Mokrani Revolt

| Mokrani Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of French conquest of Algeria | |||||||

Tribes under the Mokrani revolt. Source : Djilali Sari, L'insurrection de 1871, SNED, Alger, 1972, p.29. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Algerian rebels: Algerian peasantry |

France: Native auxiliaries | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 100,000 Kabyle cavalry, and 100,000 other fighters[1] | Army of Africa (86,000 men) plus native auxiliaries | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ≈ 20,000 dead (at least 2,000 summarily executed)[2] | 2,686 dead[3] | ||||||

The Mokrani Revolt (Template:Lang-ar; Template:Lang-ber) was the most important local uprising against France in Algeria since the conquest in 1830.

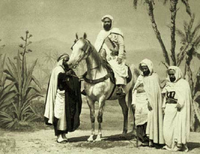

The revolt broke out on March 16, 1871, with the uprising of more than 250 tribes, around a third of the population of the country. It was led by the Kabyles of the Biban mountains commanded by Cheikh Mokrani and his brother Bou-Mezrag el-Mokrani, as well as Cheikh El Haddad, head of the Rahmaniyya Sufi order.

Background

Cheikh Mokrani

Cheikh Mokrani (full name el-Hadj-Mohamed el-Mokrani) and his brother Boumezrag (full name Ahmed Bou-Mezrag) came from a noble family - the Ait Abbas dynasty (a branch of the Hafsids of Béjaïa), the Amokrane, rulers, since the sixteenth century of the Kalâa of Ait Abbas in the Bibans and of the Medjana region.[4] In the 1830s, their father el-Hadj-Ahmed el-Mokrani (d. 1853), had chosen to form an alliance with the French : he allowed the Iron Gates expedition in 1839, becoming thus khalifa of the Medjana under the supervision of French authorities.[5] This alliance quickly proved to be a subordination - a decree of 1845 abolished the khalifalik of Medjana so that when Mohamed succeeded his father, his title was no more than “Bachagha” (Template:Lang-tr = chief commander), and was part of the administration of the Bureaux arabes.[6]: 35 During the hardships of 1867, he gave his personal guarantee, at the request of the authorities, for important loans.

The context

The background of the revolt is as important as the revolt itself. In 1830, French army took over Algiers. After that, France colonized the country, setting up its own administration all over Algeria. Shortly after 1830, a resistance rose up, led by Abd al-Kader, which lasted till 1847. French administrations and the France government decided to repress this movement which impacted both people and agriculture. The late 1860s were hard for the people of Algeria: between 1866 and 1868 they lived through drought, exceptionally cold winters, an epidemic of cholera and an earthquake. More than 10% of the Kabyle population died during this period.[1] Thus, at the end of the 1860s, Algeria was exhausted and the demography at its worst. To sum up all those events, on March 9, 1870, the French government decided to put a civilian regime in Algeria, which gave more advantages to French colonizers. In 1870, the creditors demanded to be repaid and the French authorities reneged on the loan on the pretext of the Franco-Prussian War, leaving Mohamed forced to pawn his own possessions. On June 12, 1869, Marshall MacMahon, the Governor General, advised the French government that “the Kabyles will stay peaceful as long as they see no possibility of driving us out of their country.”[7]

Under the French Second Republic, the country was governed by a Governor General and a large proportion was "military territory".[8][9] There were tensions between the French colonists and the army; the former favouring the abolition of the military territory as being too protective of the native Algerians.[10] Eventually, on March 9, 1870, the Corps législatif passed a law which would end the military regime in Algeria.[11] When Napoleon III fell and the Third French Republic was proclaimed, the Algerian question fell under the remit of the new Justice Minister, Adolphe Crémieux, and not, as previously, under the Minister of War. At the same time, Algeria was experiencing a period of anarchy. The settlers, hostile to Napoleon III and strongly Republican, took advantage of the fall of the Second Empire to push forward their anti-military agenda. Real authority devolved to town councils and local defence committees, and their pressure resulted in the Crémieux Decree.

Meanwhile, on September 1, 1870, the French army was defeated by the Prussian army in Sedan, and lost the French part of Alsace-Lorraine. The fact that France was at this time defeated by another country brought hope to Algerians. Indeed, the news of the French defeat on its border was spread thanks to the paper news. Then, Algerian protests began in public places, and in the South of Algeria, people committees were established to organize the revolt.

