Philosophical pessimism

Philosophical pessimism is a family of philosophical views that assign a negative value to life or existence. Philosophical pessimists commonly argue that the world contains an empirical prevalence of pains over pleasures, that existence is ontologically or metaphysically adverse to living beings, and that life is fundamentally meaningless or without purpose.[1] Their responses to this condition, however, are widely varied and can be life-affirming.[2][3]

Philosophical pessimism is not a single coherent movement, but rather a loosely associated group of thinkers with similar ideas and a resemblance to each other.[4]: 7 In Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860-1900, Frederick C. Beiser describes philosophical pessimism as "the thesis that life is not worth living, that nothingness is better than being, or that it is worse to be than not be".[5][6] Although adherents of philosophical pessimism rarely advocate for suicide as a solution to the human predicament, many of its proponents do favour the adoption of antinatalism, that is, non-procreation.[7]

Development of pessimist thought

In religion

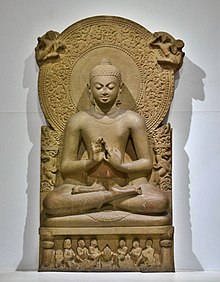

Buddhism

Historically, philosophical pessimism seems to have first presented itself in the East, under the partly religious aspect of Buddhism.[8][9] In the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, Gautama Buddha establishes the first noble truth of duḥkha, or suffering, as the fundamental mark of existence:[10]

Now this, bhikkhus, is the noble truth of suffering: birth is suffering, aging is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering; union with what is displeasing is suffering; separation from what is pleasing is suffering; not to get what one wants is suffering; in brief, the five aggregates subject to clinging are suffering.

This would have exerted a certain influence on Greco-Roman philosophy from the Ptolemaic period onwards, in particular on the pessimistic doctrine of Hegesias of Cyrene.[11][12] This thesis is notably advanced by Jean-Marie Guyau who, in the middle of the controversy about German pessimism (1870–1890), detects in Hegesias's philosophy the pessimistic theme of Buddhism, which he sees as a "palliative of life"; he summarizes it as follows:[13]

Most often, hope brings with it disappointment, enjoyment produces satiety and disgust; in life, the sum of sorrows is greater than that of pleasures; to seek happiness, or only pleasure, is therefore vain and contradictory, since in reality, one will always find a surplus of sorrows; what one must tend to is only to avoid sorrow; now, in order to feel less sorrow, there is only one way: to make oneself indifferent to the pleasures themselves and to what produces them, to blunt sensitivity, to annihilate desire. Indifference, renunciation, here is thus the only palliative of life.

Judaism and Christianity

The Ecclesiastes is a piece of wisdom literature from the Christian Old Testament.[14] In chapter 1, the author expresses his view towards the vanity (or meaninglessness) of human endeavors in life:[15]

The words of the Teacher, son of David, king in Jerusalem: "Meaningless! Meaningless!" says the Teacher. "Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless." What do people gain from all their labors at which they toil under the sun? Generations come and generations go, but the earth remains forever. The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises. The wind blows to the south and turns to the north; round and round it goes, ever returning on its course. All streams flow into the sea, yet the sea is never full. To the place the streams come from, there they return again. All things are wearisome, more than one can say. The eye never has enough of seeing, nor the ear its fill of hearing. What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.

Death is a major component of the author's pessimism.[16] Though he views wisdom as more valuable than folly, death essentially vitiates its superiority, and because of this the author comes to abhor life:[17]

I saw that wisdom is better than folly, just as light is better than darkness. The wise have eyes in their heads, while the fool walks in the darkness; but I came to realize that the same fate overtakes them both. Then I said to myself, “The fate of the fool will overtake me also. What then do I gain by being wise?” I said to myself, “This too is meaningless.” For the wise, like the fool, will not be long remembered; the days have already come when both have been forgotten. Like the fool, the wise too must die! So I hated life, because the work that is done under the sun was grievous to me. All of it is meaningless, a chasing after the wind.

In chapter 4, the author also expresses antinatalistic thoughts, articulating that, better than those who are already dead, is he who was not yet been born:[18]

Again I looked and saw all the oppression that was taking place under the sun: I saw the tears of the oppressed—and they have no comforter; power was on the side of their oppressors—and they have no comforter. And I declared that the dead, who had already died, are happier than the living, who are still alive. But better than both is the one who has never been born, who has not seen the evil that is done under the sun.

Some parallels have been made between the Book of Ecclesiastes and an ancient Mesopotamian literary composition named the Dialogue of Pessimism,[19] composed around 1500 BCE in ancient Mesopotamia. Taking the form of a dialogue between a master and slave, the master in the exchange cannot decide on any course of action, giving orders to his slave before immediately cancelling them and driving him to the point of desperation, which has been interpreted as an expression of the futility of human actions.[20][21]

In the Bible, Jesus sometimes showed doubts about the value of the world, for example, in the Gospel of John: "If you belonged to the world, the world would love you as its own. Because you do not belong to the world, but I have chosen you out of the world—therefore the world hates you."[22]

Gnosticism

Gnosticism is a complex religious movement steeped in Greco-Latin philosophy, most often claiming to be "true" Christianity, although it is considered heretical by the Catholic Church. It is characterized by a philosophy of salvation based on "gnosis", in other words on the knowledge of the divine, and by its denigration of the earthly world, created by an evil power. In general, the gnostic considers his body negatively: it is the "prison", the "tomb", or the "corpse" where his authentic self has been locked up.[23] It is a foreign thing that must be endured, an "unwanted companion" or an "intruder" that drags the spirit down, plunging it into the degrading oblivion of its origin.[23] The flesh is interpreted in this sense as a state of humiliation and suffering engendered by a demonic force, perverted or weakened, lurking in matter. This state condemns all men to live in a kind of hell which is none other than the sensible world.[23] The pessimistic vision of the Gnostics extends to all the cosmos, conceived as a failed work, even fatal or criminal. Man is "thrown" into it, then locked up without hope.[23]

In Gnostic thought, the problem of evil is a nagging question which leads to the adoption of a dualistic perspective.[23] Indeed, the gnostic is led either to oppose God and the spirit to matter or to an evil principle, or else to distinguish from the transcendent God, unknown or foreign to the world and absolutely good, an inferior or enemy god, creator of the world and of bodies. In this last case, the divine, rejected entirely out of the sensible, only remains in the "luminous" part of the human soul,[23] extinguished however in the great majority of men. In addition to affirming the intrinsically evil character of the world, the Gnostic conceives it as hermetically sealed, surrounded by "outer darkness", by a "great sea" or by an "iron wall" identified with the firmament.[23] Not only is it fortified against God, but God himself has been forced to fortify himself against the world's reach. Inexorable barriers thus oppose the escape of the soul from the earthly realm.[23]

Inhabited by the feeling of being a stranger to the world, where he has been made to fall, the gnostic discovers that he is in essence a native of a beyond, although his body and his lower passions belong to this world. He then understands that he is of the race (genos) of the chosen ones, superior and "hypercosmic" beings.[23] If he desperately yearns for an afterlife, it is because he experiences within himself a throbbing nostalgia for the original homeland from which he has fallen. This longing affects the upper part of his soul, which is a divine principle in exile here on earth, and which can only be saved by the recognition of its original origin—gnosis proper.[23] Those whose higher part of the soul has remained extinct, or who are devoid of it, that is to say, all the individuals whom the Gnostics call hylics (the majority of human beings and all animals), are condemned to destruction or to wander in this world, undergoing the terrifying cycle of reincarnations.[23]

Ancient Greece

Hegesias of Cyrene

Hegesias of Cyrene was a Greek philosopher born in Cyrene, Libya, around the year 290 BC.[24] He came from the dual Socratic and hedonistic tradition of the Cyrenaic school,[25] but is clearly distinguished from it by the radical philosophical pessimism attributed to him. All his writings have been lost and we only know of his philosophy through what Diogenes Laërtius says about him, who considered him as "the advocate of suicide".[26] Laërtius first lends to Hegesias the explicit affirmation of the impossibility of happiness: like later philosophical pessimists, Hegesias argued that lasting happiness is impossible to achieve and that all we can do is to try to avoid pain as much as possible:[27]: 92

Complete happiness cannot possibly exist; for that the body is full of many sensations, and that the mind sympathizes with the body, and is troubled when that is troubled, and also that fortune prevents many things which we cherished in anticipation; so that for all these reasons, perfect happiness eludes our grasp.

