The Blue Lagoon (1980 film)

| The Blue Lagoon | |

|---|---|

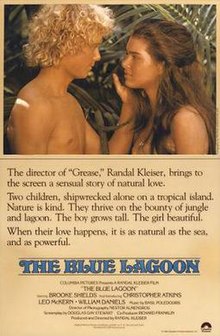

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Randal Kleiser |

| Screenplay by | Douglas Day Stewart |

| Based on | The Blue Lagoon by Henry De Vere Stacpoole |

| Produced by | Randal Kleiser |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Néstor Almendros |

| Edited by | Robert Gordon |

| Music by | Basil Poledouris |

| Color process | Metrocolor |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4.5 million |

| Box office | $58.8 million (North America) |

The Blue Lagoon is a 1980 American romantic and coming-of-age survival drama film directed by Randal Kleiser from a screenplay written by Douglas Day Stewart based on the 1908 novel of the same name by Henry De Vere Stacpoole. The film stars Brooke Shields and Christopher Atkins. The music score was composed by Basil Poledouris and the cinematography was by Néstor Almendros.

The film tells the story of two young children marooned on a tropical island paradise in the South Pacific. But, without either the guidance or the restrictions of society, emotional and physical changes arise as they reach puberty and fall in love.

The Blue Lagoon was theatrically released on June 20, 1980, by Columbia Pictures. The film was panned by the critics, who disparaged its screenplay, execution, and Shields' performance; however, Almendros' cinematography received praise. In spite of the criticism, the film was a commercial success, grossing over $58 million on a $4.5 million budget and becoming the ninth-highest-grossing film of 1980 in North America. The film was nominated for the Saturn Award for Best Fantasy Film, Almendros received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Cinematography, and Atkins was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for New Star of the Year – Actor. Shields won the inaugural Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Actress for her work in the film.

Plot

In the late Victorian period, two cousins, nine-year-old Richard and seven-year-old Emmeline Lestrange, and galley cook Paddy Button, are shipwrecked on a lush tropical island in the South Pacific. Paddy cares for the children and forbids them "by law" from going to the other side of the island, where he had found an altar with bloody remains from human sacrifices. He also warns them against eating the deadly scarlet berries. He dies after a drunken binge and the children rebuild their home on a different part of the island.

At puberty, Emmeline is uncomfortable with her sexual attraction to Richard and declines to share her "funny" thoughts with him. She is frightened by her first menstrual period and refuses to allow Richard to inspect her for what he imagines is a wound.

Eventually, Richard recognizes his own attraction to Emmeline. She ventures to the forbidden side of the island and sees the altar. Associating the blood with Christ's crucifixion, she concludes that the altar is God, and tries to persuade Richard to go to the other side of the island to pray with her. Richard is shocked at the idea of breaking the law, and they argue. When Richard tries to initiate sexual contact she rebuffs him; he hides and masturbates.

When a ship appears for the first time in years, Emmeline does not light the signal fire, and asserts to Richard's angry disbelief that the island is their home now. She says she knows about Richard's masturbation and threatens to tell her Uncle Arthur about it. They fight and Richard kicks Emmeline out of their shelter.

Emmeline steps on a venomous stonefish. Weak from the poison, she pleads with Richard to "take [her] to God". Richard carries her across the island and places her on the altar. Emmeline recovers and they swim naked in the lagoon. Noticing their bodies' reactions, they discover sexual intercourse and become lovers. Neither recognize the fact when Emmeline becomes pregnant, and are stunned to feel the baby move inside her abdomen, assuming her stomach is causing the movements.

Months later, Richard observes indigenous people performing a human sacrifice in front of the statue. He runs in fear to Emmeline, whom he finds in labor. They name their baby boy Paddy.

A ship led by Richard's father, Arthur, approaches the island and sees the family playing on the shore. Content with their lives, Richard and Emmeline walk away instead of signaling for help. Arthur assumes the mud-covered couple are not Richard and Emmeline.

