Thermodynamic system: Difference between revisions

m minor fixes, mostly disambig links using AWB |

→Closed system: Internal energy, U is a state property so it should be dU not del(U) |

||

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

where ''T'' is the absolute temperature and ''S'' is the entropy of the system. With these relations the fundamental thermodynamic relationship, used to compute changes in internal energy, is expressed as: |

where ''T'' is the absolute temperature and ''S'' is the entropy of the system. With these relations the fundamental thermodynamic relationship, used to compute changes in internal energy, is expressed as: |

||

:<math>{\ |

:<math>{\mathrm{d}U}=T\mathrm{d}S-P\mathrm{d}V.</math> |

||

For a simple system, with only one type of particle (atom or molecule), a closed system amounts to a constant number of particles. However, for systems undergoing a [[chemical equilibrium|chemical reaction]], there may be all sorts of molecules being generated and destroyed by the reaction process. In this case, the fact that the system is closed is expressed by stating that the total number of each elemental atom is conserved, no matter what kind of molecule it may be a part of. Mathematically: |

For a simple system, with only one type of particle (atom or molecule), a closed system amounts to a constant number of particles. However, for systems undergoing a [[chemical equilibrium|chemical reaction]], there may be all sorts of molecules being generated and destroyed by the reaction process. In this case, the fact that the system is closed is expressed by stating that the total number of each elemental atom is conserved, no matter what kind of molecule it may be a part of. Mathematically: |

||

Revision as of 19:47, 5 June 2014

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

A thermodynamic system is a precisely specified macroscopic region of the universe, defined by boundaries or walls of particular natures, together with the physical surroundings of that region, which determine processes that are allowed to affect the interior of the region, studied using the principles of thermodynamics.

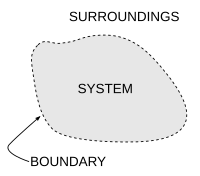

All space in the universe outside the thermodynamic system is known as the surroundings, the environment, or a reservoir. A system is separated from its surroundings by a boundary, which may be notional or real but, by convention, delimits a finite volume. Transfers of work, heat, or matter and energy between the system and the surroundings may take place across this boundary. A thermodynamic system is classified by the nature of the transfers that are allowed to occur across its boundary, or parts of its boundary.

A thermodynamic system has a characteristic set of thermodynamic parameters, or state variables. They are experimentally measurable macroscopic properties, such as volume, pressure, temperature, electric field, and others. The set of values of the thermodynamic parameters necessary to uniquely define a state of a system is called the thermodynamic state of a system. The state variables of a system are normally related by one or more functional relationships, the equations of state. In equilibrium thermodynamics, the state variables do not include fluxes, because for a state of thermodynamic equilibrium, all fluxes have zero values, by definition. Equilibrium thermodynamics allows processes which of course involve fluxes, but these must have ceased by the time a thermodynamic process or operation is complete, bringing a system to its eventual thermodynamic state. Non-equilibrium thermodynamics allows its state variables to include non-zero fluxes, that describe transfers of matter or energy or entropy between a system and its surroundings.[1]

An isolated system is an idealized system that has no interaction with its surroundings. It is not customary to ask how is its state detected empirically. Ideally it is in its own internal thermodynamic equilibrium when its state does not change with time.

A system that is not isolated can be in thermodynamic equilibrium with its surroundings, according to the characters of the separating walls. Or it can be in a state constant or precisely cyclically changing in time - a steady state - that is far from equilibrium. Or it can be in a changing state that is not in thermodynamic equilibrium. Classical thermodynamics considers only states of thermodynamic equilibrium or states constant or precisely cycling in time. An interaction of system and surroundings can be by contact, for example allowing conduction of heat, or by long-range forces, such as an electric field established and maintained by the surroundings.

