Enheduanna

Enheduanna | |

|---|---|

Enheduanna, high priestess of Nanna (c. 23rd century BCE) | |

| Occupation | EN priestess |

| Language | Old Sumerian |

| Nationality | Akkadian Empire |

| Genre | Hymn |

| Subject | Nanna, Inanna |

| Notable works | Exaltation of Inanna Temple Hymns |

| Relatives | Sargon of Akkad (father) |

Enheduanna (Sumerian: 𒂗𒃶𒌌𒀭𒈾,[1] also transliterated as Enheduana, En-hedu-ana, or variants) was the EN priestess of the moon god Nanna (Sīn) in the Sumerian city-state of Ur in the reign of her father, Sargon of Akkad. She was likely appointed by her father as the leader of the religious cult at Ur to cement ties between the Akkadian religion of her father and the native Sumerian religion.

Enheduanna has been celebrated as the earliest known named author in world history, as a number of works in Sumerian literature, such as the Exaltation of Inanna feature her as the first person narrator, and other works, such as the Sumerian Temple Hymns may identify her as their author. However, there is considerable debate among modern Assyriologists based on linguistic and archaeological grounds as to whether or not she actually wrote or composed any of the rediscovered works that have been attributed to her. Additionally, the only manuscripts of the works attributed to her were written by scribes in the First Babylonian Empire six centuries after she lived, written in a more recent dialect of the Sumerian language than she would have spoken. These scribes may have attributed these works to her as part of the legendary narratives of the dynasty of Sargon of Akkad in later Babylonian traditions.

The cultural memory of Enheduanna and the works attributed to her were lost some time after the end of the First Babylonian Empire. Enheduanna's existence was first rediscovered by modern archaeology in 1927, when Sir Leonard Wooley excavated the Giparu in the ancient city of Ur and found an alabaster disk with her name, association with Sargon of Akkad, and occupation inscribed on the reverse. References to her name were then later discovered in excavated works of Sumerian literature, which initiated investigation into her potential authorship of those works. Enheduanna's archaeological rediscovery has attracted a considerable amount of attention and scholarly debate in modern times related to her potential attribution as the first known named author. She has also received considerable attention in feminism, and the works attributed to her have also been studied as an early progenitor of classical rhetoric. English translations of her works have also inspired a number of literary adaptations and representations.

Background

Enheduanna's father[2] was Sargon of Akkad, founder of the Akkadian empire. In a surviving inscription[3] Sargon styles himself "Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer (mashkim) of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed (guda) of Anu, king of the land [Mesopotamia], governor (ensi) of Enlil". The inscription celebrates the conquest of Uruk and the defeat of Lugalzagesi, whom Sargon brought "in a collar to the gate of Enlil"[3][4] Sargon, king of Akkad, overseer of Inanna, king of Kish, anointed of Anu, king of the land, governor of Enlil: he defeated the city of Uruk and tore down its walls, in the battle of Uruk he won, took Lugalzagesi king of Uruk in the course of the battle, and led him in a collar to the gate of Enlil.[5] Sargon then conquered Ur and "laid waste" the territory from Lagash to the sea,[6] ultimately conquering at least 34 cities in total.

Having conquered Ur, Irene J. Winter states that Sargon likely sought to "consolidate the Akkadian dynasty's links with the traditional Sumerian past in the important cult and political center of Ur" by appointing Enheduanna to an important position in the native Sumerian moon god cult. Winter states that is likely that the position she was appointed to already existed beforehand, and that her appointment to this role, and the attribution to Nanna would have helped her forge a syncreticism between the Sumerian religion and the Semitic religion. After Enheduanna, the role of high priestess continued to be held by members of the royal family. Joan Goodnick Westenholz[7] suggests that the role of high priestess appears to have held a similar level of honor to that of a king; as the high priestess of Nanna, Enheduanna would have served as the embodiment of Ningal, spouse of Nanna, which would have given her actions divine authority.[8] However, although the Giparu in Ur where the en priestess of Nanna worshipped has been extensively studied by archaeologists, we have no definitive information about what their duties were.[9]

