Anders' Army: Difference between revisions

m →Establishment in the Soviet Union: 1 wikilink |

Rescuing 3 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.4) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==Establishment in the Soviet Union== |

==Establishment in the Soviet Union== |

||

At the start of the [[Soviet invasion of Poland]] (17 September 1939), the Soviets declared that the Polish state, previously [[Invasion of Poland|invaded by Axis forces]] on 1 September 1939, no longer existed, effectively breaking off [[Soviet-Polish relations]].<ref name="SCHULENBURG">See telegrams: [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/nazsov/ns069.htm No. 317 of September 10]: Schulenburg, the German ambassador in the Soviet Union, to the German Foreign Office. Moscow, September 10, 1939–9:40 p.m.; [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/nazsov/ns073.htm No. 371 of September 16]; [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/nazsov/ns074.htm No. 372 of September 17] Source: The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Last accessed on 14 November 2006; {{pl icon}} [http://ibidem.com.pl/zrodla/1939-1945/polityka-miedzynarodowa/1939-09-17-nota-sowiecka-grzybowskiemu.html 1939 wrzesień 17, Moskwa Nota rządu sowieckiego nie przyjęta przez ambasadora Wacława Grzybowskiego] (Note of the Soviet government to the Polish government on 17 September 1939 refused by Polish ambassador Wacław Grzybowski). Last accessed on 15 November 2006.</ref> Soviet authorities deported about 325,000 Polish citizens from [[Territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union|Soviet-occupied Poland]] to the Soviet Union in 1940–41.<ref name="Brzoza Sowa Historia Polski 1918–1945 695">Czesław Brzoza, Andrzej Leon Sowa, ''Historia Polski 1918–1945'' [History of Poland: 1918–1945], p. 695. Kraków 2009, [[Wydawnictwo Literackie]], {{ISBN|978-83-08-04125-3}}.</ref> Due to British mediation and pressure, the Soviet Union and the [[Polish government-in-exile]] (then based in London) re-established Polish-Soviet diplomatic relations in July 1941 after the [[Operation Barbarossa|German invasion of the Soviet Union]] started on 22 June 1941. The [[Sikorski–Mayski agreement]] of 30 July 1941 resulted in the Soviet Union agreeing to invalidate the territorial aspects of the pacts it had had with [[Nazi Germany]] and to release tens of thousands of Polish [[Prisoner of war|prisoners-of-war]] held in Soviet camps. Pursuant to the agreement between the [[Polish government-in-exile]] and the Soviet Union, the Soviets granted "[[Amnesty for Polish citizens in the Soviet Union|amnesty]]" to many Polish citizens, from whom a military force was formed. A Polish-Soviet military agreement was signed on 14 August 1941; it attempted to specify the political and operational conditions for the functioning of the Polish army on Soviet soil. Stalin agreed that this force would be subordinate to the Polish government-in-exile, while operationally being a part of the Soviet-German [[Eastern Front (World War II)|Eastern Front]].<ref name="Kochanski 163–173">[[Halik Kochanski]] (2012). The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War, pp. 163–173. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. {{ISBN|978-0-674-06814-8}}.</ref> |

At the start of the [[Soviet invasion of Poland]] (17 September 1939), the Soviets declared that the Polish state, previously [[Invasion of Poland|invaded by Axis forces]] on 1 September 1939, no longer existed, effectively breaking off [[Soviet-Polish relations]].<ref name="SCHULENBURG">See telegrams: [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/nazsov/ns069.htm No. 317 of September 10] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091107175858/http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/nazsov/ns069.htm |date=2009-11-07 }}: Schulenburg, the German ambassador in the Soviet Union, to the German Foreign Office. Moscow, September 10, 1939–9:40 p.m.; [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/nazsov/ns073.htm No. 371 of September 16] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070430203034/http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/nazsov/ns073.htm |date=2007-04-30 }}; [http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/nazsov/ns074.htm No. 372 of September 17] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070430142631/http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/nazsov/ns074.htm |date=2007-04-30 }} Source: The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Last accessed on 14 November 2006; {{pl icon}} [http://ibidem.com.pl/zrodla/1939-1945/polityka-miedzynarodowa/1939-09-17-nota-sowiecka-grzybowskiemu.html 1939 wrzesień 17, Moskwa Nota rządu sowieckiego nie przyjęta przez ambasadora Wacława Grzybowskiego] (Note of the Soviet government to the Polish government on 17 September 1939 refused by Polish ambassador Wacław Grzybowski). Last accessed on 15 November 2006.</ref> Soviet authorities deported about 325,000 Polish citizens from [[Territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union|Soviet-occupied Poland]] to the Soviet Union in 1940–41.<ref name="Brzoza Sowa Historia Polski 1918–1945 695">Czesław Brzoza, Andrzej Leon Sowa, ''Historia Polski 1918–1945'' [History of Poland: 1918–1945], p. 695. Kraków 2009, [[Wydawnictwo Literackie]], {{ISBN|978-83-08-04125-3}}.</ref> Due to British mediation and pressure, the Soviet Union and the [[Polish government-in-exile]] (then based in London) re-established Polish-Soviet diplomatic relations in July 1941 after the [[Operation Barbarossa|German invasion of the Soviet Union]] started on 22 June 1941. The [[Sikorski–Mayski agreement]] of 30 July 1941 resulted in the Soviet Union agreeing to invalidate the territorial aspects of the pacts it had had with [[Nazi Germany]] and to release tens of thousands of Polish [[Prisoner of war|prisoners-of-war]] held in Soviet camps. Pursuant to the agreement between the [[Polish government-in-exile]] and the Soviet Union, the Soviets granted "[[Amnesty for Polish citizens in the Soviet Union|amnesty]]" to many Polish citizens, from whom a military force was formed. A Polish-Soviet military agreement was signed on 14 August 1941; it attempted to specify the political and operational conditions for the functioning of the Polish army on Soviet soil. Stalin agreed that this force would be subordinate to the Polish government-in-exile, while operationally being a part of the Soviet-German [[Eastern Front (World War II)|Eastern Front]].<ref name="Kochanski 163–173">[[Halik Kochanski]] (2012). The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War, pp. 163–173. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. {{ISBN|978-0-674-06814-8}}.</ref> |

