2021 Pacific hurricane season

| 2021 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

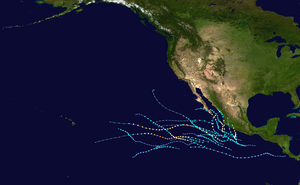

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 9, 2021 |

| Last system dissipated | Season ongoing |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Enrique |

| • Maximum winds | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 982 mbar (hPa; 29 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 5 |

| Total storms | 5 |

| Hurricanes | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 3 total |

| Total damage | Unknown |

| Related articles | |

The 2021 Pacific hurricane season is an ongoing event of the annual tropical cyclone season in the Northern Hemisphere. The season officially began on May 15 in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; both will end on November 30. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Pacific Ocean basin and are adopted by the convention. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year, as illustrated by the formation of Tropical Storm Andres on May 9. Andres was the earliest forming tropical storm in the northeastern Pacific proper (east of 140°W longitude) on record, surpassing Tropical Storm Adrian of 2017 by 12 hours.

Seasonal forecasts

| Record | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (1991–2020): | 15 | 8 | 4 | [1] | |

| Record high activity: | 1992: 27 | 2015: 16 | 2015: 11 | [2] | |

| Record low activity: | 2010: 8 | 2010: 3 | 2003: 0 | [2] | |

| Date | Source | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| May 12, 2021 | SMN | 14–20 | 7–10 | 4–5 | [3] |

| May 20, 2021 | NOAA | 12–18 | 5–10 | 2–5 | [4] |

| Area | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref | |

| Actual activity: | EPAC | 5 | 1 | 0 | |

| Actual activity: | CPAC | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Actual activity: | 5 | 1 | 0 | ||

On May 12, 2021, the Servicio Meteorológico Nacional issued its forecast for the season, predicting a total of 14–20 named storms, 7–10 hurricanes, and 4–5 major hurricanes to develop.[3] On May 20, 2021, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued their outlook, calling for a below-normal to near-normal season with 12–18 named storms, 5–10 hurricanes, 2–5 major hurricanes, and an accumulated cyclone energy index of 65% to 120% of the median. Factors they expected to reduce activity were near- or below-average sea surface temperatures across the eastern Pacific and the El Niño–Southern Oscillation remaining in the neutral phase, with the possibility of a La Niña developing.[4]

Seasonal summary

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index for the 2021 Pacific hurricane season, as of 15:00 UTC June 20, is 4.6375 units in the Eastern Pacific and 0 units in the Central Pacific. The total ACE in the basin is 4.6375 units.[nb 1] Broadly speaking, ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical or subtropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. It is only calculated for full advisories on specific tropical and subtropical systems reaching or exceeding wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h).

Although hurricane season in the eastern Pacific does not officially begin until May 15, and on June 1 in the central Pacific,[5] activity began early, with Tropical Storm Andres forming on May 9. However it was short-lived, dissipating after encountering unfavorable conditions after two days. After a pause in activity, Blanca formed, marking only the sixth time since 1949 that two tropical storms developed in the month of May, with the other years being 1956, 1984, 2007, 2012, and 2013. A week after Blanca dissipated, Carlos formed, but it stayed over open waters and never affected land. Dolores formed shortly after and peaked as a strong tropical storm before making landfall in Mexico, causing considerable damage.

Systems

Tropical Storm Andres

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 9 – May 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

On May 7, a low-pressure system formed several hundred miles southwest of the southern coast of Mexico and was forecast to move into more favorable conditions by the weekend.[6] By May 8, the disturbance's thunderstorms started to quickly organize,[7] and the system was designated as Tropical Depression One-E at 09:00 UTC on the next day. At the time, the system's center became well-defined and located east of a well organized mass of convection despite the negative impact of moderate west-southwesterly wind shear on the system.[8] According to scatterometer data and satellite estimates, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Andres six hours later, becoming the earliest named storm in the Northeast Pacific (east of 140°W) on record in the satellite era, breaking the previous record of Tropical Storm Adrian in 2017 by 12 hours.[9] However, Andres did not have any banding features, and its appearance became more ragged on satellite imagery as it moved into an area with increasingly hostile conditions.[10] Soon afterward, wind shear caused the storm's circulation to become elongated and its cloud tops to warm.[11] Andres weakened to a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC on May 10 as its center became devoid of convective activity and the remaining thunderstorms were displaced well to the east of the storm's center of circulation.[12] Andres subsequently degenerated into a remnant low at 15:00 UTC on May 11.[13]

