Giganotosaurus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tag: Mobile edit |

Tigerhawkvok (talk | contribs) m →Description: Fixed incorrect unit conversion syntax resulting in bogus value |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

[[File:Largesttheropods.png|thumb|left|A size comparison between ''Giganotosaurus'' and other theropods]] |

[[File:Largesttheropods.png|thumb|left|A size comparison between ''Giganotosaurus'' and other theropods]] |

||

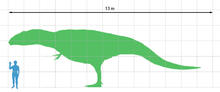

[[File:Giganotosaurus scale.png|thumb|right|Size compared with a human]] |

[[File:Giganotosaurus scale.png|thumb|right|Size compared with a human]] |

||

The shoulder blade was very short and thick, with sudden kinks in its shaft. The [[ischium]] had a paddle-shaped end; the [[femur|thigh bone]], {{convert|1.43|m|ft|abbr=on}} long in the holotype, had a head that was pointing relatively upwards.<ref>J.O. Calvo, 1999, "Dinosaurs and other vertebrates of the Lake Ezequiel Ramos Mexía area, Neuquén-Patagonia, Argentina", In: Y. Tomida, T. H. Rich, and P. Vickers-Rich (eds.), ''Proceedings of the Second Gondwanan Dinosaur Symposium, National Science Museum Monographs'' '''15''': 13-45</ref> The mid dorsal vertebrae carried rather high spines. The total length of the holotype has been estimated between {{convert|12.2 and 12.5|m|ft|abbr=on}},<ref name="Coria1995"/><ref name="coria2006">Coria, R.A. and Currie, P.J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina." ''Geodiversitas'', '''28'''(1): 71-118. [http://www.mnhn.fr/museum/front/medias/publication/7653_g06n1a4.pdf pdf link]</ref> the largest specimen is {{convert|13.2|m|ft|abbr=on}},<ref name="Holtz2008">Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) ''Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages,'' [http://www.geol.umd.edu/~tholtz/dinoappendix/HoltzappendixWinter2011.pdf Winter 2011 Appendix.]</ref> and the weight between {{convert|6.5|and|13.8|tonnes|lb|-1}}.<ref name="seebacher2001">{{cite journal | doi = 10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2 | last1 = Seebacher | first1 = F. | year = 2001 | title = A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs | url = | journal = Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology | volume = 21 | issue = 1| pages = 51–60 | issn = 0272-4634 }}</ref><ref name=TH07>{{cite journal |last=Therrien |first=F. |coauthors= and Henderson, D.M. |year=2007 |title=My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods |journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology |volume=27 |issue=1 |pages=108–115 |doi=10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2 |issn=0272-4634}}</ref> |

The shoulder blade was very short and thick, with sudden kinks in its shaft. The [[ischium]] had a paddle-shaped end; the [[femur|thigh bone]], {{convert|1.43|m|ft|abbr=on}} long in the holotype, had a head that was pointing relatively upwards.<ref>J.O. Calvo, 1999, "Dinosaurs and other vertebrates of the Lake Ezequiel Ramos Mexía area, Neuquén-Patagonia, Argentina", In: Y. Tomida, T. H. Rich, and P. Vickers-Rich (eds.), ''Proceedings of the Second Gondwanan Dinosaur Symposium, National Science Museum Monographs'' '''15''': 13-45</ref> The mid dorsal vertebrae carried rather high spines. The total length of the holotype has been estimated between {{convert|12.2| and |12.5|m|ft|abbr=on}},<ref name="Coria1995"/><ref name="coria2006">Coria, R.A. and Currie, P.J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina." ''Geodiversitas'', '''28'''(1): 71-118. [http://www.mnhn.fr/museum/front/medias/publication/7653_g06n1a4.pdf pdf link]</ref> the largest specimen is {{convert|13.2|m|ft|abbr=on}},<ref name="Holtz2008">Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) ''Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages,'' [http://www.geol.umd.edu/~tholtz/dinoappendix/HoltzappendixWinter2011.pdf Winter 2011 Appendix.]</ref> and the weight between {{convert|6.5|and|13.8|tonnes|lb|-1}}.<ref name="seebacher2001">{{cite journal | doi = 10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2 | last1 = Seebacher | first1 = F. | year = 2001 | title = A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs | url = | journal = Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology | volume = 21 | issue = 1| pages = 51–60 | issn = 0272-4634 }}</ref><ref name=TH07>{{cite journal |last=Therrien |first=F. |coauthors= and Henderson, D.M. |year=2007 |title=My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods |journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology |volume=27 |issue=1 |pages=108–115 |doi=10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2 |issn=0272-4634}}</ref> |