Revolt's origins

Algeria's inhabitants and the Second Empire

A number of causes have been suggested for the Mokrani revolt. There was a general dissatisfaction among Kabyle notables because of the steady erosion of their authority by the colonial authorities. At the same time, ordinary people were concerned about the imposition of civilian rule on March 9, 1870, which they interpreted as imposing domination by the settlers, with encroachments on their land and loss of autonomy.[12]

The Cremieux decree

The Cremieux Decree of October 24, 1870, which gave French nationality to Algerian Jews was possibly another cause of the unrest.[6]: 119 [13] However some historians view this as doubtful, pointing out that this story only started to spread after the revolt was over.[14] This explanation of the revolt was particularly widespread among French antisemites.[15] News of the insurrectionary Paris commune also played a part.[16] Indeed, from March 18 until May 28, 1871, Paris was under the Commune, which was an autonomous commune administered under direct democracy principles. This Commune was also the hope to found a social and democratic Republic. Thus, the episode of the Paris Commune resonated in Algeria as a new possibility to take over the French administration established in Algeria.

Several months before the start of the insurrections, Kabyle village communities multiply gatherings of electing village assemblies ("tiǧmaʿīn", Arabic "ǧamāʿa") despite the colonial authorities having banned them from doing so. It must be emphasised that those "ǧamāʿa" were managing bodies to the population, therefore an obstacle to French policy . On social matters those assemblies would decide rules for the community. They were composed with a president "amin", a treasurer named a "ukil" and some men of the village elected to verify the members (patrilineage) or because they are really elder.

The first signs of actual revolt appeared in the mutiny of a squadron of the 3rd Regiment of Spahis in January 1871. The spahis (Muslim cavalry troopers in the French Army of Africa) refused to be sent to fight in metropolitan France,[17] claiming that they were only required to serve in Algeria. This mutiny began in Moudjebeur, near Ksar Boukhari on January 20, 1871, spread to Aïn Guettar (in the region of modern Khemissa, near Souk Ahras) on January 23, 1871, and soon reached El Tarf and Bouhadjar.[18]

Cheikh Mokrani's dissidence

The mutiny at Aïn Guettar involved the mass desertion of several hundred men and the killing of several officers. It took on a particular significance for the Rezgui family, whose members maintained that France, recently defeated by the Prussians, was a spent force and that now was the time for a general uprising. The Hanenchas responded to this call, killing fourteen colonists in their territory; Souk Ahras was besieged from 26th to 28 January, before being relieved by a French column, who then put down the insurgency and condemned five men to death.[18]

Mokrani submitted his resignation as bachagha in March 1871, but the army replied that only the civil government could now accept it. In reply, Mokrani wrote to General Augeraud, subdivisional commander at Sétif:[19]

"You know the matter which puts me at odds with you; I can only repeat to you what you already know - I do not wish to be the agent of the civil government..... I am preparing myself to fight you; today let each of us take up his rifle."[13]

The revolt spreads

The spahi mutiny was reignited after March 16, 1871, when Mokrani took charge of it.[13] On March 16, Mokrani led six thousands men in an assault on Bordj Bou Arreridj.[20] On April 8, French troops regained control of the Medjana plain. The same day, Si Aziz, son of Cheikh al-Haddad, head of the Rahmaniyya order, proclaimed a holy war in the market of Seddouk.[13] Soon 150,000 Kabyles rose,[21] as the revolt spread along the coast first, then into the mountains to the east of the Mitidja and as far as Constantine. It then spread to the Belezma mountains and linked with local insurrections all the way down to the Sahara desert.[22] As they spread towards Algiers itself, the insurgents took Lakhdaria (Palestro), 60 km east of the capital, on the 14th of April. By April, 250 tribes had risen, or nearly a third of Algeria's population. One hundred thousand “mujahidin”, poorly armed and disorganised, were launching random raids and attacks.[12]

French counterattack

The military authorities brought in reinforcements for the Army of Africa; Admiral de Gueydon, who took over as Governor General on March 29, replacing Special Commissioner Alexis Lambert, mobilised 22,000 soldiers.[1] Advancing from Palestro towards Algiers, the rebels were stopped at Boudouaou (Alma) on April 22, 1871, by colonel Alexandre Fourchault under the command of General Orphis Léon Lallemand; on May 5,[1] Mohamed el-Mokrani died fighting at Oued Soufflat, halfway between Lakhdaria (Palestro) and Bouira in an encounter with the troops of General Félix Gustave Saussier.[20]

On 25 April, the Governor General declared a state of siege.[23] Twenty columns of French troops marched on Dellys and Draâ El Mizan. Cheikh al-Haddad and his sons were captured on July 13, after the battle of Icheriden.[24] The revolt only faded after the capture of Bou-Mezrag, Cheikh Mokrani's brother, on January 20, 1872.[25]

Repression

During the fighting, around 100 European civilians died, along with an unknown number of Algerian civilians.[1] After fighting ceased, more than 200 Kabyles were interned[26] and others deported to Cayenne[26] and New Caledonia, where they were known as Algerians of the Pacific.[27] Bou-Mezrag Mokrani was condemned to death by a court in Constantine on March 27, 1873.