The outer storms of Andres produced heavy rainfall in Southwestern Mexico.[14][15][16] Moisture from the storm caused intense rain and even a hailstorm as far east as the State of Mexico, including in the state's capital, Toluca.[16] Vehicles became stranded in floods, some small trees got knocked over, and about 50 houses were damaged by a flooding river.[17][18] 30 cars were also stranded in a flooded parking lot of a church in Metepec.[19]

Tropical Storm Blanca

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 30 – June 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

On May 24, the National Hurricane Center first noted an area of low pressure to develop south of the coast of Mexico for possible tropical cyclogenesis.[20] Four days later, a low-pressure area finally formed a couple of hundred kilometers south of the country.[21] The low was initially embedded within a large monsoon trough and was interacting with another system to its east. However, as it gradually moved west-northwestwards, the system became more organized and better defined, and by 21:00 UTC on May 30, was classified as Tropical Depression Two-E.[22] The depression continued to gradually become more symmetric, despite its displaced low- and mid-level circulations.[23] The next day, Two-E strengthened to a tropical storm and received the name Blanca.[24] A relatively compact cyclone, Blanca quickly gained strength throughout the day of May 31, reaching its peak intensity at 09:00 UTC on June 1 with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a pressure of 998 mb (29.47 inHg).[25] Shortly afterwards, vertical wind shear weakened Blanca as its low level circulation became partially exposed on satellite images later into the day.[26] Blanca continued to weaken on June 2 due to wind shear and the entrainment of dry, stable air into its circulation.[27] Blanca further weakened into a tropical depression later that day.[28] Blanca degenerated into a post-tropical cyclone early on June 4 as thunderstorm activity dissipated completely.[29]

Tropical Storm Carlos

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 12 – June 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

On June 2, the National Hurricane Center noted the possible development of a low-pressure area located several miles offshore the southwestern coast of Mexico in the next five days.[30] A day later, the low-pressure area formed and was located in favorable conditions.[31] On June 6, the NHC upgraded the low pressure chances of developing into a tropical cyclone to 90%, but the system lacked a well defined low level circulation.[32] However, on June 8, cyclogenesis was no longer expected as a result of limited thunderstorm activity due to dry air and strong wind shear.[33] On June 10, the low-pressure area began producing more thunderstorm activity and was once again monitored for possible cyclogenesis as it traversed favorable environmental conditions.[34] By 21:00 UTC on June 12, it had attained a compact low-level circulation with more developed convection, prompting the NHC to designate the disturbance Tropical Depression Three-E.[35] Six hours later, Three-E strengthened into a tropical storm and was given the name Carlos after satellite imagery indicated improved organization and convective banding on the system.[36] Carlos strengthened gradually throughout June 13, and reached peak intensity around 15:00 UTC with 50 mph (80 km/h) winds and a minimum pressure of 1000 millibars.[37] However, early on June 14, Carlos' organization began to degrade due to very dry air in its proximity and increasing wind shear.[38] Carlos weakened to a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC that day as most of its convection dissipated.[39] Carlos was almost devoid of convection apart from a small convective burst by the next day.[40] On June 16, Carlos degenerated into a remnant low as all of the convection dissipated due to dry air.[41]

Tropical Storm Dolores

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 18 – June 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 990 mbar (hPa) |

On June 15, the National Hurricane Center first marked the possible development of a low-pressure area located several miles offshore southwestern Mexico.[42] A day later, the low-pressure formed and was producing disorganized showers and thunderstorms. The disturbance was expected to move into conductive environmental conditions over the next couple of days.[43] On June 18 at 09:00 UTC, the NHC assessed it to have strengthened into Tropical Depression Four-E, after a scatterometer pass indicated a closed circulation alongside surrounding convection becoming more well-defined.[44] Six hours later, the storm's convection became even more pronounced, and the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Dolores as banding features became established.[45] On June 19 at 15:00 UTC, Dolores made landfall over the Michoacán-Colima border according to satellite imagery.[46] As it moved further inland, it rapidly weakened into a depression on June 20 at 03:00 UTC.[47] At 09:00 UTC on the same day, the NHC declared it as a remnant low as the system moved over mountainous terrain.[48]