Hegesias held that all external objects, events, and actions are indifferent to the wise man, even death: "for the foolish person it is expedient to live, but to the wise person it is a matter of indifference".[28] According to Cicero, Hegesias wrote a book called Death by Starvation, which supposedly persuaded many people that death was more desirable than life (consequently earning him the nickname Peisithanatos, that is, Death-persuader).[27]: 89 Because of this, Ptolemy II Philadelphus banned Hegesias from teaching in Alexandria.[29]

Middle Ages

Al-Ma'arri and Omar Kayyam are two medieval writers noted for their expression of a philosophically pessimistic worldview in their poetry.[30] Al-Ma'arri held an antinatalist view, in line with his pessimism, arguing that children should not be born to spare them of the pains and suffering of life.[31]

17th century

Baltasar Gracián

Baltasar Gracián's novel El Criticón ("The Critic") is considered to be an extended allegory of the human search for happiness which turns out to be fruitless on Earth; the novel paints a bleak and desolate picture of the human condition.[32]

His book of aphorisms, The Pocket Oracle and Art of Prudence ("Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia") deals with the cultural ideal of desengaño, which is commonly translated as disenchantment or disillusionment. However, Gracian is said to have asserted that the journey of life is one where a person loses the misconceptions of the world, but not the illusions.[33] Jennifer A. Herdt argues that Gracian held that "what the world values is deceptive simply because it appears solid and lasting but is in fact impermanent and transitory. Having realized this, we turn from the pursuit of things that pass away and strive to grasp those that do not."[33]

Arthur Schopenhauer engaged extensively with Gracián's works and considered El Criticón "Absolutely unique ... a book made for constant use ... a companion for life ... [for] those who wish to prosper in the great world".[34] Schopenhauer's pessimistic outlook was influenced by Gracián, and he translated The Pocket Oracle and Art of Prudence into German. He praised Gracián for his aphoristic writing style (conceptismo) and often quoted him in his works.[35]

Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal approached pessimism from a Christian perspective. He is noted for publishing the Pensées, a pessimistic series of aphorisms with the intention to highlight the misery of the human condition and turn people towards the salvation of the Catholic Church and God.[36]

A mathematician and physicist of the first order, Pascal turned more and more to religion and faith since a mystical experience he had at the age of thirty.[37]: 193 Embracing the Jansenist current of Christianity, he considered that man is condemned, as a result of the original sin, to perpetual misery. This misery we seek by all means to evade it: "Men, not having been able to cure death, misery, and ignorance, advised themselves, to make themselves happy, not to think about it".[38] In order to forget our condition, not only do we limit our thoughts to the consideration of futile things, but we multiply our gesticulations and vain activities.[37]: 199 The will which pushes us thus towards the inessential belongs to what Pascal calls "entertainment ".[37]: 199 Any life that does not involve the thought of its finitude is a life of entertainment that leads away from God. Entertainment takes extremely varied forms and a very large place in our ordinary existence.[37]: 199 Now, Pascal affirms, if the only thing that consoles us from our miseries is indeed entertainment, it is also "the greatest of our miseries".[39]

For Pascal, action is necessarily subject to entertainment and it is therefore in thought, and not in action, that all our dignity resides.[37]: 200 But the thought in question is not that of the geometer, the physicist or the philosopher who, more often than not, feeds on pride and leads away from God.[37]: 201 It is the introspective discovery and knowledge of our finitude, which alone can raise us above other creatures and bring us closer to God.[37]: 200 "Man is only a reed, the weakest of nature, but he is a thinking reed" declares in this sense Pascal in a famous maxim.[40] Thought is an essence of man to which he owes his greatness, but only insofar as it reveals to him his finitude.[37]: 201 The Christian idea of man's irretrievability is therefore not only a truth, but a belief that must be adopted, because it alone gives human existence a certain dignity. Pascal promotes in this perspective a reflexive form of pessimism, linking greatness and misery, where the disconsideration of oneself and the recognition of our impotence raise us above ourselves, making us renounce at the same time the vain search for happiness.[37]: 202–203

18th century

Voltaire

In response to the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, Voltaire penned the pessimistic "Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne" ("Poem on the Lisbon Disaster"), which critiqued Pope's optimistic axiom in the poem "An Essay on Man" that "all is well"; Voltaire had initially praised Pope's poem, but later in life became critical of Pope's expressed worldview.[41] "Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne" is especially pessimistic about the state of mankind and the nature of God.[42] In response to the poem, Jean-Jacques Rousseau sent Voltaire a letter asserting that "all human ills are the result of human faults".[42]

Voltaire was the first European to be labeled as a pessimist by his critics, in response to the publication and international success of his 1759 satirical novel Candide;[4]: 9 a treatise against Leibniz's theistic optimism, refuting his affirmation that "we live in the best of all possible worlds."[43] Though himself a Deist, Voltaire argued against the existence of a compassionate personal God through his interpretation of the problem of evil.[44]

19th century

Giacomo Leopardi

Though a lesser-known figure outside Italy, Giacomo Leopardi was highly influential in the 19th century, especially on Schopenhauer and Nietzsche.[4]: 50 In Leopardi's darkly comic essays, aphorisms, fables and parables, life is often described as a sort of divine joke or mistake.[4]: 52 For Leopardi, humans have an unlimited desire for pleasure, which cannot however be satisfied by any specific joy. In this perspective, the existential problem for human beings emerges in the actual desire for particular existent pleasures, for these are all finite and thus cannot satisfy the desire for the infinite:[47]

The sense of the nothingness of all things, the inadequacy of each and every pleasure to fill our spirit, and our tendency toward an infinite that we do not understand comes perhaps from a very simple cause, one that is more material than spiritual. The human soul (and likewise all living beings) always essentially desires, and focuses solely (though in many different forms), on pleasure, or happiness, which, if you think about it carefully, is the same thing. This desire and this tendency has no limits, because it is inborn or born along with existence itself, and so cannot reach its end in this or that pleasure, which cannot be infinite but will end only when life ends. And it has no limits (1) either in duration (2) or in extent. Hence there can be no pleasure to equal (1) either its duration, because no pleasure is eternal, (2) or its extent, because no pleasure is beyond measure, but the nature of things requires that everything exist within limits and that everything have boundaries, and be circumscribed.

Going against the Socratic view present ever since Plato's dialogues, which associates wisdom or knowledge with happiness,[48] Leopardi claims that philosophy, by putting an end to false opinions and ignorance, reveals to humans truths that are opposed to their happiness: "Those who say and preach that the perfection of man consists in the knowledge of truth and that all his ills come from false opinions and from ignorance are quite wrong. And so are those who say that the human race will finally be happy when all or the great majority of men know the truth and organize and govern their lives according to its norms."[49]: 411–413 For Leopardi, the ultimate conclusion that philosophizing leads us to is that, paradoxically, we must not philosophize. Such conclusion, however can only be learned at one's own expense, and even once it has been learned, it can't be put in operation because "it is not in the power of men to forget the truths they know and because one can more easily lay aside any other habit than that of philosophizing. In short, philosophy starts out by hoping and promising to cure our ills and ends up by desiring in vain to find a remedy for itself."[49]: 413

Leopardi regarded nature itself as antagonistic to the happiness of man and all other creatures.[50] In his "Dialogue Between Nature and an Icelander", the titular Icelander relates how, in his attempt to escape from suffering, he found himself attacked by severe weather, natural disasters, other animals, diseases, and aging. At the end of the dialogue, the Icelander asks Nature: "For whose pleasure and service is this wretched life of the world maintained, by the suffering and death of all the beings which compose it?", to which Nature does not directly give a response; instead, two famished lions suddenly appear and devour the Icelander, thus gainining the strength to live another day.[51]