||

==Paleobiology== |

==Paleobiology== |

||

Revision as of 02:09, 25 November 2013

| Giganotosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Replica skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Carcharodontosauridae |

| Tribe: | †Giganotosaurini |

| Genus: | †Giganotosaurus Coria & Salgado, 1995 |

| Species: | †G. carolinii

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Giganotosaurus carolinii Coria & Salgado, 1995

| |

Giganotosaurus (/ˌdʒaɪɡəˌnoʊtəˈsɔːrəs/ JY-gə- NOH-tə-SOR-əs)[1] is a genus of carcharodontosaurid dinosaurs that lived in what is now Argentina during the early Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous Period,[2] approximately some 100 to 97 million years ago.[3] It included some of the largest known terrestrial carnivores, with known individuals equaling the size of the largest of the genera Tyrannosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus, but not as large as those of Spinosaurus.

Description

The skeleton of the holotype specimen (MUCPv-Ch1) is about 70% complete and includes parts of the skull, a lower jaw, pelvis, hindlimbs and most of the backbone, missing only the premaxillae, jugals, quadratojugals, the back of the lower jaws and the forelimbs. A second specimen (MUCPv-95) has also been identified, found in 1988 by Jorge Calvo and consisting of a fragment of a lower jaw,[4] said to be 8% larger than the corresponding part in the first specimen.[5]

The skull of Giganotosaurus is large; that of the holotype was in 1995 estimated at 1.53 m (5.0 ft) in length.[6] Even though the original authors briefly claimed the length to be up to 1.8 m (5.9 ft)[7]—leading to an estimate of 1.95 m (6.4 ft) skull length for the referred specimen[5]—this claim was not repeated by subsequent workers[8] and one of the original authors was in 2002 co-writer of an article giving a holotype skull length of 1.6 m (5.2 ft).[2] Some have claimed that even the original estimate was too long and believe the skull to be almost exactly comparable to the one of Tyrannosaurus in length.[9] The skull is slender and elongated in build, with rugose areas on the edges of the snout top and above the eye. The supratemporal openings were overhung by the edges of the skull roof where the jaw muscles of each side directly attached instead of meeting each other at a midline skull crest. The back of the skull as preserved is strongly inclined forwards, bringing the jaw joints far behind the attachment point of the neck.[2] The endocast of Giganotosaurus has a volume of 275 cc (16.8 cu in)[2] and including the olfactory bulbs, it was 19% longer than that of the related theropod, Carcharodontosaurus saharicus.[10]

The shoulder blade was very short and thick, with sudden kinks in its shaft. The ischium had a paddle-shaped end; the thigh bone, 1.43 m (4.7 ft) long in the holotype, had a head that was pointing relatively upwards.[11] The mid dorsal vertebrae carried rather high spines. The total length of the holotype has been estimated between 12.2 and 12.5 m (40 and 41 ft),[6][12] the largest specimen is 13.2 m (43 ft),[3] and the weight between 6.5 and 13.8 tonnes (14,330 and 30,420 lb).[13][14]

Paleobiology

Titanosaur fossils belonging to Andesaurus and Limaysaurus have been recovered near the remains of Giganotosaurus, leading to speculation that these carnivores may have preyed on the giant herbivores. Fossils of the related carcharodontosaurid Mapusaurus grouped closely together may indicate pack hunting, a behavior that could possibly extend to Giganotosaurus itself.

Blanco and Mazzetta (2001) estimated that for Giganotosaurus a growing imbalance when increasing its velocity would pose an upper limit of 14 metres per second (50 km/h; 31 mph) to its running speed, after which minimal stability would have been lost.[15]

In 2005 François Therrien e.a. estimated that the bite force of Giganotosaurus was three times less than that of Tyrannosaurus and that the lower jaws were optimised for inflicting slicing wounds; the point of the mandibula was reinforced to this purpose with a "chin" and broadened to handle smaller prey.[16]

Classification

Giganotosaurus, along with relatives like Tyrannotitan, Mapusaurus and Carcharodontosaurus, are members of the carnosaur family Carcharodontosauridae. Both Giganotosaurus and Mapusaurus have been placed in their own subfamily Giganotosaurinae by Coria and Currie in 2006 as more carcharodontosaurid dinosaurs are found and described, allowing interrelationships to be calculated.[12]

Discovery and species

The most complete find of Giganotosaurus was made by Rubén Dario Carolini, an amateur fossil hunter who, on 25 July 1993, discovered a skeleton in deposits of Patagonia (southern Argentina) in what is now considered the Candeleros Formation.[2] The discovery was scientifically reported in 1994.[17] The initial description was published by Rodolfo Coria and Leonardo Salgado in the journal Nature in September 1995.[6] The type species is Giganotosaurus carolinii. The generic name means "giant southern lizard", derived from the Ancient Greek gigas/γίγας meaning "giant", notos/νότος meaning "southern" and -sauros/-σαύρος meaning "lizard".[18] The specific name honours Carolini.