Hurricane Enrique

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

Current storm status Category 1 hurricane (1-min mean) | |||

| |||

| As of: | 01:00 p.m. CDT (18:00 UTC) June 26 | ||

| Location: | 17°12′N 105°36′W / 17.2°N 105.6°W ± 25 nm About 230 mi (370 km) S of Cabo Corrientes, Mexico About 500 mi (805 km) SE of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico | ||

| Sustained winds: | 75 knots (85 mph; 140 km/h) (1-min mean) gusting to 85 knots (100 mph; 155 km/h) | ||

| Pressure: | 982 mbar (29.00 inHg) | ||

| Movement: | WNW at 7 knots (8 mph; 13 km/h) | ||

| See more detailed information. | |||

On June 20, NHC noted a possible formation of a low-pressure area near the south of Guatemala and Gulf of Tehuantepec.[49] On June 22, a tropical wave formed over Central America with satellite imagery indicating disorganized showers and thunderstorms.[50] With conductive environmental conditions, the system gradually organized and on June 25 at 09:00 UTC, the NHC assessed the system as a tropical storm, assigning the name Enrique.[51] Satellite imagery also revealed that the storm had developed a low-level circulation, with a scatterometer pass over the storm also showing that it was producing tropical storm-force winds to the southeast of the center.[52][51] The storm's structure had further improved six hours later, with prominent banding features to the south and east.[53] Later, a large convective burst developed over the storm.[54] Enrique continued to intensify throughout the day, with the NHC assessing the system to have strengthened into a category 1 hurricane by 09:00 UTC on June 26, after which the system possessed a well-defined central dense overcast and alongside persistent area of cold cloud tops.[55] An area of overshooting cloud tops signaled that the eyewall was developing.[56]

Current storm information

As of 10:00 a.m. CDT (15:00 UTC) June 26, Hurricane Enrique is located within 25 nautical miles of 17°06′N 105°18′W / 17.1°N 105.3°W, about 230 mi (370 km) south of Cabo Corrientes, Mexico, and about 500 mi (805 km) southeast of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. Maximum sustained winds are 65 knots (75 mph; 120 km/h), with gusts up to 85 knots (100 mph; 155 km/h). The minimum barometric pressure is 988 mbar (29.18 inHg), and the system is moving west-northwest at 7 knots (8 mph; 13 km/h).

For the latest official information, see:

- The NHC's latest public advisory on Hurricane Enrique

- The NHC's latest forecast advisory on Hurricane Enrique

- The NHC's latest forecast discussion on Hurricane Enrique

Watches and warnings

Template:HurricaneWarningsTable

Storm names

The following names will be used for named storms that form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean during 2021. Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization during the joint 44th Sessions of the RA IV Hurricane Committee in the spring of 2022. The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2027 season.[57] This is the same list used in the 2015 season, with the exception of the name Pamela, which replaced Patricia.

|

|

|

In wake of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, after the Greek alphabet was deemed too confusing to use, the WMO decided to end the use of the Greek alphabet as an auxiliary list. Therefore, beginning this season, if all 24 names above are used, subsequent storms will take names from a new supplemental naming list. The auxiliary list will be used if necessary in all seasons.[58]

For storms that form in the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility, encompassing the area between 140 degrees west and the International Date Line, all names are used in a series of four rotating lists.[59] The next four names that will be slated for use in 2021 are shown below.

|

|

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms and that have formed in the 2021 Pacific hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a tropical wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 2021 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andres | May 9 – 11 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1005 | Southwestern Mexico | None | None | [15] | ||

| Blanca | May 30 – June 4 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 998 | None | None | None | |||

| Carlos | June 12 – 16 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | None | None | None | |||

| Dolores | June 18 – 20 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 990 | Southwestern Mexico, Western Mexico | Unknown | 3 | [60][61] | ||

| Enrique | June 25 – Present | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 982 | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 5 systems | May 9 – Season ongoing | 85 (140) | 982 | Unknown | 3 | |||||

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2021

- Pacific hurricane

- 2021 Atlantic hurricane season

- 2021 Pacific typhoon season

- 2021 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2020–21, 2021–22

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2020–21, 2021–22

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2020–21, 2021–22

Notes

- ^ The totals represent the sum of the squares for every (sub)tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2021 Pacific hurricane season/ACE calcs.

References

- ^ "Background Information: East Pacific Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 20, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ a b National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 26, 2024). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2023". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Pronóstico para la Temporada de Ciclones Tropicales 2021". YouTube.com.

