Camelopardalis: Difference between revisions

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

[[NGC 2146]] is an 11th magnitude barred spiral [[starburst galaxy|starburst]] galaxy conspicuously warped by interaction with a neighbour. |

[[NGC 2146]] is an 11th magnitude barred spiral [[starburst galaxy|starburst]] galaxy conspicuously warped by interaction with a neighbour. |

||

=== Space Exploration === |

|||

The [[Space probe]] [[Voyager 1]] is moving in the direction of this constellation, though it will not be nearing any of the stars in this constellation for many thousands of years, by which time its batteries will be long dead. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 07:51, 7 May 2013

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Cam[1] |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Camelopardalis[1] |

| Pronunciation | /kəˌmɛləˈpɑːrdəl[invalid input: 'ɨ']s/, genitive the same |

| Symbolism | the Giraffe[1] |

| Right ascension | 6 |

| Declination | +70 |

| Quadrant | NQ2 |

| Area | 757 sq. deg. (18th) |

| Main stars | 2, 8 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 36 |

| Stars with planets | 4 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 0 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 3 |

| Brightest star | β Cam (4.03m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | October Camelopardalids |

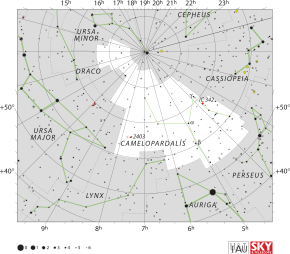

| Bordering constellations | Draco Ursa Minor Cepheus Cassiopeia Perseus Auriga Lynx Ursa Major |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −10°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of February. | |

Camelopardalis (/[invalid input: 'icon']kəˌmɛləˈpɑːrdəl[invalid input: 'ɨ']s/) is a large but faint constellation in the northern sky. The constellation was introduced in 1612 (or 1613) by Petrus Plancius. Some older astronomy books give an alternative spelling of the name, Camelopardus.[1]

Etymology

First attested in English in 1785, the word camelopardalis comes from Latin,[2] and it is the romanisation of the Greek "καμηλοπάρδαλις" meaning "giraffe",[3] from "κάμηλος" (kamēlos), "camel"[4] + "πάρδαλις" (pardalis), "leopard",[5] due to its having a long neck like a camel and spots like a leopard.

Notable features

Stars

Although Camelopardalis is the 18th largest constellation, it is not a particularly bright constellation, as the brightest stars are only of fourth magnitude. In fact, it only contains four stars above magnitude 5.0.[6]

- α Cam is a blue-hued supergiant star of magnitude 4.3, 5000 light-years from Earth. Its distance is unusual for a naked-eye star.[1]

- β Cam is the brightest star in Camelopardalis with an apparent magnitude of 4.03. This star is a double star, with components of magnitudes 4.0[7] and 8.6. The primary is a yellow-hued supergiant 1000 light-years from Earth.[1]

- 11 Cam is a star of magnitude 5.2, 650 light-years from Earth. It is very close to magnitude 6.1 12 Cam, also 650 light-years from Earth, but the two stars are not a true double star because of their separation.[1]

- Σ 1694 (Struve 1694, 32 Cam) is a binary star 300 light-years from Earth. Both components have a blue-white hue; the primary is of magnitude 5.4 and the secondary is of magnitude 5.9.[1]

- CS Cam is the second brightest star, though it has neither a Bayer nor a Flamsteed designation. It is of magnitude 4.21 and is slightly variable.[7]

Other variable stars are U Camelopardalis, VZ Camelopardalis, and Mira variables T Camelopardalis, X Camelopardalis, and R Camelopardalis.[7]

In 2011 a supernova was discovered in the constellation.[8]

Deep-sky objects

Camelopardalis is in the part of the celestial sphere facing away from the galactic plane. Accordingly, many distant galaxies are visible within its borders. NGC 2403 is a galaxy in the M81 group of galaxies, located approximately 12 million light-years from Earth[9][1] with a redshift of 0.00043. It is classified as being between an elliptical and a spiral galaxy because it has faint arms and a large central bulge. NGC 2403 was first discovered by the 18th century astronomer William Herschel, who was working in England at the time.[9] It has an integrated magnitude of 8.0 and is approximately 0.25° long.[1]

NGC 1502 is a magnitude 6.0 open cluster about 3,000 light years from Earth. It has about 45 bright members, and features a double star of magnitude 7.0 at its center. NGC 1502 is also associated with Kemble's Cascade, an small chain of stars 2.5° long that is parallel to the Milky Way and is pointed towards Cassiopeia.[1]

NGC 1501 is a planetary nebula. NGC 2655 is a small galaxy. IC 342 is one of the brightest two galaxies in the IC 342/Maffei Group of galaxies. The dwarf irregular galaxy NGC 1569 is a magnitude 11.9 starburst galaxy, about 11 million light years away.