||

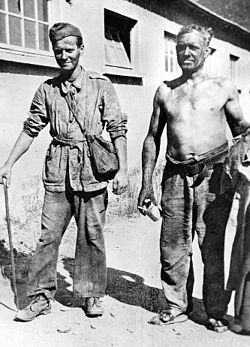

[[Image:Jangi-Yul.JPG|thumb|250px|right|Officers of the Polish and Soviet armies during exercises in the winter of 1941. [[Władysław Anders]] is sitting on the right.]] |

[[Image:Jangi-Yul.JPG|thumb|250px|right|Officers of the Polish and Soviet armies during exercises in the winter of 1941. [[Władysław Anders]] is sitting on the right.]] |

||

Revision as of 21:52, 4 July 2017

Anders' Army was the informal yet common name of the Polish Armed Forces in the East in the 1941–42 period, in recognition of its commander Władysław Anders. The army was created in the Soviet Union but in March 1942, based on the British-Soviet-Polish understanding, it was evacuated from the Soviet Union and made its way through Iran to Palestine. There it passed under British command and provided the bulk of the units and troops of the Polish II Corps (member of the Polish Armed Forces in the West), which fought in the Italian Campaign.

Establishment in the Soviet Union

At the start of the Soviet invasion of Poland (17 September 1939), the Soviets declared that the Polish state, previously invaded by Axis forces on 1 September 1939, no longer existed, effectively breaking off Soviet-Polish relations.[1] Soviet authorities deported about 325,000 Polish citizens from Soviet-occupied Poland to the Soviet Union in 1940–41.[2] Due to British mediation and pressure, the Soviet Union and the Polish government-in-exile (then based in London) re-established Polish-Soviet diplomatic relations in July 1941 after the German invasion of the Soviet Union started on 22 June 1941. The Sikorski–Mayski agreement of 30 July 1941 resulted in the Soviet Union agreeing to invalidate the territorial aspects of the pacts it had had with Nazi Germany and to release tens of thousands of Polish prisoners-of-war held in Soviet camps. Pursuant to the agreement between the Polish government-in-exile and the Soviet Union, the Soviets granted "amnesty" to many Polish citizens, from whom a military force was formed. A Polish-Soviet military agreement was signed on 14 August 1941; it attempted to specify the political and operational conditions for the functioning of the Polish army on Soviet soil. Stalin agreed that this force would be subordinate to the Polish government-in-exile, while operationally being a part of the Soviet-German Eastern Front.[3]

On 4 August 1941 the Polish Prime minister and Commander-in_Chief, General Władysław Sikorski, nominated General Władysław Anders, just released from the Lubyanka prison in Moscow, as commander of the army. General Michał Tokarzewski began the task of forming the army in the Soviet town of Totskoye in Orenburg Oblast on 17 August. Anders announced his appointment and issued his first orders on 22 August.

The formation began organizing in the Buzuluk area, and recruitment began in the NKVD camps among Polish POWs. By the end of 1941 the new Polish force had recruited 25,000 soldiers (including 1,000 officers), forming three infantry divisions: 5th, 6th and 7th. Menachem Begin (the future leader of the anti-British resistance group Irgun, Prime Minister of Israel and Nobel Peace Prize winner) was among those who joined. In the spring of 1942 the organizing center moved to the area of Tashkent in Uzbekistan and the 8th division was also formed.

