RYB color model: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→History: prior art |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

Please, demonstrate relevance to the RYB model. Goethe was more interested in visual perception rather than in mixing of paints. --> |

Please, demonstrate relevance to the RYB model. Goethe was more interested in visual perception rather than in mixing of paints. --> |

||

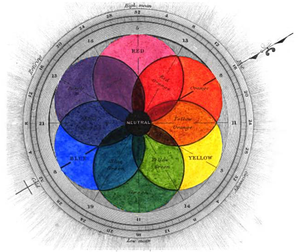

[[File:Chromatography 1841 Field.png|right|thumb|300px|An RYB color chart from [[George Field (chemist)|George Field]]'s 1841 ''Chromatography; or, A treatise on colours and pigments: and of their powers in painting'' showing a red close to magenta and a blue close to cyan, as is typical in printing.]] |

[[File:Chromatography 1841 Field.png|right|thumb|300px|An RYB color chart from [[George Field (chemist)|George Field]]'s 1841 ''Chromatography; or, A treatise on colours and pigments: and of their powers in painting'' showing a red close to magenta and a blue close to cyan, as is typical in printing.]] |

||

The first known instance of the RYB triumvirate can be found in the work of Franciscus Aguilonius (1567-1617)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140213041900/http://www.colorsystem.com/?page_id=629&lang=en}}</ref> though he did not arrange the colours in a wheel. |

|||

In his experiments with light, [[Isaac Newton]] recognized that colors could be created by mixing color primaries. In his ''[[Opticks]]'', Newton published a color wheel to show the geometric relationship between these primaries. This chart was later confused and understood to apply to pigments as well,<ref name=hprint1>{{cite web | last = MacEvoy | first = Bruce | title = handprint : color wheels | date = April 19, 2009 | url = http://handprint.com/HP/WCL/color13.html | accessdate = 2009-06-30}}</ref> though Newton was also unaware of the differences between additive and subtractive color mixing.<ref name=hprint2>{{cite web | last = MacEvoy | first = Bruce | title = handprint : do "primary" colors exist? | date = April 19, 2009 | url = http://handprint.com/HP/WCL/color6.html#confusions | accessdate = 2009-06-30}}</ref> |

In his experiments with light, [[Isaac Newton]] recognized that colors could be created by mixing color primaries. In his ''[[Opticks]]'', Newton published a color wheel to show the geometric relationship between these primaries. This chart was later confused and understood to apply to pigments as well,<ref name=hprint1>{{cite web | last = MacEvoy | first = Bruce | title = handprint : color wheels | date = April 19, 2009 | url = http://handprint.com/HP/WCL/color13.html | accessdate = 2009-06-30}}</ref> though Newton was also unaware of the differences between additive and subtractive color mixing.<ref name=hprint2>{{cite web | last = MacEvoy | first = Bruce | title = handprint : do "primary" colors exist? | date = April 19, 2009 | url = http://handprint.com/HP/WCL/color6.html#confusions | accessdate = 2009-06-30}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:41, 8 October 2014

RYB (an abbreviation of red–yellow–blue) is a historical set of colors used in subtractive color mixing, and is one commonly used set of primary colors. It is primarily used in art and design education, particularly painting.

RYB predates modern scientific color theory, which argues that magenta, yellow, and cyan are the best set of three colorants to combine, for the widest range of high-chroma colors.[1] Red can be produced by mixing magenta and yellow, blue can be produced by mixing cyan and magenta, and green can be produced by mixing yellow and cyan. In the RYB model, red takes the place of magenta, and blue takes the place of cyan.

However, reproducing the entire range of human color vision with three primaries either in an additive or subtractive fashion is generally not possible; see gamut for more information.

Color wheel

RYB (red–yellow–blue) make up the primary color triad in a standard artist's color wheel. The secondary colors purple–orange–green (sometimes called violet–orange–green) make up another triad. Triads are formed by 3 equidistant colors on a particular color wheel. Other common color wheels represent the light model (RGB) and the print model (CMYK).

History

The first known instance of the RYB triumvirate can be found in the work of Franciscus Aguilonius (1567-1617)[2] though he did not arrange the colours in a wheel.

In his experiments with light, Isaac Newton recognized that colors could be created by mixing color primaries. In his Opticks, Newton published a color wheel to show the geometric relationship between these primaries. This chart was later confused and understood to apply to pigments as well,[3] though Newton was also unaware of the differences between additive and subtractive color mixing.[4]

The RYB model was used for printing, by Jacob Christoph Le Blon, as early as 1725.

In the 18th century, the RYB primary colors became the foundation of theories of color vision, as the fundamental sensory qualities that are blended in the perception of all physical colors and equally in the physical mixture of pigments or dyes. These theories were enhanced by 18th-century investigations of a variety of purely psychological color effects, in particular the contrast between "complementary" or opposing hues that are produced by color afterimages and in the contrasting shadows in colored light. These ideas and many personal color observations were summarized in two founding documents in color theory: the Theory of Colors (1810) by the German poet and government minister Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and The Law of Simultaneous Color Contrast (1839) by the French industrial chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul.

Painters have long used more than three RYB primary colors in their palettes – and at one point considered red, yellow, blue, and green to be the four primaries.[5] Red, yellow, blue, and green are still widely considered the four psychological primary colors,[6] though red, yellow, and blue are sometimes listed as the three psychological primaries,[7] with black and white occasionally added as a fourth and fifth.[8]

The cyan, magenta, and yellow primary colors associated with CMYK printing are sometimes known as "process blue", "process red",[citation needed] and "process yellow".

Modern understanding

Starting from Goethe, it was increasingly understood that mixing of colored light in the eye is a process different from mixing of dyes. Subsequently, German and English scientists established in the late 19th century that color perception is best described in terms of a different set of primary colors – red, green, and blue (RGB) modeled through the additive, rather than subtractive, mixture of three monochromatic lights, also known as spectral colors. Although traditionally a broad color term, "red" started to refer to its meaning in this theory, namely to the low frequency (or long wavelength) end of the visible spectrum. It is not necessarily the same hue which painters or chemists (such as George Field) understood as "red", because their experience was centered on pigments, not beams of light. Similarly, modern standard blue is only one of different hues traditionally described as "blue". Hence, some care is required to understand exactly which colors past authors used in their models.

See also

References

- ^ James Gurney (2010). Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-7407-9771-2.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20140213041900/http://www.colorsystem.com/?page_id=629&lang=en.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ MacEvoy, Bruce (April 19, 2009). "handprint : color wheels". Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ^ MacEvoy, Bruce (April 19, 2009). "handprint : do "primary" colors exist?". Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ^ For instance Leonardo da Vinci wrote of these four simple colors in his notebook circa 1500. See Rolf Kuenhi. “Development of the Idea of Simple Colors in the 16th and Early 17th Centuries”. Color Research and Application. Volume 32, Number 2, April 2007.

- ^ Resultby Leslie D. Stroebel, Ira B. Current (2000). Basic Photographic Materials and Processes. Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-80345-0.

- ^ MS Sharon Ross

, Elise Kinkead (2004). Decorative Painting & Faux Finishes. Creative Homeowner. ISBN 1-58011-179-3.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|author=at position 15 (help) - ^ Swirnoff, Lois (2003). Dimensional Color. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-73102-2.