Leopardi's response to these conditions was to face up to these realities and try to live a vibrant and great life, to be risky and take up uncertain tasks. He asserted that this uncertainty makes life valuable and exciting, but does not free humans from suffering; it is rather an abandonment of the futile pursuit of happiness. He used the example of Christopher Columbus who went on a dangerous and uncertain voyage and because of this grew to appreciate life more fully.[52] Leopardi also saw the capacity of humans to laugh at their condition as a laudable quality that can help them deal with their predicament: "He who has the courage to laugh is master of the world, much like him who is prepared to die."[53]

German pessimism

Although the first manifestations of philosophical pessimism date back to antiquity,[54] never before did it take such a systematic turn and been so reflected upon as in Germany during the second half of the nineteenth century.[55]: 4 For almost fifty years, the issue of pessimism was discussed in the context of Weltschmerz.[55]: 4 The question of pessimism dominated German philosophical thought, and the "pessimism controversy" was its major point of dispute.[55]: 8 The discussion that took place in Germany around this movement largely agreed on what constituted its central thesis, in other words, the thesis of the negative value of existence.[5]

Arthur Schopenhauer

The first presentation of philosophical pessimism in a systematic manner, with an entire structure of metaphysics underlying it, was introduced by German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer in the 19th century.[56][57][58][59] Schopenhauer's pessimism came from his analysis of life being the product of an insatiable and incessant cosmic Will. He considered the Will to be the ultimate metaphysical animating noumenon, describing it as an aimless, restless and unquenchable striving, encompassing both the inorganic and organic realm, and whose most intuitive and direct apprehension can be attained by man through an observation of his own body and desires:[60]

In nature-without-knowledge her inner being [is] a constant striving without aim and without rest, and this stands out much more distinctly when we consider the animal or man. Willing and striving are its whole essence, and can be fully compared to an unquenchable thirst. The basis of all willing, however, is need, lack, and hence pain, and by its very nature and origin it is therefore destined to pain. If, on the other hand, it lacks objects of willing, because it is at once deprived of them again by too easy a satisfaction, a fearful emptiness and boredom come over it; in other words, its being and its existence itself become an intolerable burden for it. Hence its life swings like a pendulum to and fro between pain and boredom, and these two are in fact its ultimate constituents.

Schopenhauer saw human reason as weak and insignificant compared to Will; in one metaphor, he compared the human intellect to a sighted lame man, who rides on the shoulders of a strong but blind man (the Will).[61] He noted that, once one's desires are satiated, the feeling of satisfaction does not last for long, being merely the starting-point of new desires, and that, as a result, humans spend most of their lives in a state of endless striving; in this sense, they are, deep down, nothing but Will.[62] Even the moments of satisfaction, when attained and not immediately giving way to new wants and longings, only lead one to an abandonment to boredom,[60] which for Schopenhauer is a direct proof that existence has no real value in itself:[63]

For what is boredom but the feeling of the emptiness of life? If life—the craving for which is the very essence of our being—were possessed of any positive intrinsic value, there would be no such thing as boredom at all: mere existence would satisfy us in itself, and we should want for nothing.

Moreover, Schopenhauer argued that the business of biological life is a war of all against all, filled with constant strife and struggle, not merely boredom and unsatisfied desires. In such struggle, each different phenomenon of the will-to-live contests with one another to maintain its own phenomenon:[64]

This universal conflict is to be seen most clearly in the animal kingdom. Animals have the vegetable kingdom for their nourishment, and within the animal kingdom again every animal is the prey and food of some other. This means that the matter in which an animal's Idea manifests itself must stand aside for the manifestation of another Idea, since every animal can maintain its own existence only by the incessant elimination of another's. Thus the will-to-live generally feasts on itself, and is in different forms its own nourishment, till finally the human race, because it subdues all the others, regards nature as manufactured for its own use. Yet ... this same human race reveals in itself with terrible clearness that conflict, that variance of the will with itself, and we get homo homini lupus.

He also asserted that pleasure and pain were asymmetrical: pleasure has a negative nature, while pain is positive. By this Schopenhauer meant that pleasure does not come to us originally and of itself, that is, pleasure is only able to exist as a removal of a pre-existing pain or want, while pain directly and immediately proclaims itself to our perception:[65][66]

All satisfaction, or what is commonly called happiness, is really and essentially always negative only, and never positive. It is not a gratification which comes to us originally and of itself, but it must always be the satisfaction of a wish. For desire, that is to say, want, is the precedent condition of every pleasure; but with the satisfaction, the desire and therefore the pleasure cease; and so the satisfaction or gratification can never be more than deliverance from a pain, from a want. ... What is immediately given to us is always only the want, i.e., the pain. The satisfaction and pleasure can be known only indirectly by remembering the preceding suffering and privation that ceased on their entry.[67]

Regarding old age and death, to which every life necessarily hurries, Schopenhauer described them as a sentence of condemnation from nature itself on each particular phenomenon of the will-to-live, indicating that the whole striving of each phenomenon is bound to frustrate itself and is essentially empty and vain, for if we were something valuable in itself, or unconditioned and absolute, we would not have non-existence as our goal:[66]

What a difference there is between our beginning and our end! The former in the frenzy of desire and the ecstasy of sensual pleasure; the latter in the destruction of all the organs and the musty odour of corpses. The path from birth to death is always downhill as regards well-being and the enjoyment of life; blissfully dreaming childhood, light-hearted youth, toilsome manhood, frail and often pitiable old age, the torture of the last illness, and finally the agony of death. Does it not look exactly as if existence were a false step whose consequences gradually become more and more obvious?[68]

Schopenhauer saw in artistic contemplation a temporary escape from the act of willing. He believed that through "losing yourself" in art one could sublimate the Will. However, he believed that only resignation from the pointless striving of the Will to live through a form of asceticism, which he interpreted as a "mortification of the will" or the "denial of the will-to-live" (as those practiced by eastern monastics and by "saintly persons") could free oneself from the Will altogether.[69]

Schopenhauer never used the term pessimism to describe his philosophy but he also did not object when others called it that.[70] Other terms used to describe his thought are voluntarism and irrationalism, which he also never used.[71][72]

Post-Schopenhauerian pessimism

During the final years of Schopenhauer's life and subsequent years after his death, post-Schopenhauerian pessimism became a popular trend in 19th-century Germany.[73] Nevertheless, it was viewed with disdain by the other popular philosophies at the time, such as Hegelianism, materialism, neo-Kantianism and the emerging positivism. In an age of upcoming revolutions and exciting discoveries in science, the resigned and anti-progressive nature of the typical pessimist was seen as a detriment to social development. To respond to this growing criticism, a group of philosophers greatly influenced by Schopenhauer (indeed, some even being his personal acquaintances) developed their own brand of pessimism, each in their own unique way. Thinkers such as Julius Bahnsen, Eduard von Hartmann, Philipp Mainländer and others cultivated the ever-increasing threat of pessimism by converting Schopenhauer's transcendental idealism into what Frederick C. Beiser calls transcendental realism.[note 1][55]: p. 213 n. 30 The transcendental idealist thesis is that humans know only the appearances of things (not things-in-themselves); the transcendental realist thesis is that "the knowledge we have of how things appear to us in experience gives us knowledge of things-in-themselves."[55]: 147–148

By espousing transcendental realism, Schopenhauer's own dark observations about the nature of the world would become completely knowable and objective, and in this way, they would attain certainty. The certainty of pessimism being, that non-existence is preferable to existence. That, along with the metaphysical reality of the Will, were the premises which the post-Schopenhauerian thinkers inherited from Schopenhauer's teachings. From this common starting point, each philosopher developed their own negative view of being in their respective philosophies.[55]: 147–148