- ^ a b "NOAA 2021 Eastern Pacific Hurricane Season Outlook". Climate Prediction Center. May 20, 2021. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Dorst Neal. When is hurricane season? (Report). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ^ Robbie Berg (May 7, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Jack Beven (May 8, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Stacy R. Stewart (May 9, 2021). "Tropical Depression One-E Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Stacy R. Stewart (May 9, 2021). "Tropical Storm Andres Discussion Number 2". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Richard Pasch (May 9, 2021). "Tropical Storm Andres Discussion Number 3". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brad Reinhart; Richard Pasch (May 10, 2021). "Tropical Storm Andres Discussion Number 6". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Brad Reinhart; John Cangialosi (May 10, 2021). "Tropical Depression Andres Discussion Number 7". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Richard Pasch; Daniel Brown (May 11, 2021). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Andres Discussion Number 10". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Óscar Barrón (May 9, 2021). "Pronóstico del clima de hoy: se esperan lluvias por depresión tropical UNO-E del Pacífico". Debate (in Spanish). Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Juan Antonio Palma (May 7, 2021). "Tormentas y probable formación ciclónica para este fin de semana". Meteored.mx | Meteored (in Mexican Spanish). Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ a b "SE FORMA ANDRES!". Noticias Va de Nuez (in Spanish). May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "Tormenta inunda estacionamiento en Metepec; reportan afectaciones en Toluca". www.msn.com (in European Spanish). May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Tormenta de granizo en Toluca deja calles y casas inundadas". EL IMPARCIAL | Noticias de México y el mundo (in European Spanish). May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Se adelanta temporada de ciclones". El Heraldo de Aguascalientes (in Spanish). May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Andy S. Latto (May 24, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ John Cangialosi (May 28, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Stacy R. Stewart (May 30, 2021). "Tropical Depression Two-E Advisory Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Daniel Brown (May 30, 2021). "Tropical Depression Two-E Discussion Number 2". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Stacy R. Stewart (May 31, 2021). "Tropical Storm Blanca Advisory Number 5". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brad Reinhart; Jack Beven (June 1, 2021). "Tropical Storm Blanca Forecast Discussion Number 7". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Philippe Papin; Stacy R. Stewart (June 1, 2021). "Tropical Storm Blanca Forecast Discussion Number 8". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Philippe Papin; Stacy R. Stewart (June 2, 2021). "Tropical Storm Blanca Forecast Discussion Number 12". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Philippe Papin; Stacy R. Stewart (June 2, 2021). "Tropical Depression Blanca Discussion Number 13". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Andrew Latto (June 4, 2021). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Blanca Discussion Number 19". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brad Reinhart; Jack Beven (June 2, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ John Cangialosi (June 3, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ John Cangialosi (June 6, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brad Reinhart; Richard Pasch (June 8, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brad Reinhart; Jack Beven (June 10, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Andrew Latto (June 12, 2021). "Tropical Depression Three-E Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Philippe Papin; Richard Pasch (June 12, 2021). "Tropical Storm Carlos Discussion Number 2". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Andrew Latto (June 13, 2021). "Tropical Storm Carlos Discussion Number 4". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Stacy R. Stewart (June 14, 2021). "Tropical Storm Carlos Discussion Number 7". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Andrew Latto (June 14, 2021). "Tropical Depression Carlos Discussion Number 9". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brad Reinhart; Richard Pasch (June 14, 2021). "Tropical Depression Carlos Discussion Number 10". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Robbie Berg (June 16, 2021). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Carlos Advisory Number 16". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Andy Latto (June 18, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Robbie Berg (June 18, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Philippe Papin; Eric Blake (June 18, 2021). "Tropical Depression Four-E Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Robbie Berg (June 18, 2021). "Tropical Storm Dolores Discussion Number 2". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Robbie Berg (June 19, 2021). "Tropical Storm Dolores Discussion Number 6". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Andrew Latto (June 19, 2021). "Tropical Storm Dolores Discussion Number 8". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Brad Reinhart; Eric Blake (June 20, 2021). "Remnants Of Dolores Discussion Number 9". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Stacy R. Stewart (June 20, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Robbie Berg (June 22, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Jack Beven (June 25, 2021). "Five-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Jack Beven (June 25, 2021). "Tropical Storm Enrique Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Philippe Papin; John Cangialosi (June 25, 2021). "Tropical Storm Enrique Discussion Number 2". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Philippe Papin; John Cangialosi (June 25, 2021). "Tropical Storm Enrique Discussion Number 3". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Jack Beven (June 26, 2021). "Hurricane Enrique Forecast Discussion Number 5". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ "Hurricane ENRIQUE". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Names". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Hurricane Committee retires tropical cyclone names and ends the use of Greek alphabet". public.wmo.int. World Meteorological Organization. March 17, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ "Pacific Tropical Cyclone Names 2016–2021". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 12, 2016. Archived from the original (PHP) on December 30, 2016.

- ^ "Dolores se disipa en México tras dejar tres muertes por tormentas eléctricas". www.efe.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-06-21.

- ^ "Tormenta tropical 'Dolores' deja un muerto a su paso por Jalisco". Noticieros Televisa (in Mexican Spanish). 2021-06-21. Retrieved 2021-06-21.