A thermodynamic system is a specialized conception, which does not cover all physical systems. A physical system is a far broader conception, beyond the scope of the present article. The physical existence of thermodynamic systems as strictly defined here may be considered a fundamental postulate of equilibrium thermodynamics, although such is usually not listed as a numbered law of thermodynamics.[2][3] According to Bailyn, the commonly rehearsed statement of the zeroth law of thermodynamics is a consequence of this fundamental postulate.[4]

Originally, in 1824, Sadi Carnot described a thermodynamic system as the working substance of a heat engine under study.

| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

Overview

Thermodynamics describes the macroscopic physics of matter and energy, especially including heat transfer, using the concept of the thermodynamic system, a region of the universe that is under study, specified by thermodynamic state variables, together with the kinds of transfer that may occur between it and its surroundings, as determined by the physical properties of the walls of the system.

|

Isolated systems are completely isolated from their environment. They do not exchange energy or matter with their environment. In practice, a system can never be absolutely isolated from its environment, because there is always at least some slight coupling, such as gravitational attraction.

Closed systems are able to exchange energy (heat and work) but not matter with their environment. A greenhouse is an example of a closed system exchanging heat but not work with its environment. Whether a system exchanges heat, work or both is usually thought of as a property of its boundary.

An open system has a part of its boundary that allows transfer of energy as well as matter between it and its surroundings. A boundary part that allows matter transfer is called permeable.

An example system is the system of hot liquid water and solid table salt in a sealed, insulated test tube held in a vacuum (the surroundings). The test tube constantly loses heat in the form of black-body radiation, but the heat loss progresses very slowly. If there is another process going on in the test tube, for example the dissolution of the salt crystals, it probably occurs so quickly that any heat lost to the test tube during that time can be neglected. Thermodynamics in general does not measure time, but it does sometimes accept limitations on the time frame of a process.

History

The first to develop the concept of a thermodynamic system was the French physicist Sadi Carnot whose 1824 Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire studied what he called the working substance, e.g., typically a body of water vapor, in steam engines, in regards to the system's ability to do work when heat is applied to it. The working substance could be put in contact with either a heat reservoir (a boiler), a cold reservoir (a stream of cold water), or a piston (to which the working body could do work by pushing on it). In 1850, the German physicist Rudolf Clausius generalized this picture to include the concept of the surroundings, and began referring to the system as a "working body." In his 1850 manuscript On the Motive Power of Fire, Clausius wrote:

"With every change of volume (to the working body) a certain amount work must be done by the gas or upon it, since by its expansion it overcomes an external pressure, and since its compression can be brought about only by an exertion of external pressure. To this excess of work done by the gas or upon it there must correspond, by our principle, a proportional excess of heat consumed or produced, and the gas cannot give up to the "surrounding medium" the same amount of heat as it receives."

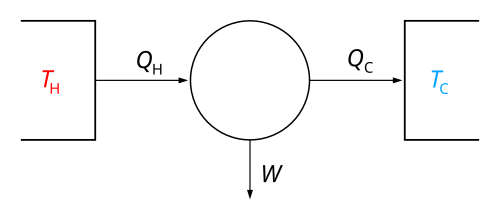

The article Carnot heat engine shows the original piston-and-cylinder diagram used by Carnot in discussing his ideal engine; below, we see the Carnot engine as is typically modeled in current use:

In the diagram shown, the "working body" (system), a term introduced by Clausius in 1850, can be any fluid or vapor body through which heat Q can be introduced or transmitted through to produce work. In 1824, Sadi Carnot, in his famous paper Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire, had postulated that the fluid body could be any substance capable of expansion, such as vapor of water, vapor of alcohol, vapor of mercury, a permanent gas, or air, etc. Though, in these early years, engines came in a number of configurations, typically QH was supplied by a boiler, wherein water boiled over a furnace; QC was typically a stream of cold flowing water in the form of a condenser located on a separate part of the engine. The output work W was the movement of the piston as it turned a crank-arm, which typically turned a pulley to lift water out of flooded salt mines. Carnot defined work as "weight lifted through a height."

Boundary

A system boundary is a real or imaginary two-dimensional closed surface that encloses or demarcates the volume or region that a thermodynamic system occupies, across which quantities such as heat, mass, or work can flow.[5] In short, a thermodynamic boundary is a geometrical division between a system and its surroundings. Topologically, it is usually considered nearly or piecewise smoothly homeomorphic with a two-sphere, because a system is usually considered simply connected.