Some pessimists would assuage the critics by accepting the validity of their criticisms and embracing historicism, as was the case with Schopenhauer's literary executor Julius Frauenstädt and with Eduard von Hartmann (who gave transcendental realism a unique twist).[55]: 147–148 Agnes Taubert, the wife of Von Hartmann, in her work Pessimism and Its Opponents defined pessimism as "a matter of measuring the eudaimonological value of life in order to determine whether existence is preferable to non-existence or not"; like her husband, Taubert argued that the answer to this problem is "empirically ascertainable".[74] Olga Plümacher was critical of Schopenhauer's pessimism for "not achieving as good a pessimism as he might have done", and was, as a result, inferior to Von Hartmann's thought on the subject, which allowed for the social progress.[75] Julius Bahnsen would reshape the understanding of pessimism overall,[55]: 231 while Philipp Mainländer set out to reinterpret and elucidate the nature of the will, by presenting it as a self-mortifying will-to-death.[55]: 202

Julius Bahnsen

The pessimistic outlook of the German philosopher Julius Bahnsen is often described as the most extreme form of philosophical pessimism, perhaps even more so than Mainländer's since it excludes any possibility of redemption or salvation, with Bahnsen being skeptical that art, asceticism or even culture can remove us from this world of suffering, or that they provide escape from the self-torment of the will.[55]: 231 According to Bahnsen, the heart of reality lies in the inner conflict of the will, divided within itself and "willing what it does not will and not willing what it wills".[55]: 229 Rather than just a variation of Schopenhauer’s philosophy, but similar to Hartmann’s philosophy, Bahnsen’s worldview is a synthesis of Schopenhauer with Hegel. But while Hartmann attempts to moderate Schopenhauer's pessimisim with Hegel's optimistic belief in historical progress, Bahnsen's philosophy excludes any evolution or progress in history due to seeing it as cyclical and with contradiction being a constant.[55]: 231 When taking Hegel's dialectic as a influence (but not his historicism), Bahnsen takes only the negative moment of his dialectic, or in other words, its emphasis on contradiction. Thus, the main theme of Bahnsen's philosophy became his own idea of the Realdialektik, according to which there is no synthesis between two oposing forces, with the opposition resulting only in negation and the consequent destruction of contradicting aspects. For Bahnsen, no rationality was to be found in being and thus, there was no teleological power that led to progress at the end of every conflict.[55]: 231

Philipp Mainländer

Philipp Mainländer was a poet and philosopher mainly known for his magnum opus "The Philosophy of Redemption" (Die Philosophie der Erlösung), a work marked by a profound pessimism that he had published just before his suicide in 1876. For Theodor Lessing, it is "perhaps the most radical system of pessimism known to philosophical literature",[76][page needed] although it is part of Schopenhauer's philosophical heritage. Mainländer articulates in it the concept of the "death of God", which quickly finds an echo in Nietzsche's philosophy, and the notion of the "will to die". The will to die, which is an inverted form of Schopenhauer's will to live, is the principle of all existence ever since the origin of the world. Indeed, God[note 2] gave himself death, as it were, in creating the world, and since then, annihilation constitutes the only "salvation" of being, its only possibility of "redemption". For Mainländer, life itself has no value and the will becomes moral only when, moved by the knowledge of the superiority of nothingness over being, it deliberately aims at its suppression.[77] When the individual, by observing his own will, realizes that his salvation lies in his death, his will to live is transformed into a will to die. The will to life is in this perspective only the means used by the will to death to accomplish its goal.[55]: 202

In contrast to Schopenhauer, Mainländer supports a pluralistic conception of reality, called nominalism.[55]: 212 This ontological pluralism implies that individual wills are mortal, that the existence of an individual is limited in duration as well as in extension. The disappearance of an individual therefore leads to the silence of his will, being reduced to nothingness.[55]: 207 In Schopenhauer's metaphysics, on the contrary, individual wills were only manifestations of the essence of the world itself (the Will). Therefore, the disappearance of individuals could in no way extinguish the Will.[55]: 207 It would have been necessary to reduce the totality of the world to nothingness in order to do so. Mainländer's pluralist metaphysics, on the other hand, makes the annihilation of the Will possible, leading one to ascribe to death an essential negative power: that of making the essence of the world (understood as the simple sum of all individuals) disappear. Since non-being is superior to being, death provides a real benefit, even more important than all the others since it is definitive. This benefit is that of eternal peace and tranquility, which Mainländer calls "redemption",[55]: 206 thus taking up the lexicon of Christianity. Indeed, he interprets Christianity, in its mystical form, as a religion of renunciation and salvation, as a first revelation of his own philosophy.[55]: 208

Mainländer insists on the decisive significance of his ontological pluralism, with reality being nothing other than the existence of individual wills.[55]: 215 Rejecting Schopenhauer's metaphysical perspective, and with it the postulate of a cosmic universal will above and beyond the individual will, he asserts the necessarily "immanent", empirical and representational - and therefore non-metaphysical - character of knowledge, limited as it is to the field of individual consciousness. For him, each will, conceived as self-sufficient both from the point of view of knowledge and ontologically, is radically separated from the others.[55]: 215 Nevertheless, Mainländer admits, the natural sciences show that all the beings that make up the world are systematically interconnected, so that each thing depends on each other thing according to necessary laws.[55]: 215 Science thus seems to contradict the thesis that all Will is closed in on itself (and therefore free). This apparent contradiction can, however, be resolved, according to Mainländer, by introducing the dimension of time: in the beginning, before the beginning of time, there was a single, pure singularity, without any division.[55]: 216 At the beginning of time, the original unity of the world became fragmented and differentiated, thus beginning a process of division that has continued ever since. From the primitive unity of the world there remains the principle of the interconnection of things according to the laws of nature, but the underlying unity of things belongs to the past and therefore does not take away the individual character of the will.[55]: 216

It is to shed light on this passage from the conversion of the original unity to multiplicity that Mainländer introduces his tragic concept of the death of God.[55]: 216 In a vain prophecy, he declares: "God died and His death was the life of the world".[55]: 216 As Christianity had sensed through the figure of Christ, God - that is, the initial singularity - sacrificed himself by giving birth to the world.[55]: 216 Although we cannot really know the modalities of this begetting, it is possible, according to Mainländer, to have some idea of it by analogy with us. In this perspective, he constructs a remarkable anthropomorphic creation mythology in which God appears as a perfectly free and omnipotent individual, but who discovers with horror his own limitation in the very fact of his existence, which he cannot directly abolish, being the primary condition of all his powers. In this narrative, God, now inhabited by anguish, becomes aware that his present existence has a negative value, that it is therefore of less value than his non-existence.[55]: 217 He then decides to put an end to it, not directly, which is impossible for him, but by the mediation of a creation. By creating the world and then fragmenting it into a multitude of individual entities, he can progressively realize his desire for self-destruction.[55]: 217 It is this divine impulse towards self-destruction and annihilation that ultimately animates the whole cosmos, even if the impulse towards life (the Will to live) seems to dominate it at first sight.[55]: 218 Everything that exists, from the inorganic realm to the organic realm is ultimately governed by a fatal process of cosmic annihilation that translates on the physical level into entropy, and on the level of the living into struggle and conflict.[55]: 218 Mainländer considers this whole process to be ineluctable, like a Greek tragedy in which the destiny that one seeks to escape always ends up being fulfilled. In this macabre tragedy, the whole world is nothing more than "the rotting body of God".[55]: 218

Eduard von Hartmann

In his work entitled Philosophy of the Unconscious, the first edition of which appeared in 1869 and became famous already in the first years of its publication, Eduard von Hartmann, while presenting himself as the heir of Arthur Schopenhauer, replaces the Schopenhauerian principle of Will with his own principle of the Unconscious. The Unconscious, being a metaphysical rather than a psychological concept, is the invisible actor of history and hidden instigator of evolution,[78][page needed] including indissociably the irrational Will which pushes the world to exist (in Schopenhauer's sense), and the "Idea", in the Hegelian sense, which is the rational and organizing element of the world.[citation needed]

The Unconscious is both Will, Reason and the absolute all-embracing ground of all existence. Thus, being influenced by both Hegel and Schopenhauer, he affirms that the evolution of history goes in the direction of the development of the Idea and its prevalence over the (unconscious) Will. But it is indeed the Will, considered as an irrational principle, that has produced the world. The world is therefore inevitably full of evils and pains that cannot be eradicated, and the progressive development of the Idea means the progressive awareness of these evils and their inevitability, not their replacement by consciousness. "Cosmic suicide"[79] will therefore appear as the only final solution for the human race that has reached full consciousness, with the Unconscious evoking Reason and with its aid creating the best of all possible worlds, which contains the promise of its redemption from actual existence by the emancipation of Reason from its subjugation to the Will in the conscious reason of the enlightened pessimist.[80]

