State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts

State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts are state laws based on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), a federal law that was passed almost unanimously[4][5] by the U.S. Congress in 1993 and signed into law by President Bill Clinton.[6][7] The laws mandate that religious liberty of individuals can only be limited by the "least restrictive means of furthering a compelling government interest".[8] Originally, the federal law was intended to apply to federal, state, and local governments. In 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court in City of Boerne v. Flores held that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act only applies to the federal government but not states and other local municipalities within them. As a result, 21 states have passed their own RFRAs that apply to their individual state and local governments.

Pre Hobby Lobby

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, Pub. L. No. 103-141, 107 Stat. 1488 (November 16, 1993), codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb through 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb-4 (also known as RFRA), is a 1993 United States federal law that "ensures that interests in religious freedom are protected."[9] The bill was introduced by Congressman Chuck Schumer (D-NY) on March 11, 1993. A companion bill was introduced in the Senate by Ted Kennedy (D-MA) the same day. A unanimous U.S. House and a nearly unanimous U.S. Senate—three senators voted against passage[4]—passed the bill, and President Bill Clinton signed it into law.

The federal RFRA was held unconstitutional as applied to the states in the City of Boerne v. Flores decision in 1997, which ruled that the RFRA is not a proper exercise of Congress's enforcement power. However, it continues to be applied to the federal government—for instance, in Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal—because Congress has broad authority to carve out exemptions from federal laws and regulations that it itself has authorized. In response to City of Boerne v. Flores and other related RFRA issues, twenty-one individual states have passed State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts that apply to state governments and local municipalities.[10]

State RFRA laws require the Sherbert Test, which was set forth by Sherbert v. Verner, and Wisconsin v. Yoder, mandating that strict scrutiny be used when determining whether the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, guaranteeing religious freedom, has been violated. In the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which usually serves as a model for state RFRAs, Congress states in its findings that a religiously neutral law can burden a religion just as much as one that was intended to interfere with religion;[11] therefore the act states that the "Government shall not substantially burden a person's exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability."[12]

The federal RFRA provided an exception if two conditions are both met. First, the burden must be necessary for the "furtherance of a compelling government interest".[12] Under strict scrutiny, a government interest is compelling when it is more than routine and does more than simply improve government efficiency. A compelling interest relates directly with core constitutional issues.[13] The second condition is that the rule must be the least restrictive way in which to further the government interest.

Post Hobby Lobby

In 2014, the United States Supreme Court handed down a landmark decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. recognizing a for-profit corporation's claim of religious belief.[3] Nineteen members of Congress who signed the original RFRA stated in a submission to the Supreme Court that they "could not have anticipated, and did not intend, such a broad and unprecedented expansion of RFRA".[14] The United States government stated a similar position in a brief for the case submitted before the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, writing that "Congress could not have anticipated, and did not intend, such a broad and unprecedented expansion of RFRA. ... The test Congress reinstated through RFRA ... extended free-exercise rights only to individuals and to religious, non-profit organizations. No Supreme Court precedent had extended free-exercise rights to secular, for-profit corporations."[15][full citation needed]

Following the Burwell v. Hobby Lobby decision, many states have proposed expanding state RFRA laws to include for-profit corporations,[16][17] including in Arizona where SB 1062 passed by in Arizona but vetoed by Jan Brewer in 2014.[18][19] Indiana SB 101 defines a "person" as "a partnership, a limited liability company, a corporation, a company, a firm, a society, a joint-stock company, an unincorporated association" or another entity driven by religious belief that can sue and be sued, "regardless of whether the entity is organized and operated for profit or nonprofit purposes".[20] Indiana Democrats proposed an amendment that would not permit businesses to discriminate and the amendment was voted down.[21]

An RFRA bill in Georgia has stalled, with constituents expressing concern to Georgia lawmakers about the financial impacts of such a bill.[22][23][24] Stacey Evans proposed an amendment to change references of "persons" to "individuals", which would have eliminated closely held for-profit corporations from the proposed law, but the amendment was rejected because it would not give protections to closely held corporations to practice religious freedoms granted by the Supreme Court in the Hobby Lobby case.[22]

