Ball python: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.4) |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''ball python''' (''Python regius''), also known as the '''royal python''',<ref name="Meh87">Mehrtens JM. 1987. Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. {{ISBN|0-8069-6460-X}}.</ref> is a [[Pythonidae|python]] [[species]] found in sub-Saharan [[Africa]]. Like all other pythons, it is a [[venom|non-venomous]] [[Constriction|constrictor]]. This is the smallest of the African pythons and is popular in the pet trade, largely due to its small size and typically docile temperament. No [[subspecies]] are currently recognized.<ref name="ITIS">{{ITIS |id=634784 |taxon=''Python regius'' |accessdate=12 September 2007}}</ref> The name "ball python" refers to the animal's tendency to curl into a ball when stressed or frightened.<ref name="BPN">[http://www.ball-pythons.net/modules.php?name=Sections&op=viewarticle&id=59 Ball Python (''Python regius'') Caresheet] at [http://www.ball-pythons.net/ ball-pythons.net]. Accessed 12 September 2007.</ref> The name "royal python"(from the Latin ''regius'') comes from the fact that rulers in Africa would wear the python as jewelry.{{citation needed|date = May 2017}} |

The '''ball python''' (''Python regius''), also known as the '''royal python''',<ref name="Meh87">Mehrtens JM. 1987. Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. {{ISBN|0-8069-6460-X}}.</ref> is a [[Pythonidae|python]] [[species]] found in sub-Saharan [[Africa]]. Like all other pythons, it is a [[venom|non-venomous]] [[Constriction|constrictor]]. This is the smallest of the African pythons and is popular in the pet trade, largely due to its small size and typically docile temperament. No [[subspecies]] are currently recognized.<ref name="ITIS">{{ITIS |id=634784 |taxon=''Python regius'' |accessdate=12 September 2007}}</ref> The name "ball python" refers to the animal's tendency to curl into a ball when stressed or frightened.<ref name="BPN">[http://www.ball-pythons.net/modules.php?name=Sections&op=viewarticle&id=59 Ball Python (''Python regius'') Caresheet] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070523102853/http://www.ball-pythons.net/modules.php?name=Sections&op=viewarticle&id=59 |date=23 May 2007 }} at [http://www.ball-pythons.net/ ball-pythons.net]. Accessed 12 September 2007.</ref> The name "royal python"(from the Latin ''regius'') comes from the fact that rulers in Africa would wear the python as jewelry.{{citation needed|date = May 2017}} |

||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

Revision as of 05:11, 14 July 2017

| Ball python | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Pythonidae |

| Genus: | Python |

| Species: | P. regius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Python regius (Shaw, 1802)

| |

| Synonyms | |

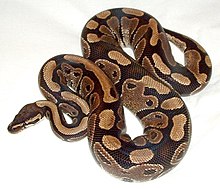

The ball python (Python regius), also known as the royal python,[2] is a python species found in sub-Saharan Africa. Like all other pythons, it is a non-venomous constrictor. This is the smallest of the African pythons and is popular in the pet trade, largely due to its small size and typically docile temperament. No subspecies are currently recognized.[3] The name "ball python" refers to the animal's tendency to curl into a ball when stressed or frightened.[4] The name "royal python"(from the Latin regius) comes from the fact that rulers in Africa would wear the python as jewelry.[citation needed]

Description

Maximum adult length of this species is 182 cm (6.0 ft).[5] Females tend to be slightly bigger than males, maturing at an average of 122–137 cm (4.0–4.5 ft). Males usually average around 90–107 cm (3.0–3.5 ft).[6] The build is stocky[2] while the head is relatively small. The scales are smooth[5] and both sexes have anal spurs on either side of the vent.[7] Although males tend to have larger spurs, this is not definitive, and sex is best determined via manual eversion of the male hemipenes or inserting a probe into the cloaca to check the presence of an inverted hemipenis (if male).[8] When probing to determine sex, males typically measure eight to 10 subcaudal scales, and females typically measure two to four subcaudal scales.[5]

The color pattern is typically black or dark brown with light brown or gold sides and dorsal blotches. The belly is a white or cream that may include scattered black markings.[5] However, those in the pet industries have, through selective breeding, developed many morphs (genetic mutations) with altered colors and patterns.[9]

Distribution and habitat

They are found in west Africa from Senegal, Mali, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Benin, and Nigeria through Cameroon, Chad and the Central African Republic to Sudan and Uganda. No type locality was given in the original description.[1]

The ball python bears a strong physical resemblance to the Burmese python whose adaptive abilities have caused it to become classified as an invasive species in places such as the Florida Everglades. The ball python, however, has not been known to reproduce in the wild outside of its native range and there are no known reproducing wild populations in Florida.[10]

Ball pythons prefer grasslands, savannas, and sparsely wooded areas.[2] Termite mounds and empty mammal burrows are important habitats for this species.

