Basilica: Difference between revisions

add section |

GPinkerton (talk | contribs) Changing short description from "Form of large building in classical architecture and type of church" to "Form of large public building in classical architecture and type of church" (Shortdesc helper) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Form of large building in classical architecture and type of church}} |

{{short description|Form of large public building in classical architecture and type of church}} |

||

{{About|a form of building|the designation "basilica" in canon law|Basilicas in Roman Catholicism| the Byzantine code of law|Basilika|the genus of moth|Basilica (moth)| the herb|Basil}} |

{{About|a form of building|the designation "basilica" in canon law|Basilicas in Roman Catholicism| the Byzantine code of law|Basilika|the genus of moth|Basilica (moth)| the herb|Basil}} |

||

[[File:BasilicaSemproniaReconstruction.jpg|thumb|Digital reconstruction of the 2nd century BC [[Basilica Sempronia]], in the [[Forum Romanum]].]] |

[[File:BasilicaSemproniaReconstruction.jpg|thumb|Digital reconstruction of the 2nd century BC [[Basilica Sempronia]], in the [[Forum Romanum]].]] |

||

Revision as of 07:26, 9 May 2020

The Latin word basilica refers to large public buildings with multiple functions in Ancient Roman architecture, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to the Stoa in the Greek East. It also refers to the typical architectural form of basilicas.

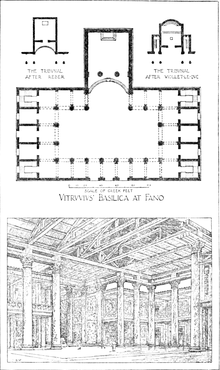

Originally, the word was used to refer to an ancient Roman public building, where courts were held, as well as serving other official and public functions. Basilicas are typically rectangular buildings with a central nave flanked by two or more longitudinal aisles, with the roof at two levels, being higher in the centre over the nave to admit a clerestory and lower over the side-aisles. An apse at one end, or less frequently at both ends or on the side, usually contained the raised tribunal occupied by the Roman magistrates.

The basilica was centrally located in every Roman town, usually adjacent to the main forum. Subsequently, the basilica was not built near a forum but adjacent to a palace and was known as a "palace basilica".

Secondly, as the Roman Empire adopted Christianity, the major church buildings were typically constructed with this basic architectural plan and thus it became popular throughout Europe. It continues to be used in an architectural sense to describe rectangular buildings with a central nave and aisles, and usually a raised platform at the opposite end from the door. In Europe and the Americas the basilica remained the most common architectural style for churches of all Christian denominations, though this building plan has become less dominant in new buildings since the latter 20th century.

Terminology

The Latin word basilica Ancient Greek: βασιλική στοά, romanized: basilikè stoá, lit. 'royal stoa'. In Rome the word was at first used to describe an ancient Roman public building where courts were held, as well as serving other official and public functions. To a large extent these were the town halls of ancient Roman life. The basilica was centrally located in every Roman town, usually adjacent to the main forum. These buildings, an example of which is the Basilica Ulpia, were rectangular, and often had a central nave and aisles, usually with a slightly raised platform and an apse at each of the two ends, adorned with a statue perhaps of the emperor, while the entrances were from the long sides.[1][2]

By extension the name was applied to Christian churches which adopted the same basic plan and it continues to be used as an architectural term to describe such buildings, which form the majority of church buildings in Western Christianity, though the basilican building plan became less dominant in new buildings from the later 20th century.

Architecture

There were several variations of the basic plan of the secular basilica, always some kind of rectangular hall, but the one usually followed for churches had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end opposite to the main door at the other end. In (and often also in front of) the apse was a raised platform, where the altar was placed, and from where the clergy officiated. In secular building this plan was more typically used for the smaller audience halls of the emperors, governors, and the very rich than for the great public basilicas functioning as law courts and other public purposes.[3] Constantine built a basilica of this type in his palace complex at Trier, later very easily adopted for use as a church. It is a long rectangle two storeys high, with ranks of arch-headed windows one above the other, without aisles (there was no mercantile exchange in this imperial basilica) and, at the far end beyond a huge arch, the apse in which Constantine held state.

Basilicas in Roman Catholicism

In the Roman Catholic Church the term basilica refers to an official designation of a certain kind of church in the Roman Catholic Church: a large and important place of worship that has been given special ceremonial rights by the Pope. They need not architecturally be basilicas. Basilicas in this sense are divided into classes, the major ("greater") basilicas and the minor basilicas. Churches designated as papal basilicas, in particular, possess a papal throne and a papal high altar, at which no one may celebrate Mass without the pope's permission.[4]

See also

- Architecture of cathedrals and great churches

- Duomo

- List of basilicas

- Roman architecture

- Roman Catholic Marian churches

References and sources

- References

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture (2013 ISBN 978-0-19968027-6), p. 117

- ^ "The Institute for Sacred Architecture - Articles - The Eschatological Dimension of Church Architecture". www.sacredarchitecture.org.

- ^ Syndicus, 40

- ^ Gietmann, G.; Thurston, Herbert (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

- Sources

- Krautheimer, Richard (1992). Early Christian and Byzantine architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05294-4.

- Architecture of the basilica

- Syndicus, Eduard, Early Christian Art, Burns & Oates, London, 1962

- Basilica Porcia

- W. Thayer, "Basilicas of Ancient Rome": from Samuel Ball Platner (as completed and revised by Thomas Ashby), 1929. A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (London: Oxford University Press)

- Paul Veyne, ed. A History of Private Life I: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium, 1987

- Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Gietmann, G.; Thurston, Herbert (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

Media related to Basilicas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Basilicas at Wikimedia Commons- List of All Major, Patriarchal and Minor Basilicas & statistics by Giga-Catholic Information