Zettelkasten

The zettelkasten (German: "slip box", plural zettelkästen) is a system of note-taking and personal knowledge management used in research and study.[1]

System

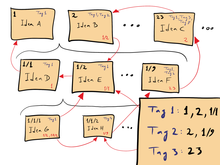

A zettelkasten consists of many individual notes with ideas and other short pieces of information that are taken down as they occur or are acquired.[2] The notes may be numbered hierarchically so that new notes may be inserted at the appropriate place, and contain metadata to allow the note-taker to associate notes with each other. For example, notes may contain subject headings or tags that describe key aspects of the note, and they may reference other notes. The numbering, metadata, format and structure of the notes is subject to variation depending on the specific method employed.[2]

A zettelkasten may be created and used in a digital format, sometimes using personal knowledge management software. But it can be and has long been done on paper using index cards.

The system not only allows a researcher to store and retrieve information related to their research, but has also been used to enhance creativity.[2]

History

In the form of paper index cards in boxes, the zettelkasten has long been used by individual researchers and by organizations to manage information, including the specialized form of the library catalog. Coming from a commonplace book tradition,[3] Conrad Gessner (1516–1565) invented his own method of organization in which the individual notes could be rearranged at any time. In retrospect, his recommendation of gluing slips onto bound sheets[4][5] was an innovation in moving from commonplace books to index cards as a form factor.

The first early modern card index was designed by 17th-century English inventor Thomas Harrison (c. 1640s). Harrison's manuscript on the "ark of studies"[6] (Arca studiorum) describes a small cabinet that allows users to excerpt books and file their notes in a specific order by attaching pieces of paper to metal hooks labeled by subject headings.[7] Harrison's system was edited and improved by Vincent Placcius in his well-known handbook on excerpting methods (De arte excerpendi, 1689).[8] Librarian and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was known to have relied on Harrison's invention in at least one of his research projects.[8]

In 1767, Carl Linnaeus used "little paper slips of a standard size" to record information for his research.[9] Over 1,000 of Linnaeus's precursors to the modern index card containing information collected from books and other publications and measuring five by three inches are housed at the Linnean Society of London.[7]

Later in his own commonplace, under the heading "My way of collecting materials for future writings" (translated), Johann Jacob Moser (1701–1785) described the algorithms with which he filled his "card boxes".[2]

The 1796 idyll Leben des Quintus Fixlein by novelist Jean Paul is structured according to the zettelkasten in which the protagonist keeps his autobiography.[2] Jean Paul ultimately assembled 12,000 paper scraps into his commonplace books over the course of his lifetime, but died in 1825, almost a century before the advent of standardized note cards or box systems which later made it easier to store and organize them.[10]

Antonin Sertillanges' book The Intellectual Life (1921) outlines in Chapter 7 a version of the zettelkasten method, although he neither uses the German name nor gives the method any specific name.[11] The book was published in French and English in more than 45 editions over the span of 60 years.[12] In it, Sertillanges recommends taking notes on slips of "strong paper of a uniform size" either self made with a paper cutter or by "special firms that will spare you the trouble, providing slips of every size and color as well as the necessary boxes and accessories". He also recommends a "certain number of tagged slips, guide-cards, so as to number each category visibly after having numbered each slip, in the corner or in the middle". He goes on to suggest creating a catalog or index of subjects with divisions and subdivisions and recommends the "very ingenious system", the decimal system, for organizing one's research. For the details of this he refers the reader to Organization of Intellectual Work: Practical Recipes for Use by Students of All Faculties and Workers by Paul Chavigny.[13] Sertillanges recommends against the previous patterns seen with commonplace books where one does note taking in books or on slips of paper which might be pasted into books as they don't "easily allow classification" or "readily lend themselves to use at the moment of writing".[11]

Philosopher and intellectual historian Hans Blumenberg (1920–1996) compiled more than 30,000 cards into his zettelkasten, which now occupy thirty-two conservation boxes at the German Literature Archive in Marbach. Blumenberg was inspired by the previous notetaking work and output of Georg Christoph Lichtenberg who used waste books or sudelbücher as he called them.[10]