When the greater part of the Will in existence is so far enlightened by reason as to perceive the inevitable misery of existence, a collective effort to will non-existence will be made, and the world will relapse into nothingness, the Unconscious into quiescence. Although Von Hartmann is a pessimist, his pessimism is by no means unmitigated. The individual’s happiness is indeed unattainable either here and now or hereafter and in the future, but he does not despair of ultimately releasing the Unconscious from its sufferings. He differs from Schopenhauer in making salvation by the “negation of the Will-to-live” depend on a collective social effort and not on individualistic asceticism. Hartmann explains that there are three fundamental illusions about the value of life that must be overcome before humanity can achieve what he calls absolute painlessness, nothingness, or Nirvana.[81] The first of these illusions is the hope of good in the present, the confidence in the pleasures of this world, such as was felt by the Greeks. This is followed by the Christian transference of happiness to another and better life, to which in turn succeeds the illusion that looks for happiness in progress, and dreams of a future made worth while by the achievements of science. All alike are empty promises, and known as such in the final stage, which sees all human desires as equally vain and the only good in the peace of Nirvana.[82]

The conception of a redemption of the Unconscious also supplies the ultimate basis of Von Hartmann’s ethics. We must provisionally affirm life and devote ourselves to social evolution, instead of striving after a happiness which is impossible; in so doing we shall find that morality renders life less unhappy than it would otherwise be. Suicide, and all other forms of selfishness, are highly reprehensible. Epistemologically, Von Hartmann is a transcendental realist, who ably defends his views and acutely criticizes those of his opponents. His realism enables him to maintain the reality of Time, and so of the process of the world’s redemption.[82]

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche could be said to be a philosophical pessimist even though unlike Schopenhauer (whom he read avidly) his response to the tragic pessimistic view is neither resigned nor self-denying, but a life-affirming form of pessimism. For Nietzsche this was a "pessimism of the future", a "Dionysian pessimism."[83] Nietzsche identified his Dionysian pessimism with what he saw as the pessimism of the Greek pre-socratics and also saw it at the core of ancient Greek tragedy.[4]: 167 He saw tragedy as laying bare the terrible nature of human existence, bound by constant flux. In contrast to this, Nietzsche saw Socratic philosophy as an optimistic refuge of those who could not bear the tragedy any longer. Since Socrates posited that wisdom could lead to happiness, Nietzsche saw this as "morally speaking, a sort of cowardice ... amorally, a ruse".[4]: 172 Nietzsche was also critical of Schopenhauer's pessimism because, he argued that, in judging the world negatively, it turned to moral judgments about the world and, therefore, led to weakness and nihilism. Nietzsche's response was a total embracing of the nature of the world, a "great liberation" through a "pessimism of strength" which "does not sit in judgment of this condition".[4]: 178 He believed that the task of the philosopher was to wield this pessimism like a hammer, to first attack the basis of old moralities and beliefs and then to "make oneself a new pair of wings", i.e. to re-evaluate all values and create new ones.[4]: 181 A key feature of this Dionysian pessimism was "saying yes" to the changing nature of the world, this entailed embracing destruction and suffering joyfully, forever (hence the ideas of amor fati and eternal recurrence).[4]: 191 Pessimism for Nietzsche was an art of living that is "good for one's health" as a "remedy and an aid in the service of growing and struggling life".[4]: 199

Victorian pessimism

The pessimism of many of the thinkers of the Victorian era has been attributed to a reaction against the "benignly progressive" views of the Age of Enlightenment, which were often expressed by the members of the Romantic movement.[84] The works of Schopenhauer, particularly his concept of the primacy of the Will, has also been cited as a major influence on Victorian pessimism,[84] as well as Darwin's 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species.[85]

Several British writers of the time have been noted for the pervasive pessimism of their works, including Matthew Arnold, Edward FitzGerald, James Thomson, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Ernest Dowson, A. E. Housman, Thomas Hardy,[86] Christina Rossetti,[87] and Amy Levy;[88] the pessimistic themes particularly deal with love, fatalism, and religious doubt.[86] The poems of the Canadian poet Frederick George Scott have also been cited as an example of Victorian pessimism,[89] as have the poems of the American poet Edwin Arlington Robinson.[90]

During this period, artistic representations of nature transformed, from benevolent, uplifting and god-like, to actively hostile, competitive, or indifferent. Alfred, Lord Tennyson exemplified this change with the line "Nature, red in tooth and claw", in his 1850 poem In Memoriam.[85]

20th century

Albert Camus

In a 1945 article, Albert Camus wrote "the idea that a pessimistic philosophy is necessarily one of discouragement is a puerile idea."[91] Camus helped popularize the idea of "the absurd", a key term in his famous essay The Myth of Sisyphus. Like previous philosophical pessimists, Camus saw human consciousness and reason as that which "sets me in opposition to all creation".[92]: 51 For Camus, this clash between a reasoning mind which craves meaning and a "silent" world is what produces the most important philosophical problem, the "problem of suicide". Camus believed that people often escape facing the absurd through "eluding" (l'esquive), a "trickery" for "those who live not for life itself but some great idea that will transcend it, refine it, give it a meaning, and betray it".[92]: 8 He considered suicide and religion as inauthentic forms of eluding or escaping the problem of existence. For Camus, the only choice was to rebelliously accept and live with the absurd, for "there is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn." Camus illustrated his response to the condition of the absurd by using the Greek mythic character of Sisyphus, who was condemned by the gods to push a boulder up a hill for eternity, only for it to roll down again when it reached he top. Camus imagined Sisyphus while pushing the rock, realizing the futility of his task, but doing it anyway out of rebellion: "One must imagine Sisyphus happy."[92]: 123

Peter Wessel Zapffe

Peter Wessel Zapffe argued that evolution bestowed humans with a surplus of consciousness that allowed them to contemplate their place in the cosmos and yearn for justice and meaning together with freedom from suffering and death, while simultaneously being aware that nature or reality itself cannot satisfy those longings and spiritual demands.[93] For Zapffe, this was a tragic byproduct of evolution: full apprehension of humans' ill-fated and vulnerable situation in the universe would, according to him, cause them to fall into a state of "cosmic panic" or existential terror. Humans' knowledge of their predicament is thus repressed through the use of four mechanisms, conscious or not, which he names isolation, anchoring, distraction and sublimation.[94]

In his essay "The Last Messiah", he describes these four defense mechanisms as follows:[94]

- Isolation is "a fully arbitrary dismissal from consciousness of all disturbing and destructive thought and feeling".

- Anchoring is the "fixation of points within, or construction of walls around, the liquid fray of consciousness". The anchoring mechanism provides individuals with a value or an ideal to consistently focus their attention on. Zapffe also applied the anchoring principle to society and stated that "God, the Church, the State, morality, fate, the laws of life, the people, the future" are all examples of collective primary anchoring firmaments.

- Distraction is when "one limits attention to the critical bounds by constantly enthralling it with impressions". Distraction focuses all of one's energy on a task or idea to prevent the mind from turning in on itself.

- Sublimation is the refocusing of energy away from negative outlets, toward positive ones. The individuals distance themselves and look at their existence from an aesthetic point of view (e.g., writers, poets, painters). Zapffe himself pointed out that his produced works were the product of sublimation.