Archaeological rediscovery

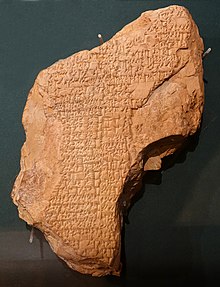

In 1927, as part of excavations at Ur, British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley discovered an alabaster disk shattered into several pieces, which has since been reconstructed. The reverse side of the disk identifies Enheduanna as the wife of Nanna and daughter of Sargon of Akkad. The front side shows the high priestess standing in worship as a nude male figure pours a libation.[10] Irene Winter states that "given the placement and attention to detail" of the central figure, "she has been identified as Enheduanna" [11] Two seals bearing her name, belonging to her servants and dating to the Sargonic period, have been excavated at the Giparu at Ur. [12]

Two of the works attributed to Enheduanna, "The Exaltation of Inanna" and "Inanna and Ebih" have survived in numerous manuscripts[13] due to their presence in the Decad, an advanced scribal curriculum in the First Babylonian Empire of the 18th and 17th centuries BCE. Black[14] et al. suggest that "perhaps Enheduanna has survived in scribal literature... due to the "continuing fascination with the dynasty of her father Sargon of Akkad".

Attributed works

The first person to connect the disk and seals with literary works excavated in Nippur was Adam Falkenstein,[15] who observed that the Temple Hymns and two hymns to Inanna: The Exaltation of Inanna and another "Hymn to Inanna" (at the time not yet reconstructed) contained references to Enheduanna. Falkenstein suggested that this might be evidence of Enheduanna's authorship, but acknowledged that the hymns are only known from the later Old Babylonian period and that more work would need to be done constructing and analyzing the received texts before any conclusions could be made. In 1989, Westenholz[7] suggested that Inanna and Ebih and two other hymns, to Nanna at Ur, might also have been written by her.

Temple hymns

These hymns have been reconstructed from 37 tablets from Ur and Nippur, most of which date to the Ur III and Old Babylonian periods. Each hymn is dedicated to a particular deity from the Sumerian pantheon and a city with which the deity was associated, and may have helped to create syncreticism between the native Sumerian religion and the Semitic religion of the Akkadian empire.[16] However, some of these poems, such as hymn 9, addressed to the temple of the deified king Sulgi[17] from the later Third Dynasty of Ur, cannot have been written by Enheduanna or anyone in the Akkadian empire, showing that the collection may have gained additional poems over time.

The first translation of the collection into English was by Åke W. Sjöberg,[18] who also argued that the mention of a "subscript" or colophon of two lines near the end of the composition appear to credit her with composition of the preceding text. However, Black[17] shows that in the majority of manuscripts, the line following this colophon, which contains the line count for the 42nd and final hymn, demonstrates that the preceding two lines are part of the 42nd hymn. Black concludes[19] that: "At most... it might be reasonable to accept a claim for (Enheduanna)'s authorship or editorship" for only Hymn 42, the final hymn in the collection.

Hymns dedicated to Inanna

The Exaltation of Inanna

This hymn (incipit nin-me-sar-ra) has been analyzed[20] by Black et al. as consisting of two main parts: The first part (lines 1–65) is a dedication to Inanna, who is not mentioned by name but identified (lines 1–12) by the references to "mes" or "divine power" which are associated with her, which stresses her violent and vengeful nature (lines 13–59). The second part (lines 66-138) is a prayer for forgiveness and revenge narrated by Enheduanna (lines 66–73) speaking in the first person, where she requests intercession from Inanna (lines 74–80) regarding an individual named "Lugal-ane" (lines 81–90). Enheduanna prays for revenge (lines 91–108) and also requests (lines 109–138) that Inanna and Nanna relent from their punishment.

In the short concluding section (lines 139–154) the tone shifts to a time when the prayer has been answered - Enheduanna has been forgiven and restored. Black et al. stress that the historical events surrounding both this poem[21] and the Hymn to Inanna, including the identity of "Lugal-ane",[20] cannot currently be identified. Hallo and Van Dijk published the first translations and book-length discussion of Enheduanna's work in 1968.

Hymn to Inanna

This hymn (incipit in-nin sa-gur-ra) which is only partially preserved in a fragmentary form, is outlined by Black et al.[21] as containing three parts: an introductory section (lines 1-90) emphasizing Inanna's "martial abilities"; a long, middle section (lines 91-218) that serves as a direct address to Inanna, listing her many positive and negative powers, and asserting her superiority over other deities, and a concluding section (219–274) narrated by Enheduanna that exists in a very fragmentary form.