One researcher famous for his extensive use of the method was the sociologist Niklas Luhmann (1927–1998). Luhmann built up a zettelkasten of some 90,000 index cards for his research, and credited it for enabling his extraordinarily prolific writing (including over 70 books and 400 scholarly articles).[14] He linked the cards together by assigning each a unique index number based on a branching hierarchy.[15] These index cards were digitized and made available online in 2019.[16] Luhmann described the zettelkasten as part of his research into systems theory in the essay "Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen".[17][18]

Other well known zettelkasten users include Arno Schmidt, Walter Kempowski, Friedrich Kittler, and Aby Warburg, whose works along with those of Paul, Blumenberg, and Luhmann appeared in the 2013 exhibition "Zettelkästen. Machines of Fantasy" at the Museum of Modern Literature, Marbach am Neckar.[1]

German writer Michael Ende kept a zettelkasten, and in 1994, a year prior to his death, he published Michael Endes Zettelkasten: Skizzen und Notizen (translation: Michael Ende's File-card Box: Drafts and Notes), an anthology of some of his writing as well as observations and aphorisms from his card file.[19]

While not referred to specifically as zettelkasten by their non-German speaking users, there is a tradition of keeping similar notes in a commonplace book–like tradition in other countries. Twentieth-century American comedians Phyllis Diller (with 52,000 3×5-inch index cards),[20][21] Joan Rivers (over a million 3×5-inch index cards),[22] Bob Hope (85,000 pages in files),[23] and George Carlin (paper notes in folders)[24] were known for keeping joke or gag files throughout their careers. They often compiled their notes from scraps of paper, receipts, laundry lists, and matchbooks which served the function of waste books. U.S. president Ronald Reagan kept punchlines for speeches in a card collection.[25]

In the creation of the Great Books of the Western World (1952), which also includes A Syntopicon, Mortimer J. Adler and many collaborators created a large shared collection of tagged and indexed cards to collate the ideas and information for their series.[26][27]

Anne Lamott devotes an entire chapter to Index Cards in her book 'Bird by Bird'[28] and Kate Grenville indicates that screenwriters are known to use index cards to help organise their scripts in a chapter devoted to using 'piles' of notes as part of the writing process.[29]

Literary references

- Jean Paul's idyll The Life of Quintus Fixlein (1796) has the subtitle as Drawn from Fifteen Boxes of Paper Slips.[2][30]

- In chapter two of Robert M. Pirsig's philosophical novel Lila: An Inquiry into Morals (1991), the main character describes an index card system of notes he's keeping for a book. While the German word zettelkasten isn't used, the descriptor "slips" is used repeatedly (as opposed to index card which appears four times) and the system has the general form and function of a zettelkasten as commonly used by writers.

See also

References

- ^ a b Gfrereis, Heike; Strittmatter, Ellen (2013). Zettelkästen. Maschinen der Phantasie. Marbacher Kataloge (in German). Vol. 66. Marbach am Neckar: Deutsche Schillerges. ISBN 978-3-937384-83-2. OCLC 835530478.

Der Zettelkasten ist die leibgewordene und vordigitale Variante dieser Phantasiemaschine: Lesefrüchte und Schreibeinfälle werden hier gesammelt und einsortiert, vernetzt und verschachtelt und – durch Glücksaufschläge, Buchstaben- oder Zahlencodes – immer wieder in neue Zusammenhänge gebracht: -Es- denkt und schreibt.

- ^ a b c d e f Haarkötter, Hektor. "'Alles Wesentliche findet sich im Zettelkasten'". heise online (in German). Archived from the original on 2020-07-15. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- ^ Havens, Earle (2001). Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century. New Haven: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University. pp. 34–35. ISBN 9780845731376. OCLC 47767194.

- ^ Zedelmaier, Helmut. "Christoph Just Udenius and the German ars excerpendi around 1700: On the Flourishing and Disappearance of a Pedagogical Genre". In Cevolini, Alberto (ed.). Forgetting Machines: Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe. Library of the written word. Vol. 53. Leiden; Boston: Brill. p. 102. doi:10.1163/9789004325258_005. ISBN 9789004278462. OCLC 951955805.

His [Hans Blumenbach's] example is the sixteenth-century Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner, who recommended gluing slips onto bound sheets.

- ^ Blair, Ann M. (2010). Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 212–225. doi:10.12987/9780300168495. ISBN 9780300112511. JSTOR j.ctt1nptsm. OCLC 601347978.

- ^ Harrison, Thomas (2017). Cevolini, Alberto (ed.). The Ark of Studies. De diversis artibus. Vol. 102. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. ISBN 9782503575230. OCLC 1004589834.