MS0735.6+7421 is a galaxy cluster with a redshift of 0.216, located 2.6 billion light-years from Earth. It is unique for its intracluster medium, which emits x-rays at a very high rate. This galaxy cluster features two cavities 600,000 light-years in diameter, caused by its central supermassive black hole, which emits jets of matter. MS0735.6+7421 is one of the largest and most distant examples of this phenomenon.[9]

IC 166, also called Tombaugh 3, is a dim open cluster in Camelopardalis. It has an overall magnitude of 11.7 and is located 11,000 light-years from Earth. It is so faint that it has been often mistaken for a nebula in a telescope. It is a Shapley class c and Trumpler class III 1 r cluster, meaning that it is irregularly shaped and appears loose. Though it is detached from the star field, it is not concentrated at its center at all. It has more than 100 stars which do not vary widely in brightness,[10] mostly being of the 15th and 16th magnitude.[11]

NGC 2146 is an 11th magnitude barred spiral starburst galaxy conspicuously warped by interaction with a neighbour.

Space Exploration

The Space probe Voyager 1 is moving in the direction of this constellation, though it will not be nearing any of the stars in this constellation for many thousands of years, by which time its batteries will be long dead.

History

Camelopardalis was created by Petrus Plancius in 1613 to represent the animal Rebecca rode to marry Isaac in the Bible.[1] One year later, Jakob Bartsch featured it in his atlas. Johannes Hevelius gave it the official name of "Camelopardus" or "Camelopardalis" because he saw the constellation's many faint stars as the spots of a giraffe.[6]

Visualizations

This article is missing information about section. (February 2009) |

H. A. Rey has suggested an alternative way to connect the stars of Camelopardalis into a giraffe figure.

The giraffe's body consists of the quadrangle of stars α Cam, β Cam, BE Cam, and γ Cam: α Cam and β Cam being of the fourth magnitude. The stars HD 42818 (HR 2209) and M Cam form the head of the giraffe, and the stars M Cam and α Cam form the giraffe's long neck. Stars β Cam and 7 Cam form the giraffe's front leg, and variable stars BE Cam and CS Cam form the giraffe's hind leg.

Equivalents

In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Camelopardalis are located within a group of circumpolar stars called the Purple Forbidden Enclosure (紫微垣 Zǐ Wēi Yuán).

See also

- Camelopardalis (Chinese astronomy)

- IC 442, spiral galaxy

References

- Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ridpath 2001, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles. "camelopardalis". A Latin Dictionary. Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "καμηλοπάρδαλις". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "κάμηλος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "πάρδαλις". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ a b Staal 1988, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Norton 1973, pp. 118=119.

- ^ Boyle, Rebecca (3 January 2011). "10-Year-Old Canadian Girl Is The Youngest Person Ever to Discover a Supernova". Popular Science. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- ^ a b c Wilkins & Dunn 2006.

- ^ Levy 2005, p. 89.

- ^ Levy 2005, p. 91.

- References

- Levy, David H. (2005), Deep Sky Objects, Prometheus Books, ISBN 1-59102-361-0

- Norton, Arthur P. (1973), Norton's Star Atlas, pp. 118–119, ISBN 0-85248-900-5

- Rey, H. A. (1997), The Stars—A New Way To See Them, Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-24830-2

- Ridpath, Ian (2001), Stars and Planets Guide, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08913-2

- Ridpath, Ian (2007), Stars and Planets Guide, Wil Tirion (4th ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4

- Staal, Julius D.W. (1988), The New Patterns in the Sky, McDonald and Woodward Publishing Company, ISBN 0-939923-04-1

- Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006), 300 Astronomical Objects: A Visual Reference to the Universe (1st ed.), Firefly Books, ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3