Boundaries can also be fixed (e.g. a constant volume reactor) or moveable (e.g. a piston). For example, in a reciprocating engine, a fixed boundary means the piston is locked at its position; as such, a constant volume process occurs. In that same engine, a moveable boundary allows the piston to move in and out. Boundaries may be real or imaginary. For closed systems, boundaries are real while for open system boundaries are often imaginary. For theoretical purposes, a boundary may be declared adiabatic, isothermal, diathermal, insulating, permeable, or semipermeable—but actual physical materials that provide such idealized properties are not always readily available.

Anything that passes across the boundary that effects a change in the internal energy must be accounted for in the energy balance equation. The volume can be the region surrounding a single atom resonating energy, such as Max Planck defined in 1900; it can be a body of steam or air in a steam engine, such as Sadi Carnot defined in 1824; it can be the body of a tropical cyclone, such as Kerry Emanuel theorized in 1986 in the field of atmospheric thermodynamics; it could also be just one nuclide (i.e. a system of quarks) as hypothesized in quantum thermodynamics.

Surroundings

The system is the part of the universe being studied, while the surroundings is the remainder of the universe that lies outside the boundaries of the system. It is also known as the environment, and the reservoir. Depending on the type of system, it may interact with the system by exchanging mass, energy (including heat and work), momentum, electric charge, or other conserved properties. The environment is ignored in analysis of the system, except in regards to these interactions.

Open system

In an open system, matter may flow in and out of some segments of the system boundaries. There may be other segments of the system boundaries that pass heat or work but not matter. Respective account is kept of the transfers of energy across those and any other several boundary segments.

Flow process

The region of space enclosed by open system boundaries is usually called a control volume. It may or may not correspond to physical walls. It is convenient to define the shape of the control volume so that all flow of matter, in or out, occurs perpendicular to its surface. One may consider a process in which the matter flowing into and out of the system is chemically homogeneous.[6] Then the inflowing matter performs work as if it were driving a piston of fluid into the system. Also, the system performs work as if it were driving out a piston of fluid. Through the system walls that do not pass matter, heat (δQ) and work (δW) transfers may be defined, including shaft work.

Classical thermodynamics considers processes for a system that is initially and finally in its own internal state of thermodynamic equilibrium, with no flow. This is feasible also under some restrictions, if the system is a mass of fluid flowing at a uniform rate. Then for many purposes a process, called a flow process, may be considered in accord with classical thermodynamics as if the classical rule of no flow were effective.[7] For the present introductory account, it is supposed that the kinetic energy of flow, and the potential energy of elevation in the gravity field, do not change, and that the walls, other than the matter inlet and outlet, are rigid and motionless.

Under these conditions, the first law of thermodynamics for a flow process states: the increase in the internal energy of a system is equal to the amount of energy added to the system by matter flowing in and by heating, minus the amount lost by matter flowing out and in the form of work done by the system. Under these conditions, the first law for a flow process is written:

where Uin and Uout respectively denote the average internal energy entering and leaving the system with the flowing matter.

There are then two types of work performed: 'flow work' described above, which is performed on the fluid in the control volume (this is also often called 'PV work'), and 'shaft work', which may be performed by the fluid in the control volume on some mechanical device with a shaft. These two types of work are expressed in the equation:

Substitution into the equation above for the control volume cv yields:

The definition of enthalpy, H = U + PV, permits us to use this thermodynamic potential to account jointly for internal energy U and PV work in fluids for a flow process:

During steady-state operation of a device (see turbine, pump, and engine), any system property within the control volume is independent of time. Therefore, the internal energy of the system enclosed by the control volume remains constant, which implies that dUcv in the expression above may be set equal to zero. This yields a useful expression for the power generation or requirement for these devices with chemical homogeneity in the absence of chemical reactions:

This expression is described by the diagram above.

Selective transfer of matter

For a thermodynamic process, the precise physical properties of the walls and surroundings of the system are important, because they determine the possible processes.

An open system has one or several walls that allow transfer of matter. To account for the internal energy of the open system, this requires energy transfer terms in addition to those for heat and work. It also leads to the idea of the chemical potential.

A wall selectively permeable only to a pure substance can put the system in diffusive contact with a reservoir of that pure substance in the surroundings. Then a process is possible in which that pure substance is transferred between system and surroundings. Also, across that wall a contact equilibrium with respect to that substance is possible. By suitable thermodynamic operations, the pure substance reservoir can be dealt with as a closed system. Its internal energy and its entropy can be determined as functions of its temperature, pressure, and mole number.