Terror Management Theory (TMT), a social and evolutionary psychology theory, is in accordance with Zapffe's view of human beings' higher cognitive abilities bringing them a form of existential anxiety that needs to be repressed or dealt with in some way.[95] According to TMT, such existential angst is born from the juxtaposition of human beings' awareness of themselves as merely transient animals groping to survive in a meaningless universe, destined only to die and decay.[96] For TMT, repression of such awareness is done through symbolic conceptions of reality that give meaning, order, and permanence to existence; provide a set of standards for what is valuable; and promise some form of either literal or symbolic immortality to those who believe in the cultural worldview and live up to its standards of value.[96]

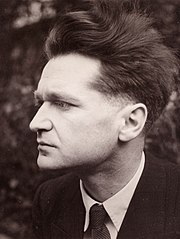

Emil Cioran

Emil Cioran's works are permeated with philosophical pessimism,[98][99] and deal with topics including failure, suffering, decay, existentialism and nihilism. Lacking interest in traditional philosophical systems and jargon, he rejects very early abstract speculation in favor of personal reflection and passionate lyricism. His first book, On the Heights of Despair, created as a product of Cioran's chronic insomnia, deals with "despair and decay, absurdity and alienation, futility and the irrationality of existence".[100] Cioran considered the human condition, the universe and life itself to be a failure: "life is a failure of taste which neither death nor even poetry succeeds in correcting."[101] William H. Gass described Cioran's The Temptation to Exist as "a philosophical romance on the modern themes of alienation, absurdity, boredom, futility, decay, the tyranny of history, the vulgarities of change, awareness as agony, reason as disease".[102]

Cioran's view of life's futility and the totality of its failure perhaps existed from a young age. In 1935, his mother told him that if she knew he would be so miserable, she would have aborted him. This prompted Cioran to later reflect, "I'm simply an accident. Why take it all so seriously?"[103]

Cioran wrote several works entirely in aphorisms; in reference to his choice to write aphoristically, Cioran stated:[104]

I only write this kind of stuff, because explaining bores me terribly. That's why I say when I've written aphorisms it's that I've sunk back into fatigue, why bother. And so, the aphorism is scorned by "serious" people, the professors look down upon it. When they read a book of aphorisms, they say, "Oh, look what this fellow said ten pages back, now he's saying the contrary. He's not serious." Me, I can put two aphorisms that are contradictory right next to each other. Aphorisms are also momentary truths. They're not decrees. And I could tell you in nearly every case why I wrote this or that phrase, and when. It's always set in motion by an encounter, an incident, a fit of temper, but they all have a cause. It's not at all gratuitous.

In The Trouble with Being Born, Cioran, through aphorisms, examined the problem of being brought into existence into a world which is difficult to fully accept, or reject, without one's consent.[105] His aphorisms in The Trouble with Being Born pack philosophy into single sentences. For example, Cioran summarizes the futility of life and espoused antinatalism by saying: "We have lost, being born, as much as we shall lose dying. Everything."[106]: 56

Cioran rejected suicide, as he saw suicide and death to be equally meaningless as life in a meaningless world. In The Trouble with Being Born, he contrasts suicide with his antinatalism: "It's not worth the bother of killing yourself, since you always kill yourself too late."[106]: 32 He did, however, argue that contemplating suicide could lead humans to live better lives.[107]

21st century

Julio Cabrera

According to Julio Cabrera's ontology, human life has a structurally negative value. Under this view, human life does not provoke discomfort in humans due to the particular events that happen in the lives of each individual, but due to the very being or nature of human existence as such. The following characteristics constitute what Cabrera calls the "terminality of being", in other words, its structurally negative value:[108]: 23–24

- The being acquired by a human at birth is decreasing (or "decaying"), in the sense of a being that begins to end since its very emergence, following a single and irreversible direction of deterioration and decline, of which complete consummation can occur at any moment between some minutes and around one hundred years.

- From the moment they come into being, humans are affected by three kinds of frictions: physical pain (in the form of illnesses, accidents, and natural catastrophes to which they are always exposed); discouragement (in the form of "lacking the will", or the "mood" or the "spirit", to continue to act, from mild taedium vitae to serious forms of depression), and finally, exposure to the aggressions of other humans (from gossip and slander to various forms of discrimination, persecution, and injustice), aggressions that we too can inflict on others, also submitted, like us, to the three kinds of friction.

- To defend themselves against (a) and (b), human beings are equipped with mechanisms of creation of positive values (ethical, aesthetic, religious, entertaining, recreational, as well as values contained in human realizations of all kinds), which humans must keep constantly active. All positive values that appear within human life are reactive and palliative; they do not arise from the structure of life itself, but are introduced by the permanent and anxious struggle against the decaying life and its three kinds of friction, with such struggle however doomed to be defeated by any of the mentioned frictions or by the progressive decline of one's being.

For Cabrera, this situation is further worsened by a phenomenon he calls "moral impediment", that is, the structural impossibility of acting in the world without harming or manipulating someone at some given moment.[108]: 52 According to him, moral impediment happens not necessarily because of a moral fault in us, but due to the structural situation in which we have been placed. The positive values that are created in human life come into being within a narrow and anxious environment where human beings are cornered by the presence of their decaying bodies as well as pain and discouragement, in a complicated and holistic web of actions, where it is difficult for our urgent need to build our own positive values not to end up harming the projects of other humans who are also trying to do the same, that is, build their own positive values.[108]: 54

David Benatar

David Benatar makes a case for antinatalism and philosophical pessimism in his works, arguing that procreation is morally indefensible in his book Better Never to Have Been and in The Human Predicament asserting that a pessimistic view of existence is more realistic and suitable than an optimistic one; he also takes care to distinguish pessimism from nihilism, arguing that the two concepts are not synonymous.[109]

To support his case for pessimism, Benatar mentions a series of empirical differences between the pleasures and pains in life, such as the most intense pleasures being short-lived (e.g. orgasms), whereas the most severe pains can be much more enduring;[110]: 77 the worst pains that can be experienced being worse than the best pleasures are good, offering as an example the thought experiment of whether one would accept "an hour of the most delightful pleasures in exchange for an hour of the worst tortures",[110]: 77 in addition to citing Schopenhauer, who made a similar argument, when asking his readers to "compare the feelings of an animal that is devouring another with those of that other";[111] the amount of time it may take for one's desires to be fulfilled (with some of our desires never being satisfied);[110]: 79 the quickness with which one's body can be injured, damaged, or fall ill, and the comparative slowness of recovery (with full recovery sometimes never being attained);[110]: 77–78 the existence of chronic pain, but the comparative non-existence of chronic pleasure;[110]: 77 the gradual and inevitable physical and mental decline to which every life is subjected through the process of ageing;[110]: 78–79 the effortless way in which the bad things in life naturally come to us, and the efforts one needs to muster in order to ward them off and obtain the good things;[110]: 80 the lack of a cosmic or transcendent meaning to human life as a whole (borrowing a term from Spinoza, according to Benatar our lives lack meaning from the perspective of the universe, that is, sub specie aeternitatis);[110]: 35–36 and, finally, Benatar concludes that, even if one argues that the bad things in life are in some sense necessary for human beings to appreciate the good things in life, or at least to appreciate them fully, he asserts that it is not clear that this appreciation requires as much bad as there is, and that our lives are worse than they would be if the bad things were not in such sense necessary:[110]: 85

Human life would be vastly better if pain were fleeting and pleasure protracted; if the pleasures were much better than the pains were bad; if it were really difficult to be injured or get sick; if recovery were swift when injury or illness did befall us; and if our desires were fulfilled instantly and if they did not give way to new desires. Human life would also be immensely better if we lived for many thousands of years in good health and if we were much wiser, cleverer, and morally better than we are.[110]: 82–83

Philosophical responses to the human condition

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

The responses to the predicament of the human condition by pessimists are varied. Some philosophers, such as Schopenhauer and Mainländer, recommend a form of resignation and self-denial (which they saw exemplified in Indian religions and Christian monasticism). Some thinkers tend to believe that "expecting the worst leads to the best." Rene Descartes believed that life was better if emotional reactions to "negative" events were removed. Eduard Von Hartmann asserted that with cultural and technological progress, the world and its inhabitants will reach a state in which they will voluntarily embrace nothingness. Others like Nietzsche, Leopardi, Julius Bahnsen and Camus respond with a more life-affirming view, which Nietzsche called a "Dionysian pessimism", an embrace of life as it is in all of its constant change and suffering, without appeal to progress or hedonistic calculus. Albert Camus indicated that the common responses to the absurdity of life are often: suicide, a leap of faith (as per Kierkegaard's knight of faith), or recognition, or rebellion. Camus rejected all but the last option as unacceptable and inauthentic responses.[92][page needed]