The Kabylie region was subjected to a collective fine of 36 millions francs, and 450,000 hectares of land were confiscated and given to new settlers, many of whom were refugees from Alsace-Lorraine,[26][1] especially in the region of Constantine. The repression and confiscations forced a lot of Kabyles to leave the country.[1]

Chronology of battles

| N° | Battle | Current location | From | To | Leaders | Zawiyas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Battle of Bordj Bou Arréridj | Bordj Bou Arréridj | March 16, 1871 | June 2, 1871 | ||

| 02 | Battle of Palestro | Lakhdaria | April 14, 1871 | May 25, 1871 | ||

| 03 | Battle of Laazib Zamoum | Naciria | April 17, 1871 | May 22, 1871 | ||

| 04 | Battle of Bordj Menaïel | Bordj Menaïel | April 18, 1871 | May 18, 1871 | ||

| 05 | Battle of the Issers | Issers | April 18, 1871 | May 13, 1871 | ||

| 06 | Battle of the Col des Beni Aïcha | Thenia | April 19, 1871 | May 8, 1871 | ||

| 07 | Battle of Alma | Boudouaou | April 19, 1871 | April 23, 1871 |

Trial of rebel leaders

After the end of the hostilities of the insurrection of Cheikh Mokrani, the Algerian rebel leaders who were captured alive appeared before the Assize Court of Algiers on December 27, 1872, on a count of indictment and an act of accusation linked to the sacking of the French colonies, the assassinations, fires and looting which sparked heated debates on this extremely important affair.[28]

Several criminal charges weighed on each of the offender who all, without exception, had taken part in the insurrection. The prosecution of the court made charges which weighed on each of the accused for the crimes alleged against these main leaders and leaders of the 1871 insurrection.

The list of these incarcerated rebel leaders is as follows:

- Cheikh Boumerdassi (1818-1874) alias "Mohamed ben Hamou ben Abdelkrim".

- Abdelkader Boumerdassi (born 1837) alias "Abdelkader ben Hamou ben Abdelkrim".

- Omar ben Zamoum[29]

- Mohamed Saïd Oulid ou Kassi (Oukaci)

- Hadj Ahmed ben Dahman

- Si Saïd ben Ali

- Si Saïd ben Ramdan

- Mohamed ben M'Ra (Merah)

- Hadj Mohamed ben Moussa

- Mohamed Amzian Oulid Yahia

- Mohamed ben Bouzid

- Moussa ben Ahmed ben Mohamed

- Saïd ben Ahmed ben Mohamed

- Ali ben Haoussin

- Amar bel Abbas

- Ahmed ben Zoubir

- Ahmed Khoia ben Mohamed

- Mohamed ben Aissa

- Mohamed ben Belkassem

- Ahmed ben Sliman

- Mohamed bel Aid

- Mohamed ben Yahia

- Ali N'Amara ou el Hadj Saïd

- Si Saïd ben Mohamed

- Omar ben Haminided

- Ahmed Oulid el hadj Ali

- Belgassem ben Gassem

- Mohamed ben Lounés

- Ali ben Amran

- Ahmed ben Amar

- Hassein el Achebeb

- Smaîn ben Omar

- Si Mohamed ou El Hadj ou Alali

- Mohamed bou Bahia

A long list was then enumerated of the names of other subordinate rebel Algerian leaders and natives who participated in the Alma and Palestro massacres.

After reading the indictment, including the whole so-called Palestro affair, which lasted about an hour and a half, the president of the assize court urged the jurors to follow on the notebook that was given to them, and where the name of each offender was written at the top of a page, the individual examination which will be carried out and to take notes due to the length of the debates.