The recruitment process met obstacles. Significant numbers of Polish officers were missing as a result of the Katyn massacre (1940), unknown at that time to the Poles. The Soviets did not want citizens of the Second Polish Republic who were not ethnic Poles (such as Jews, Belarusians and Ukrainians) to be eligible for recruitment. The newly established military units did not receive proper logistical support or supplies. Some administrators of Soviet camps holding the Poles interfered with the already authorized release of their Polish inmates.[citation needed]

The Soviets, coping with the deteriorating war situation, were unable to provide adequate food rations for the growing Polish army, which was sharing its limited provisions with the also growing group of Polish civilian deportees.[4] After the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran (August–September 1941), Stalin agreed on 18 March 1942 to evacuate part of the Polish formation as a military force to Iran, and the soldiers transferred across the Caspian Sea to the port of Pahlavi in Iran. Eventually all the soldiers and civilians gathered were allowed to leave the Soviet Union and to enter British-controlled territories.

Under British command

More military and civilian men, women and children were transferred later that summer, through the end of August, by ship and by an overland route from Ashgabat, Turkmenistan to the railhead in Mashhad, Iran. Thousands of former Polish prisoners had to walk from the southern border of the Soviet Union to Iran. Many died due to cold weather, hunger, and exhaustion. About 79,000 soldiers and 37,000 civilians – Polish citizens – were able to leave the Soviet Union.[5] Anders' Army was transferred to the operational control of the British government; it was placed under the British Middle East Command, traveling through Iran, Iraq and Palestine. Many of its soldiers joined the Polish Second Corps, a part of Polish Armed Forces in the West. With the corps, troops from Anders' Army fought in the Italian Campaign, including the Battle of Monte Cassino. Their contribution is highly valued in Poland and frequently commemorated in names of streets and other places.

Jewish soldiers and civilians

When Anders' Army left the Soviet Union on its journey towards the Middle East, families of the soldiers and groups of Jewish children, war orphans, joined the Jewish soldiers. After arriving in Tehran, Iran, the children were transferred into the hands of the emissaries who brought them to Palestine.

When Anders' Army reached Palestine, of its over four thousand Jewish soldiers three thousand left the army.[6] Some deserted, while others, including Menachem Begin, obtained permissions to depart their formations. They joined the veteran settlements in the region. The Polish army had not pursued the Jewish deserters.

In 2006, a memorial to Anders' Army was erected in the orthodox cemetery on Mount Zion in Jerusalem.

Notable veterans of Anders' Army

- Menachem Begin, the sixth prime minister (1977–1983) of Israel

- Vincent Zhuk-Hryshkevich, the future president of the Belarusian Democratic Republic in exile

- Alexander Nadson, the future well-known Belarusian religious leader and Apostolic Visitor for the Belarusian Greek-Catholic faithful abroad

- Nikodem Sulik

- Alfons Maniura

- Leonid Teliga

- Stanisław Szostak

- Julian J. Bussgang, author of the Bussgang Theorem

Norman Davies' Trail of Hope

Norman Davies published his story of General Anders' Second Corps in Polish.[7][8][9][10]

References

- ^ See telegrams: No. 317 of September 10 Archived 2009-11-07 at the Wayback Machine: Schulenburg, the German ambassador in the Soviet Union, to the German Foreign Office. Moscow, September 10, 1939–9:40 p.m.; No. 371 of September 16 Archived 2007-04-30 at the Wayback Machine; No. 372 of September 17 Archived 2007-04-30 at the Wayback Machine Source: The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Last accessed on 14 November 2006; Template:Pl icon 1939 wrzesień 17, Moskwa Nota rządu sowieckiego nie przyjęta przez ambasadora Wacława Grzybowskiego (Note of the Soviet government to the Polish government on 17 September 1939 refused by Polish ambassador Wacław Grzybowski). Last accessed on 15 November 2006.

- ^ Czesław Brzoza, Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia Polski 1918–1945 [History of Poland: 1918–1945], p. 695. Kraków 2009, Wydawnictwo Literackie, ISBN 978-83-08-04125-3.

- ^ Halik Kochanski (2012). The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War, pp. 163–173. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06814-8.

- ^ Anders, Lt.-General Wladyslaw. An Army in Exile. MacMillan & Co. Ltd, 1949, pp. 98–100.

- ^ Czesław Brzoza, Andrzej Leon Sowa, Historia Polski 1918–1945 [History of Poland: 1918–1945], p. 531.

- ^ Halik Kochanski (2012). The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Szlak nadziei Rosikon press

- ^ Trail of Hope

- ^ Norman Davies on the Trail of Anders' Army

- ^ "Trail of Hope" – The footsteps of the Anders Army