Elizabeth Catlett: Difference between revisions

Rhinestone K (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 209.118.71.210 (talk) to last version by ClueBot NG |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Elizabeth Catlett Mora''' (April 15, 1915{{spaced ndash}} April 2, 2012<ref name=Boucher/>) was an [[United States|American]] |

'''Elizabeth Catlett Mora''' (April 15, 1915{{spaced ndash}} April 2, 2012<ref name=Boucher/>) was an [[United States|American]] (African-American) [[sculpture|sculptor]] and [[printmaker]]. Catlett is best known for the black, expressionistic sculptures and prints she produced during the 1960s and 1970s, which are seen as [[American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)|politically charged]]. |

||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

Revision as of 17:27, 29 March 2014

Elizabeth Catlett | |

|---|---|

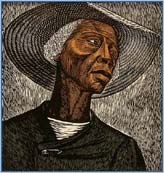

Elizabeth Catlett, 1986 (photograph by Fern Logan) | |

| Born | April 15, 1915 |

| Died | April 2, 2012 (aged 96)[1] |

| Nationality | American and Mexican |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Notable work | Students Aspire |

Elizabeth Catlett Mora (April 15, 1915 – April 2, 2012[1]) was an American (African-American) sculptor and printmaker. Catlett is best known for the black, expressionistic sculptures and prints she produced during the 1960s and 1970s, which are seen as politically charged.

Biography

Catlett was born in Washington, D.C., the youngest of three children.

She attended the Lucretia Mott Elementary School, Dunbar High School, and then Howard University where she studied design, printmaking and drawing. In an interview in December 1981 in Artist and Influence magazine, she stated that she changed her major to painting because of the influence of James A. Porter, and because there was no sculpture division at Howard at the time. She received her BS cum laude from Howard in 1935. She then worked as a high school teacher in North Carolina but left after two years, frustrated by the low teaching salaries for black people.

While living and working in Harlem, New York, she was briefly married to Charles White.

In 1947, she married Mexican artist Francisco Mora, and made Mexico her permanent home, later becoming a Mexican citizen. They have three sons, including film director Juan Mora. Her granddaughter, Naima Mora, was the Cycle 4 winner of the America's Next Top Model television show. Catlett's sculpture, Naima, is of Naima as a child.

After retiring in 1975, Catlett continued to be active in the Cuernavaca, Mexico art community.

Education

In 1940 Catlett became the first student to receive an M.F.A. in sculpture at the University of Iowa School of Art and Art History. While there, she was influenced by American landscape painter Grant Wood, who urged students to work with the subjects they knew best. For Catlett, this meant black people, and especially black women, and it was at this point that her work began to focus on African Americans. Her piece Mother and Child, done in limestone in 1939 for her thesis,[2] won first prize in sculpture at the American Negro Exposition in Chicago in 1940.

She studied ceramics at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1941, lithography at the Art Students League of New York in 1942–1943, and with sculptor Ossip Zadkine in New York in 1944.

Career

Catlett became the "promotion director" for the George Washington Carver School in Harlem located at 57 W. 125th St. Roy DeCarava was one of the students. Some of the teachers included Ernest Crichlow, Norman Lewis, and Charles White, who was for a time her husband.

In 1946, Catlett received a Rosenwald Fund Fellowship that allowed her to travel to Mexico where she studied wood carving with Jose L. Ruiz and ceramic sculpture with Francisco Zúñiga, at the Escuela de Pintura y Escultura, Esmeralda, Mexico. She later moved to Mexico, married, and became a Mexican citizen.

In Mexico, she worked with the Taller de Gráfica Popular, (People's Graphic Arts Workshop), a group of printmakers organized in 1937 by Leopoldo Méndez, Raúl Anguiano, Luis Arenal, and Pablo O'Higgins and dedicated to using their art to promote social change. There she and other artists created a series of linoleum cuts on black heroes. They "did posters, leaflets, collective booklets, illustrations for textbooks, posters and illustrations for the construction of schools, against illiteracy in Mexico."

She became the first female professor of sculpture and head of the sculpture department at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, School of Fine Arts, San Carlos, in Mexico City, in 1958, and taught there until retiring in 1975. She was active in the art community of Cuernavaca, Morelos.