Paleoecology

Giganotosaurus was possibly the apex predator in its ecosystem. It shared its environment with titanosaurian sauropod Andesaurus and the rebbachisaurid sauropods Limaysaurus and Nopcsaspondylus. Iguanodont and ornithischian remains have reportedly been found there too. Large abelisaurid theropod Ekrixinatosaurus also shared the environment, and was possibly a competitor at times. Smaller predators also inhabited the area. These included dromaeosaurid Buitreraptor, alvarezsaurid Alnashetri, and basal coelurosaurian Bicentenaria. The primitive snake Najash lived here as well, along with turtles, fish, frogs, and cladotherian mammals. Pterosaurs also lived in the area.[19]

References

- ^ Academy of Natural Sciences: Giganotosaurus

- ^ a b c d e Coria, R.A. and Currie, P.J. (2002). "Braincase of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22(4): 802-811.

- ^ a b Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- ^ J.O. Calvo, 1990, "Un gigantesco theropodo del Miembro Candeleros (Albiano–Cenomaniano) del la Formación Río Limay, Patagonia, Argentina", VII Jornadas Argentinas de Paleontología de Vertebrados. Ameghiniana 26(3-4): 241

- ^ a b Calvo, J.O. and Coria, R.A. (1998) "New specimen of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Coria & Salgado, 1995), supports it as the largest theropod ever found." Gaia, 15: 117–122. pdf link

- ^ a b c Coria, R.A. & Salgado, L. (1995). A new giant carnivorous dinosaur from the Cretaceous of Patagonia. Nature 377: 225-226

- ^ Coria, R. & Salgado, L., 1996, "Dinosaurios carnívoros de Sudamérica", Investigación Sciencia, 237: 39-40

- ^ Currie, Philip J. (2000). "A new specimen of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous Antlers Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian) of Oklahoma, USA". Geodiversitas. 22 (2): 207–246.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Matthew T. Carrano, Roger B. J. Benson & Scott D. Sampson, 2012, "The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda)", Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 10(2): 233

- ^ Ariana Paulina Carabajal & J.I. Canale, 2010, "Cranial endocast of the carcharodontosaurid theropod Giganotosaurus carolinii Coria & Salgado, 1995", Neues Jahrbuch fuer Geologie & Palaeontologie, Abhandlungen 258(2): 249-256

- ^ J.O. Calvo, 1999, "Dinosaurs and other vertebrates of the Lake Ezequiel Ramos Mexía area, Neuquén-Patagonia, Argentina", In: Y. Tomida, T. H. Rich, and P. Vickers-Rich (eds.), Proceedings of the Second Gondwanan Dinosaur Symposium, National Science Museum Monographs 15: 13-45

- ^ a b Coria, R.A. and Currie, P.J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina." Geodiversitas, 28(1): 71-118. pdf link

- ^ Seebacher, F. (2001). "A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Therrien, F. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Blanco, R. Ernesto; Mazzetta, Gerardo V. (2001). "A new approach to evaluate the cursorial ability of the giant theropod Giganotosaurus carolinii". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 46 (2): 193–202.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Therrien, François; Henderson, Donald M.; Ruff, Christopher B., 2005, "Bite Me: Biomechanical models of theropod mandibles and implications for feeding". In: Carpenter, Kenneth. The Carnivorous Dinosaurs. Life of the Past. Indiana University Press. pp. 179–237

- ^ R.A. Coria and L. Sagado, 1994, "A giant theropod from the middle Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14(3, supplement):22A

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1980). Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ Leanza, H.A.; Apesteguia, S.; Novas, F.E. & de la Fuente, M.S. (2004): Cretaceous terrestrial beds from the Neuquén Basin (Argentina) and their tetrapod assemblages. Cretaceous Research 25(1): 61-87. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2003.10.005 (HTML abstract)

External links

- Giganotosaurus at DinoData.

- "What were the longest/heaviest predatory dinosaurs?" Mike Taylor. The Dinosaur FAQ. August 27, 2002.