Visiting their original homesite, Richard searches for bananas while Paddy, unnoticed, brings a branch of the scarlet berries into the boat with Emmeline. Paddy tosses an oar out of the boat as it drifts from the shore. Richard swims after them followed closely by a shark. Emmeline throws the other oar at the shark, striking it and giving Richard time to get into the boat. The boat drifts oarless out to sea.

After drifting for days, Richard and Emmeline awake to find Paddy eating the scarlet berries. Hopeless, Richard and Emmeline eat the berries as well, and lie down to await death. Some hours later, Arthur's ship finds them. Arthur asks, "Are they dead?" The officer assures him, "No, sir. They're asleep".

Cast

- Brooke Shields as Emmeline Lestrange

- Elva Josephson as Young Emmeline

- Christopher Atkins as Richard Lestrange

- Glenn Kohan as Young Richard

- Bradley Pryce as Little Paddy Lestrange

- Chad Timmermans as Infant Paddy

- Leo McKern as Paddy Button

- William Daniels as Arthur Lestrange

- Alan Hopgood as Captain

- Gus Mercurio as Officer

Casting

Brooke Shields was cast as Emmeline Lestrange based on her performance in Pretty Baby.

Jodie Foster auditioned for the role of Emmeline Lestrange, but she was turned down. Kelly Preston also auditioned for the role.[1] Diane Lane was offered the role but turned it down.[2] Willie Aames was considered for the role of Richard Lestrange.[1]

Production

The film was a passion project of Randal Kleiser, who had long admired the original novel. He hired Douglas Day Stewart, who had written The Boy in the Plastic Bubble, to write the script and met up with Richard Franklin, the Australian director, who was looking for work in Hollywood. This gave him the idea to use an Australian crew, which Franklin helped supervise.[3]

The film was shot at Nanuya Levu, a privately owned island in Fiji.[4] The flora and fauna featured in the film includes an array of animals from multiple continents, including a species of iguana hitherto unknown to biologists. Herpetologist John Gibbons traveled to the island where the iguana was filmed after watching the film and described the Fiji crested iguana (Brachylophus vitiensis) in 1981.[5]

Shields was 14 years of age when she appeared in the film.[6] All of her nude scenes were performed by the film's 32-year-old stunt coordinator, Kathy Troutt.[7] Shields did many of her topless scenes with her hair glued to her breasts.[8][9] Atkins was 18 when the movie was filmed, and he performed his own nude scenes (which included brief frontal nudity).[10][11][12]

Underwater moving picture photography was performed by Ron Taylor and Valerie Taylor.[13]

Reception

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes the film holds an approval rating of 8% based on 25 reviews, with an average rating of 3.3/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "A piece of lovely dreck, The Blue Lagoon is a naughty fantasy that's also too chaste to be truly entertaining."[14] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 31 out of 100, based on 14 critics, indicating "generally unfavorable reviews".[15]

Among the more common criticisms were the ludicrously idyllic portrayal of how children would develop outside of civilized society,[7][16][17] the unfulfilled buildup of the island's natives as a climactic threat[7][16] and the way the film, while teasing a prurient appeal, conspicuously obscures all sexual activities.[16][17] Roger Ebert gave the film 1½ stars out of 4, claiming that it "could conceivably have been made interesting, if any serious attempt had been made to explore what might really happen if two 7-year-old kids were shipwrecked on an island. But this isn't a realistic movie. It's a wildly idealized romance, in which the kids live in a hut that looks like a Club Med honeymoon cottage, while restless natives commit human sacrifice on the other side of the island." He also deemed the ending a blatant cop-out.[16] He and Gene Siskel selected the film as one of their "dogs of the year" in a 1980 episode of Sneak Previews.[18] Time Out commented that the film "was hyped as being about 'natural love'; but apart from 'doing it in the open air', there is nothing natural about two kids (unfettered by the bonds of society from their early years) subscribing to marriage and traditional role-playing."[17] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post similarly called the film "a picturesque rhapsody to Learning Skills, Playing House, Going Swimming, Enjoying the Scenery and Starting to Feel Sexy in tropical seclusion." He particularly ridiculed the lead characters' persistent inability to make obvious inferences.[7] One of the few positive reviews came from Variety which claimed it "a beautifully mounted production."

