Feudalism

Feudalism refers to a general set of reciprocal legal and military obligations among the warrior nobility of Europe during the Middle Ages, revolving around the three key concepts of lords, vassals, and fiefs.

Defining feudalism requires many qualifiers because there is no broadly accepted agreement of what it means. For one to begin to understand feudalism, a working definition is desirable. The definition described in this article is the most senior and classic definition and is still subscribed to by many historians.

However, other definitions of feudalism exist. Since at least the 1960s, many medieval historians have included a broader social aspect, adding the peasantry bonds of Manorialism, referred to as a "feudal society". Still others, since the 1970s, have re-examined the evidence and concluded that feudalism is an unworkable term and should be removed entirely from scholarly and educational discussion (see Revolt against the term feudalism), or at least only used with severe qualification and warning.

Outside of a European context, the concept of feudalism is normally only used by analogy (called semi-feudal), most often in discussions of Japan under the shoguns, and, sometimes, medieval and Gondarine Ethiopia. However, some have taken the feudalism analogy further, seeing it in places as diverse as Ancient Egypt, Parthian empire, India, to the American South of the nineteenth century. [1]

Etymology

The first known use of the term feudal was in the 17th century (1614), when the system it was purported to describe was rapidly vanishing or gone entirely. No writer in the period in which feudalism was supposed to have flourished ever used the word itself. It was a pejorative word used to describe any law or custom that was seen as unfair or out-dated. Most of these laws and customs were related in some way to the medieval institution of the fief (Latin: feodum, a word which first appears on a Frankish charter dated 884), and thus lumped together under this single term. "Feudalism" comes from the French féodalisme, a word coined during the French Revolution. The English novelist Tobias Smollett (1721-1771) made fun of the term in his novel Humphry Clinker (1771): "Every peculiarity of policy, custom and even temperament is traced to this [Feudal] origin.. I expect to see the use of trunk-hose and buttered ale ascribed to the influence of the feudal system."

What is feudalism?

- See also Feudal society and Examples of feudalism

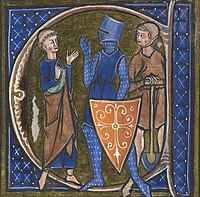

Three primary elements characterized feudalism: lords, vassals and fiefs; the structure of feudalism can be seen in how these three elements fit together. A lord was a noble who owned land, a vassal was a person who was granted possession of the land by the lord, and the land was known as a fief. In exchange for the fief, the vassal would provide military service to the lord. The obligations and relations between lord, vassal and fief form the basis of feudalism.

Lords, vassals, and fiefs

Before a lord could grant land (a fief) to someone, he had to make that person a vassal. This was done at a formal and symbolic ceremony called a commendation ceremony comprised of the two-part act of homage and oath of fealty. During homage, the vassal would promise to fight for the lord at his command. Fealty comes from the Latin fidelitas, or faithfulness; the oath of fealty is thus a promise that the vassal will be faithful to the lord. Once the commendation was complete, the lord and vassal were now in a feudal relationship with agreed-upon mutual obligations to one another.

The lord's principal obligation was to grant a fief, or its revenues, to the vassal; the fief is the primary reason the vassal chose to enter into the relationship. In addition, the lord sometimes had to fulfill other obligations to the vassal and fief. One of those obligations was its maintenance. Since the lord had not given the land away, only loaned it, it was still the lord's responsibility to maintain the land, while the vassal had the right to collect revenues generated from it. Another obligation that the lord had to fulfill was to protect the land and the vassal from harm.

The vassal's principal obligation to the lord was to provide "aid", or military service. Using whatever equipment the vassal could obtain by virtue of the revenues from the fief, the vassal was responsible to answer to calls to military service on behalf of the lord. This security of military help was the primary reason the lord entered into the feudal relationship. In addition, the vassal sometimes had to fulfill other obligations to the lord. One of those obligations was to provide the lord with "counsel", so that if the lord faced a major decision, such as whether or not to go to war, he would summon all his vassals and hold a council. The vassal may have been required to provide a certain amount of his farm's yield to his lord. The vassal was also sometimes required to grind his wheat and bake his bread in the mills and ovens owned and taxed by his lord.