Black et al.[21] surmise that the fragmentary nature of the concluding section makes it unclear whether Enheduanna composed the hymn, the concluding section was a later addition, or that her name was added to the poem later in the Old Babylonian period from "a desire to attribute it to her". They also note that the concluding section also appears to reference "some historical events which cannot be elucidated." [21] This poem also contains a potential reference to the events described in Inanna and Ebih, which has led some assyriologists, including Westenholz[7] to suggest that that poem may have been written by Enheduanna as well.

The first English translation of this work was by Sjöberg[22] in 1975.

Inanna and Ebih

This hymn (incipit in-nin me-hus-a) is characterized[23] by Black et al. as "Inanna in warrior mode." The poem starts with a hymn to Inanna as "lady of battle" (lines 1–24) then shifts to a narration by Innana herself in the first person (lines 25–52), where she describes the revenge she wants to take on the mountains of Ebih for their refusal to bow to her.

Inanna then visits the sky god An and requests his assistance (lines 53–111), but An doubts Inanna's ability to take revenge (lines 112–130). This causes Inanna to fly into a rage and attack Ebih (lines 131–159). Inanna then recounts how she overthrew Ebih (lines 160–181) and the poem ends with a praise of Inanna (lines 182–184).[23] The "rebel lands" of Ebih that are overthrown in the poem have been identified[23] with the Jebel Hamrin mountain range in modern Iraq. Black et al. describe[23] these lands as "home to the nomadic, barbarian tribes who loom large in Sumerian literature as forces of destruction and chaos" that sometimes need to be "brought under divine control".

Hymns dedicated to Nanna

These two hymns, labeled by Westenholz[7] as Hymn of Praise to Ekisnugal and Nanna on [the] Assumption of En-ship (incipit e ugim e-a) and Hymn of Praise of Enheduanna (incipit lost). The second hymn is very fragmentary.

Authorship debate

The question of Enheduanna's authorship of poems has been subject to significant debate.[24] While Hallo[25] and Åke Sjoberg[18] were the first to definitively assert Enheduanna's authorship of the works attributed to her, other Assyriologists including Miguel Civil and Jeremy Black have put forth arguments rejecting or doubting Enheduanna's authorship. Civil[26] has raised the possibility that "Enheduanna" refers not to the name, but instead the station of EN priestess that the daughter of Sargon of Akkad held. This would imply that the poems were not all written by the same "Enheduanna" but that they were each narrated as if spoken by the high priestess. Black stresses that "whether this claim itself dates back to the Agade Period is, of course, a quite separate question" noting that the same phrasing that attributes the authorship of Hymn 42 to Enheduanna is used in the late Babylonian poem Erra and Ishum to attribute that work to the god Erra. For the Inanna and Nanna poems, Black et al. argue[14] that at best, all of the manuscript sources date from at least six centuries after when she would have lived, and they were found in scribal settings, not ritual ones, and that "surviving sources show no traces of Old Sumerian... making it impossible to posit what that putative original might have looked like."

Despite these concerns, Hallo says that there is still little reason to doubt Enheduanna's authorship of these works. Hallo,[27] responding to Miguel Civil, not only still maintains[28] Enheduanna's authorship of all of the works attributed to her, but rejects "excess skepticism" in Assyriology as a whole, and noting that "rather than limit the inferences they draw from it" other scholars should consider that "the abundant textual documentation from Mesopotamia... provides a precious resource for tracing the origins and evolution of countless facets of civilization[27]".

Summarizing the debate, Paul A. Delnero,[29] professor of Assyriology at Johns Hopkins University, remarks that "the attribution is exceptional, and against the practice of anonymous authorship during the period; it almost certainly served to invest these compositions with an even greater authority and importance than they would have had otherwise, rather than to document historical reality".

Influence and legacy

Modern relevance

Enheduanna has received substantial attention in feminism. In a BBC Radio 4 interview, Assyriologist Eleanor Robson credits this to the feminist movement of the 1970s, when, two years after attending a lecture by Cyrus H. Gordon in 1976, American anthropologist Marta Weigle introduced Enheduanna to an audience of feminist scholars as "the first known author in world literature" with her introductory essay "Women as Verbal Artists: Reclaiming the Sisters of Enheduanna".[30] Robson says that after this publication, the "feminist image of Enheduanna... as a wish fulfillment figure" really took off.[31] Rather than as a "pioneer poetess" of feminism,[31] Robson states that the picture of Enheduanna from the surviving works of the 18th century BCE is instead one of her as "her fathers' political and religious instrument".[32] Robson also stresses that we have neither "access to what Enheduanna thought or did"[31] or "evidence that (Enheduanna) was able to write",[33] but that as the high priestess and daughter of Sargon of Akkad, Enheduanna was "probably the most privileged woman of her time"[33] who likely could have had other people write poetry on her behalf. Robson explains this difference between the popular and scholarly conceptions of Enheduanna as "not really what people want to hear, so they possibly choose not to hear it" but she also admits that specialists such as herself may also not communicate clearly enough.

