 'Hellenism' and 'Judaism' - and then addresses the sixteen pre-Christian heresies that have flowed from them: four philosophical schools (Stoics, Platonists, Pythagoreans and Epicureans), and twelve Jewish sects. There then follows an interlude, telling of the Incarnation of the Word. After this, Epiphanius embarks on his account of the sixty Christian heresies, from assorted gnostics, to the various trinitarian heresies of the fourth century, closing with the Collyridians and Messalians.[9]

Epiphaniushe admitted on one occasion that he writes against the Origenists based only on hearsay (Panarion, Epiphanius 71). Nevertheless, the Panarion is a valuable source of information on the Christian church of the fourth century. It is also an important source regarding the early Jewish gospels such as the Gospel according to the Hebrews circulating among the Ebionites and the Nazarenes, as well as the followers of Cerinthus and Merinthus.[10]

One unique feature of the Panarion is in the way that Epiphanius compares the various heretics to different poisonous beasts, going so far as to describe in detail the animal's characteristics, how it produces its poison, and how to protect oneself from the animal's bite or poison. For example, he describes his enemy Origen as "a toad noisy from too much moisture which keeps croaking louder and louder." He compares the Gnostics to a particularly dreaded snake "with no pangs." The Ebionites, a Christian sect that followed Jewish law, were described by Epiphanius as "a monstrosity with many shapes, who practically formed the snake-like shape of the mythical many-headed Hydra in himself." In all, Epiphanius describes fifty animals, usually one per sect.[11]

Another feature of the Panarion is the access its earlier sections provide to lost works, notably Justin Martyr's work on heresies, the Greek of Irenaeus' Against Heresies, and Hippolytus' Syntagma.[12]

The Panarion was first translated into English in 1987 and 1990.

Aside from the polemics by which he is known, Epiphanius wrote a work of biblical antiquarianism, called, for one of its sections, On Measures and Weights (περί μέτρων καί στάθμων). It was composed in Constantinople for a Persian priest, in 392,[13] and survives in Syriac and Armenian translations.[14] The first section discusses the canon of the Old Testament and its versions, the second of measures and weights, and the third, the geography of Palestine. The texts appear not to have been given a polish but consist of rough notes and sketches, as Allen A. Shaw, a modern commentator, concluded; nevertheless Epiphanius' work on metrology was important in the History of measurement.

Another work, On the Twelve Gems (De Gemmis) survives in a number of fragments, the most complete of which is the Georgian.[15]

There also exists a letter written by Epiphanius to John, Bishop of Jerusalem, in 394, preserved in Jerome's work.[16]

The collection of homilies traditionally ascribed to a "Saint Epiphanius, bishop" are dated in the late fifth or sixth century and are not connected with Epiphanius of Salamis by modern scholars.[17]

Such was Epiphanius's reputation for learning that the Physiologus, the principal source of medieval bestiaries, came to be widely falsely attributed to him.[18]

Works

- The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Book I (Sects 1-46) Frank Williams, translator, 1987 (E.J. Brill, Leiden) ISBN 90-04-07926-2

- The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Book II and III (Sects 47-80, De Fide) Frank Williams, translator, 1993 (E.J. Brill, Leiden) ISBN 90-04-09898-4

- The Panarion of St. Epiphanius, Bishop of Salamis Philip R. Amidon, translator, 1990 (Oxford University Press, New York) (This translation contains selections rather than the full work.) ISBN 0-19-506291-4

- Epiphanius' Treatise on Weights and Measures: The Syriac Version, James Elmer Dean, ed, 1935. (Chicago) [English translation of On Weights and Measures; available at http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/epiphanius_weights_03_text.htm]

Notes

- ^ Template:Gr icon Ὁ Ἅγιος Ἐπιφάνιος Ἐπίσκοπος Κωνσταντίας καὶ Ἀρχιεπίσκοπος Κύπρου. 12 Μαΐου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- ^ The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis: Book I (Sects 1-46), By Epiphanius, Epiphanius of Salamis, Translated by Frank Williams, 1987 ISBN 90-04-07926-2 p xi

- ^ The more famous Monastery of Epiphanius near Thebes, Egypt was founded by an anchorite named Epiphanius towards the end of the sixth century; it was explored by an expedition from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1912-14.

- ^ Ruf 3.6

- ^ Salamis was also known as Constantia after Constantine II.

- ^ Part 9, Letter LI. From Epiphanius, Bishop of Salamis, in Cyprus, to John, Bishop of Jerusalem (c. 394), http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3001051.htm.

- ^ Frances Young with Andrew Teal, From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and its Background’’, (2nd edn, 2004), pp202-3

- ^ John B. Carpenter, "Icons and the Eastern Orthodox Claim to Continuity with the Early Church," Journal of the International Society of Christian Apologetics, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2013, p. 118.

- ^ Andrew Louth, 'Palestine', in Frances Young, Lewis Ayres and Andrew Young, eds, The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature, (2010), p286

- ^ Epiphanius , Panarion, 30 iii 7

- ^ Verheyden, Joseph (2008). "Epiphanius of Salamis on Beasts and Heretics". Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. 60 (1–4): 143–173.

- ^ Andrew Louth, 'Palestine', in Frances Young, Lewis Ayres and Andrew Young, eds, The Cambridge History of Early Christian Literature, (2010), 286

- ^ Allen A. Shaw, "On Measures and Weights by Epiphanius" National Mathematics Magazine 11.1 (October 1936: 3-7).

- ^ English translation is Dean (1935)

- ^ Frances Young with Andrew Teal, From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and its Background’’, (2nd edn, 2004), p201

- ^ Ep 51, available at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.v.LI.html

- ^ Alvar Erikson, Sancti Epiphani Episcopi Interpretatio Evangelorum (Lund) 1938, following Dom Morin.

- ^ Frances Young with Andrew Teal, From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and its Background’’, (2nd edn, 2004), p202

External links

- St Epiphanius of Salamis Orthodox Icon and Synaxarion

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Epiphanius of Salamis". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Epiphanius of Salamis". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Epiphanius, On Biblical Weights and Measures English translation of a Syriac text

- Some excerpts from the Panarion

- (Further excerpts from the Panarion) – Currently dead.

- Letter from Epiphianus, Bishop of Salamis, in Cyprus, to John, Bishop of Jerusalem

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with analytical indexes

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Epiphanius of Salamis". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Epiphanius of Salamis". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- 4th-century births

- 403 deaths

- 4th-century Romans

- 4th-century bishops

- 4th-century Christian saints

- 5th-century Byzantine people

- Ancient Christian controversies

- Anti-Gnosticism

- Archbishops of Cyprus

- Church Fathers

- Coptic Orthodox saints

- Cypriot non-fiction writers

- Cypriot saints

- Cypriot Roman Catholic saints

- Doctors of the Church

- Eastern Orthodox saints

- Eastern Catholic saints

- Persecution by early Christians

- People who died at sea

- Roman Catholic saints from the Holy Land

- Saints from the Holy Land