In a retrospective review for RogerEbert.com, critic Abbey Bender wrote, "When it comes to the depiction of burgeoning sexuality, 'The Blue Lagoon' wants to have it both ways ... with puberty making itself known through rather obvious dialogue. Sexual discovery is here the natural outcome of the storybook situation. So yes, the soft-focus montages of teen flesh are gratuitous but the film presents it all as innocent—these kids don’t even know what sex is! They don’t even know how a baby is made! They learn it the hard way, obviously. By couching sexuality in primitive purity, 'The Blue Lagoon' gets away with perversion that would likely be even more controversial today."[6]

Box office

The film was the twelfth-biggest box office hit of 1980 in North America according to The Numbers,[19] grossing US$58,853,106 in the United States and Canada[20] on a $4.5 million budget.[21][22][23]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[24] | Best Cinematography | Néstor Almendros | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards[25] | New Star of the Year – Actor | Christopher Atkins | Nominated |

| Golden Raspberry Awards | Worst Actress | Brooke Shields | Won |

| Jupiter Awards | Best International Actress | Won | |

| Saturn Awards | Best Fantasy Film | Nominated | |

| Stinkers Bad Movie Awards | Worst Actor | Christopher Atkins | Nominated |

| Worst Actress | Brooke Shields | Won | |

| Most Intrusive Musical Score | Basil Poledouris | Won | |

| Worst On-Screen Couple | Christopher Atkins and Brooke Shields | Nominated | |

| Young Artist Awards | Best Major Motion Picture – Family Entertainment | Nominated | |

| Best Young Actor in a Major Motion Picture | Christopher Atkins | Nominated | |

| Best Young Actress in a Major Motion Picture | Brooke Shields | Nominated | |

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated[26]

Versions and adaptations

The Blue Lagoon was based on Henry De Vere Stacpoole's novel of the same name, which first appeared in 1908. The first film adaptation of the book was the British silent 1923 film of that name, which is now lost. There was another British adaptation in 1949.[27]

The sequel Return to the Blue Lagoon (1991) loosely picked up where The Blue Lagoon left off, except that Richard and Emmeline are found dead in the boat. Their son is rescued.[28]

On December 9, 2011, the cable TV network Lifetime greenlit the television film Blue Lagoon: The Awakening.[29]

The 1982 Indian film Ina, directed by I. V. Sasi, is inspired by The Blue Lagoon. The story is set in Indian state of Kerala and explores teen lust, child marriage and the consequences. 1984 Indian film Teri Baahon Mein and 1991 Hindi film Jaan Ki Kasam are also inspired by it.[30]

Home media

The Special Edition DVD, with both widescreen and fullscreen versions, was released on October 5, 1999. Its special features include the theatrical trailer, the original featurette, a personal photo album by Brooke Shields, audio commentary by Randal Kleiser and Christopher Atkins, and another commentary by Randal Kleiser, Douglas Day Stewart and Brooke Shields.[31] The film was re-released in 2005 as part of a two-pack with its sequel, Return to the Blue Lagoon.[32]

A limited edition Blu-ray Disc of the film was released on December 11, 2012, by Twilight Time. Special features on the Blu-ray include an isolated score track, original trailer, three original teasers, a behind the scenes featurette called An Adventure in Filmmaking: The Making of The Blue Lagoon, as well as audio commentary by Randal Kleiser, Douglas Day Stewart and Brooke Shields and a second commentary by Randal Kleiser and Christopher Atkins.[33][34]

The 1980 movie was made available for streaming through services such as Amazon Video and Vudu.[35][36]

See also

- The Blue Lagoon (1923 version)

- The Blue Lagoon (1949 version)

- Return to the Blue Lagoon

- Blue Lagoon: The Awakening, a Lifetime television movie

- Paradise

References

- ^ a b Kelly Preston Was Approached For ‘Blue Lagoon’ | WWHL. Watch What Happens Live with Andy Cohen. June 12, 2018. Archived from the original on August 28, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Mell, Eila (January 24, 2015). Casting Might-Have-Beens: A Film by Film Directory of Actors Considered for Roles Given to Others. ISBN 9781476609768.