Some commentators believe that the existence of a state-level RFRA bill in Washington could have affected the outcome of the Arlene's Flowers lawsuit.[25][26]

Politifact reports that "Conservatives in Indiana and elsewhere see the Religious Freedom Restoration Act as a vehicle for fighting back against the legalization of same-sex marriage."[27] Despite being of intense interest to religious groups, state RFRAs have never been successfully used to defend discrimination against gays—and have rarely been used at all.[28] The New York Times noted in March 2015 that state RFRAs became so controversial is due to their timing, context and substance following the Hobby Lobby decision.[29]

Several law professors from Indiana stated that State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts like "Indiana SB 101" are in conflict with the U.S. Supreme Court's Free Exercise Clause jurisprudence under that "neither the government nor the law may accommodate religious belief by lifting burdens on religious actors if doing so shifts those burdens to third parties. [...] The Supreme Court has consistently held that the government may not accommodate religious belief by lifting burdens on religious actors if that means shifting meaningful burdens to third parties. This principle protects against the possibility that the government could impose the beliefs of some citizens on other citizens, thereby taking sides in religious disputes among private parties. Avoiding that kind of official bias on questions as charged as religious ones is a core norm of the First Amendment."[30] The Supreme Court for example stated in Estate of Thornton v. Caldor, Inc. (1985): "The First Amendment ... gives no one the right to insist that, in pursuit of their own interests others must conform their conduct to his own religious necessities.'" Relying on that statement they point that the U.S. Constitution allows special exemptions for religious actors, but only when they don't work to impose costs on others. Insisting on "the constitutional importance of avoiding burdenshifting to third parties when considering accommodations for religion" they point out the case of United States v. Lee (1982).[30] Here the court stated:

Congress and the courts have been sensitive to the needs flowing from the Free Exercise Clause, but every person cannot be shielded from all the burdens incident to exercising every aspect of the right to practice religious beliefs. When followers of a particular sect enter into commercial activity as a matter of choice, the limits they accept on their own conduct as a matter of conscience and faith are not to be superimposed on the statutory schemes which are binding on others in that activity. Granting an exemption from social security taxes to an employer operates to impose the employer's religious faith on the employees.[31]

Effects of RFRAs on state court cases

Mandates courts use the following when considering religious liberty cases:

- Strict scrutiny

- Religious liberty can only be limited for a compelling government interest

- If religious liberty is to be limited, it must be done in the least restrictive manner possible

States with RFRAs

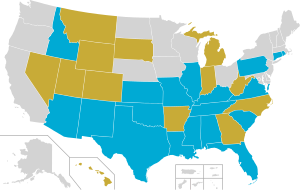

By legislature

Legislatures of 25 states have enacted versions of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act:

- Alabama (state constitution amendment)[32]

- Arizona[33]

- Arkansas[29][34]

- Connecticut[33]

- Florida[33]

- Idaho[33]

- Illinois[33]

- Indiana[35][36][37][38][39][40]

- Kansas[33]

- Kentucky[41]

- Louisiana[33]

- Mississippi[42][43]

- Missouri[33]

- Montana

- New Mexico[33]

- North Dakota

- Oklahoma[33]

- Pennsylvania[33]

- Rhode Island[33]

- South Carolina[33]

- South Dakota [44]

- Tennessee[33]

- Texas[33]

- Virginia[33]

- West Virginia [45]

By state court decision

An additional 9 states have RFRA-like provisions that were provided by state court decisions rather than via legislation:[46][47]

- Alaska

- Hawaii

- Ohio

- Maine

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Washington

- Wisconsin

Reversals

Some states have had legislation withdrawn or vetoed. Arizona's bill SB 1062 was vetoed by Governor Jan Brewer. Bills 1161 and 1171 have been vetoed by a Colorado committee.[48][49][50]

Additional details on specific state laws

Arkansas

In April 2015, the governor of Arkansas, Asa Hutchinson, signed a religious freedom bill into law. The version of the bill he signed was more narrow in scope than the original version, which would have required state and local governments to demonstrate a compelling governmental interest to be able to infringe on someone's religious beliefs.[51]