A thermodynamic operation can render impermeable to matter all system walls other than the contact equilibrium wall for that substance. This allows the definition of an intensive state variable, with respect to a reference state of the surroundings, for that substance. The intensive variable is called the chemical potential; for component substance i it is usually denoted μi. The corresponding extensive variable can be the number of moles Ni of the component substance in the system.

For a contact equilibrium across a wall permeable to a substance, the chemical potentials of the substance must be same on either side of the wall. This is part of the nature of thermodynamic equilibrium, and may be regarded as related to the zeroth law of thermodynamics.[8]

Closed system

In a closed system, no mass may be transferred in or out of the system boundaries. The system always contains the same amount of matter, but heat and work can be exchanged across the boundary of the system. Whether a system can exchange heat, work, or both is dependent on the property of its boundary.

- Adiabatic boundary – not allowing any heat exchange: A thermally isolated system

- Rigid boundary – not allowing exchange of work: A mechanically isolated system

One example is fluid being compressed by a piston in a cylinder. Another example of a closed system is a bomb calorimeter, a type of constant-volume calorimeter used in measuring the heat of combustion of a particular reaction. Electrical energy travels across the boundary to produce a spark between the electrodes and initiates combustion. Heat transfer occurs across the boundary after combustion but no mass transfer takes place either way.

Beginning with the first law of thermodynamics for an open system, this is expressed as:

where U is internal energy, Q is the heat added to the system, W is the work done by the system, and since no mass is transferred in or out of the system, both expressions involving mass flow are zero and the first law of thermodynamics for a closed system is derived. The first law of thermodynamics for a closed system states that the increase of internal energy of the system equals the amount of heat added to the system minus the work done by the system. For infinitesimal changes the first law for closed systems is stated by:

If the work is due to a volume expansion by dV at a pressure P than:

For a homogeneous system, in which only reversible processes can take place, the second law of thermodynamics reads:

where T is the absolute temperature and S is the entropy of the system. With these relations the fundamental thermodynamic relationship, used to compute changes in internal energy, is expressed as:

For a simple system, with only one type of particle (atom or molecule), a closed system amounts to a constant number of particles. However, for systems undergoing a chemical reaction, there may be all sorts of molecules being generated and destroyed by the reaction process. In this case, the fact that the system is closed is expressed by stating that the total number of each elemental atom is conserved, no matter what kind of molecule it may be a part of. Mathematically:

where Nj is the number of j-type molecules, aij is the number of atoms of element i in molecule j and bi0 is the total number of atoms of element i in the system, which remains constant, since the system is closed. There is one such equation for each element in the system.

Isolated system

An isolated system is more restrictive than a closed system as it does not interact with its surroundings in any way. Mass and energy remains constant within the system, and no energy or mass transfer takes place across the boundary. As time passes in an isolated system, internal differences in the system tend to even out and pressures and temperatures tend to equalize, as do density differences. A system in which all equalizing processes have gone practically to completion is in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium.

Truly isolated physical systems do not exist in reality (except perhaps for the universe as a whole), because, for example, there is always gravity between a system with mass and masses elsewhere.[9][10][11][12][13] However, real systems may behave nearly as an isolated system for finite (possibly very long) times. The concept of an isolated system can serve as a useful model approximating many real-world situations. It is an acceptable idealization used in constructing mathematical models of certain natural phenomena.

In the attempt to justify the postulate of entropy increase in the second law of thermodynamics, Boltzmann’s H-theorem used equations, which assumed that a system (for example, a gas) was isolated. That is all the mechanical degrees of freedom could be specified, treating the walls simply as mirror boundary conditions. This inevitably led to Loschmidt's paradox. However, if the stochastic behavior of the molecules in actual walls is considered, along with the randomizing effect of the ambient, background thermal radiation, Boltzmann’s assumption of molecular chaos can be justified.

The second law of thermodynamics for isolated systems states that the entropy of an isolated system not in equilibrium tends to increase over time, approaching maximum value at equilibrium. Overall, in an isolated system, the internal energy is constant and the entropy can never decrease. A closed system's entropy can decrease e.g. when heat is extracted from the system.