Regarding non-human animals

Aside from the human predicament, many philosophical pessimists also emphasize the negative quality of the life of non-human animals, criticizing the notion of nature as a "wise and benevolent" creator.[110]: 42–44 [112][113] In his 1973 Pulitzer Prize winning book The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker describes it thus:[114]

What are we to make of a creation in which the routine activity is for organisms to be tearing others apart with teeth of all types—biting, grinding flesh, plant stalks, bones between molars, pushing the pulp greedily down the gullet with delight, incorporating its essence into one's own organization, and then excreting with foul stench and gasses the residue. Everyone reaching out to incorporate others who are edible to him. The mosquitoes bloating themselves on blood, the maggots, the killer-bees attacking with a fury and a demonism, sharks continuing to tear and swallow while their own innards are being torn out—not to mention the daily dismemberment and slaughter in "natural" accidents of all types: an earthquake buries alive 70 thousand bodies in Peru, automobiles make a pyramid heap of over 50 thousand a year in the U.S. alone, a tidal wave washes over a quarter of a million in the Indian Ocean. Creation is a nightmare spectacular taking place on a planet that has been soaked for hundreds of millions of years in the blood of all its creatures. The soberest conclusion that we could make about what has actually been taking place on the planet for about three billion years is that it is being turned into a vast pit of fertilizer. But the sun distracts our attention, always baking the blood dry, making things grow over it, and with its warmth giving the hope that comes with the organism's comfort and expansiveness.

The theory of evolution by natural selection can be said to justify a form of philosophical pessimism based on a negative evaluation of the lives of animals in the wild. In 1887, Charles Darwin expressed a feeling of revolt at the notion that God's benevolence is limited, stating: "for what advantage can there be in the sufferings of millions of the lower animals throughout almost endless time?"[115] The animal activist and moral philosopher Oscar Horta argues that because of evolutionary processes, not only is suffering in nature inevitable, but that it actually prevails over happiness.[116] For evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, nature is in no way benevolent. He argues that what is at stake in biological processes is nothing more than the survival of DNA sequences of genes.[117]: 131 Dawkins also asserts that as long as the DNA is transmitted, it does not matter how much suffering such transmission entails and that genes do not care about the amount of suffering they cause because nothing affects them emotionally. In other words, nature is indifferent to unhappiness, unless it has an impact on the survival of the DNA. Although Dawkins does not explicitly establish the prevalence of suffering over well-being, he considers unhappiness to be the "natural state" in wild animals:[117]: 131–132

The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. During the minute it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive; others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear; others are being slowly devoured from within by rasping parasites; thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst and disease. It must be so. If there is ever a time of plenty, this very fact will automatically lead to an increase in population until the natural state of starvation and misery is restored ... In a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won't find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.

In popular culture

The character of Rust Cohle in the first season of the television series True Detective is noted for expressing a philosophically pessimistic worldview;[118][119] the creator of the series was inspired by the works of Thomas Ligotti, Emil Cioran, Eugene Thacker and David Benatar when creating the character.[120]

See also

Notes

- ^ Beiser reviews the commonly held position that Schopenhauer was a transcendental idealist and he rejects it: "Though it is deeply heretical from the standpoint of transcendental idealism, Schopenhauer's objective standpoint involves a form of transcendental realism, i.e. the assumption of the independent reality of the world of experience."[55]: 40

- ^ In Mainländer's naturalistic philosophy, "God" is a metaphor for a kind of initial singularity from which the expansion of the universe began.

References

- ^ For discussions around the views and arguments of philosophical pessimism see:

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1966). The World as Will and Representation. Vol. 1. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-21761-1.

- Benatar, David (2017). The Human Predicament: A Candid Guide to Life's Biggest Questions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-063381-3.

- Ligotti, Thomas (2011). The Conspiracy Against the Human Race: A Contrivance of Horror. New York, NY: Hippocampus Press. ISBN 978-0-9844802-7-2. OCLC 805656473.

- Saltus, Edgar (2012) [1885]. The Philosophy of Disenchantment. Project Gutenberg.

- Coates, Ken (2014). Anti-Natalism: Rejectionist Philosophy from Buddhism to Benatar. First Edition Design Pub. ISBN 978-1-62287-570-2.

- Lugt, Mara van der (2021). Dark Matters: Pessimism and the Problem of Suffering. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-20662-2.

- Sully, James (1877). Pessimism: A History and a Criticism. London: Henry S. King & Co.

- ^ Sorgner, Stefan Lorenz; Fürbeth, Oliver, eds. (2011). Music in German Philosophy: An Introduction. Translated by Gillespie, Susan H. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-226-76839-7.

- ^ Miller, Ed L. (2015). God and Reason, Second Edition: An Invitation to Philosophical Theology (2nd ed.). Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4982-7954-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dienstag, Joshua Foa (2009). Pessimism: Philosophy, Ethic, Spirit. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-6911-4112-1.

- ^ a b Beiser, Frederick C. (2016). Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860-1900 (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-876871-5. OCLC 929590292.

The philosophical discussion of pessimism in late 19th-century Germany shows a remarkable unanimity about its central thesis. According to all participants in this discussion, pessimism is the thesis that life is not worth living, that nothingness is better than being, or that it is worse to be than not be.

- ^ Smith, Cameron (December 17, 2014). Philosophical Pessimism: A Study In The Philosophy Of Arthur Schopenhauer (Masters thesis). Georgia State University. p. 2.

- ^ For discussions of suicide and antinatalism in the context of philosophical pessimism see:

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1913). "On the Sufferings of the World". Studies in Pessimism. Translated by Saunders, Thomas Bailey. London: George Allen & Company. p. 15.

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1913). "On Suicide". Studies in Pessimism. Translated by Saunders, Thomas Bailey. London: George Allen & Company. p. 48.

- Benatar, David (2013). "Still Better Never to Have Been: A Reply to (More of) My Critics". The Journal of Ethics. 17 (1/2, p. 148): 121–151. doi:10.1007/s10892-012-9133-7. S2CID 170682992.

- Ligotti, Thomas (2011). The Conspiracy Against the Human Race: A Contrivance of Horror. New York, NY: Hippocampus Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-9844802-7-2. OCLC 805656473.

- Coates, Ken (2014). Anti-Natalism: Rejectionist Philosophy from Buddhism to Benatar. First Edition Design Pub. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-62287-570-2.

- ^ Sully, James (1877). Pessimism: A History and a Criticism. London: Henry S. King & Co. p. 38.

- ^ Ligotti, Thomas (2011). The Conspiracy Against the Human Race: A Contrivance of Horror. New York, NY: Hippocampus Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-9844802-7-2. OCLC 805656473.

- ^ Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, translated from the Pali version by Bhikkhu Bodhi.

- ^ Preus, Anthony (February 12, 2015). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Philosophy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 184. ISBN 9781442246393.

- ^ Clayman, Dee L. (February 15, 2014). Berenice II and the Golden Age of Ptolemaic Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780195370898.

- ^ Guyau, Jean-Marie (1878). Le Morale D'Épicure Et Ses Rapports Avec Les Doctrines Cntemporaines (in French). Librairie Germer Bailliere. p. 117.

- ^ "Ecclesiastes: Old Testament". Britannica. 1998-07-20. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ^ Ecclesiastes 1:1–9

- ^ Sneed, Mark R. (2012). The Politics of Pessimism in Ecclesiastes: A Social-Science Perspective. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-1-58983-635-8.

- ^ Ecclesiastes 2:13–17

- ^ Ecclesiastes 4:1–3

- ^ Sexton, Jared (2019). "Affirmation in the Dark: Racial Slavery and Philosophical Pessimism". The Comparatist. 43 (1): 90–111. doi:10.1353/com.2019.0005. ISSN 1559-0887.

- ^ Dell, Katharine J.; Kynes, Will; Mein, Andrew; Camp, Claudia V. (2016). Reading Ecclesiastes Intertextually. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-0-567-66790-8.