Deportation to New Caledonia

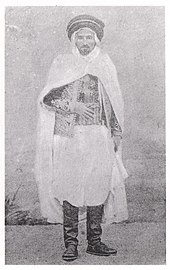

The leaders of the Mokrani Revolt after their capture and trial in 1873 were either executed, subjected to forced labor, or deported and exiled to the Pacific and New Caledonia.[30][31]

A convoy of 40 Kabyle insurrectional leaders was undertaken on the ship La Loire on June 5, 1874, towards the L'Île-des-Pins for deportation. They were the symbols of Algerian resistance against the French occupation.[32]

The specialist in history Malika Ouennoughi drew up a list of these 40 deportees, whose names follow:[33]

- Cheikh Boumerdassi, born in 1818 at Ouled Boumerdès, was a marabout, with the matricule: 1301.

- Ahmed ben Ali Seghir ben Mohamed Ouallal, born in 1854 at Baghlia, was a farmer, with the matricule: 852.

- Ahmed Kerbouchene, born in 1829 at Larbaâ Nath Irathen, was a farmer, with the matricule: 883.

- Ahmed ben Mohamed ben Barah, born in 1829 at Dar El Beïda, was a farmer, with the matricule: 859.

- Ahmed ben Belkacem ben Abdallah, born in 1822 at Oued Djer, was an indigene, with the matricule: 1306.

- Ahmed ben Ahmed Bokrari, born in 1838 at Bou Saâda, was an farmer, with the matricule: 857.

- Abdallah ben Ali ben Djebel, born in 1844 at Guelma, was a spahi, with the matricule: 803.

- Ahmed ben Salah ben Amar ben Belkacem, born in 1809 at Souk Ahras, was an caïd, with the matricule: 854.

On May 18, 1874, the leaders of the Mokrani Revolt were embarked at the Port of Brest in the 9th convoy of deportees from the ship La Loire placed under the orders of captain Adolphe Lucien Mottez (1822-1892).[34]

They numbered 50 Algerian deportees, and were reinforced with 280 other French convicts from the jails of Fort Quélern, and at their head the marabout Cheikh Boumerdassi.[35]

This ship arrived on June 7, at the anchorage of the port of Île-d'Aix, where it embarked 700 passengers, including 40 women, and 320 other French deportees.[36]

On June 9, he left for Nouméa, and it was therefore the 9th convoy of deportees that left France to then stop on June 23, in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, to arrive in Nouméa on October 16, 1874.

After a last stopover in Santa Catarina Island, La Loire arrives in Nouméa on October 16, 1874, after a journey of 133 days.[37]

There will be around 5 deaths at sea and on November 10, of the same year, the ship "La Loire" left Nouméa to return to France after having disembarked the convicts from Kabylie.[38]

On the 40 or 50 Algerians mentioned, 39 were destined for simple deportation to the L'Île-des-Pins, and only one of them for deportation to a fortified enclosure.

On the 300 convoys in the convoy, 250 suffered from scurvy, and will die in the weeks following their arrival in New Caledonia according to Roger Pérennès.[39][40]

In Mémoires d'un Communard, Jean Allemane evokes a deadly epidemic of dysentery which decimated the transported people that La Loire had just landed, and who were buried in large numbers.[41][42]

Begun at dawn, the burial of the corpses was a task which often did not end until nightfall, and the men who had died of dysentery presented a morbid spectacle.[43][44]

More than two hundred convicts who had come by the Loire died almost immediately after their disembarkation.[45]

However Louis-José Barbançon reports that on the civil status registers of the Bagne of L'Île-des-Pins, which were very well kept, only 28 deaths of convicts who came by "La Loire" appeared in the 6 months after arrival of the ship.[46][47]

See also

- List of participants in Mokrani Revolt

- Zawiyas in Algeria

- Rahmaniyya

- Zawiyet Sidi Boumerdassi

- Cheikh Boumerdassi

- Fort Quélern

- French ship Prince Jérôme

Bibliography

- Bozarslan, Hamit. Sociologie politique du Moyen-Orient, Collection Repères, La Découverte, 2011.

- Brett, Michael. “Algeria 1871–1954 - Histoire de l’Algérie Contemporaine. Vol. 11: De L’insurrection de 1871 Au Déclenchement de La Guerre de Libération (1954). By Charles-Robert Ageron. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1979. Pp. 643. No Price Stated.” Journal of African history 22.3 (1981): 421–423. Web.

- Brett, Michael. “Algeria 1871–1954.” The Journal of African History 1981: 421–423.

- De Grammont, H.-D. “RINN, Histoire de l’insurrection de 1871 en Algérie.” Revue Critique d’Histoire et de Littérature 25.2 (1891): 301–. Print.