Enheduanna has also been analyzed as an early rhetorical theorist. Roberta Binkley finds evidence in The Exaltation of Inanna of invention and classical modes of persuasion.[34] Hallo, building on the work of Binkley, compares the sequence of the Hymn to Inanna, Inanna and Ebih, and the Exaltation of Inanna to the biblical Book of Amos, and considers these both evidence of "the birth of rhetoric in Mesopotamia."[35]

In popular culture

- Enheduanna is the subject of the 2014 episode "The Immortals" of the science television series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, where she was voiced by Christiane Amanpour.[citation needed]

- In 2015, the International Astronomical Union named a crater on Mercury after Enheduanna as part of a submission contest held by Carnegie Institution of Science to promote the MESSENGER project.[citation needed]

See also

- Kushim (Uruk period) - first known name in any writing

- Puabi - Queen of the First dynasty of Ur (26th century BCE) who may have ruled on her own

- Addagoppe of Harran - high priestess of the moon god Nanna in the Neo-Babylonian Empire

- Diotima of Mantinea - pseudonymous or possibly fictional philosopher who Plato's Socrates attributes the theory of Platonic love in the Symposium

- Sappho, Corinna, Sulpicia - other Ancient women poets whose works survive

- Hypatia - Ancient Greek Neoplatonic philosopher and mathematician of the 4th and 5th century and one of the earliest known women in science

- Anna Komnene - Byzantine author in the 11th century who also helped establish legitimacy for her father's dynasty by writing the Alexiad

Notes

- ^ Ebeling 1938, p. 373.

- ^ Black et al. 2006, pp. 315–316.

- ^ a b Kramer 2010, p. 324.

- ^ Kuhrt 1995, p. 49.

- ^ Liverani 2013, p. 143.

- ^ Frayne 1993, pp. 10–12.

- ^ a b c d Westenholz 1989.

- ^ Westenholz 1989, p. 549.

- ^ Godotti 2016.

- ^ a b Winter 2009, p. 69.

- ^ Winter 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Weadock 1975.

- ^ Black et al. 2006, p. 299.

- ^ a b Black et al. 2006, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Falkenstein 1958.

- ^ Roberts 1972.

- ^ a b Black 2002.

- ^ a b Sjöberg & Bergmann 1969.

- ^ Black 2002, p. 3.

- ^ a b Black et al. 2006, pp. 315.

- ^ a b c d Black et al. 2006, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Sjöberg 1975.

- ^ a b c d Black et al. 2006, p. 334.

- ^ Glassner 2009.

- ^ Hallo & van Dijk 1968.

- ^ Civil 1980.

- ^ a b Hallo 1990, p. 187.

- ^ Hallo 2010, p. 673.

- ^ Delnero 2016.

- ^ Weigle 1978.

- ^ a b c Robson & Minamore 2017, 10:11-10:39.

- ^ Robson & Minamore 2017, 9:35-9:40.

- ^ a b Robson & Minamore 2017, 9:40-9:54.

- ^ Binkley 2004, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Hallo 2010, pp. 127–128.

References

- Binkley, Roberta A. (2004). "The Rhetoric of Origins and the Other: Reading the Ancient Figure of Enheduanna". In Lipson, Carol; Binkley, Roberta A. (eds.). Rhetoric before and beyond the Greeks. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 47–59. ISBN 9780791461006. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- Black, Jeremy (2002). "En‐hedu‐ana not the composer of the Temple Hymns" (PDF). Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires. 1: 2–4. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- Black, Jeremy; Cunningham, Graham; Robson, Eleanor; Zólyomi, Gábor (13 April 2006). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0. Retrieved Dec 9, 2021.