- ^ Bottéro, Jean (1995). Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods. University of Chicago Press. pp. 260–261. ISBN 978-0-226-06727-8.

- ^ John 15:19

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hutin, Serge (1978) [1958]. "Chapter 2: Misère de l'homme". Les gnostiques. Que sais-je? (in French) (4th ed.). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. OCLC 9258403.

- ^ Dorandi, Tiziano (1999), Algra, Keimpe; Barnes, Jonathan; Mansfeld, Jaap; Schofield, Malcolm (eds.), "Chronology", The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 47, doi:10.1017/chol9780521250283.003, ISBN 978-0-521-25028-3, retrieved 2022-12-01

- ^ Hadot, Pierre. "Cyrénaïque École" [Cyrenaic School]. Encyclopædia Universalis (in French). Retrieved 2022-12-29.

- ^

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. § 86.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. § 86.

- ^ a b Laertius, Diogenes (2018). The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Translated by Yonge, Charles Duke. Project Gutenberg.

- ^

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

- ^ Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones i. 34

- ^ Rozveh, Nasser Ghasemi (2013). "The Comparative Survey of Pessimism in Abul Ala Al-Maarri and Hakim Omar Khayyam Poems" (PDF). Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research. 3 (3): 405–413. ISSN 2090-4304.

- ^ "Al-Maʿarrī". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Smith, Hilary Dansey (1988). "The Ages of Man in Baltasar Gracián's "Criticón"". Hispanófila (94): 35–47. ISSN 0018-2206.

- ^ a b Herdt, Jennifer A. (2015). Putting On Virtue: The Legacy of the Splendid Vices. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-226-32719-8.

- ^ Duff, E. Grant (2016-03-26). "Balthasar Gracian". The Fortnightly Review. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Cartwright, David E. (2005). Historical Dictionary of Schopenhauer's Philosophy. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-8108-5324-9. OCLC 55955168.

- ^ "Blaise Pascal". The School of Life. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Huisman, Denis (2002). Histoire de la philosophie française [History of French Philosophy] (in French). Paris: Perrin. OCLC 473902784.

- ^ Pascal 1669 (fragment n° 133), Denis Huisman, Histoire de la philosophie française, Paris, Perrin, 2002, p. 199.

- ^ Pascal 1669 (fragment n° 414), Denis Huisman, Histoire de la philosophie française, Paris, Perrin, 2002, p. 199.

- ^ Pascal 1669 (fragment n° 200), Denis Huisman, Histoire de la philosophie française, Paris, Perrin, 2002, p. 200.

- ^ Havens, George R. (1928). "Voltaire's Marginal Comments Upon Pope's Essay on Man". Modern Language Notes. 43 (7): 429–439. doi:10.2307/2914234. ISSN 0149-6611. JSTOR 2914234.

- ^ a b Durant, Will; Durant, Ariel (1935). "The Theology of Earthquakes". The Age of Voltaire: A History of Civlization in Western Europe from 1715 to 1756. The Story of Civilization. Vol. IX. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 720–724.

- ^ Woods, David Bather (2021-02-24). "The promise of pessimism". Institute of Art and Ideas. Retrieved 2022-09-27.

- ^ Yendley, David. "Is Candide a Totally Pessimistic Book?". French Literature Notes 2. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- ^ Rennie, Nicholas (2005). Speculating on the Moment: The Poetics of Time and Recurrence in Goethe, Leopardi, and Nietzsche. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag. p. 141. ISBN 978-3-89244-968-3. OCLC 61430097.

- ^ Michael J. Subialka (2021). Modernist Idealism: Ambivalent Legacies of German Philosophy in Italian Literature. University of Toronto Press. p. 264. ISBN 9781487528652. OCLC 1337856720

- ^ Leopardi, Giacomo (2013). Caesar, Michael; D'Intino, Franco (eds.). Zibaldone. Translated by Baldwin, Kathleen; Dixon, Richard; Gibbons, David; Goldstein, Ann; Slowey, Gerard; Thom, Martin; Williams, Pamela (1st ed.). New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-374-29682-7. OCLC 794973811.

- ^ Klosko, George (1987). "Socrates on Goods and Happiness". History of Philosophy Quarterly. 4 (3): 251–264. ISSN 0740-0675.

- ^ a b Leopardi, Giacomo (1983). "Dialogue between Timander and Eleander". Operette Morali: Essays and Dialogues. Translated by Cecchetti, Giovanni. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04928-4.

- ^ Leopardi, Giacomo (2013). Caesar, Michael; D'Intino, Franco (eds.). Zibaldone. Translated by Baldwin, Kathleen; Dixon, Richard; Gibbons, David; Goldstein, Ann; Slowey, Gerard; Thom, Martin; Williams, Pamela (1st ed.). New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 1997. ISBN 978-0-374-29682-7. OCLC 794973811.

My philosophy makes nature guilty of everything, and by exonerating humanity altogether, it redirects the hatred, or at least the complaint, to a higher principle, the true origin of the ills of living beings, etc. etc.

- ^ Leopardi, Giacomo (1882). "Dialogue Between Nature and an Icelander". Essays and Dialogues. Translated by Edwardes, Charles. London: Trübner & Co. p. 79.

- ^ Leopardi, Giacomo (1882). "Dialogue Between Christopher Columbus And Pietro Gutierrez". Essays and Dialogues. Translated by Edwardes, Charles. London: Trübner & Co.

- ^ Leopardi, Giacomo (2018). Thoughts. Translated by Nichols, J. G. Richmond: Alma Books. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7145-4826-5.

- ^ Arriagada, Ignacio Moya (2018). Pessimismo Profundo (in Spanish). Chile: Editorial Librosdementira Ltda. p. 35. ISBN 9789569136566.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Beiser, Frederick C. (2016). Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860-1900 (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-876871-5. OCLC 929590292.

- ^

Beiser, Frederick C. (2016). Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860-1900 (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-876871-5. OCLC 929590292.

The prevalence of pessimism in Germany after the 1860s was due chiefly to the influence of one man: Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860). It was Schopenhauer who made pessimism a systematic philosophy, and who transformed it from a personal attitude into a metaphysics and worldview.

- ^ Coates, Ken (2014). Anti-Natalism: Rejectionist Philosophy from Buddhism to Benatar. First Edition Design Pub. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-62287-570-2.

However despite a long history of literary allusions to the ills of existence, systematic philosophies, especially secular ones, which argue the case against existence are few and far between. They only date back to the 19th century, with Schopenhauer and to a lesser extent Eduard von Hartmann as the outstanding figures.

- ^ Saltus, Edgar (2012) [1885]. The Philosophy of Disenchantment. Project Gutenberg. p. 2.

In stating that this view of life is of distinctly modern origin, it should be understood that it is so only in the systematic form which it has recently assumed, for individual expressions of discontent have been handed down from remote ages.

- ^ Lugt, Mara van der (2021). Dark Matters: Pessimism and the Problem of Suffering. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-691-20662-2.

Schopenhauer is undoubtedly a key figure in pessimism, and arguably the thinker who turns pessimism into a coherent philosophical tradition for the first time.

- ^ a b Schopenhauer, Arthur (1966). The World as Will and Representation. Book IV, § 57. Vol. 1. Translated by Payne, E. F. J. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-21761-1. OCLC 276339.

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur (1966). "Chapter XIX - On the Primacy of the Will in Self-Consciousness". The World as Will and Representation. Vol. 2. Translated by Payne, E. F. J. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-21762-8. OCLC 500710082.

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur (1966). The World as Will and Representation. Book IV, § 56. Vol. 1. Translated by Payne, E. F. J. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-21761-1. OCLC 276339.

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur (1913). "The Vanity of Existence". Studies in Pessimism. Translated by Saunders, Thomas Bailey. London: George Allen & Company. p. 38.

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur (1966). The World as Will and Representation. Book II, § 27. Vol. 1. Translated by Payne, E. F. J. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-21761-1. OCLC 276339.

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur (1913). "On the Sufferings of the World". Studies in Pessimism. Translated by Saunders, Thomas Bailey. London: George Allen & Company.