- De Peyerimhoff, Henri. “La colonisation officielle en Algérie de 1871 à 1895.” Revue Économique Française 1928: 369–. Print.

- De Peyerimhoff, Henri de, and Comité Bugeaud. La colonisation officielle de 1871 à 1895 : [rapport à M. Jonnart, gouverneur général de l’Algérie]. Paris Tunis: Société d’éditions géographiques, maritimes et coloniales Comité Bugeaud, 1928. Print.

- Jalla, Bertrand. “L’autorité judiciaire dans la répression de de 1871 en Algérie.” Outre-mers (Saint-Denis) 88.332 (2001): 389–405. Web.

- Merle, Isabelle . “Algérien en Nouvelle-Calédonie : Le destin calédonien du déporté Ahmed Ben Mezrag Ben Mokrani.” L’année du Maghreb 20 (2019): 263–281. Web.

- Mottez, Adolphe Lucien (1875). Deux Expériences faites à bord de la Loire pendant un voyage en Nouvelle-Calédonie. 1874-1875. p. 83.

- Lewis, Bernard. Histoire du Moyen-Orient, Albin Michel, 2000.

- Robin, Joseph, Mahé, Alain. L’insurrection de la Grande Kabylie en 1871. Saint-Denis: Éditions Bouchène, 2018. Print.

- Sicard, Christian. La Kabylie en feu : Algérie 1871. Paris: Georges Sud, 2013. Print.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Zancarini-Fournel, Michelle (2016). "Les communes, le peuple au pouvoir?". In Éditions La Découverte (ed.). Les luttes et les rêves (in French). Paris. p. 375. ISBN 9782355220883.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Catalogue de l'exposition L'Algérie à l'ombre des armes, 1830 – 1962. Casterman BD. March 26, 2010. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-2-203-06168-2.

- ^ Yacono, X (April 2004). "Kabylie: L'insurrection de 1871". Encyclopédie Berbère (26): 4022–4026. doi:10.4000/encyclopedieberbere.1410. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ Féraud, Laurent-Charles (2011). Histoire Des Villes de la Province de Constantine: Sétif, Bordj-Bou-Arreridj, Msila, Boussaâda. Vol. 5 vol. 5. Arnolet. pp. 208–211. ISBN 978-2-296-54115-3.

- ^ Gaïd, Mouloud (1978). Chroniques des Beys de Constantine. Algiers: Office des publications universitaires. p. 114.

- ^ a b Rinn, Louis (1891). Histoire de l'Insurrection de 1871 en Algerie (PDF). Algiers: Librairie Adolphe Jourdan.

- ^ Ageron, Charles-Robert (1966). "La politique kabyle sous le Second Empire" [Kabyle politics under the Second Empire]. Outre-Mers. Revue d'histoire (in French). 53 (190): 102. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ Murray Steele, 'Algeria: Government and Administration, 1830-1914', Encyclopedia of African History, ed. by Kevin Shillington, 3 vols (New York: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2005), I pp. 50-52 (at p. 51).

- ^ Lorcy, Damien (2011). "Sous le régime du sabre" (PDF). Presses universitaires de Rennes. Retrieved April 30, 2018. p.17

- ^ Le Régime du Sabre en Algerie. Paris: Dentu. 1869. p. 20.

- ^ Rey-Goldzeiguer, Annie (1981). "Le Royaume Arabe. La politique algérienne de Napoléon III, I861-1870" [The Arab Kingdom: the Algerian policy of Napoleon III 1861-1870]. Revue d'Histoire Moderne & Contemporaine (in French). 28 (2): 383. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Bernard Droz, « Insurrection de 1871: la révolte de Mokrani », dans Jeannine Verdès-Leroux (dir.), L'Algérie et la France, Paris, Robert Laffont 2009, p. 474-475 ISBN 978-2-221-10946-5

- ^ a b c d Liorel, Jules (1892). E. Leroux (ed.). Races berbères: Kabylie du Djurdjura. Paris. pp. 247–249.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ayoun, Richard (1988). Presses universitaires de France (ed.). "Le décret Crémieux et l'insurrection de 1871 en Algérie". Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine. 35 (1). Paris: 61–87. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1988.1439.

- ^ Ait Kaki, Maxine (2004). Éditions L'Harmattan (ed.). De la question berbère au dilemme kabyle à l'aube du sXXI. L'Harmattan. ISBN 9782747557283.