Georgia

In March 2016, the Georgia State Senate and the Georgia House of Representatives passed a religious freedom bill.[52] On March 28, Georgia's governor, Nathan Deal, vetoed the bill after multiple Hollywood figures, as well as the Walt Disney Company threatened to pull future productions from the state if the bill became law.[53] Many other companies had also been opposed to the bill, including the National Football League, Salesforce, the Coca-Cola Company, and Unilever.[54][55]

Indiana

In March 2015, Gov. Mike Pence signed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, allowing business owners who object to same-sex couples on religious grounds to opt out of providing them services.[56]

Mississippi

In April 2016, Phil Bryant, the governor of Mississippi, signed into law a bill that protects people from government punishment if they refuse to serve others on the basis of their own religious objection to same-sex marriage, transgender people, or extramarital sex.[57] The sponsors of "Project Blitz," a coalition of conservative Christian organizations supporting dozens of "religious liberty" bills at the state level across the United States, see Mississippi's law as model legislation.[58]

Missouri

On March 9, 2016, the Missouri State Senate passed a religious freedom bill. Senate Democrats tried to stop the bill with a 39-hour filibuster, but Republicans responded by forcing a vote using a rarely used procedural maneuver, which resulted in the bill passing.[59] In April, it was defeated 6-6 in a Missouri House of Representatives committee vote, with three Republicans joining three Democrats in voting against the bill.[60]

South Dakota

On March 10, 2017, Dennis Daugaard, the governor of South Dakota, signed into law SB 149, which allows taxpayer-funded adoption agencies to deny services under circumstances that conflict with religious beliefs.[61]

Texas

On May 20, 2019, the Texas House passed a version of Senate Bill 1978 which prohibits the government from penalizing anyone for “membership in, affiliation with, or contribution...to a religious organization.” The bill was expected to pass the Senate again rapidly and to be signed by the governor.[62] On June 10, 2019 the governor signed the bill officially into law and it took effect immediately.[63] Some have called it the "Save Chick-fil-A" law, given that the fast-food chain Chick-fil-A has been criticized for its donations to anti-LGBT causes.[64]

References

- ^ "State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts". National Conference of State Legislatures. March 30, 2015.

- ^ "2015 State Religious Freedom Restoration Legislation". National Conference of State Legislatures. 30 Mar 2015.

- ^ a b "NCAA 'concerned' over Indiana law that allows biz to reject gays". CNN. 26 March 2015.

social conservatives have been re-energized in their push for "religious freedom" laws after the Supreme Court's decision in a health care-related case that allowed Hobby Lobby and other businesses to opt not to provide insurance coverage for contraception.

- ^ a b "1A. What Is the Religious Freedom Restoration Act?". The Volokh Conspiracy. 2 December 2013.

- ^ "Indiana's Religious Freedom Restoration Act, Explained | The Weekly Standard". Archived from the original on 2015-03-28.

- ^ "Full Text of the Religious Freedom Restoraction Act". religiousfreedom.lib.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on 25 May 2001. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "1A. What Is the Religious Freedom Restoration Act?". The Volokh Conspiracy. 2 December 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Apple's Tim Cook 'deeply disappointed' in Indiana's anti-gay law". CNN Money. 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (slip opinion), Concurring opinion by judge Anthony Kennedy at page 1 of that concurring opinion respectively page 56 of 95 of the slip opinion in general" (PDF). United States Supreme Court. June 30, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "State Religious Freedom Acts". National Conference of State Legislatures. May 5, 2017. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020.

- ^ Religious Freedom Restoration Act full text at http://www.prop1.org/rainbow/rfra.htm

- ^ a b Utter, Jack (2001). American Indians: Answers to Today's Questions. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 159. ISBN 0-8061-3309-0.