- Civil, Miguel (1980). "Les limites de l'information textuelle". Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

- Ebeling, Erich, ed. (1938). "Ezur und Nachträge". Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-004450-8. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- Delnero, Paul (1 July 2016). "Scholarship and Inquiry in Early Mesopotamia". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History. 2 (2): 109–143. doi:10.1515/janeh-2016-0008. S2CID 133572636. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- Falkenstein, Adam (1958). "Ehedu'anna, Die Tochter Sargons von Akkade". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 52 (2): 129–131. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23295714. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- Frayne, Douglas (1993). Sargonic and Gutian Periods, 2334-2113 BC. University of Toronto Press. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-0-8020-0593-9. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Godotti, Alhena (12 August 2016). "Mesopotamian Women's Cultic Roles in Late 3rd — Early 2nd millennia BCE". In Budin, Stephanie Lynn; Turfa, Jean Macintosh (eds.). Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-21990-3. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- Glassner, Jean-Jacques (2009). "En-hedu-Ana, une femme auteure en pays de Sumer au IIIe millénaire ?". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 10 (1): 219–231. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- Hallo, William W.; van Dijk, J. J. A. (1968). The Exaltation of Inanna. Yale University Press. pp. 1–11.

- Hallo, William W. (1990). "The Limits of Skepticism". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 110 (2): 187–199. doi:10.2307/604525. JSTOR 604525. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- Hallo, William W. (2010). The world's oldest literature : studies in Sumerian belles-lettres. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004173811. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (17 September 2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45232-6. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). The Ancient Near East, C. 3000-330 BC. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-16763-5. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Liverani, Mario (4 December 2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-75084-9. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Roberts, Jimmy Jack Mcbee (1972). The Earliest Semitic Pantheon. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 145–147. ISBN 0-8018-1388-3. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- Robson, Eleanor; Minamore, Bridget (15 October 2017). Lines of Resistance. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- Sjöberg, Åke W.; Bergmann, Eugen (1969). The Collection of the Sumerian Temple Hymns. J. J. Augustin. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- Sjöberg, Åke W. (1 January 1975). "in-nin šà-gur4-ra. A Hymn to the Goddess Inanna by the en-Priestess Enḫeduanna". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie (in German). 65 (2): 161–253. doi:10.1515/zava.1975.65.2.161. ISSN 1613-1150. S2CID 161560381. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- Wagensonner, Klaus (2020). "Between History and Fiction — Enheduana, the First Poet in World Literature". In Wisti-Lassen, Agnete; Wagensonner, Klaus (eds.). Women at the dawn of history. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Babylonian Collection. pp. 39–45. ISBN 978-1-7343420-0-0. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Weadock, Penelope N. (1975). "The Giparu at Ur". Iraq. 37 (2): 101–128. doi:10.2307/4200011. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200011. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- Weigle, Marta (Autumn 1978). "Women as Verbal Artists: Reclaiming the Sisters of Enheduanna". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 3 (3): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3346320. JSTOR 3346320. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- Westenholz, Joan Goodnick (1989). "Enḫeduanna, En-Priestess, Hen of Nanna, Spouse of Nanna". In Behrens, Hermann; Loding, Darlene; Roth, Martha T. (eds.). DUMU-E-DUB-BA-A : Studies in Honor of Åke W. Sjöberg. Philadelphia, PA: The University Museum. pp. 539–556. ISBN 0-93471898-9. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- Wilcke, Claus (1972). "Der aktuelle Bezug der Sammlung der sumerischen Tempelhymnen und ein Fragment eines Klageliedes". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie. 62 (1). doi:10.1515/zava.1972.62.1.35. S2CID 163266334. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- Winter, Irene (27 November 2009). "Women In Public: The Disk Of Enheduanna, The Beginning Of The Office Of En-Priestess, And The Weight Of Visual Evidence". In Winter, Irene (ed.). On Art in the Ancient Near East Volume II: From the Third Millennium BCE. BRILL. pp. 65–84. ISBN 978-90-474-2845-9. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

External links

- English Translations of works attributed to Enheduanna at the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

- Artifacts depicting Enheduanna

- 23rd-century BC births

- 23rd-century BC deaths

- 23rd-century BC writers

- 23rd-century BC women writers

- 23rd-century BC clergy

- 23rd-century BC people

- 1927 archaeological discoveries

- Akkadian Empire

- Akkadian people

- Ancient Asian women writers

- Ancient Near Eastern scribes

- Ancient Mesopotamian women

- Ancient poets

- Ancient priestesses

- Ancient women poets

- Hymnwriters

- Inanna

- Sumerian people

- Ur

- Women hymnwriters

- Women religious writers