Behaviour

This terrestrial species is known for its defense strategy that involves coiling into a tight ball when threatened, with its head and neck tucked away in the middle. In this state, it can literally be rolled around. Favored retreats include mammal burrows and other underground hiding places, where they also aestivate. In captivity, they are considered good pets, with their relatively small size and placid nature making them easy to handle.[2]

Feeding

In the wild, their diet consists mostly of small mammals, such as African soft-furred rats, shrews, and striped mice. Younger individuals have also been known to feed on birds.[5]

Reproduction

Females are oviparous, with three to 11 rather large, leathery eggs being laid (four to six are most common).[5] These are incubated by the female under the ground (via a shivering motion), and hatch after 55 to 60 days. Sexual maturity is reached at 11–18 months for males, and 20–36 months for females. Age is only one factor in determining sexual maturity and ability to breed; weight is the second factor. Males breed at 600 g or more, but in captivity are often not bred until they are 800 g (1.7 lb), although in captivity, some males have been known to begin breeding at 300-400 g. Females breed in the wild at weights as low as 800 g though 1200 g or more in weight is most common; in captivity, breeders generally wait until they are no less than 1500 g (3.3 lb). Parental care of the eggs ends once they hatch, and the female leaves the offspring to fend for themselves.[8]

Captivity

Wild-caught specimens have greater difficulty adapting to a captive environment, which can result in refusal to feed, and they generally carry internal or external parasites. Specimens have survived for over 40 years in captivity, with the oldest recorded ball python being kept in captivity 47 years and 6 months until its death in 1992 at the Philadelphia Zoo.[11]

Hundreds of different color patterns are available in captive snakes. Some of the most common are Spider, Pastel, Albino, Mojave, and Lesser. Breeders are continuously creating new designer morphs, and over 3,800 different morphs currently exist.[12]

Beliefs and folklore

This species is particularly revered in the traditional religion of the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria. It is considered symbolic of the earth, being an animal that travels so close to the ground. Even among many Christian Igbos, these pythons are treated with great care whenever they happen to wander into a village or onto someone's property; they are allowed to roam freely or are very gently picked up and placed out in a forest or field away from any homes. If one is accidentally killed, many communities in Igboland still build a coffin for the snake's remains and give it a short funeral.[13]

See also

References

- ^ a b McDiarmid RW, Campbell JA, Touré T. 1999. Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, vol. 1. Herpetologists' League. 511 pp. ISBN 1-893777-00-6 (series). ISBN 1-893777-01-4 (volume).

- ^ a b c d Mehrtens JM. 1987. Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. ISBN 0-8069-6460-X.

- ^ "Python regius". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ Ball Python (Python regius) Caresheet Archived 23 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine at ball-pythons.net. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Barker DG, Barker TM. 2006. Ball Pythons: The History, Natural History, Care and Breeding (Pythons of the World, Volume 2). VPI Library. 320 pp. ISBN 0-9785411-0-3.

- ^ http://www.peteducation.com/article.cfm?c=17+1831&aid=2422

- ^ Ball python at Pet Education. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- ^ a b McCurley, Kevin. 2005. The Complete Ball Python: A Comprehensive Guide to Care, Breeding and Genetic Mutations. ECO & Serpent's Tale Nat Hist Books. 300 pp. ISBN 978-097-131-9.

- ^ (P. regius) Base Mutations at Graziani Reptiles. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Ball python". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ Kate, Frank; Slavens, Kate (2003). "Python longevity records". Reptiles and Amphibians in Captivity – Longevity (at PondTurtle.com). Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ http://www.worldofballpythons.com/morphs/

- ^ Hambly, Wilfrid Dyson; Laufer, Berthold (1931). "Serpent worship". Fieldiana Anthropology. 21 (1).

External links

- Python regius at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- Ball Python Articles and Care Sheets at RC Reptiles.com. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- Ball Python Care and Husbandry at Ball Python Care.

- Ball Python Care Sheet at Herphangout. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- Troubleshooting Guide for Ball Pythons at kingsnake.com. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- Ball Pythons as Pets at About.com: Exotic Pets. Accessed 12 September 2007.

- Ball Python, Python regius Care at ReptileExpert.org. Accessed 4 April 2011.

- Royal Python, Python regius Care at The Royal Python. Accessed 17 December 2012.