- ^ Ross, Susan (2004). Deciding communication law: key cases in context. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-4698-0.[page needed]

- ^ Katherine Franke, Kara Loewentheil, Jennifer Drobac, Rob Katz, Fran Quigley, Florence Wagman Roisman, Lea Shaver, Deborah Widiss , Susan H. Williams, Carwina Weng, Jeannine Bell, Aviva Orenstein, Shawn Marie Boyne, Jeffrey O. Cooper, Ira C. Lupu, Nelson Tebbe, Robert W. Tuttle, Ariela Gross, Naomi Mezey, Caroline Mala Corbin, Richard C. Schragger, Micah J. Schwartzman, Steven K. Green, Nomi Stolzenberg, Sarah Barringer Gordon, Frederick Mark Gedicks, Claudia E. Haupt, Marci A. Hamilton, Laura S. Underkuffl and Carlos A. Ball (February 27, 2015). "Letter to Representative Ed DeLaney (Indiana House of Representatives)" (PDF). Columbia University in the City of New York. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

Nineteen members of Congress who voted for the passage of the law in 1993 have now withdrawn their support for the federal RFRA given that it has been interpreted by the courts in ways that were not intended by the Congress at the time of the law's passage. See Brief For United States Senators Murray, Baucus, Boxer, Brown, Cantwell, Cardin, Durbin, Feinstein, Harkin, Johnson, Leahy, Levin, Markey, Menendez, Mikulski, Reid, Sanders, Schumer, And Wyden As Amici Curiae In Support Of Hobby Lobby Petitioners And Conestoga Respondents, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Inc., 134. U.S. 2751 (2014) ('[We] could not have anticipated, and did not intend, such a broad and unprecedented expansion of RFRA.').

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mott, Ronni. "Hobby Lobby Wages War on Birth Control". The Jackson Free Press.

- ^ Michaelson, Jay (16 Nov 2014). "RFRA Madness: What's Next for Anti-Democratic 'Religious Exemptions'". The Daily Beast.

- ^ How Hobby Lobby paved the way for Indiana's 'religious freedom' bill (27 Mar 2015). "How Hobby Lobby paved the way for Indiana's 'religious freedom' bill". Washington Post.

- ^ Catherine E. Shoichet (27 Feb 2015). "Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer vetoes controversial bill, SB 1062". CNN.

- ^ "Arizona gov. vetoes controversial 'religious freedom' bill". Aljazeera. 26 Feb 2015.

- ^ "Did Barack Obama vote for Religious Freedom Restoration Act with 'very same' wording as Indiana's?". Politifact. 29 Mar 2015.

- ^ "What Makes Indiana's Religious-Freedom Law Different?". The Atlantic. 30 Mar 2015.

- ^ a b "'Religious liberty' bill takes a sharp rightward turn, convention industry says $15 million in business at risk". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (blog). 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Georgia House Committee Tables 'Religious Liberty' Bill". 90.1 FM WABE. 26 Mar 2015.

- ^ "LGBT rights amendment proves to be 'poison pill' for Georgia's 'religious freedom' bill". Raw Story. 27 Mar 2015.

- ^ Burk, Denny (20 February 2015). "The Christian conscience of Barronelle Stutzman". CNN.

- ^ "Analysis Indiana Religious Freedom Law is not Anti-Gay". Christian Post. 27 Mar 2015.

- ^ Lauren Carroll, Katie Sanders, Aaron Sharockman (March 29, 2015). "Fact-checking the March 29 news shows". Politifact. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rachel Zoll and David Crary (March 31, 2015). "Religious freedom laws not used against gays in the past". The Associated Press. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Context for the Debate on 'Religious Freedom' Measures in Indiana and Arkansas". The New York Times. March 31, 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ a b Katherine Franke, Kara Loewentheil, Jennifer Drobac, Rob Katz, Fran Quigley, Florence Wagman Roisman, Lea Shaver, Deborah Widiss , Susan H. Williams, Carwina Weng, Jeannine Bell, Aviva Orenstein, Shawn Marie Boyne, Jeffrey O. Cooper, Ira C. Lupu, Nelson Tebbe, Robert W. Tuttle, Ariela Gross, Naomi Mezey, Caroline Mala Corbin, Richard C. Schragger, Micah J. Schwartzman, Steven K. Green, Nomi Stolzenberg, Sarah Barringer Gordon, Frederick Mark Gedicks, Claudia E. Haupt, Marci A. Hamilton, Laura S. Underkuffl and Carlos A. Ball (February 27, 2015). "Letter to Representative Ed DeLaney (Indiana House of Representatives)" (PDF). Columbia University in the City of New York. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ United States v. Lee (1982)|United States v. Lee, 455 U.S. 252 (1982)