The land-holding relationships of feudalism revolved around the fief. Depending on the power of the granting lord, grants could range in size from a small farm to a much larger area of land. The size of fiefs was described in irregular terms quite different from modern area terms; see medieval land terms. The lord-vassal relationship was not restricted to members of the laity; bishops and abbots, for example, were also capable of acting as lords.

There were thus different 'levels' of lordship and vassaldom. The King was a lord who loaned fiefs to aristocrats, who were his vassals. Meanwhile the aristocrats were in turn lords to their own vassals, the peasants who worked on their land. Ultimately, the Emperor was a lord who loaned fiefs to Kings, who were his vassals. This traditionally formed the basis of a 'universal monarchy' as an imperial alliance and a world order.

Examples of feudalism

- Main article: Examples of feudalism

Examples of feudalism are helpful to understand feudal society because feudalism was practiced in many different ways, depending on location and time period. A high-level encompassing conceptual definition will not always provide the reader with the more practical understanding available from historical examples.

History of the term "feudalism"

In order to better understand what the term feudalism means, it is helpful to see how it was defined and how it has been used since its seventeenth century creation.

Invention of the concept of feudalism

The word feudalism was not a medieval term. It was invented by French and English lawyers in the 17th to describe certain traditional obligations between members of the warrior aristocracy. The term first reached a popular and wide audience in Montesquieu's De L'Esprit des Lois (The Spirit of the Laws) in 1748. Since then it has been redefined and used by many different people in different ways.

The term feudalism has been used by different political philosophers and thinkers throughout history.

Enlightenment thinkers on feudalism

In the 18th century, writers of the Enlightment wrote about feudalism in order to denigrate the antiquated system of the Ancien Régime, or French monarchy. This was the Age of Enlightenment when Reason was king and the Middle Ages was painted as the "Dark Ages". Enlightenment authors generally mocked and ridiculed anything from the "Dark Ages" including Feudalism, projecting its negative characteristics on the current French monarchy as a means of political gain.

Karl Marx on feudalism

Quite similar to the French revolutionaries, Karl Marx also used the term feudalism for political ends. In the nineteenth century, Marx described feudalism as the economic situation coming before the inevitable rise of capitalism. For Marx, what defined feudalism was that the power of the ruling class (the aristocracy) rested on their control of the farmable lands, leading to a class society based upon the exploitation of the peasants who farm these lands, typically under serfdom. “The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist.” (The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), chapter 2). Marx thus considered feudalism with a purely economic model. Marxian theorists have been discussing feudalism for the past 150 years - an extensive and well known debate over feudalism and capitalism occurred between the noted Marxian economist Paul Sweezy and his British colleague Maurice Dobb. See also mode of production.

Historians on feudalism

The term feudalism is, among medieval historians, one of the most widely debated concepts. There exist many definitions of feudalism and indeed some have revolted against it, saying the term should not be used at all.

Debating the origins of English feudalism

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century historians John Horace Round and Frederic William Maitland, who focused on medieval Britain, arrived at different conclusions as to the character of English society prior to the start of Norman rule in 1066. Round argued for a Norman import of feudalism, while Maitland contended that the fundamentals were already in place in Britain. The debate continues to this day.

Ganshof and the classic view of feudalism

A historian whose concept of feudalism remains highly influential in the 20th century is François-Louis Ganshof, who belongs to a pre-Second World War generation. Ganshof defines feudalism from a narrow legal and military perspective, arguing that feudal relationships existed only within the medieval nobility itself. Ganshof articulated this concept in Feudalism (1944). His classic definition of feudalism is the most widely known today and also the easiest to understand: simply put, when a lord granted a fief to a vassal, the vassal provided military service in return.