In 1980 Catlett donated a collection of her personal papers, exhibition catalogs, and other documentary materials to the Archives of American Art in the Smithsonian Institution.[3]

Catlett died on April 2, 2012, in Cuernavaca. She was 96.[1]

Awards

Catlett received numerous awards including the Women's Caucus For Art. The Graphic Arts Workshop has won an international peace prize. An Elizabeth Catlett Week was proclaimed in Berkeley, California, and an Elizabeth Catlett Day in Cleveland, Ohio. She was named an honorary citizen of New Orleans and received the keys to many cities. She received an honorary Doctorate from Pace University, in New York and was accompanied to the presentation by fellow sculptor and good friend Manuel Bennett.[citation needed]

In 2003, Catlett was the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award, International Sculpture Center.[4]

In 2008, Catlett was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts by Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA.[5]

Works

Some of her best-known prints are Sharecropper (1968 or 1970) and Malcolm X Speaks for Us (1969). Well-known sculptured pieces include Dancing Figure (1961), The Black Woman Speaks and Target (1970), and The Singing Head. The National Council of Negro Women in New York City commissioned her to create a bronze sculpture, and her bronze relief adorns the Chemical Engineering Building at Howard University. Catlett's statue of Louis Armstrong was dedicated in Louis Armstrong Park, New Orleans, in 1976. In 2003 Catlett designed a memorial to author Ralph Ellison, which stands in West Harlem, NY.

The Smithsonian Art Collectors Program commissioned Catlett in 1995 to create a print to benefit the educational and cultural programs put on by the Smithsonian Associates. The resulting lithograph, Children With Flowers, highlights the unity and diversity of children, and hangs in the ongoing exhibit Graphic Eloquence in the S. Dillon Ripley Center on the National Mall in the District of Columbia.

In 2010, Cattlet finishes her 10-foot sculpture of Mahalia Jackson, the great Gospel singer. It was inaugurated in New Orleans Treme neighborhood; which isn't far from her 1975 Louis Armstrong statue.

Catlett created numerous outdoor sculptures which are displayed in Mexico; in Jackson, Mississippi; and, Washington, D.C. She is represented in many collections through the world including the Institute of Fine Arts, Mexico, the Museum of Modern Art, NY; Museum of Modern Art, Mexico; National Museum of Prague; Library of Congress, Washington, D.C; Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA; State University of Iowa; Howard University; Fisk University; Atlanta University; the Barnett-Aden Collection, Tampa, Fl.; Schomburg Collection, NY; Rothman Gallery, L.A.; Museum of New Orleans, High Museum, Atlanta; and the Metropolitan Museum, NY.

Auction records

On October 8, 2009, Swann Galleries auctioned Elizabeth Catlett’s life-size red cedar sculpture Homage to My Young Black Sisters, 1968, for $288,000—more than any previous work by the artist at auction. The prior record for a Catlett sculpture was set at Swann in February 2008 for a painted terra cotta work.

Selected works

References

- ^ a b c Boucher, Brian. "Elizabeth Catlett, 1915–2012". News & opinion. Art in America. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ^ Rubenstein, Charlotte Streifer, American Women Sculptors, G.K. Hall & Co., Boston 1990

- ^ "Elizabeth Catlett papers, 1957–1980". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ ISC website. Lifetime Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ http://www.cmu.edu/news/archive/2008/May/may15_catlettexhibition.shtml

External links

- Listings for over 70 works produced by Elizabeth Catlett during her time at the Taller de Gráfica Popular can be viewed at Gráfica Mexciana.

- Elizabeth Catlett Online ArtCyclopedia guide to pictures of works by Elizabeth Catlett in art museum sites and image archives worldwide.

- African American World . Arts & Culture . Art Focus |PBS Elizabeth Catlett page of the Social Activism section of the PBS article on African American Artists

- June Kelly Gallery Elizabeth Catlett Includes a detailed timeline of Catlett's life

- Distinguished Alumni Awards The University of Iowa Presents Elizabeth Catlett Mora

- Elizabeth Catlett's oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Form That Achieves Sympathy A Conversation with Elizabeth Catlett by Michael Brenson in Sculpture, a publication of the International Sculpture Center

- Dufrene, Phoebe (1994), "A Visit with Elizabeth Catlett", Art Education, 47 (1), National Art Education Association: 68–72, doi:10.2307/3193443, JSTOR 3193443

- Brief Profile with nice picture

- Elizabeth Catlett's oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Catlett's Children With Flowers, the Smithsonian Art Collectors Program

- Elizabeth Catlett, Sculptor With Eye on Social Issues, Is Dead at 96; New York Times; Karen Rosenberg; April 3, 2012

- 1915 births

- 2012 deaths

- Mexican sculptors

- African-Americans' civil rights activists

- American emigrants to Mexico

- American sculptors

- American printmakers

- African-American artists

- Feminist artists

- Howard University alumni

- University of Iowa alumni

- School of the Art Institute of Chicago alumni

- Artists from Washington, D.C.

- Naturalized citizens of Mexico