- ^ "State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts". www.churchstatelaw.com. Lewis Roca Rothgerber Religious Institutions Group. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "State Religious Freedom Restoration Acts". National Conference of State Legislatures. July 6, 2015. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ Campbell Robertson and Richard Péres-Pena (March 31, 2015). "Bills on 'Religious Freedom' Upset Capitols in Arkansas and Indiana". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ Cook, Tony (April 2, 2015). "Gov. Mike Pence signs 'religious freedom' bill in private". The Indy Star. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Gov. Mike Pence signs 'religious freedom' bill in private". indystar.com. Indy Star. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Here it is: The text of Indiana's 'religious freedom' law". The Indy Star. April 2, 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Tony Cook, Tom LoBianco and Brian Eason (April 2, 2015). "Gov. Mike Pence signs RFRA fix". The Indy Star. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Read the text of proposed RFRA changes". The Indy Star. April 2, 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "Conference Committee Report Digest for ESB 50; Citations Affected. IC 34-13-9". documentcloud.org. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "HB279 13RS". www.lrc.ky.gov. Kentucky Legislative Research Commission. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Rogers, Alex (April 4, 2015). "Mississippi Governor Signs Controversial Religious Freedom Bill". Time Magazine. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "The Mississippi Religious Freedom Restoration Act (Senate Bill No. 2681)" (PDF). billstatus.ls.state.ms.us. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ "An Act to provide protections for the exercise of religious freedom". South Dakota Legislature. March 10, 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Template:Https://apnews.com/article/lgbtq-discrimination-religious-freedom-west-virginia-1301d525c95eb4b826dd38c05f62b65b

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet (March 1, 2014). "31 states have heightened religious freedom protections". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Eugene Volokh (December 2, 2013). "1A. What Is the Religious Freedom Restoration Act?". The Volokh Conspiracy. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Moreno, Ivan (March 9, 2015). "Lawmakers wrestle with religious rights and nondiscrimination laws". The Washington Times. The Associated Press. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Schrader, Megan (March 10, 2015). "Klingenschmitt bill to amend Colorado anti-discrimination bill shot down". The Gazette. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Hope Errico Wisneski (March 10, 2014). "Colorado Victory: Discriminatory Legislation Does Not Progress in Legislature". The Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Trager, Kevin (2 April 2015). "Arkansas governor signs new 'religious freedom' bill". USA Today. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Botehlo, Greg (17 March 2016). "Ga. governor cites Jesus in signaling 'religious freedom' bill opposition". CNN. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Somashekhar, Sandhya (28 March 2016). "Georgia governor vetoes religious freedom bill criticized as anti-gay". Washington Post. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ "Governor of Georgia vetoes religious freedom bill". BBC News. 28 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (25 March 2016). "Georgia's 'anti-LGBT' bill: These companies are speaking out the loudest". CNN. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Neuman, Scott (26 March 2015). "Indiana's Governor Signs 'Religious Freedom' Bill". NPR. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Domonoske, Camila (5 April 2016). "Mississippi Governor Signs 'Religious Freedom' Bill Into Law". NPR. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ^ Stewart, Katherine (26 May 2018). "A Christian Nationalist Blitz". New York Times. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ Botehlo, Greg (9 March 2016). "Missouri 'religious freedom bill' passes as 39-hour filibuster ends". CNN. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Farrington, Dara (27 April 2016). "Missouri 'Religious Freedom' Bill Defeated In House Committee Vote". NPR. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Chris (10 March 2017). "South Dakota governor signs first anti-LGBT law of 2017". Washington Blade. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Platoff, Emma (2019-05-20). "Texas House passes religious liberty bill amid LGBTQ Caucus' objections". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^ "Texas SB1978 | 2019-2020 | 86th Legislature".

- ^ Bollinger, Alex (2019-05-21). "Texas is about to get a 'Save Chick-fil-A' law that legalizes anti-LGBTQ discrimination". lgbtqnation.com. Retrieved 2019-05-22.