- ^ Bertolini, Gilbert (April 13, 2012). "La Commune de Paris et l'Algérie". www.commune1871.org. Commune 1871. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ R. Hure, page 155, L'Armee d'Afrique 1830–1962, Charles-Lavauzelle 1977

- ^ a b Julien, Charles-André (1964). Histoire de l'Algérie contemporaine. Vol. 1. Paris: PUF. pp. 475–476.

- ^ Lettre de Mokrani au Général Augerand, dans le Rapport de M. Léon de La Sicotière au nom de la « Commission d’Enquête sur les actes du Gouvernement de la Défense Nationale », Versailles, Cerf et fils, 1875, p. 768

- ^ a b Jolly, Jean (1996). Histoire du continent africain: de la préhistoire à 1600. Vol. 1. Éditions L'Harmattan. ISBN 9782738446886.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip (2006). Historical Dictionary of Algeria. Scarecrow Press. p. 305. ISBN 9780810864801.

- ^ Wahl, Maurice (1896). La France aux colonies. Paris: Librairies-Imprimeries réunies.

- ^ Bulletin officiel du gouvernement général de l'Algérie. Vol. 11. Algiers: Bouyer. 1872. p. 188.

- ^ Darmon, Pierre (2009). Un siècle de passions algériennes: Histoire de l'Algérie coloniale (1830-1940). Fayard. p. 271. ISBN 9782213653990.

- ^ Montagnon, Pierre (December 15, 2012). La conquête de l'Algérie : Les germes de la discorde. Éditions Flammarion. p. 471. ISBN 9782756408774.

- ^ a b c Moussaoui, Rosa (September 5, 2011). "Cheikh El Mokrani (1815-1871) Le chef de la Commune kabyle, en guerre contre la colonisation (43)". www.humanite.fr. L’Humanité. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ Léon Devambez. "Camp des déportés arabes à la presqu'ile Ducos". Archives nationales d'outremer. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ "Le XIXe siècle : Journal quotidien politique et littéraire / Directeur-rédacteur en chef : Gustave Chadeuil". January 3, 1873.

- ^ "Revue de France / Directeur-gérant Léonce Dumont". April 1875.

- ^ "Les oubliés de l'Histoire coloniale du Pacifique (Mélica Ouennoughi) - études-coloniales". October 12, 2006.

- ^ "Noms des déportés algériens". iisg.nl. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ "New Caledonia" (PDF). IISG. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ "Déportés algériens en Nouvelle-Calédonie - études-coloniales". May 14, 2011.

- ^ "la Loire". Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ "La Revue maritime". 1875.

- ^ Ouennoughi, Mélica (2005). Les déportés maghrébins en Nouvelle-Calédonie et la culture du palmier dattier de 1864 à nos jours. Harmattan. ISBN 9782747596015.

- ^ Kharchi, Djamel (2004). Colonisation et politique d'assimilation en Algérie 1830-1962. Casbah. ISBN 9789961644805.

- ^ Angleviel, Frédéric (2014). Histoire du pays Kunie (L'Île des Pins): De la terre de tous les exils à l'île la plus proche du paradis. Mairie de l'Île des Pins. ISBN 9782953990867.

- ^ Déportés et forçats de la Commune : De Belleville à Nouméa / Roger Pérennès. 1991.

- ^ Pérennès, Roger (1991). Déportés et forçats de la Commune: De Belleville à Nouméa. Ouest éditions. ISBN 9782908261806.

- ^ Mémoires d'un communard : Des barricades au bagne / Jean Allemane. 1906.

- ^ Allemane, Jean (2001). Mémoires d'un communard. La Découverte. ISBN 9782707135261.

- ^ Pisier, Georges (1971). "Les déportés de la Commune à l'île des Pins, 1872-1880".

- ^ Pisier, Georges (1971). "Les déportés de la Commune à l'île des Pins, Nouvelle-Calédonie, 1872-1880". Journal de la Société des Océanistes. 27 (31): 103–140. doi:10.3406/jso.1971.2322.

- ^ Barbançon, Louis-José; Sand, Christophe (2013). Caledoun: Histoire des Arabes et Berbères de Nouvelle-Calédonie. Association des Arabes et Amis des Arabes de Nouvelle-Calédonie. ISBN 9782954167503.

- ^ Barbançon, Louis-José (2003). L' Archipel des forçats: Histoire du bagne de Nouvelle-Calédonie (1863-1931). Presses Univ. Septentrion. ISBN 9782859397852.

- ^ Barbançon, Louis-José (January 1995). La terre du lézard. FeniXX réédition numérique. ISBN 9782307118138.