Marc Bloch and sociological views of feudalism

One of Ganshof's contemporaries, a French historian named Marc Bloch, is arguably the most influential medieval historian of the twentieth century. Bloch approached feudalism not so much from a legal and military point of view but from a sociological one. He developed his ideas in Feudal Society (1939). Bloch conceived of feudalism as a type of society that was not limited solely to the nobility. Like Ganshof, he recognized that there was a hierarchal relationship between lords and vassals, but saw as well a similar relationship obtaining between lords and peasants.

It is this radical notion that peasants were part of the feudal relationship that sets Bloch apart from his peers. While the vassal performed military service in exchange for the fief, the peasant performed physical labour in return for protection. Both are a form of feudal relationship. According to Bloch, other elements of society can be seen in feudal terms; all the aspects of life were centered on "lordship", and so we can speak usefully of a feudal church structure, a feudal courtly (and anti-courtly) literature, a feudal economy. (See Feudal society.)

Revolt against the term feudalism

In 1974, U.S. historian Elizabeth A.R. Brown, in "The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe" (American Historical Review 79), rejecting the label of feudalism as an anachronistic construct that imparts a false sense of uniformity to the concept. She noted the many different, contradictory definitions of feudalism in circulation and argued that, in the absence of any accepted definition, feudalism is a construct with no basis in medieval reality, an invention of modern historians read back "tyrannically" into the historical record. Supporters of Brown have gone so far as to suggest that the term should be expunged from history textbooks and lectures on medieval history entirely. In Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted (1994), Susan Reynolds expanded upon Brown's original thesis. Although some of her contemporaries questioned Reynolds' methodology, her thesis has received support from other historians. Note that Reynolds does not object to the Marxist use of 'feudalism'.

History of feudalism

Early forms of feudalism in Europe

Vassalage agreements similar to what would later develop into legalized medieval feudalism originated from the blending of ancient Roman and Germanic traditions. The Romans had a custom of patronage whereby a stronger patron would provide protection to a weaker client in exchange for gifts, political support and prestige. In the countryside of the later Empire, the reforms of Diocletian and his successors attempted to put certain jobs, notably farming, on an hereditary basis. As governmental authority declined and rural lawlessness (such as that of the Bagaudae) increased, these farmers were increasingly forced to rely upon the protection of the local landowner, and a nexus of interdependency was created: the landowners depended upon the peasants for labour, and the peasants upon the landowners for protection.

Ancient Germans had a custom of equality among warriors, an elected leader who kept the majority of the wealth (land) and who distributed it to members of the group in return for loyalty.

Decline of feudalism

Feudalism had begun as a contract, the exchange of land tenure for military service. Over time, as lords could no longer provide new lands to their vassals, nor enforce their right to reassign lands which had become de facto hereditary property, feudalism became less tenable as a working relationship. By the thirteenth century, Europe's economy was involved in a transformation from a mostly agrarian system to one that was increasingly money-based and mixed. The Hundred Year's War instigated this gradual transformation as soldier's pay became amounts of gold instead of land. Therefore, it was much easier for a monarch to pay low-class citizens in mineral wealth, and many more were recruited and trained, putting more gold into circulation, thus undermining the land-based feudalism. Land ownership was still an important source of income, and still defined social status, but even wealthy nobles wanted more liquid assets, whether for luxury goods or to provide for wars. This corruption of the form is often referred to as "bastard feudalism". A noble vassal was expected to deal with most local issues and could not always expect help from a distant king. The nobles were independent and often unwilling to cooperate for a greater cause (military service). By the end of the Middle Ages, the kings were seeking a way to become independent of willful nobles, especially for military support. The kings first hired mercenaries and later created standing national armies.

Historian J. J. Bagley notes that the fourteenth century

- "marked the end of the true feudal age and began paving the way for strong monarchies, nation states, and national wars of the sixteenth century. Much fourteenth century feudalism had become artificial and self-conscious. Already men were finding it a little curious. It was acquiring an antiquarian interest and losing its usefulness. It was ceasing to belong to the real world of practical living."

Questioning feudalism

Did feudalism exist?

The following are historical examples that call into question the traditional use of the term feudalism.