It is important to note that isolated systems are not equivalent to closed systems. Closed systems cannot exchange matter with the surroundings, but can exchange energy. Isolated systems can exchange neither matter nor energy with their surroundings, and as such are only theoretical and do not exist in reality (except, possibly, the entire universe).

It is worth noting that 'closed system' is often used in thermodynamics discussions when 'isolated system' would be correct - i.e. there is an assumption that energy does not enter or leave the system.

Mechanically isolated system

A mechanically isolated system can exchange no work energy with its environment, but may exchange heat energy and/or mass with its environment. The internal energy of a mechanically isolated system may therefore change due to the exchange of heat energy and mass. For a simple system, mechanical isolation is equivalent to constant volume and any process which occurs in such a simple system is said to be isochoric.

Systems in equilibrium

At thermodynamic equilibrium, a system's properties are, by definition, unchanging in time. Systems in equilibrium are much simpler and easier to understand than systems not in equilibrium. In some cases, when analyzing a thermodynamic process, one can assume that each intermediate state in the process is at equilibrium. This considerably simplifies the analysis.

In isolated systems it is consistently observed that as time goes on internal rearrangements diminish and stable conditions are approached. Pressures and temperatures tend to equalize, and matter arranges itself into one or a few relatively homogeneous phases. A system in which all processes of change have gone practically to completion is considered in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium. The thermodynamic properties of a system in equilibrium are unchanging in time. Equilibrium system states are much easier to describe in a deterministic manner than non-equilibrium states.

For a process to be reversible, each step in the process must be reversible. For a step in a process to be reversible, the system must be in equilibrium throughout the step. That ideal cannot be accomplished in practice because no step can be taken without perturbing the system from equilibrium, but the ideal can be approached by making changes slowly.

See also

References

- ^ Eu, B.C. (2002). Generalized Thermodynamics. The Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes and Generalized Hydrodynamics, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, ISBN 1-4020-0788-4.

- ^ Bailyn, M. (1994). A Survey of Thermodynamics, American Institute of Physics Press, New York, ISBN 0-88318-797-3, p. 20.

- ^ Tisza, L. (1966). Generalized Thermodynamics, M.I.T Press, Cambridge MA, p. 119.

- ^ Bailyn, M. (1994). A Survey of Thermodynamics, American Institute of Physics Press, New York, ISBN 0-88318-797-3, p. 22.

- ^ Perrot, Pierre (1998). A to Z of Thermodynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856552-6.

- ^ Shavit, A., Gutfinger, C. (1995). Thermodynamics. From Concepts to Applications, Prentice Hall, London, ISBN 0-13-288267-1, Chapter 6.

- ^ Adkins, C.J. (1968/1983). Equilibrium Thermodynamics, third edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, ISBN 0-521-25445-0, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Bailyn, M. (1994). A Survey of Thermodynamics, American Institute of Physics Press, New York, ISBN 0-88318-797-3, pp. 19–23.

- ^ I.M.Kolesnikov; V.A.Vinokurov; S.I.Kolesnikov (2001). Thermodynamics of Spontaneous and Non-Spontaneous Processes. Nova science Publishers. p. 136. ISBN 1-56072-904-X.

- ^ "A System and Its Surroundings". ChemWiki. University of California - Davis. Retrieved May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Hyperphysics". The Department of Physics and Astronomy of Georgia State University. Retrieved May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Bryan Sanctuary. "Open, Closed and Isolated Systems in Physical Chemistry,". Foundations of Quantum Mechanics and Physical Chemistry. McGill University (Montreal). Retrieved May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Material and Energy Balances for Engineers and Environmentalists (PDF). Imperial College Press. p. 7. Retrieved May 2012.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

- Abbott, M.M.; van Hess, H.G. (1989). Thermodynamics with Chemical Applications (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill.

- Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; Walker, Jearl (2008). Fundamentals of Physics (8th ed.). Wiley.

- Moran, Michael J.; Shapiro, Howard N. (2008). Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics (6th ed.). Wiley.

External links

- http://www.hasdeu.bz.edu.ro/softuri/fizica/mariana/Termodinamica/1stLaw_1/close.htm

- https://www.e-education.psu.edu/png520/m14_p4.html