- ^ a b Blei, Daniela (2017-12-01). "How the Index Card Cataloged the World". The Atlantic. The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2021-07-04. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2021-05-08 suggested (help) - ^ a b Malcolm, Noel (September 2004). "Thomas Harrison and his 'ark of studies': an episode in the history of the organization of knowledge". The Seventeenth Century. 19 (2): 196–232 (220–221). doi:10.1080/0268117X.2004.10555543.

- ^ Müller-Wille, Staffan; Charmantier, Isabelle (March 2012). "Natural history and information overload: The case of Linnaeus". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 43 (1): Pages 4–15. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2011.10.021. PMC 3878424. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- ^ a b Helbig, Daniela K. "Ruminant machines: a twentieth-century episode in the material history of ideas". Journal of the History of Ideas Blog. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b Antonin, Sertillanges (1948). The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods. Translated by Ryan, Mary. Westminster, Maryland: The Newman Press. pp. 186–198. OCLC 6033719. Translated from the 1934 new French edition.

- ^ "Sertillanges, A.-D 1863-1948". WorldCat. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Chavigny, Paul (1918). Organisation du travail intellectuel: recettes pratiques à l'usage des étudiants de toutes les facultés et de tous les travailleurs (in French). Paris: Delagrave. OCLC 489977122.

- ^ Schmidt, Johannes. "Niklas Luhmann's Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine" (PDF). In Cevolini, Alberto (ed.). Forgetting Machines: Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe. Leiden; Boston: Brill. pp. 289–311. doi:10.1163/9789004325258_014. ISBN 9789004278462. OCLC 951955805. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-11-27. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- ^ Beaudoin-Zapier, Jack (2 August 2020). "This simple but powerful analog method will rocket your productivity". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Noack, Pit. "Missing Link: Luhmanns Denkmaschine endlich im Netz". heise online (in German). Archived from the original on 2020-07-12. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- ^ Luhmann, Niklas. "Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen. Ein Erfahrungsbericht", in: André Kieserling (ed.), Universität als Milieu. Kleine Schriften, Haux, Bielefeld 1992 (essay originally published 1981), ISBN 3-925471-13-8, p. 53–61; translated in: "Communicating with Slip Boxes". luhmann.surge.sh. Archived from the original on 2020-06-17. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- ^ Cevolini, Alberto (October 2018). "Where does Niklas Luhmann's card index come from?". Erudition and the Republic of Letters. 3 (4): 390–420. doi:10.1163/24055069-00304002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Ende, Michael (1994). Michael Endes Zettelkasten: Skizzen & Notizen. Stuttgart: Weitbrecht. ISBN 352271380X. OCLC 30643329.

- ^ "Transcribing The Phyllis Diller Gag File". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ BredenbeckCorp, Hanna. "Help us transcribe Phyllis Diller's jokes—and enjoy some laughs along the way!". National Museum of American History. March 1, 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "The Joan Rivers Archives: An exclusive look inside the lady's library-esque joke bank". GQ. Condé Nast Inc. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Bob Hope and American Variety: Joke File". Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (2017-09-29). "Discover George Carlin's Foolproof System for Organizing Ideas". Time. Time Inc. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Page, Susan (2011-05-08). "Ronald Reagan's note card collection being published". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2013-09-01. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ Beam, Alex (2008-11-04). A Great Idea at the Time: The Rise, Fall, and Curious Afterlife of the Great Books. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1586484873. OCLC 191926328.

- ^ Campbell, James (2008-11-14). "Heavy Reading". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Lamott, Anne (2008). "Index Cards". bird by bird. Carlton North, Victoria, Australia: Scribe. pp. 133–144. ISBN 978-1-921372-47-6.

- ^ Grenville, Kate (2010). "Sorting Through". The Writing Book. Crows Nest, NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-74237-388-1.

- ^ Paul, Jean (2013) [1796]. Leben des Quintus Fixlein, aus funfzehn Zettelkästen gezogen. Nebst einem Mustheil und einigen Jus de tablette. Geschichte meiner Vorrede zur zweiten Auflage des Quintus Fixlein. Werke: historisch-kritische Ausgabe (in German). Vol. VI, 1. Berlin: de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110303711. ISBN 9783484109179. OCLC 881295864.