Extant sources reveal that the early Carolingians had vassals, as did other leading men in the kingdom. This relationship did become more and more standardized over the next two centuries, but there were differences in function and practice in different locations. For example, in the German kingdoms that replaced the kingdom of Eastern Francia, as well as in some Slavic kingdoms, the feudal relationship was arguably more closely tied to the rise of Serfdom, a system that tied peasants to the land.

Moreover, the evolution of the Holy Roman Empire greatly affected the history of the feudal relationship in central Europe. If one follows long-accepted feudalism models, one might believe that there was a clear hierarchy from Emperor to lesser rulers, be they kings, dukes, princes, or margraves. These models are patently untrue: the Holy Roman Emperor was elected by a group of seven magnates, three of whom were princes of the church, who in theory could not swear allegiance to any secular lord.

The French kingdoms also seem to provide clear proof that the models are accurate, until we take into consideration the fact that, when Rollo of Normandy kneeled to pay homage to Charles the Simple in return for the Duchy of Normandy, accounts tell us that he knocked the king on his rump as he rose, demonstrating his view that the bond was only as strong as the lord - in this case, not strong at all. Clearly, it was possible for 'vassals' to openly disparage feudal relationships.

The autonomy with which the Normans ruled their duchy supports the view that, despite any legal "feudal" relationship, the Normans did as they pleased. In the case of their own leadership, however, the Normans utilized the feudal relationship to bind their followers to them. It was the influence of the Norman invaders which strengthened and to some extent institutionalized the feudal relationship in England after the Norman Conquest.

Since we do not use the medieval term vassalage how are we to use the term feudalism? Though it is sometimes used indiscriminately to encompass all reciprocal obligations of support and loyalty in the place of unconditional tenure of position, jurisdiction or land, the term is restricted by most historians to the exchange of specifically voluntary and personal undertakings, to the exclusion of involuntary obligations attached to tenure of "unfree" land: the latter are considered to be rather an aspect of Manorialism, an element of feudal society but not of feudalism proper.

Cautions on use of term "feudalism"

"Feudalism" and related terms should be approached and used with considerable caution owing to the range of meanings associated with the term. A cautious historian like Fernand Braudel sets "feudalism" in quotes in applying it in wider social and economic contexts, such as "the seventeenth century, when much of America was being 'feudalized' as the great haciendas appeared" (The Perspective of the World, 1984, p. 403).

Medieval societies never described themselves as "feudal". Though used in popular parlance to represent all voluntary or customary bonds in medieval society, or a social order in which civil and military power is exercised under private contractual arrangements, the term is best considered appropriate only to the voluntary, personal undertakings binding lords and free men to protection in return for support which characterised the administrative and military order.

Other feudal-like systems

Other feudal-like land tenure systems have existed, and continue to exist, in different parts of the world.

Notes

- Template:FnbPhilip Daileader (2001). "Feudalism". The High Middle Ages. The Teaching Company. ISBN 1-56585-827-1

External links

- "Feudalism". In Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

- "Feudalism?", by Paul Halsall from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook, history of the term.

- "Feudalism", by Gerhard Rempel, Western New England College

- "Feudalism, Self-employment, and the 1949 Chinese Revolution", by Satya J. Gabriel, Mount Holyoke College

Bibliography

- Marc Bloch, Feudal Society. Tr. L.A. Manyon. Two volumes. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1961 ISBN 0-226-05979-0

- Francois-Lois Ganshof, Feudalism. Tr Philip Grierson. New York: Harper and Row, 1964.

- Jean-Pierre Poly and Eric Bournazel, The Feudal Transformation, 900-1200., Tr. Caroline Higgitt. New York and London: Holmes and Meier, 1991.

- Susan Reynolds, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-19-820648-8

- Normon E. Cantor. Inventing the Middle Ages: The Lives, Works, and Ideas of the Great Medievalists of the Twentieth century. Quill, 1991.

- Alain Guerreau, L'avenir d'un passé incertain. Paris: Le Seuil, 2001. (complete history of the meaning of the term).