- ^ Scott Murray, "The Blue Lagoon: Interview with Randal Kleiser", Cinema Papers, June–July 1980 [166-169, 212]

- ^ McMurran, Kristin (August 11, 1980). "Too Much, Too Young?". People. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ Robert George Sprackland (1992). Giant lizards. Neptune, New Jersey: T.F.H. Publications. ISBN 0-86622-634-6.

- ^ a b Bender, Abbey (March 4, 2019). "Sexualized Innocence: Revisiting The Blue Lagoon". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on April 5, 2020. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Arnord, Gary (July 11, 1980). "Depth Defying". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ The Blue Lagoon (DVD Special Edition). Released October 5, 1999.

- ^ "SCREEN ARCHIVES ENTERTAINMENT". Screenarchives.com. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ McMurrin, Kristin (August 11, 1980). "Too Much, Too Young?". People. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "Christopher Atkins: Poster Child for Gay Rights Movement?". Advocate.com. January 9, 2009. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "Chris Atkins". HollywoodShow.com. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ Valerie and Ron Taylor join the action in 'THE BLUE LAGOON', The Australian Women's Weekly, November 19, 1980, pages 64 and 65, Retrieved February 17, 2013

- ^ "The Blue Lagoon (1980)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Blue Lagoon Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Ebert, Roger. "The Blue Lagoon Movie Review & Film Summary (1980) – Roger Ebert". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c FF. "The Blue Lagoon (1980)". Time Out. Archived from the original on October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Sneak Previews: Worst of 1980". Siskelandebert.org. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Numbers - Top-Grossing Movies of 1980". Archived from the original on February 4, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ "1980 Yearly Box Office Results". Boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Blue Lagoon (1980) - Financial Information". Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". Archived from the original on June 10, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "The Blue Lagoon". Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "The 53rd Academy Awards (1981) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ "The Blue Lagoon – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Afi.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Lifetime is remaking "The Blue Lagoon"". Reuters. December 10, 2011. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Cedrone, Lou. "'Return to the Blue Lagoon' is for those who liked original". baltimoresun.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (December 9, 2011). "Lifetime Greenlights 'Blue Lagoon' Remake". Deadline.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ Arunachalam, Param. BollySwar: 1991 - 2000. Mavrix Infotech Private Limited. ISBN 978-81-938482-1-0.

- ^ "The Blue Lagoon". Amazon.com. October 5, 1999. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Blue Lagoon / Return to the Blue Lagoon". Amazon.com. February 1, 2005. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "The Blue Lagoon Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ The Blue Lagoon Blu-ray, Twilight Time, 2012

- ^ "Amazon.com: The Blue Lagoon: Christopher Atkins, Brooke Shields, William Daniels, Leo McKern: Amazon Digital Services LLC". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "Vudu – The Blue Lagoon". Vudu.com. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

External links

- 1980 films

- 1980 drama films

- 1980s adventure drama films

- 1980s coming-of-age drama films

- 1980s romantic drama films

- 1980s teen drama films

- 1980s teen romance films

- American adventure drama films

- American coming-of-age films

- American remakes of British films

- American romantic drama films

- American survival films

- American teen drama films

- American teen romance films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Coming-of-age romance films

- Films about castaways

- Films about children

- Films about cousins

- Films about survivors of seafaring accidents or incidents

- Films about virginity

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on romance novels

- Films based on works by Henry De Vere Stacpoole

- Films directed by Randal Kleiser

- Films scored by Basil Poledouris

- Films set in Oceania

- Films set in the 19th century

- Films set in the 1880s

- Films set in 1889

- Films set in the 1890s

- Films set in 1895

- Films set in 1897

- Films set in the Victorian era

- Films set on beaches

- Films set on islands

- Films set on uninhabited islands

- Films shot in Fiji

- Films with screenplays by Douglas Day Stewart

- Golden Raspberry Award winning films

- Incest in film

- Juvenile sexuality in films

- Teen adventure films

- Teenage pregnancy in film

- Films about puberty

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s American films